Introduction

The traditional meaning of interprofessional education (IPE) is when students from two or more professions learn from each other about how to collaborate more effectively and, ultimately, achieve better health outcomes when working together as health care professionals.1 IPE focuses not only on interprofessional education but also interprofessional practice and collaborative practice. The National Center for Interprofessional Education and Practice (NCIEP) envisions a “new IPE” that incorporates these concepts to create stronger support systems and models of practice. The new IPE aims to bring interprofessional education out of the classroom and into the practice setting, promoting collaboration among health care professionals and workers across multiple training areas to improve health outcomes and reduce costs.2

This type of broad-based education does come at a cost. One-off IPE educational experiences can be entertaining and informative, but they will not weave IPE into the fabric of future care. Some universities are investing hundreds of thousands of dollars in this type of education, hiring directors and associate deans to oversee IPE implementation and investing in costly simulations and programs. Other universities are still just dipping their toes into IPE and trying to determine the most cost-effective way to initiate programs. After all, academia itself is not set up for collaboration across programs, departments, and colleges. Courses are typically established for one class in one academic program, and while they can be opened to other programs pending class size, try adding a faculty member from another discipline. Faculty loads and reimbursement place a quick and firm chokehold on such efforts. Successful implementation of IPE requires work to be done in ways that are outside the constructs of the traditional academic environment.

When Should IPE Begin?

Successful interprofessional teams have shared goals, clearly defined roles, and effective communication skills.3 IPE and collaboration are essential to enhancing patient safety and delivering high-quality care.4,5 Few would argue against the notion that IPE and collaboration should be intentional elements in health care curricula to prepare students for future roles on multidisciplinary teams.5–7 But when should IPE begin? If universities are going to invest time, money, and resources in IPE, should it take place during classes? Internships? Or does it make more sense to have students just finish their coursework during their degree programs and save IPE for when they are working every day with other health professionals? It is important to demonstrate that IPE can succeed in academia and define the processes that can lead to its success.

The evidence shows many benefits for students who engage in IPE activities during their education, such as developing a deeper awareness of other professions’ roles, skills, and values.5,8 Several studies have found that students participating in IPE report increased confidence, improved attitudes toward teamwork, and enhanced communication skills.5,9 Providing health care professions students with IPE experiences while they are in academic training programs may encourage future positive interprofessional collaborations. A recent systematic review indicated improved attitudes and perceptions toward students and professionals of other disciplines, the value of a team-based approach with the implementation of IPE, and positive changes in collaborative behavior.10 Findings were mixed but positive for improving knowledge of roles and responsibilities of other professionals, with noted needs for improved quality of data collection on pertinent outcome measures. Results also showed trends toward improved collaborative skills.10 What is most lacking at the moment is evidence demonstrating an impact on the practice of professionals. While some studies report certain elements of improved care, their scientific rigor has been critiqued, and there are not enough studies reporting such outcomes.

How is IPE Implemented with Students?

Activities should focus on one or more of the four core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice11: values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, communication, and teams and teamwork.12 IPE can be a required part of coursework or elective activities and occurs in various educational settings: classrooms or other meeting spaces, online learning platforms, laboratories, and clinical sites. Choice of format and environment depends on desired learning objectives, the academic level of the involved students, mode of program delivery, student schedule restrictions, and availability of resources. Early and repeated exposure to IPE is important.13 After building requisite understanding of the core competencies, faculty should guide students to apply knowledge and skills during experiential IPE activities.

IPE is often initiated in classrooms. This can be as simple as inviting guest speakers to classes with students from different disciplines. Students are eager to hear these “real-life” stories and have the opportunity to ask questions and engage in robust discussion. Case studies can also be presented to allow students to learn how to address clinical problems through an interprofessional lens. These “hands-on” activities actively engage students and can easily be implemented in classrooms of multiple disciplines. However, space limitations can deter inviting other students to join single-discipline classes. This barrier can be addressed by using teleconferencing, as UNC-Greensboro and High Point University do to enable nursing and pharmacy students to collaboratively learn about environmental health. Another strategy is to group students from multiple classes together to complete an activity outside of class, bringing their group’s work back for discussion in their own classrooms.

Online learning platforms are increasingly being used for IPE.14 Campbell University faculty present a patient case to interprofessional student teams with discussion questions about roles/responsibilities and communication strategies. UNC-Charlotte hosts a 15-week online IPE course that builds understanding of all four core competencies in initial modules, and then student teams apply that knowledge to plan patient, family, and community care.15 Online IPE can address space and scheduling barriers, involve distance learners, and offer continuity during unforeseen circumstances like COVID-19 campus restrictions.16 Yet, virtual events can have challenges such as difficulty engaging students, particularly if they do not turn on their video cameras.17 Another option is to have hybrid IPE events where students meet in person but utilize a single laptop for their team to connect to an online activity, such as a poverty simulation. This can aid faculty in managing many students while simultaneously providing an in-person IPE experience. IPE escape room experiences have recently begun to emerge,18 though they currently require in-house design and development.

In-person laboratory and simulation activities can also be highly effective. One example is with practicing health and psychomotor skill assessments,19 many of which are used across professions. An IPE event at Wingate University involves fundamental skills selected by faculty from various disciplines. Students may learn how a physician assistant would conduct an HEENT examination (head, eyes, ears, nose, throat), how a physical therapist would perform muscle and sensory testing, how an occupational therapist would use an assistive device, and how a pharmacist would determine if a prescription contains legally required components. Simulations provide experiential IPE as students collaborate to care for high-fidelity manikins or actors known as standardized patients (SPs), and debriefings aid them in connecting the experience to future practice situations.20 Nursing and social work students at UNC-Charlotte complete a simulation on caring for older adults in community settings. In a mock home residence, student teams complete an escape room by identifying fall risk, food insecurity, and polypharmacy concerns. There is a telehealth encounter to meet the patient (an SP) and screen for social determinants of health. The experience concludes in a clinic room where students present their plan to the SP, providing education and resources.21 Technology-enhanced simulations are growing in popularity. At UNC-Greensboro, an online simulation on end-of-life care uses multiple short recorded videos, and students and faculty discuss key learning points and share personal experiences as the story progresses. Virtual reality (VR) simulations utilize headsets to immerse students in realistic, interactive environments.22 Appalachian State University faculty utilize VR to allow students from various disciplines to experience dementia firsthand and share experiences. Simulation technology is innovative and effective, yet costly.

Learning in clinical settings is also a vital component of health professions education, preparing students for practice.23 Clinical environments provide exposure to the interprofessional team and enable students to learn about different roles via observation and interaction. Faculty can facilitate in-depth understanding of other disciplines by having students interview or shadow an individual from another profession. With meaningful reflection, these experiences improve appreciation, confidence, and skills for collaborative practice.24 The Appalachian Institute for Health and Wellness at Appalachian State University has an interprofessional clinic that facilitates this process internally. Student-led clinics are increasingly being recognized as an ideal venue for IPE. Another approach is community-based learning. Medicine, pharmacy, nursing, social work, and health psychology students from multiple Charlotte-area universities elected to participate in interprofessional student hot-spotting. For six months, student teams worked with individuals in the community with complex health needs to reduce emergency room visits and costs.25 This approach can increase clinical IPE participation because, unlike IPE efforts in hospital settings, the number of students present does not need to be limited.

A single activity or sporadic IPE experiences are unlikely to result in practice readiness. It is important for IPE to be threaded through curricula, with careful planning to promote stepwise growth, competency attainment, and practice-ready graduates.13

Creating a Framework for Success

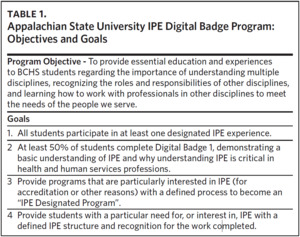

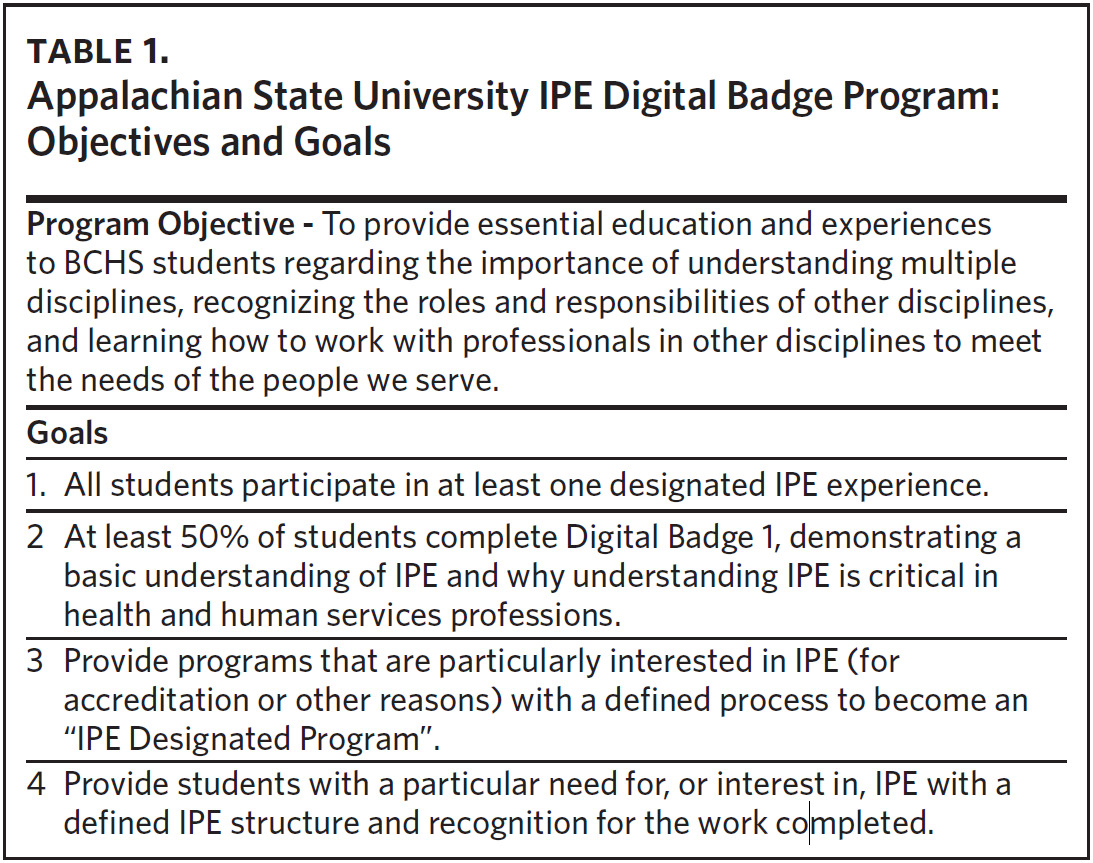

This article has highlighted various types of IPE activities and provided implementation examples. The next step is pulling such activities together in a framework that provides clear benefits to students and programs. Appalachian State’s Beaver College of Health Sciences created an IPE Digital Badge program that addresses student and program needs (Table 1).

The Digital Badge program was designed to guide the student and faculty through the IPE process and provide a place to collect data, including grades and surveys. It is administered through AsULearn, the university’s Moodle-based online teaching/learning platform. An IPE calendar is provided through the university’s Google-based calendar system that is populated by faculty/staff initiating IPE experiences. The calendar is shared college-wide and allows students to gather additional information and sign up for experiences. It is also tied to the IPE website in the student section of the college’s main webpage. The IPE Digital Badge program is in the process of becoming an official micro-credential at Appalachian State that can be added to LinkedIn and other sites, and program facilitators are working toward adding it to official transcripts. All of this provides additional incentives for student participation.

IPE Designated Programs

Accreditation bodies now require many programs to demonstrate IPE within their curricula. This was the impetus for Appalachian State’s new IPE Designated Programs. This designation provides concrete evidence to accreditation bodies that programs meet this accreditation standard. For programs to become IPE Designated Programs, they must comply with the following:

-

100% of students complete Digital Badge 1

-

50% of students complete Digital Badge 2

-

50% of faculty participate in the provision of IPE programming

-

The Program Director works to collect IPE requirements and reporting through AsULearn and charts student progress (for Digital Badges 2 and 3)

The early response is positive, and several programs— all with accreditation bodies that require IPE—are working toward this designation. The incentives for the programs are clear, and both administrators and students understand and support it.

The Future of IPE in Universities

IPE is clearly valued as part of early and ongoing education for future and current health care providers. Evidence is beginning to emerge in support of what experts on the matter have been espousing for some time. However, more evidence is needed. Pre- and post-event surveys don’t capture the level of data necessary to demonstrate that care of patients improves over time with IPE. Such studies should be conducted with the same level of rigor expected of any clinical assessment or intervention for patients.

In addition, universities should be sharing their methodologies and learning from one another. IPE is not a competition. If, in fact, it can actually improve patient care and health outcomes, then it is imperative that students receive effective IPE beginning at the right time and have it as part of their continuing education. Providing IPE across disciplines is challenging for universities, clinics, and hospitals because it can be costly and is not reimbursable through tuition or medical billing. Thus, rigorously demonstrating and sharing what works are equally important. In collaboration with North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (NC AHEC), faculty and practitioners across North Carolina are doing this well, holding quarterly IPE meetings and sharing information in various formats, including this issue of NCMJ. IPE is all about communication and collaboration, so it is not surprising that abiding by these principles ourselves will lead to better outcomes for all.

Acknowledgments

All authors report no conflicts of interest.