Introduction

Since 2021, North Carolina’s population has grown at the 5th-highest rate of any state in the United States, to nearly 11 million.1 Birth rates have resumed pre-pandemic levels, and overall the population has continued to age, with an influx of older retirees to the state.1 The increasing size of the state’s population has important implications for those working in health care and public health. “Healthy North Carolina 2030” identifies a range of public health goals addressing economic, environmental, and social drivers of health.2 To care for the growing population, we must shift our understanding of the health care workforce to include an array of professions working together in different settings and communities. Additionally, growth in Affordable Care Act health insurance enrollments and Medicaid expansion in North Carolina will reduce barriers to accessing and providing the care that state residents need and deserve. Anticipating this need, experts have challenged leaders to build a health workforce that “enhances availability, accessibility, acceptability, accommodation, and affordability of care”.3

Unfortunately, health workforce shortages are pervasive across the state, particularly in the most rural and underserved areas. A 2018 report in this journal documented such shortages and their adverse impact on team-based care, health access, and outcomes across the state.4 A recent report from the Caregiving Workforce Strategic Leadership Council identifies critical shortages in nursing, mental health, and the direct care workforce.5 In addition, strengthening the capacity of the public health workforce (PHW) to collect local and statewide data and carry out key health initiatives like Healthy North Carolina 2030 is vital. A plan for creating a more “robust and resilient” workforce is being led by a coalition of partners representing government, academic, clinical, and community organizations.6

The North Carolina Center on the Workforce for Health aims to address the numerous challenges of recruiting, training, and retaining the workforce. This vision has three main parts: 1) identifying pathways that promote health professions careers; 2) providing training that aligns with current trends, including interprofessional collaboration, social and mental health services, and emerging technologies; and 3) developing innovative ways to improve job satisfaction and retention by focusing on compensation, on-the-job support, and well-being.6 While not an exhaustive review, this paper begins by explaining the work being done statewide to understand the needs of the current workforce and the areas that require critical attention. We then describe key strategies in pathways, training, and retention efforts and highlight several examples of current programs across the state.

Interprofessional Education Pathways

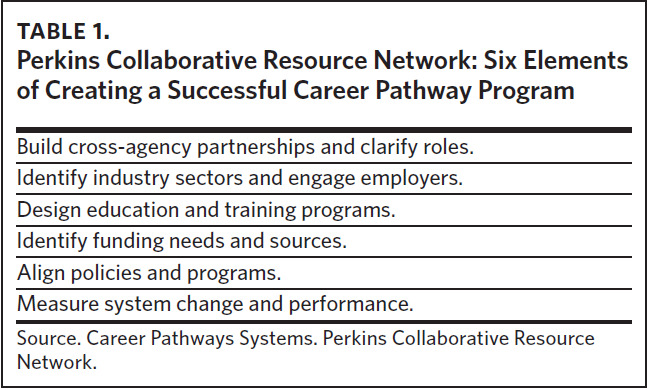

Career pathway programs are designed to prepare students for successful career progression. These programs seek to engage students in educational opportunities in targeted geographical locations to develop the workforce. With the demand for health care workers steadily increasing, pathway programs help connect students to basic education, occupational training, post-secondary education, career and academic advising, and supportive services to assist with preparation and career progression (Table 1).

They have also been shown to increase employment and earnings more than traditional workforce development programs. Importantly, pathway programs are not a quick fix but a long-term strategy, starting as early as elementary school, to encourage students to engage in education for careers in high demand.

Several successful pathway programs exist in North Carolina. One such pathway is the Career and College Promise Associate Degree Nursing Pathway. This allows high school juniors and seniors interested in nursing to begin their educational journey toward an associate or baccalaureate degree in this field. NC Career Launch programs increase post-secondary credential attainment and connect high school students to high-demand jobs.7 Its health care pathways include pre-nursing youth apprenticeships and health care professional youth apprenticeships. These programs provide a combination of classroom and on-the-job education. Tuition waivers and a progressive wage scale create a path to health care careers with financial support and incentives. Several early and middle colleges in North Carolina—public high schools typically located on community college campuses that provide opportunity for high school students to earn college credits—focus on developing the health care workforce and providing entry-level health care credentials by completion, allowing students to work in health care while pursuing more advanced training.7 Another example of interdisciplinary pathways is the Future Clinician Leaders College. This collaboration between the North Carolina Medical Society, Kanof Institute for Physician Leadership, and North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (NC AHEC) seeks to develop leaders in an interprofessional health care environment.8

Additional pathways to health careers are available to high school students through a collaboration between the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction and the North Carolina Community College System. These include programs resulting in certification as an emergency medical technician (EMT) or nurse aide at graduation. Health career programs promote careers within communities across the state, emphasizing engagement with students from those local areas. Additional programs aim to promote careers in health professions among underserved or marginalized high school students. Examples include the Medical Careers and Technology Pipeline (MedCAT) program at Wake Forest University, the Rural Medicine Pathway for Carolina Covenant Scholars at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), and the Building Opportunities and Overtures in Science and Technology (BOOST) program at Duke University.9

Training

Zerden and colleagues suggest multisectoral strategies for training, identifying three leverage points in a health professional’s career trajectory: 1) curricula for people currently enrolled in professional training programs, 2) retooling the current workforce, and 3) an intentional focus on existing team-based care efforts that need strengthening.4 We will focus on leadership, equity, and “emerging needs” training for interprofessional health care and public health teams. These areas align with state and local data findings on PHW and health care professionals’ training needs.10,11

Leadership

Leadership training is paramount for health care professionals, particularly those working in interprofessional teams. The Relational Leadership Institute (RLI) provides fundamental training for successful interprofessional practice that can influence individuals, teams, and systems by enhancing self-awareness, active listening, and engaging with others.12 Duke University offers the Advanced Practice Provider Leadership Institute (APPLI) to support certified nurse midwives, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physical therapists. In this program, graduates work in groups to develop projects that improve patients’ health, increase system efficiency, and educate health professionals.13 APPLI fellows from across the country have gone on to leadership roles within their respective institutions post-completion.

Equity

Equity and inclusivity must be embedded into public health and other health care professionals’ education, training, and work. To provide the best possible care to individuals and populations, it is crucial to recognize and address the root structural causes of inequalities leading to health disparities in our state. This involves assembling health care teams aware of these disparities and inequities and training them in inclusive practices and language. The Racial Equity Institute Groundwater training examines how racism permeates through all levels of our society and is based on three key observations: 1) racial inequity looks the same across systems, 2) socioeconomic difference does not explain the racial inequity, and 3) inequities are caused by systems, regardless of people’s culture or behavior.14 This training is recommended for public health and health care professionals and students at all levels. The Safe Zone Project provides free online education and training on sexuality, gender, and LGBTQI+ topics essential to providing inclusive and equitable care. Trainings are available online and have been developed for learners, professionals, and the public.15

Emerging Issues

Regular training updates are essential to meeting the needs of the current workforce. Nurses entering public health face challenges and high attrition rates due to insufficient public health exposure during their nursing education. Transitioning to competency-based education is essential to building a practice-ready workforce.10 To address this need, the NCDHHS Office of the Chief Public Health Nurse collaborated with the North Carolina Institute of Public Health and public health nurse experts nationwide to create a course on evidence-based fundamental public health and public health nursing information. The North Carolina Credentialed Public Health Nurse course sets a national standard for professional competency-based education.10 The course requires individuals to complete a five-module interprofessional-focused Introduction to Public Health in North Carolina online training as a prerequisite.

Retention

A strong and supported workforce is vital for sustainable and effective health care and public health systems. The National Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PHWINS) in 2019 reported that almost 30% of supervisors and managers expressed their intention to retire or leave their organization in the next five years.16 This aligns with North Carolina’s PHW data and poses a critical challenge for recruiting and retaining new professionals.17 Several factors contribute to increased workforce attrition, including the fact that health care and public health workers nationwide are experiencing stress-related symptoms due to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in many leaving their jobs. Programs that address burnout and emphasize the well-being of our workforce increase job satisfaction and promote retention. Additionally, satisfaction and effective performance require maintaining competency to function effectively in one’s specific area of expertise.4,18 Mentorship is a promising strategy with which to approach this challenge while promoting belonging and well-being among health professionals. Mentoring can empower individuals, increase job satisfaction, and foster career development for the current and future workforce.19,20 Finally, efforts to improve working conditions may be futile without improvements in compensation, especially for frontline and community care providers. Employer- and government-based strategies for improving pay and benefits are essential to retention.5,21

Well-being

Surveys indicate health care workers are experiencing clinically and functionally significant symptoms of stress, anxiety, frustration, intolerance, sadness, anger, fear, grief, and impaired sleep and appetite.22 As such, the workforce has not recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic and is leaving in record numbers. In a 2023 AMN Healthcare Survey of Registered Nurses, 30% of the 18,000 RNs surveyed indicated they would likely leave the profession due to the pandemic and its sequelae.22 At Duke University, with funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration, teams have focused on a two-fold program to support mental health and well-being among health professionals. The Well-B program provides seminars on brief, evidence-based strategies for promoting mindfulness and well-being among health care workers; studies of similar strategies have shown significant decreases in symptoms of burnout and increased happiness.23 In parallel, the Stress First Aid Program has offered clinicians, staff, and students at Duke and North Carolina Central University training in a three-phased approach to assessing stress and supporting coworkers and fellow students.24

Mentorship

North Carolina is home to a strong and thriving higher education system that includes some of the country’s best schools and colleges of medicine, nursing, public health, and other health professions.25 Students are introduced to health and health care from an early age, which helps to create a strong pipeline for recruiting health care professionals.26 Many enrolled in universities and community colleges are first-generation college students. The UNC Network offers mentorship programs that support first-generation students navigating their college experience; UNC Pembroke’s Health Sciences and Innovation Center and UNC Wilmington’s Center for Workforce Development provide mentorship to students pursuing careers in social work, health care, public health, and clinical research.27,28 Diversity in health care and the PHW is essential for representation of the populations we serve in North Carolina. A diverse workforce is one of the greatest assets to an organization and leads to improved morale and retention. The Diverse Healthcare Leaders Program, created by the North Carolina Healthcare Association, aims to promote diversity in health care leadership in NC by connecting high-achieving professionals from underrepresented communities with experienced health care leaders.29

Mentorship programs that support health care and public health professionals to grow into leadership roles are essential in strengthening the workforce. In 2022, a committee of directors of nursing (DON) from local health departments across the state formed to develop a DON mentorship program that enhances skills, knowledge, and relationships. The Meaningful Mentorship program, which provides support, coaching, and connection opportunities, is based on the 2021 Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals and related competency self-assessment tool developed by the Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice.30 A well-designed mentorship program provides support, instills commitment, and can result in improved retention among health care workers.31 While this program was designed to support new DONs, it could easily be adapted to meet the mentorship needs of a wide range of public health and health care professionals.

Financial Incentives and Loan Repayment

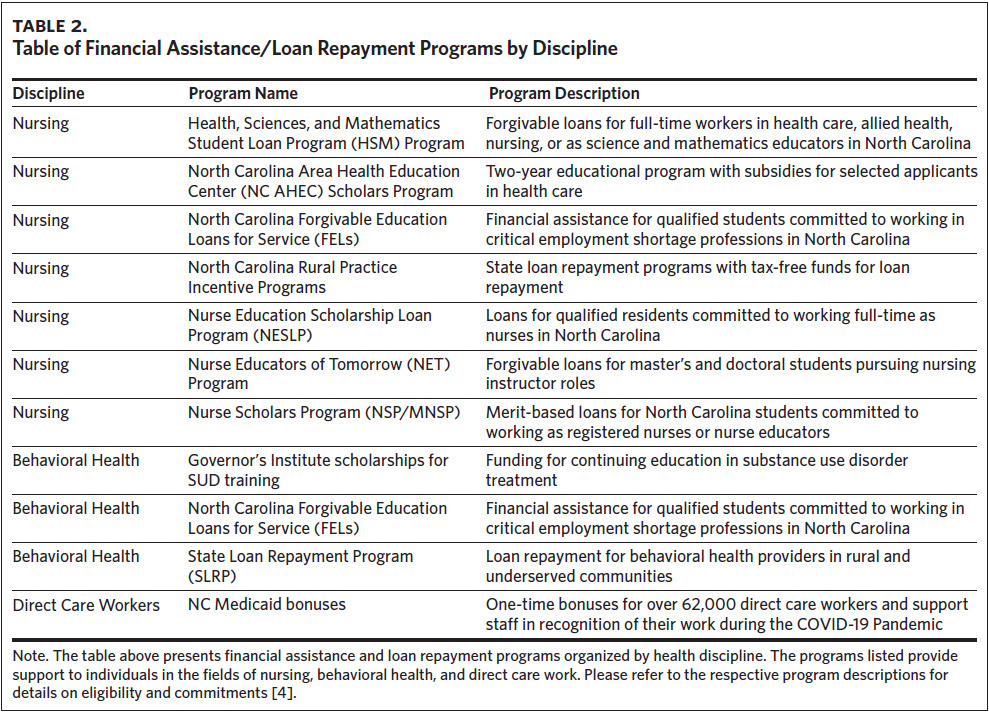

The demand for health care has not been matched by an increase in compensation, particularly for most frontline workers. Turnover is especially high among the direct care workforce after the pandemic, as average pay for these workers in North Carolina is below a living wage. Since the work is often difficult and sometimes dangerous, several programs offer support through tuition benefits, merit bonuses, or loan repayment (Table 2). The January 2024 NCDHHS report on the caregiving workforce advocates for wage increases sponsored by employers and government agencies alongside improvements in working conditions.5

Closing

Developing a public health and health care workforce that can function well in team-based settings is essential to achieving optimal health outcomes for individuals and populations and attaining health equity in our state. This requires creating career pathways that offer early exposure and equal access to all professions, as well as understanding the current capabilities and needs to effectively train the public health and health care workforce. Critical areas that require attention include nurses, behavioral health professionals, and direct care workers, all vital interprofessional team members. Without effective incentive and retention programs, we risk losing skilled and experienced individuals and the valuable institutional knowledge they possess. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize and invest in programs that will create a strong and satisfied public health and health care workforce for our state.

Acknowledgments

Mitch Heflin is a collaborator on the B-Well Essentials program at Duke University funded in part by a cooperative agreement with the Health Resources and Services Administration (163NHP45396-01-00). Jaimee Watts Isley is a Relational Leadership facilitator, a paid per diem role. Maria Turnley is connected to the Meaningful Mentorship program mentioned in the retention section as the creator and ongoing facilitator. No further interests were disclosed.