Drug overdoses throughout the United States have increased at such a staggering rate over the past 20 years that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labeled this issue an epidemic.1 With more than 700,000 confirmed fatal US adult and pediatric drug overdoses between 1999 and 2017, and more than 70,000 fatalities in 2017 alone,2 much research has been dedicated to understanding the factors contributing to both misuse and death.1

While data on substance misuse among adults in the United States are prevalent, pediatric data on substance misuse are less readily available, especially beyond data related to marijuana and alcohol abuse. The vast majority of medical overdoses in children younger than age 5 (95%) involved unintentional exposures.3 An additional 5% were due to errors from adults administering medication to children. Changes in pediatric consumption over the past decade have occurred as young Americans are exposed to recreational drugs at earlier ages, experience increased stressors, and show a trend of increased self-medication without physician consultation.4

In 2017, North Carolina had the 10th-highest total number of drug overdose deaths nationwide.5 North Carolina utilizes a multitude of sources to identify, track, and respond to trends in substance misuse and overdose; this includes Continuum, a North Carolina Office of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) data set utilizing the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) patient care elements, death records from North Carolina Vital Records, the North Carolina Opioid Data Dashboard, and Injury and Violence Prevention Branch poisoning data. Though emergency departments and hospitals provide a wealth of medical data on substance misuse among patients, EMS personnel are often the first, and sometimes the only, clinicians to interact with these patients.6 EMS personnel treat medication and substance use calls using a multitude of techniques, depending on the drug used. A recent study of North Carolina adults in Wake County found as many as one-third of overdose decedents were treated by EMS in the year preceding their death, suggesting prehospital encounters are a good opportunity to intervene prior to an overdose death.

The purpose of this study is to quantify and characterize substance misuse in the North Carolina pediatric (aged < 16 years) population receiving EMS care in 2016. This study will allow for improved and focused EMS and public health and policy initiatives.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of pediatric substance use-related EMS patient encounters in North Carolina during 2016. North Carolina EMS agencies are required to document and report each patient encounter in Continuum within 24 hours. Continuum is a NEMSIS-compliant statewide EMS database mandated by the North Carolina Office of EMS.7 NEMSIS is a national storehouse for EMS data that was developed to standardize the collection, sharing, storage, and analysis of EMS encounters.8 Variables collected from the data set include patient demographics, chief complaints, symptoms, and alcohol or drug usage, among others. The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina reviewed and approved this study.

Study Setting and Population

Subjects included pediatric patients (aged < 16 years) who were treated by North Carolina EMS between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2016, for substance misuse or intoxication, according to EMS patient records. Substance misuse or intoxication refers to the consumption of any over-the-counter (OTC), prescription, or controlled substance outside of medical recommendation as suspected or confirmed by EMS. Patients whose records indicated that prescription medications were taken in an abusive manner not consistent with their indicated use were included in the study. Patients were excluded if duplicate records were created for the same patient case report or if the reason for transport was an interfacility transfer.

Study Protocol

Pediatric patients were included in the study if the free-text patient narrative field in Continuum included any of the following keyword search terms: “substance,” “alcohol/alcoholics/alcoholism,” “heroin,” “opioid,” “vodka,” “beer,” “gin,” “wine,” “etoh,” “codeine,” “fentanyl,” “hydrocodone,” “morphine,” “hydromorphone,” “oxycontin,” “Vicodin,” “methadone,” “oxycodone,” “naloxone,” “cocaine,” “overdose,” “weed,” “marijuana,” “acid,” “LSD,” “PCP,” “cough syrup,” “misuse,” “molly,” “MDMA,” “high,” “mushroom,” “prescription drug,” “abuse,” “mephedrone,” “bath salts,” “meth,” “cathinone,” “meth-amphetamine,” “moonshine,” “pot,” “edible,” “THC,” “MJ,” “cannab,” “cannabis,” “benzodiazepine,” “Xanax,” “valium,” “benzo,” “downers,” “alprazolam,” “diazepam,” “lorazepam,” “clonazepam,” “overdose,” “drug,” or “pill.”

All North Carolina EMS agencies, with the exception of one large urban agency, were included in data analysis; at the time of this study, the excluded agency used a self-standardized method of data entry that did not provide the details required to determine drug use within the free-text patient narrative field. After applying the keyword search to the data, two research members independently reviewed each patient care report to determine if cases indicated known or suspected drug misuse. In the event of reviewer disagreement, each case was discussed by the reviewers and a third member of the research team to achieve consensus.

Measures

Substance use was described for the entire sample. Subjects were stratified based on sex, age, race, region of encounter, location of encounter, urbanicity, polysubstance use, self-harm, and whether they were transported by EMS or not. Cases for which EMS transport was unknown were recorded as not transported, as no hospital destination was entered into Continuum.

Upon reading the patient narrative, the two independent reviewers manually classified the intent of drug misuse, category of drug misused, source of the misused drug, and intended use of the misused drug. The intent of drug misuse was classified as “accidental,” “recreational,” or “self-harm.” Intent for self-harm was determined if the patient narrative included explicit terms of suicidality from the patient, family members, or bystanders as noted by EMS. Applying similar close readings of cases, reviewers determined if cases included recreational and accidental drug use. The category of drug misuse was classified as: “marijuana,” “opioid,” “alcohol,” “stimulant,” “benzodiazepine,” “acetaminophen,” “antidepressants,” or “other” based on EMS documentation. “Stimulant” drugs primarily consisted of illicit sources of stimulants (e.g., methamphetamine and amphetamine derivatives) and stimulants used for attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). “Other” drugs consisted of otherwise unclassified or unknown drugs. After independent review and documentation, reviewers discussed discrepancies until a consensus was reached to determine case inclusion and categorize drugs used and intent of use. The sources of 3 drug classifications, including benzodiazepines, opioids, and stimulants, were further described. Sources included the patient’s own prescription, the prescription of another known individual, an unknown prescription source, an illicit source, and an unknown source.

Patient age was classified as infant/preschool (0–5 years), preadolescent (6–11 years), and adolescent (12–15 years). Region was defined as Coastal Plain (Eastern), Piedmont (Central), and Mountains (Western). Patient urbanicity was defined according to the North Carolina Rural Center, which defines a rural county as “a county with an average population density of 250 people per square mile or less” and an urban county as “a county with an average population density above 750 people per square mile.” Counties with a population density between 250 and 750 people per square mile were defined as regional city and suburban counties. Cases were grouped by the incident county and presented as a percentage of county population using pediatric population data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.9 Patients were assigned to the polysubstance misuse category if there was any evidence of more than one substance misused. These two or more substances did not have to be from different drug categories to be considered polysubstance misuse (e.g., use of fentanyl and oxycodone).

Analysis

All descriptive statistical analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, Washington).

Results

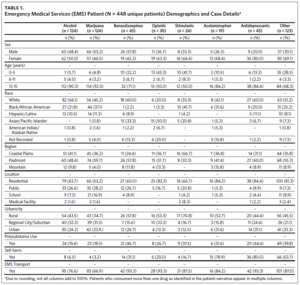

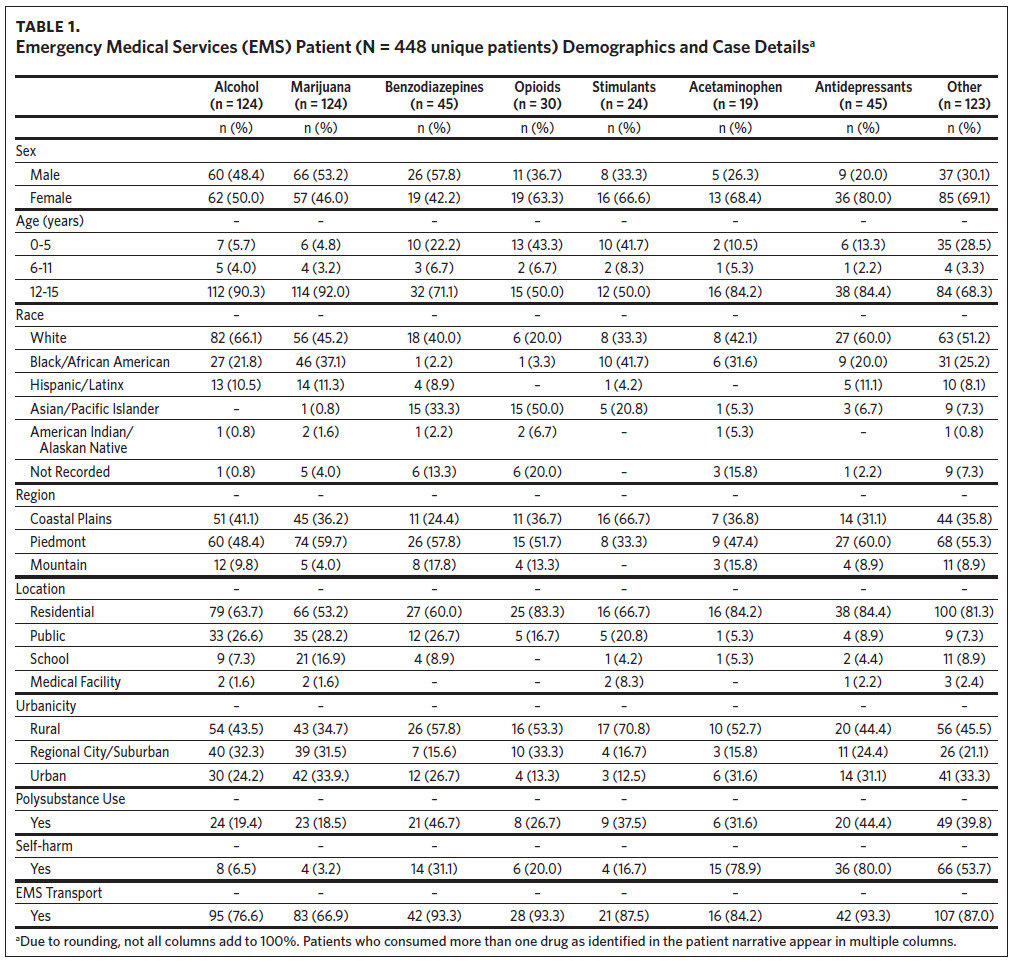

For the calendar year 2016, 45,855 total pediatric EMS encounters were documented in Continuum. Applying the free-text keyword search for initial identification of suspected substance misuse resulted in 800 cases. After independent review of each case, 448 unique encounters of pediatric substance misuse were isolated for the study population (Table 1). Among the study population, the majority were female (n = 254, 56.7%), White (n = 228, 50.9%), adolescent (n = 330, 73.7%), and resided in the Piedmont, or Central, region (n = 239, 53.3%) of North Carolina. A plurality of cases occurred in rural counties (n = 207, 46.2%), followed by urban (n = 125, 27.9%) and regional city/suburban counties (n = 115, 25.8%).

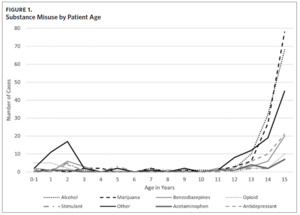

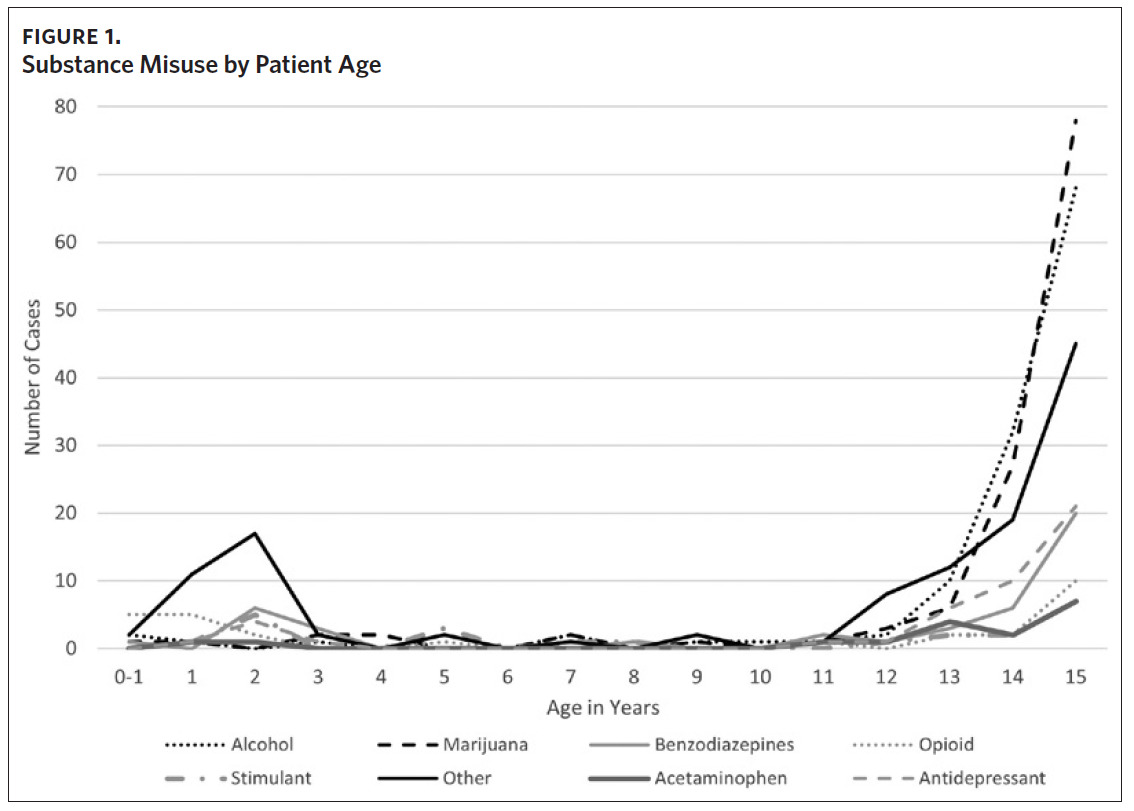

When accounting for counties’ pediatric populations to establish substance use rates per capita, urban counties had the highest rate (2.17 per 10,000), followed by regional city/suburban counties (1.96 per 10,000), and rural counties (1.81 per 10,000). Drug misuse was found to be highest among older pediatric patients (Figure 1). EMS was most often called to residential locations (n = 307, 68.5%), with a large proportion of calls also originating from public locations (n = 85, 19.0%) and schools (n = 47, 10.5%). Following evaluation, EMS transported patients in 80.6% (n = 361) of the encounters.

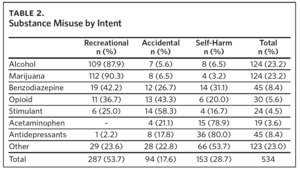

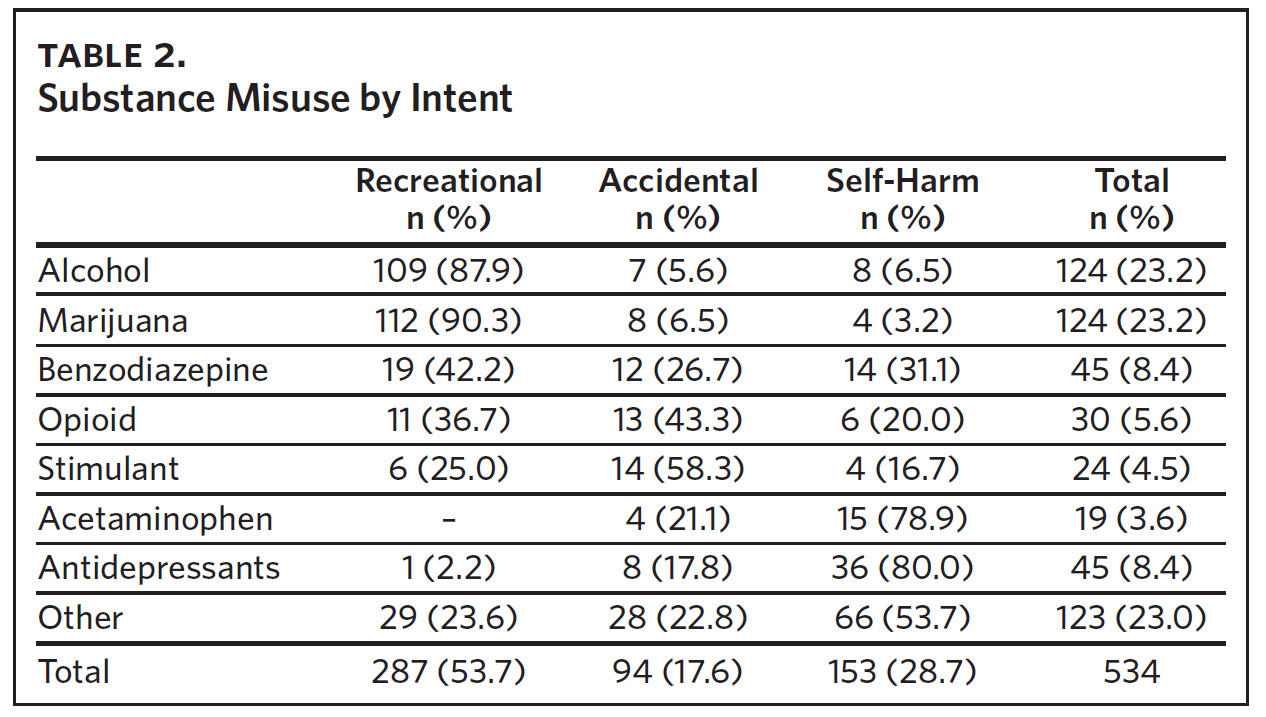

Among the 448 unique cases, there were 534 instances of drug misuse. The most common substances identified were alcohol and marijuana, each identified in 124 (27.7%) cases (Table 2). A large portion of pediatric substance use calls included benzodiazepines (n = 45, 10.0%) or antidepressant misuse (n = 45, 10.0%). A smaller subset of cases included opioid (n = 30, 6.7%), stimulant (n = 24, 5.4%), and acetaminophen (n = 19, 4.2%) misuse. There were 123 (27.4%) cases of substance misuse identified as “other.” These medications included antihistamines (n = 18), antipsychotics (n = 11), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (n = 10), antiepileptics (n = 10), cough suppressants (n = 6), and several other drugs with less than five cases per class. Of the 123 cases involving “other” drugs, 25 (20.3%) were not identifiable in patient records. There was evidence of polysubstance use in 84 (18.6%) encounters, of which 54 (64.3%) patients were female.

Three main groups of patients were identified among the encounters, including unintentional substance ingestion, recreational use, and intent for self-harm (Table 2). Of the 534 instances of drug misuse, the predominant intent was recreational (n = 287, 53.7%), followed by self-harm (n = 153, 28.7%) and accidental (n = 94, 17.6%). The most common substances used for recreational purposes were marijuana (n = 112, 39.0%) and alcohol (n = 109, 38.0%). The majority of recreational users were adolescents (93.0%) with a mean age of 14 years (data not shown). Accidental substance ingestion accounted for 92 EMS encounters (20.5%), the majority of which were in the infant/preschool age group (n = 77, 81.9%), with a mean age of 2.2 years (data not shown).

EMS clinicians found evidence of intent for self-harm in 113 unique encounters (25.2%) (data not shown). Of these cases, the majority of patients were female (n = 90, 79.6%) and White (n = 59, 52.2%). “Other” substances were most commonly misused for self-harm (n = 66, 58.4%). Many cases of self-harm (n = 45, 39.8%) involved polysubstance use. Regarding location, 89 of the 113 (78.8%) instances of self-harm occurred in residential locations, 7 (6.2%) were in public locations, 11 (9.7%) were in schools, and 3 (2.7%) were from a medical facility. Rural counties had 49 (43.4%) instances of self-harm, while regional city/suburban counties had 23 (20.4%) and urban counties accounted for 41 cases (36.3%).

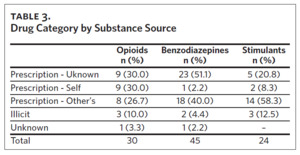

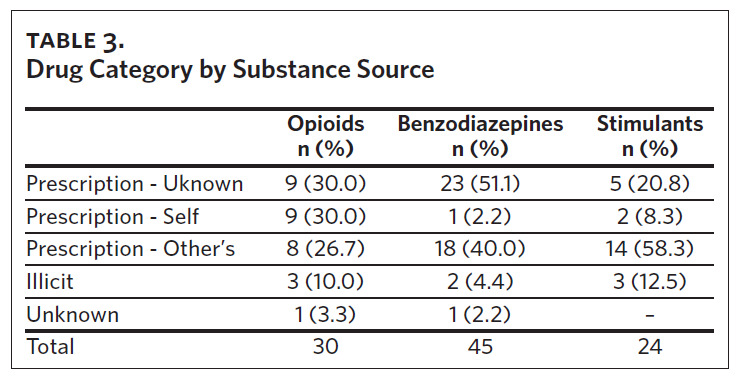

The source of drugs varied within the 3 major classifications of benzodiazepines, opioids, and stimulants (Table 3). Though the majority of these drugs were acquired through a prescription source (n = 89, 89.9%), the predominant source of benzodiazepines acquisition was through an unknown individual’s prescription (n = 23, 51.1%) while the primary sources for stimulants were prescriptions written for a known individual (n = 14, 58.3%). Although prescriptions were the most common route of opioid drug acquisition, prescription types were evenly divided among unknown (n = 9, 30.0%), self (n = 9, 30.0%), and other known (n = 8, 26.7%) sources.

Discussion

This study characterizes the landscape of pediatric substance misuse in North Carolina, identifying demographic, geographic, and substance use trends. With implications for public health and EMS resource utilization and education, it is important to recognize that EMS plays a vital role in the frontline care of substance misuse patients. Counties and EMS systems have unique challenges based on a variety of factors, including patient demographics, comorbidities, and ease of access to tertiary care centers. Geographically, cases tended to cluster around urban and suburban areas, but numerous cases were identified throughout rural areas. When considering the counties’ pediatric populations to establish substance misuse rates per capita, there was a more equal distribution of cases across geographic regions, as urban counties had higher per capita rates given the population density of these counties. Tertiary care destinations, with preference to those with pediatric capabilities, should follow pediatric population health needs.

Among all cases, there was a bimodal age distribution with a predominance of infants/preschoolers and adolescents, accounting for more than 95% of all cases. The main distinctions between these two groups were intent and substances used. In the youngest age group, all cases were accidental, and most drugs used fell into the “other” category. These EMS encounters were largely characterized by unintentional ingestion among young children with access to medications in the home. Accidental substance use in young children carries a high risk of significant morbidity and mortality, as even small doses of medications in this age group can have drastic physiologic effects. EMS and tertiary care destinations should be prepared to identify likely sources of drug overdose and misuse and treat accordingly, using observational data on scene and public health data from this and other studies.

Recreational substance use was seen mostly in the adolescent age group, most commonly with marijuana and alcohol. Alcohol and marijuana are among the most widely used drugs as reported by adolescents,10 which is likely the result of not only individual risk factors but sociopolitical, cultural, family, and peer influence as well.11 Of note, at the time of this study, marijuana use was neither legalized for medical nor recreational use in North Carolina.12 With continued use and limited capacity to fully realize the long-term consequences of drug use, several studies have documented that alcohol and marijuana use in adolescents can lead to abnormalities in brain function, specifically neurocognition, brain volume, and white matter quality.13 Children do not fully perceive long-term consequences, and therefore, they may not understand the potential risks and medical interactions of drugs they consume; this can result in unintended and undesired outcomes in children who consume drugs. Perhaps the easiest substances to access are prescription and OTC medications already in the home.14 Even though some prescription and OTC medications are not often thought of in the same way as more typical drugs of misuse, we must recognize their potential for misuse and develop harm-reduction strategies and policies.

In this study, there was a pervasive presence of substance misuse with the intent for self-harm, representing almost a quarter of all encounters. There were twice as many attempts at self-harm using prescription medications than OTC medications, even though OTC medications are more widely and easily available. Perhaps the most alarming detail regarding those who were intending to harm themselves was that over 80% were female, and all were adolescents. Other studies have affirmed this trend, especially as it relates to adolescent females.15,16 This trend may be partly due to differences by gender in methods of suicide and self-harm, including firearms, pesticide poisoning, or hanging.16 There is clearly a gender and age divide in attempts to self-harm, and more resources and education should be devoted to suicide prevention.

In the time since data analysis was completed for this study, a global pandemic ensued in March 2020. During this time, there was an exponential increase in EMS calls, causing increased pressure on EMS dispatch centers and EMS workload.17 Additionally, risk factors for adolescent substance misuse—such as early life stress, social isolation, and increased monotony—have increased over the duration of the pandemic, placing a greater number of youths at risk for overdose.18 Further study is needed to quantify and characterize the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on overdose and substance misuse in the North Carolina pediatric population receiving prehospital care.

Various substance misuse prevention strategies have been implemented over decades, targeting different stakeholders. Project Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E) targeted school-age youth in the 1990s and 2000s. Despite the program’s widespread use and expansive budget, it has been found to be largely ineffective.16 In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention formed the Preventing Overdoses and Treatment Exposures Task Force (PROTECT), aimed at safe medication storage and improvements in child safety features in medication packaging. This task force has made great strides in standardizing safety measures, specifically in OTC medication preparations.19 Few programs targeting adolescent education have shown long-term effectiveness in reducing risk of drug use, with some newer programs showing promising results for reducing overdose mortality.20

Furthermore, the United States has experienced an extensive gutting of in-patient and out-patient mental health services, including drug treatment centers.21 While cuts to mental health services have been increasing, fentanyl—an extremely potent synthetic opioid—has emerged as a prominent contributor to opioid-related fatalities. A significant factor behind fentanyl’s impact is the production of counterfeit tablets that mimic commonly abused prescription drugs.20 Even when locally available, accessing mental health resources can be a costly burden for patients, and prehospital transport to such facilities may not be covered by insurance.22,23 Recognition and treatment of pediatric substance misuse requires a multilevel approach to affecting change. EMS clinicians can and should be an essential arm of a comprehensive approach to addressing pediatric substance misuse identification and treatment.

EMS clinicians are at the forefront of patient care response, responding to time-sensitive health conditions and caring for vulnerable populations. As such, EMS clinicians should first and foremost be aware of the physiologic effects of misused drugs on pediatric patients. Second, EMS should be cognizant of substance use harm reduction programs in their communities, as referrals to these resources can assist patients and families. For example, a common outcome for prehospital opioid overdose patients is naloxone administration. However, as opioids were not among the most common drug exposures to pediatrics, EMS must be prepared to identify and treat pediatric patients exposed to a wider variety of drugs beyond opioids. In order to halt the ongoing and pervasive public health crisis of pediatric substance misuse, EMS must become a core component of further education and intervention, as they are at the forefront of drug overdose and exposure response.

Limitations

This study is not without limitation. Prehospital data only provide a snapshot of the patient encounter and do not necessarily relay a patient’s confirmed diagnosis. Without hospital data, it is difficult to accurately assess which substances a patient may have misused.

Some misclassification of patients’ drug use and intent is expected. Not only is it impossible to account for all spelling variations in drug names, but cultural variations in slang may have resulted in missed cases or lack of clinician documentation. Furthermore, unconscious or noncommunicative patients are unable to describe their symptoms and histories, which may have resulted in missed cases. Though EMS can identify substance use as the likely cause of a patient’s condition, they are not able to identify drugs used in all cases, resulting in some cases of drug use being labelled as “other” if they were unknown. Though the authors identified main drug categories of concern based on legality of drugs, prevalence of use (e.g., benzodiazepines can be used for several common mental health conditions), and ease of accessibility, some loss of clarity in data interpretation due to grouping is expected. Additionally, since this study focused on substance misuse, underreported cases are possible due to topic sensitivity and fear of legal ramifications.

In addition, one large urban North Carolina county was removed from analysis due to issues with data transfer to Continuum. EMS systems may develop their own methods to link their data system to Continuum or may use a third party. As such, without a uniform method of data delivery into Continuum, data transfer issues arise.

Future studies should focus on linking EMS data to hospital data to corroborate prehospital clinician assessments of substance misuse in pediatric patients with confirmatory testing and evaluations in the emergency department. This endeavor was outside the scope of our work. The completion of a link would allow for access to outcomes-driven evaluations and comparisons of the accuracy of prehospital assessments with those in the emergency department.

Conclusions

Pediatric substance misuse is a significant phenomenon in the prehospital environment. Marijuana and alcohol were the most commonly misused substances, followed by benzodiazepines and antidepressants. Most unintentional encounters were in young children, and the majority of all other cases were in the adolescent age group. A quarter of substance misuse encounters involved the intent for self-harm, over 80% of which were female. Instances of pediatric drug consumption can be accidental, recreational, or intended for self-harm; as such, EMS clinicians must be aware of the signs and symptoms, medical treatments and facilities, and policies pertaining to substance use. EMS clinicians hold a unique role in the community and should be an essential component of targeted approaches to combat pediatric substance misuse.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to acknowledge the contributions of Rawaa Al-Rifaie to the data acquisition process.

Declaration of interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.