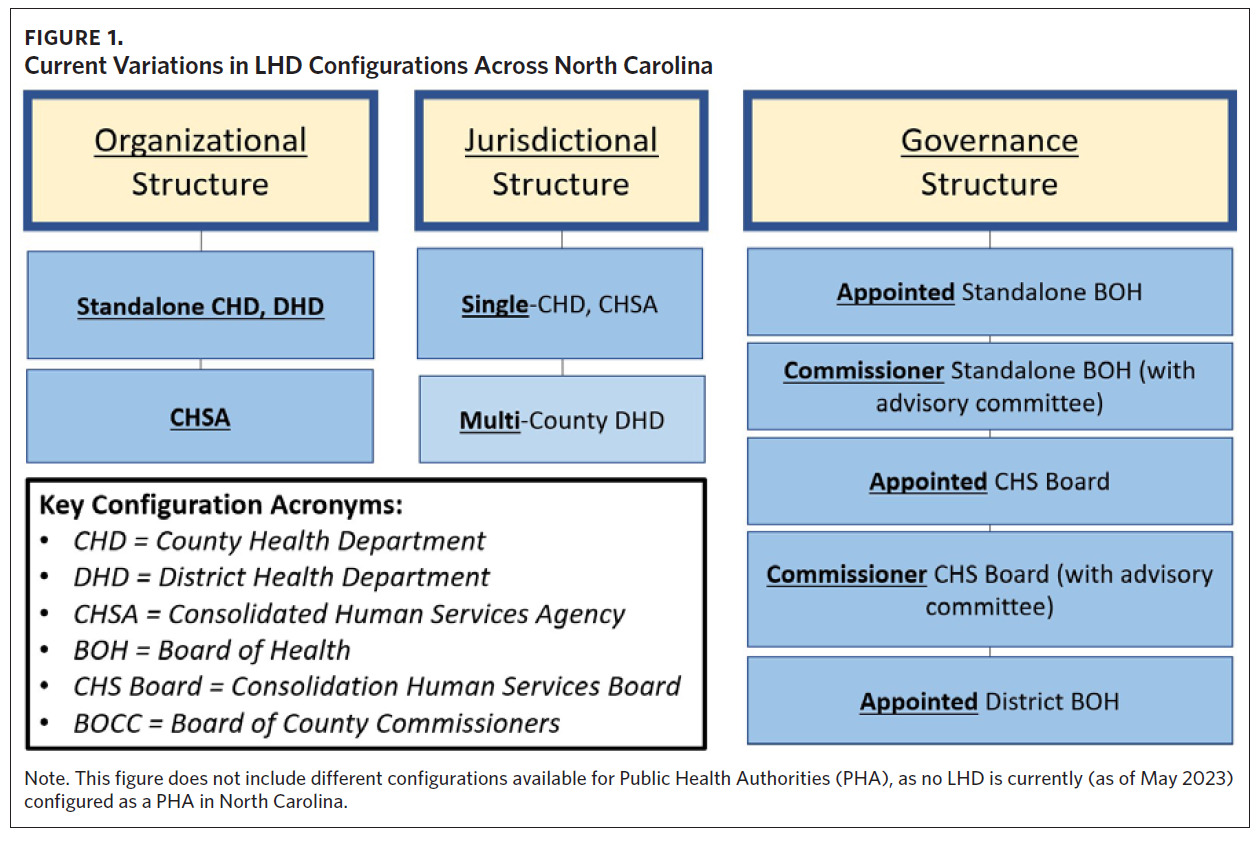

Under the North Carolina General Statutes, every county must have a local health department (LHD), a local health director (Director), and a governing board of health (BOH). The exact organizational and governance structure of these components can vary.1 Traditionally, LHDs are single county health departments (CHDs), in which services are delivered to a single county, with governance provided by an appointed, county-specific BOH (Standalone BOH). Individual counties may also form consolidated human services agencies (CHSAs), in which multiple county human services functions or departments are consolidated into a single agency. CHSAs may be governed directly by a Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) or by an appointed consolidated human services (CHS) board, which must include members from a wide range of human services backgrounds. Counties may opt to form a multi-county district health department (DHD) that provides services for the residents of all counties in the district. DHDs are governed by a District BOH and are composed of members from each of the constitutive counties. Lastly, counties may opt to form a public health authority (PHA) that is entirely removed from county management (an additional configuration—a public hospital authority—is allowable by a 1997 law that only applies to Cabarrus County).2 Collectively, the organizational structure (CHD, CHSA, DHD, or PHA) and governance structure (Appointed Standalone BOH, BOCC as Standalone BOH, Appointed CHS Board, BOCC as CHS Board, or District BOH) constitute the LHD’s configuration (Figure 1).

In 2012, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a law (Session Law 2012-126) that substantially modified the availability and structure of LHD configurations across the state.3 Among other changes, it allowed BOCCs from any county to form CHSAs and/or to assume the legal powers and duties of a Standalone BOH or CHS board (thus forming a Commissioner BOH). Forming a Commissioner BOH must include the formation of an advisory committee reflecting the membership composition of a Standalone BOH, though the committee has no legal authority. Session Law 2012-126 also allowed CHSAs to remove LHD employees from what is now the State Human Resources Act (SHRA) and place them solely under county personnel policies.4

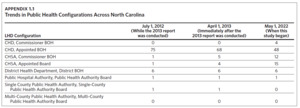

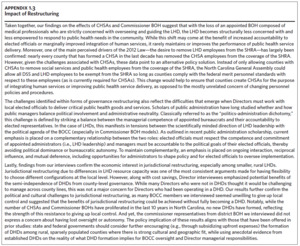

The configurations now widely available in North Carolina represent three distinct forms of restructuring when compared to a CHD with an appointed Standalone BOH: organizational restructuring (CHSAs), jurisdictional restructuring (DHDs), and governance restructuring (Commissioner BOH). In one way or another, each restructuring integrates decision-making processes for the LHD, ultimately shifting the power dynamics for the LHD-BOH relationship and, therefore, the prioritization of public health in the community. In the last 10 years, there has been a substantial proliferation in the different configurations for local governmental public health in North Carolina (Appendix 1.1), providing a natural opportunity to study how such variations impact LHD activity, including the LHD-BOH relationship (for an updated list of configurations, see the interactive maps from the Organization and Governance of NC Human Services Agencies at https://humanservices.sog.unc.edu/ visualization-all/).

Methods

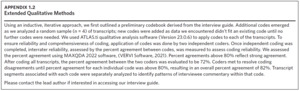

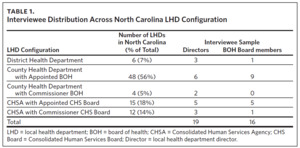

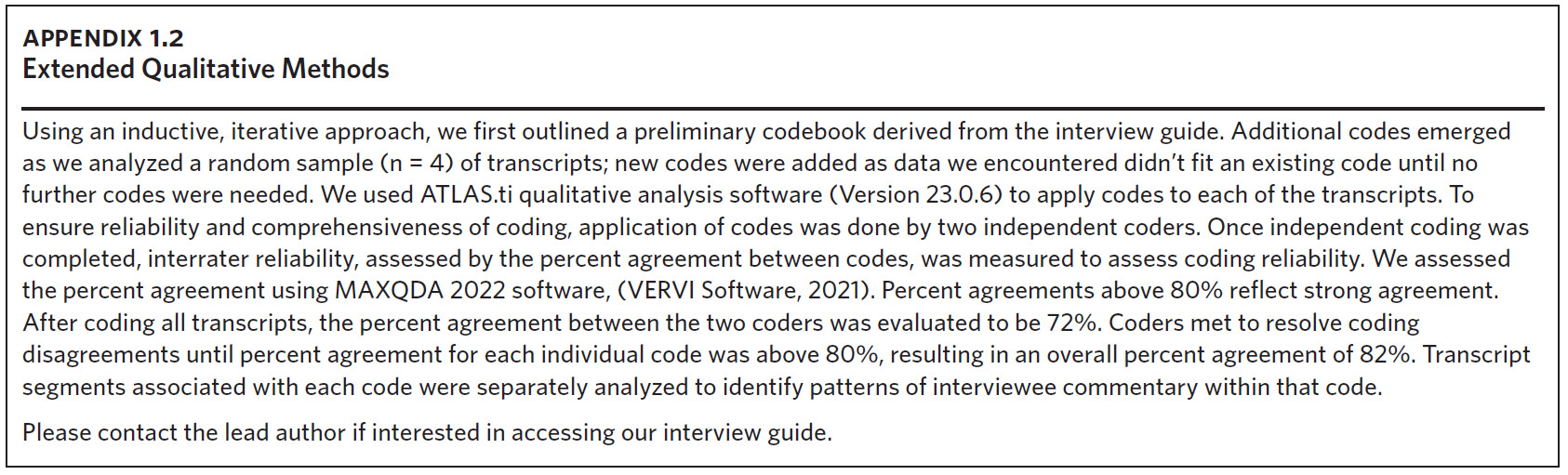

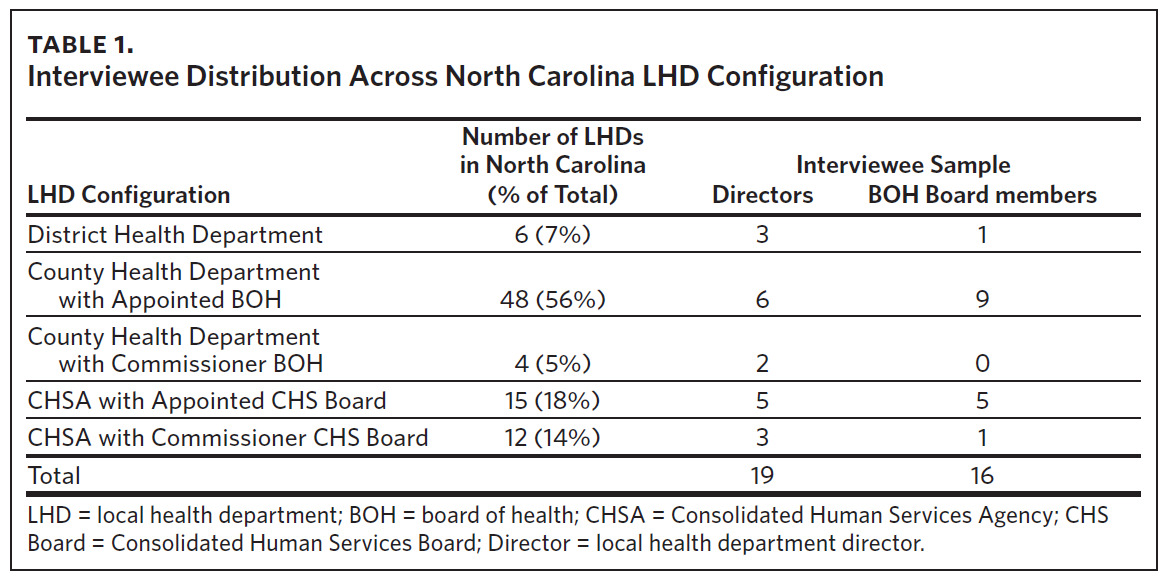

To collect data for this analysis, we conducted a set of semi-structured interviews with Directors and their BOH members across the state of North Carolina. Our sample of interviewees consisted of 19 Directors and 16 BOH members (Table 1). We developed an interview guide for all semi-structured interviews that included questions about the overall relationship between the LHD and the BOH, the impact of each of the three forms of restructuring on the work of the LHD, and the variation in local public health configurations across the state. We employed conventional content analysis to derive themes from interview transcripts (Appendix 1.2).5

Results

BOH Engagement and Opportunities for Improvement

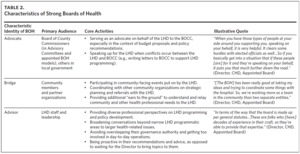

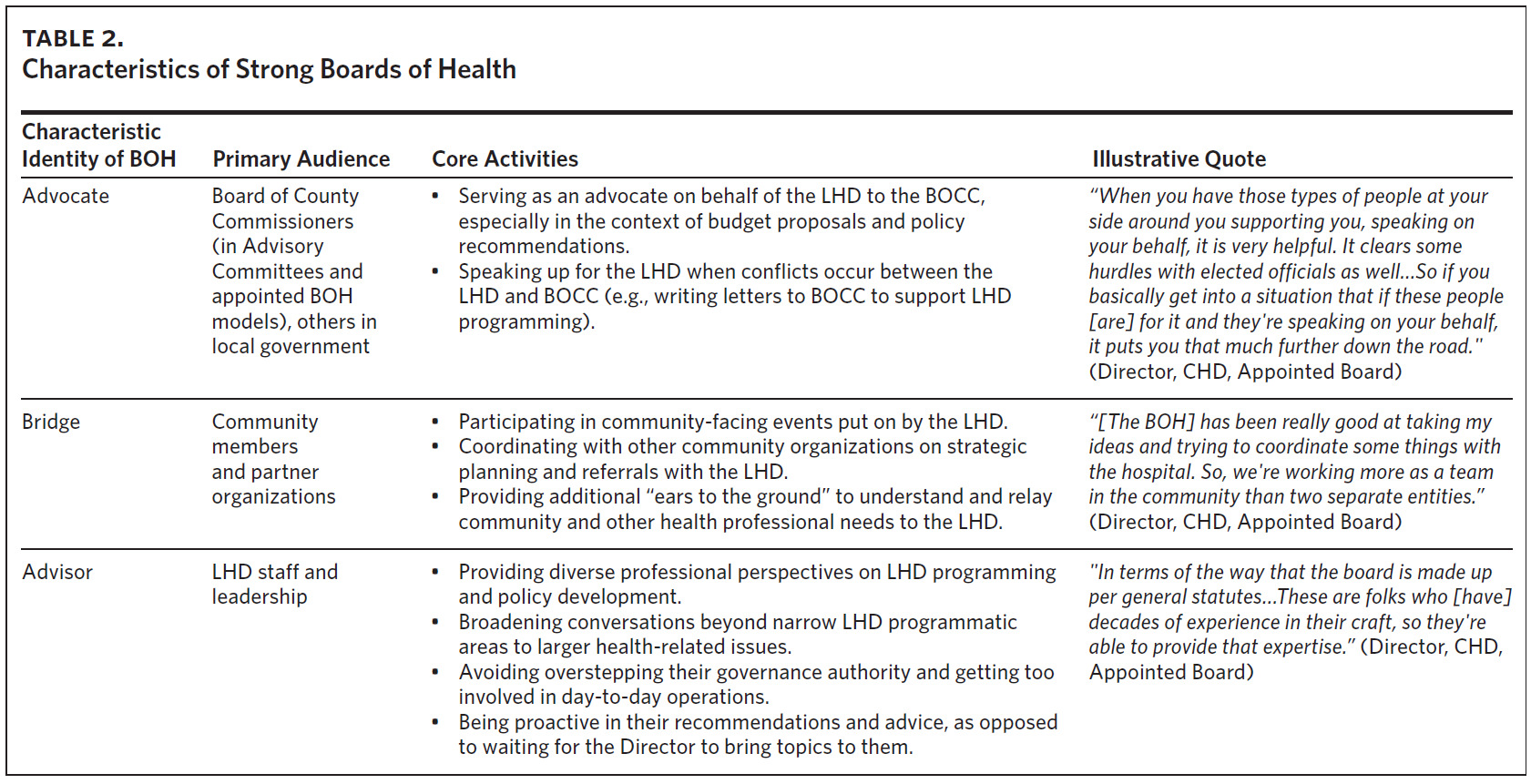

The influence of BOHs varied considerably across different configurations, though examples of weak and strong BOHs were present in every model. Weak BOHs were marked by poor attendance at meetings, passive reception of LHD programming reports, and a conceptualization of the BOH’s role as limited to voting on items identified by state statutes and reviewing the LHD’s policies and budgets, as minimally required for accreditation. Alternatively, strong BOHs were often defined by their capacity to fulfill three core identities on behalf of the LHD: advisor, bridge, and advocate (Table 2). Most BOHs were much more likely to demonstrate advisor characteristics than those of an advocate or a bridge.

The bare minimum of their requirements, they are doing that… I guess if you look at Board of Health responsibilities, their administrative stuff, they do that hands-down no problem. The advocacy piece…I think there is interest and a lack of understanding about how much and what they can do (Director, CHD, Appointed Board).

Interviewees identified opportunities for BOH improvement. Directors emphasized the need to better educate their BOH on LHD programs and the scope of their legal mandates. Likewise, Directors and BOH members desired additional direction on the responsibilities of BOH (e.g., how to best evaluate the LHD director). Many Directors also desired several changes to BOH composition, including the addition of categories of membership that are not currently mandated by law: non-voting young people, mental health professionals, emergency management leaders, nutritionists, non-allopathic health professionals, and more community participants. Likewise, Directors expressed a desire for training on how to identify potential BOH members with a genuine interest in public health and ensure authentic representation across all positions.

That’s the health director’s responsibility to make sure that they build a team that functions as more than just a sounding board, to build a team that has an interest in public health and wants to help you with your health department. It also depends on how much control that health director wants to have and how much they want to share (Director, CHD, Commissioner BOH).

My understanding of what the board’s empowered to do, it’s not clear. There’s certain things we have to vote on, like the budget. Or we have to evaluate the health director…But if there’s policies that we’re supposed to help develop, I don’t know what those are (BOH Member (Commissioner), CHD Appointed Board).

Trade-offs and Decision-making Between LHD Configurations

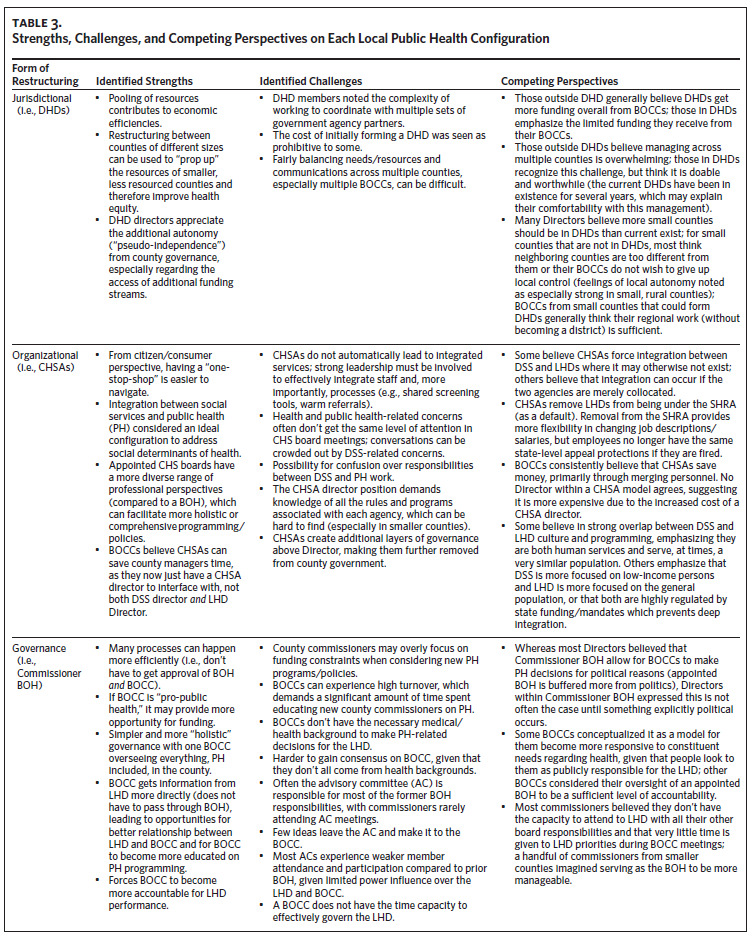

We asked interviewees about what they perceived as the strengths and weaknesses of each configuration, regardless of their current model. Table 3 outlines common interviewee responses to this question, along with examples of competing perspectives.

Several tradeoffs centered on how each model prioritized county resources and the attention given to public health. Commissioner BOHs enabled more efficient access to the funding and policymaking authority of the BOCC when the goals of the LHD and BOCC aligned but created a risk of LHD decision-making becoming influenced by local politics. DHD directors enjoyed how their model allowed for some independence from county management, though they noted the limited levels of county funding allocated for their work. Directors within CHSAs appreciated how at times their structure enabled better integration of resources between social services and public health, but many expressed frustrations over how CHS board meetings became dominated by the concerns of other human services (often social services). They also expressed concerns about how being overseen by a CHSA director or county manager (as opposed to the BOH) further removed them from a more direct relationship with the BOCC and the opportunities that such a direct relationship presents to voice their perspective to BOCC members.

I think that sometimes public health can get buried under the social services piece, right? You think about social services at the end of the day, that they’re protecting vulnerable people, and they’re having to do some really difficult things. And that can overshadow some of the preventative work and programming that public health needs to do and should do in the community (Director, CHD, Appointed Board).

Population size was also consistently discussed when considering alternative models, especially among county commissioners. For example, BOCCs from smaller counties found it more feasible for them to govern the LHD (2 of the 4 CHDs with a Commissioner BOH in North Carolina have fewer than 20,000 citizens). Alternatively, BOCCs from larger counties found it more important to have closer oversight of the LHD and DSS through forming a CHSA (8 of the 10 largest counties by population size in the state are CHSAs). Many interviewees recommended that smaller counties form DHDs.

Several strengths and weaknesses of each configuration were interrelated. Often, the identified strength or weakness reflected a different management preference among Directors and BOH members, marked by the degree of interaction between one or more governing entities. Whereas some Directors appreciated more direct access to the BOCC in a Commissioner BOH, others preferred how an appointed BOH protected them from local politics. Whereas some Directors appreciated having a multidisciplinary appointed BOH to report to and utilize as a sounding board and advocate, others were content or even appreciated the institution’s absence, given what they perceived as the appointed BOH’s limited utility and the time it took to manage BOH relationships. Likewise, whereas some county commissioners thought that appointed BOH oversight of the LHD provided a sufficient level of public accountability, others speculated that having more direct county control—whether through a CHSA and/or a Commissioner BOH—was necessary.

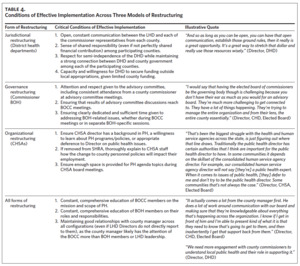

Conditions of Effective Implementation

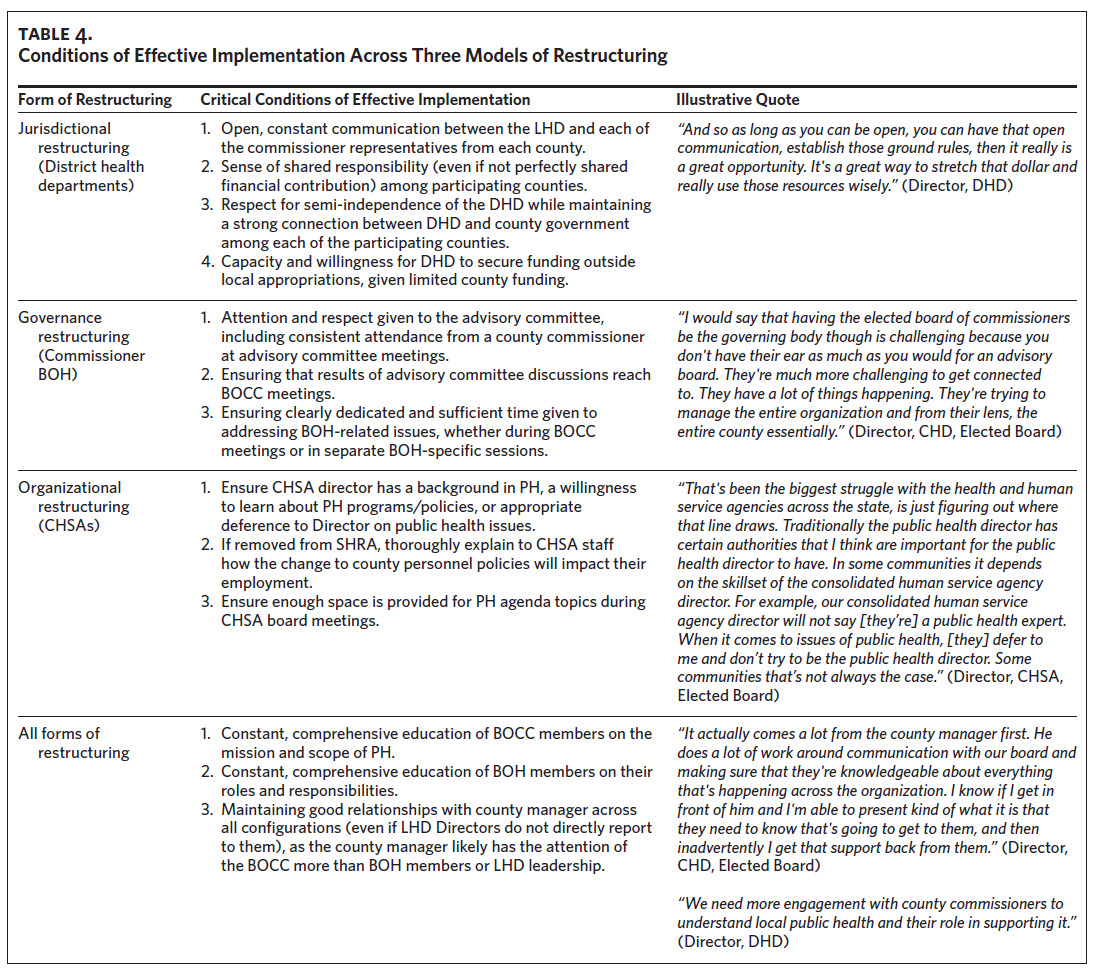

Interviewees identified several conditions in which the implementation of each model would more likely be successful for advancing the mission of public health (Table 4). Most of these conditions emphasized improvements to one or more relationships between the various entities involved in governance, with a consistent emphasis on constant, transparent communication. Interviewees also emphasized training to learn about the constraints and resources available for each entity.

While examples of successful implementation were identified across each model, organizational and governance restructuring were consistently noted as challenging to implement. Directors indicated that managing LHD operations within CHSAs was unwieldy, that the additional human service divisions (especially social services) often made it challenging to sufficiently focus on public health concerns, and that meaningful integration of human services was challenging. Likewise, most interviewees perceived BOCC models to be too sensitive to political demands and BOCC members to be incapable, due to lack of time or expertise, of effectively governing the LHD. In general, both Commissioner BOH and CHSA models were characterized as structurally distracting from the singular focus on public health that CHDs and DHDs are more likely to provide, despite the benefits CHSAs and Commissioner BOH models may also provide. Several Directors went so far as to propose the elimination of CHSAs and Commissioner BOHs in North Carolina. Notably, no member of a CHD with an Appointed BOH or DHD expressed major complaints about working within their model.

When we had a Board of Health, we met with them monthly, and it was an hour to an hour and a half meeting…We got to sit and discuss lots of issues, and everybody got to verbalize what they wanted to verbalize. Now we go to the county commissioners’ meetings quarterly and they do the county meeting and then they do the consolidated meeting. I feel like we’re at the end, and whether it’s been a good meeting or a bad meeting, we’re at the end and it’s just, we do our spiel (Director, CHSA, Elected Board).

Perceived Origins of Session Law 2012-126

These critiques align with commentary on what interviewees generally perceived as the 2012 law’s origin. Interviewees suggested that SL-2012-126 was adopted due to instances in which county management wished to terminate the LHD or DSS director but could not do so under the traditional CHD model (notably, hiring/terminating the Director was considered by BOH members to be one of their most important authorities). Likewise, interviewees suggested that many BOCCs formed CHSAs because it allowed them to alter personnel policies for the LHD and DSS, given that CHSA formation allowed LHD and DSS staff to be placed under county personnel policies. In either case, the perceived intent of the BOCCs was not to improve service delivery through the meaningful integration of human services (via CHSAs) or to exercise improved governance over LHD programming (in Commissioner BOH models). To this end, some Directors remarked that if there were other mechanisms for BOCCs to address personnel issues or if these issues never existed, configuration restructuring would not have occurred. Less frequently, interviewees perceived that BOCCs pursued organizational restructuring to decrease the size of government or to save the county money, although no Director confirmed that CHSAs have in fact saved money. One interviewee noted that the LHD is one of the highest-revenue-generating departments of local government, which may have prompted interest among the BOCC for closer management of its operations.

In a lot of ways [this] is why some counties have elected to shift the Board of Health to the Board of Commissioners because they wanted to retain that ability to make the budgetary decisions as well as make the personnel related to decisions. Our board of commissioners oftentimes is not interested in making any of the other…They really just don’t want to be bothered with it unless it has to be a rule making policy decision…They’d rather the advisory board had the authority…to do all the obligations related to accreditation. However, the way it’s outlined currently, that’s not a possibility. It’s either all or nothing (Director, CHD, Elected Board).

Discussion

The BOH-LHD relationship can be a strong institution for advancing local public health, but it demands structural conditions as well as personal buy-in from both BOH members and LHD leadership. These conditions were not often present within our sample. While a handful of Directors considered BOHs invaluable to the work of the LHD, most argued that their BOH served, at best, as a passive sounding board. Given the instrumental role BOHs may have in local public health and their duty to uphold various statutory responsibilities, it is essential to educate and empower all those involved in local public health governance on how to better their ability to uphold those responsibilities.

Within North Carolina, training for new BOH members as well as ongoing training (provided at least once during an accreditation cycle) is required to satisfy state LHD accreditation requirements.6 However, the majority of this training focuses on educating new or current BOH members on the legal powers and responsibilities of BOH (e.g., how to adopt local public health rules). Based on the results of this study, additional training should be provided (to both BOH members and LHD leaders) on the skills and best practices associated with BOHs going beyond the “bare minimum” that is formally required by law or for accreditation so that they can become a stronger advocate, advisor, and bridge for the LHD. Given the dynamic pace at which public health challenges evolve, training should be given more frequently than accreditation cycles.

In advance of the changing legislation in 2012, scholars at the University of North Carolina School of Government interviewed local and state public health leaders on the perceived strengths and challenges of each configuration.7 However, since the study’s publication in 2013 (the “2013 Report”) there has been a substantial proliferation in the number of CHSAs and Commissioner BOHs.8 Given the overlapping research questions, we encourage our results to be reviewed in concert with and as a continuation of results from the 2013 Report.

The authors of the 2013 Report noted a fear among their interviewees that politics would control the LHD agenda within Commissioner BOH models and that the BOCC would not be capable of fulfilling the BOH’s responsibilities. The results of our study largely confirm both fears. Commissioner BOH models were described as overly focused on financial stewardship, liable to make decisions based on political pressures, and likely to largely relegate the majority of their BOH responsibilities to their advisory committee (a weakened institution compared to the BOH). Many directors noted that the influence of political pressures on public health decisions was especially challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic, a moment of crisis between public health and politics that could not have fully been anticipated when the 2013 report was conducted. However, a small handful of Directors noted that Commissioner BOH models are not entirely negative for the LHD, especially during seasons in which the LHD’s programming does not seriously conflict with the political interests of the BOCC. During such seasons of “peacetime” (Director, CHSA, Appointed Board), a Commissioner BOH can enable more efficient decisions and greater access to resources, with its advisory committee exercising the best advisor qualities of an appointed BOH (for an extended discussion on each form of restructuring, see Appendix 1.3).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis, most of which concern our sampling frame. We did not interview county managers, who play a critical role in local public health governance, though the role of county managers was often discussed among interviewees. County managers are especially influential within CHSAs, given their role in hiring and terminating the CHSA Director, and within LHDs with a Commissioner BOH, given the close relationship between county managers and BOCCs. Likewise, while we sought representation across each configuration, we were not able to contact and interview county commissioners from CHDs with a Commissioner BOH (in one instance the LHD director was not comfortable with them being interviewed, and in all other instances they were not reachable after several contact attempts). However, we were able to interview county commissioners from CHSAs governed by a Commissioner BOH, as well as county commissioners from other models. We also asked each county commissioner we interviewed about their thoughts on forming a Commissioner BOH.

Conclusions

We found that within North Carolina, a BOH is largely an underappreciated and underutilized institution across the state, even though it has the capacity to provide “invaluable support” (Director, DHD, Appointed Board) to the LHD when it fulfills core identities that go beyond what is minimally required by law. We also found that variations in local restructuring—organizational, jurisdictional, governance— strongly shape the LHD-BOH relationship, either by further empowering their activity or distracting them with concerns of other agencies or local political dynamics. When considering changes to local public health organization and governance, local practitioners and policymakers should consider how such changes will shift this relationship before making what is often a long-term solution for public health service delivery in the community. Given the most updated results from the recent proliferation of various organization and governance models across North Carolina, current BOCCs, BOHs, and Directors should reconsider whether governance shifts that may have happened several years ago reflect what is best for community health in their locality at the present time.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Kristi Nickodem (Assistant Professor of Public Law and Government, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for her assistance in helping us understand the options and requirements for public health organization and governance models under North Carolina law, as well as her assistance in helping us contextualize interviewee commentary.

Declaration of interests

All authors report no conflict of interest.