Social determinants of health (SDoH), the conditions in which people are born, work, live, and age, have a profound impact on morbidity and mortality.1 SDoH can affect the health of an individual by leading to unmet health-related social needs (e.g., food insecurity) that are associated with worse health and impaired chronic disease management.2 Older adults are particularly at risk of having unmet social needs because of limited finances (e.g., receiving a fixed income) and/or limited functional mobility (e.g., ability to complete daily activities).3,4 Frailty, a syndrome of decreased physiological and day-to-day functional reserve that renders older adults vulnerable to stressors, can lead to unmet social needs.5,6

A growing number of national and state health care organizations have recommended that health systems address patients’ unmet health-related social needs as a routine part of clinical care.7–13 Also, initiatives such as the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit recommend an assessment of older adults’ day-to-day function.14 With these recommendations, there has been increasing investment in integrating social and function-focused care into health care settings.10,15,16 However, the resources to address patients’ social and functional needs (e.g., food, home health) often exist outside of traditional health care settings and require partnerships with community-based organizations.7,9,15,17 Further, we know little about what older adults perceive as the social and functional needs that most impact their lives.

To fill this gap, we conducted this study to characterize the perspectives of older adults with frailty and community-based organizations in regard to which social and functional needs impact older adults’ health and how to support them in addressing those needs. Additionally, our objective was to assess patients’ experiences with health care providers assessing their social and functional needs and to understand community organizations’ perceptions of partnering with health systems to assist older adults.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

We conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults with frailty and leaders/staff from community-based organizations. The Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Patients

We conducted interviews with adults who receive primary care through the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (AHWFB) health system, an integrated academic health system serving Central and Western North Carolina. The system comprises a tertiary care hospital, four community hospitals, and more than 300 ambulatory practices that all use a single electronic health record (EHR; EpicCare, Verona, WI). Patients were eligible if they: 1) were aged 65 years or older, 2) had a primary care provider (PCP) in the AHWFB system and were seen in their PCP’s clinic between May 2020 and May 2021, 3) lived in Forsyth County, 4) were frail, and 5) were at risk of having unmet social needs. Frailty was defined as having an electronic frailty index (eFI) greater than 0.21. The eFI is an automated digital marker based on the accumulated deficit model and utilizes data from the EHR to identify patients at risk of being frail.18 The eFI independently predicts mortality, hospitalizations, and injurious falls.18–20 The eFI is automatically calculated based on the data within the EHR, and it is stored in the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Translational Data Warehouse. To determine if patients could be at risk of unmet social needs, we used the 2019 Area Deprivation Index (ADI).21 The ADI is an established indicator of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage that aggregates estimates from the American Community Survey across domains of income, education, and health care access.22 Individual patients’ addresses that were listed in the EHR were geocoded at the census block group level and linked to their respective ADI by their census block group geoid. We defined patients as being at risk of having unmet social needs if they lived in a census block with an ADI greater than or equal to the 75th percentile. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English or if they had an ICD-10 diagnosis code related to dementia in the past two years.23

A study team member contacted a convenience sample of eligible patients by phone to explain the study purpose and procedures, review eligibility criteria, and determine patients’ interest in participating. Patients who agreed were scheduled for an interview by phone or video teleconference. All patients who completed an interview received a $20 gift card.

Community-based Organizations

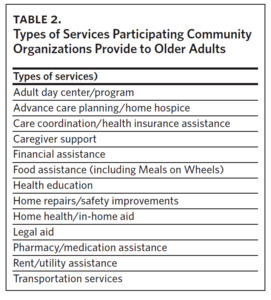

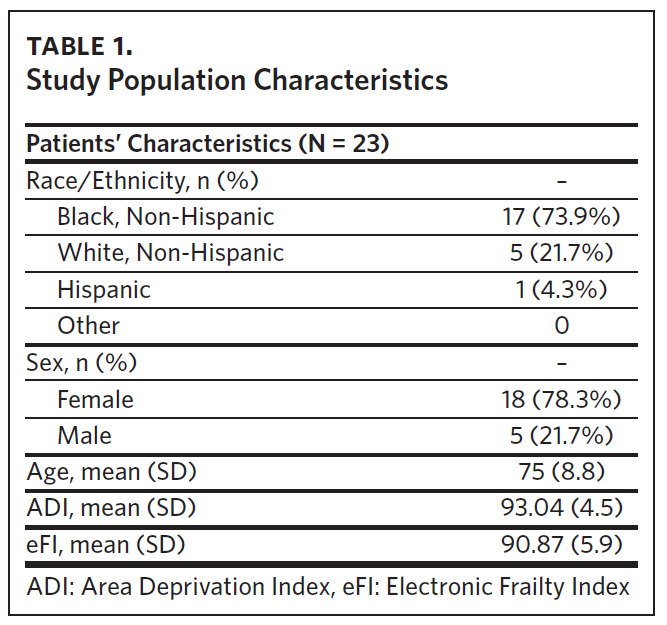

We conducted interviews with leaders and staff from community-based organizations in Forsyth County, North Carolina. Staff members who were involved in leadership and/ or programming at organizations that provided social and/or functional services for older adults were eligible. Social services included organizations that provided financial assistance and Meals on Wheels. Functional services included organizations that provide home health, home repairs for older adults, and Medicaid transportation services. All participants were aged 18 years or older and spoke English.

A study team member contacted staff members at eligible organizations by email or phone. If eligible participants did not respond, the team member attempted two additional contacts over a two-week interval. Participants who agreed were scheduled for an interview in person, by phone, or by video teleconference. After we reached out to known organizations, additional participants from other organizations were identified through snowball sampling. We used purposive sampling with the goal of having a heterogeneous sample of participants based on the services the organizations provide (e.g., home health, transportation services). All staff who completed an interview were entered into a raffle for a $100 gift card.

Data Collection

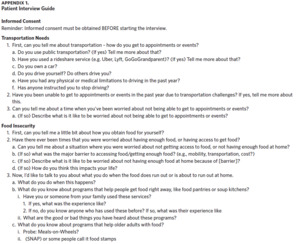

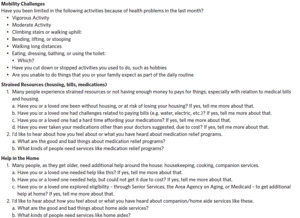

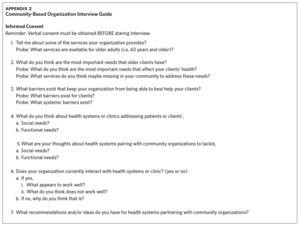

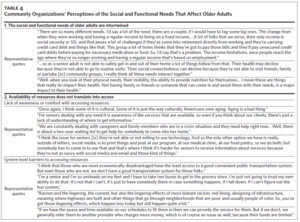

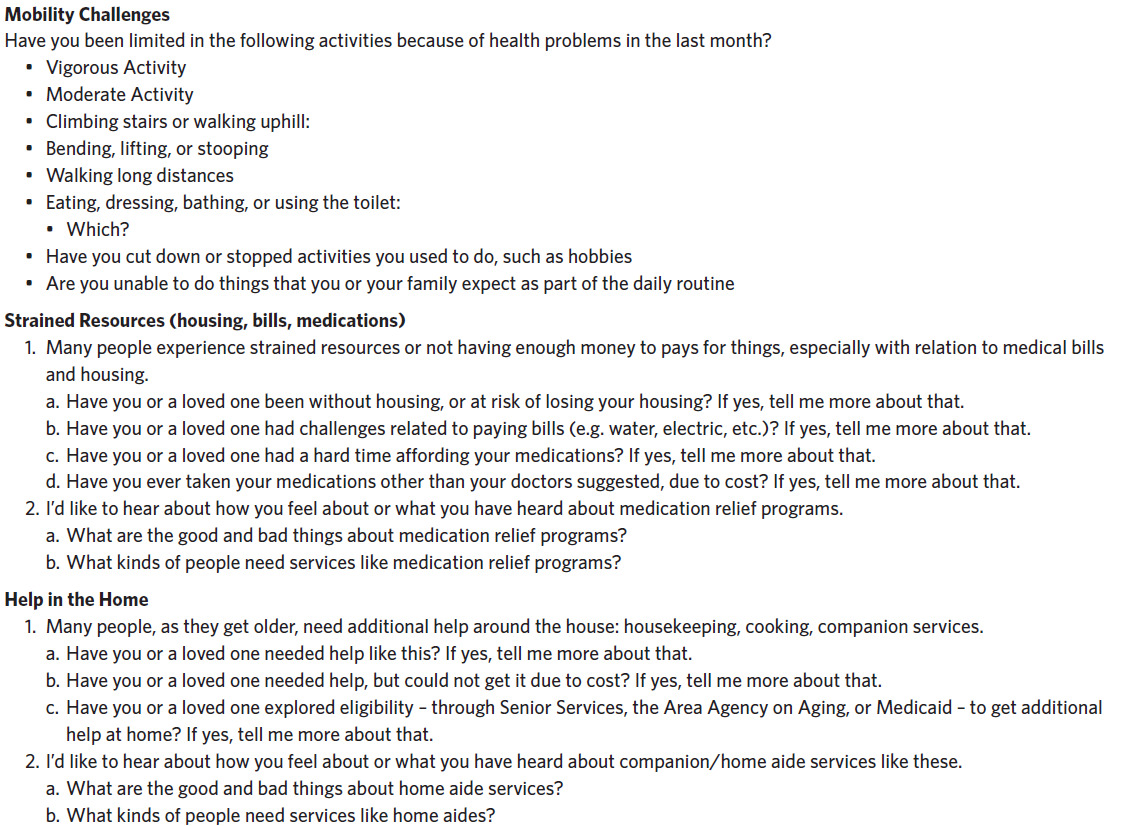

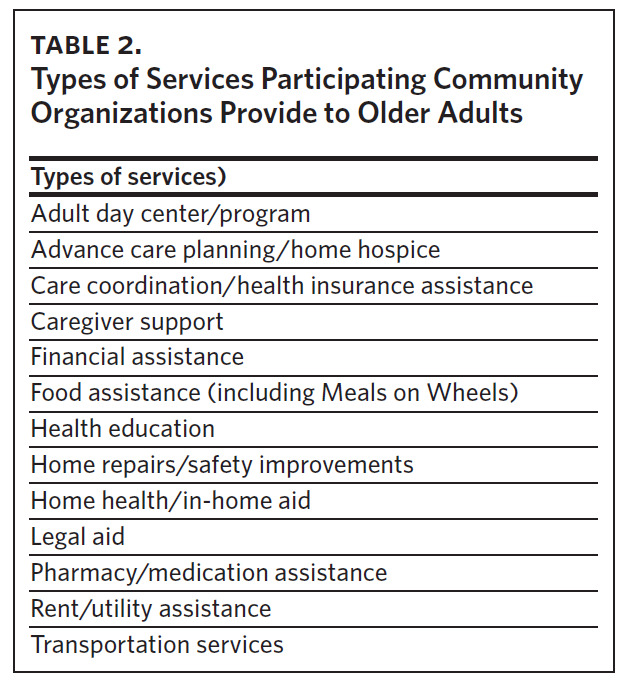

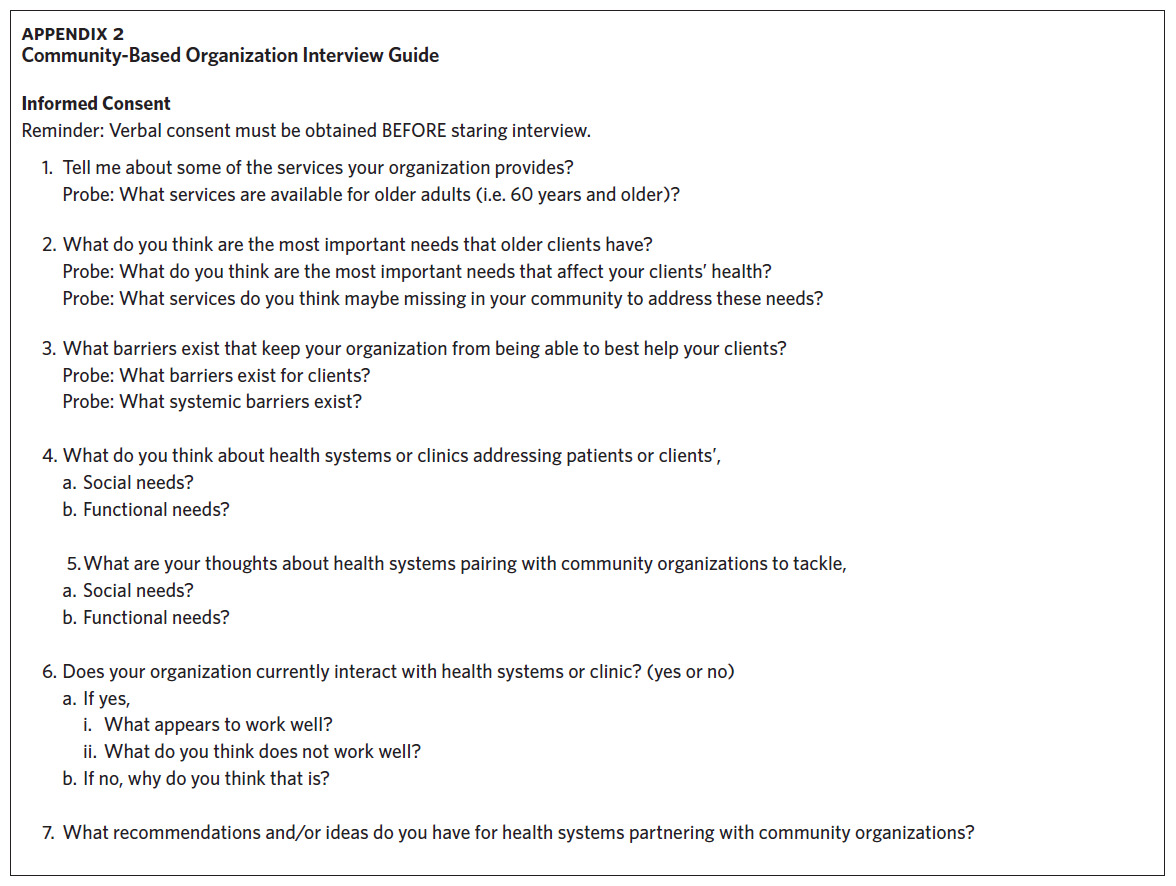

Through a detailed review of the literature, consultation with outside experts, and input from community organizations, we developed two interview guides. The patient interview guide (Appendix 1) was designed to elicit patients’ perceptions on the 1) social and functional needs they may be experiencing, 2) barriers to accessing resources, and 3) experiences with receiving support at home or through their health care providers. The community organization guide (Appendix 2) was designed to elicit participants’ perceptions of 1) the social and/or functional needs of the older adults the organization served, 2) the barriers/facilitators older adults may experience in accessing services, and 3) how community-based organizations and health systems could partner to assist older adults with these needs. The guides were pilot-tested for face validity with representative patients and community organization staff who were not included in the study.24 During the pilot-testing, patients and community organization staff could provide additional input on the interview guide questions.

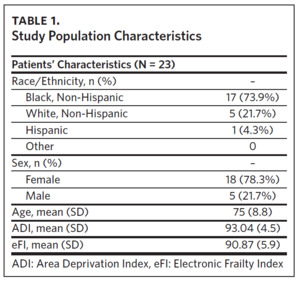

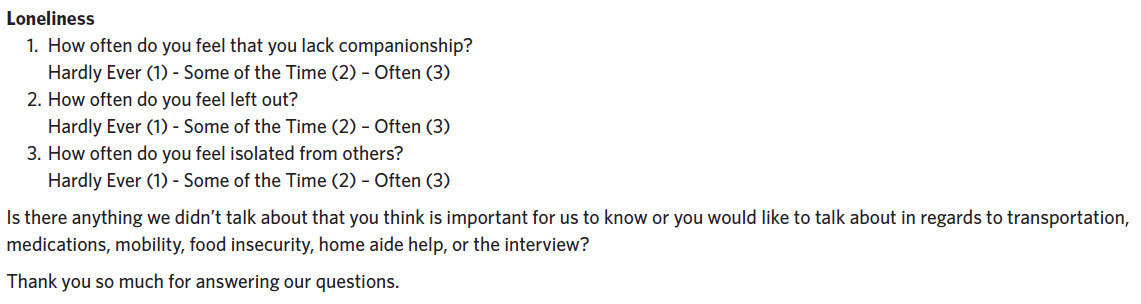

We conducted 23 interviews with patients and 28 interviews with staff between May 2021 and August 2021. All interviews were conducted by researchers (Haley Park and Corrinne Dunbar) trained in qualitative interview techniques. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. For patients, we collected age, gender, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, or other/ mixed race) through data extraction from the EHR.

Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and de-identified. We analyzed the patient and staff qualitative data in parallel. We imported the raw narrative data into QRS NVivo 12 (QRS International, Burlington, MA) to store, manage, and analyze the data. We used an inductive content analysis approach to code interviews, a technique that systematically describes qualitative data. Codes were created inductively as they emerged from the data. A coding scheme and dictionary were developed from the first five patient interviews and the first five staff interviews.24,25 We used the constant comparative method to evaluate and revise codes.26 Two researchers (Elena Wright and Deepak Palakshappa) coded each transcript independently and assigned codes to specific responses in each transcript based on the coding scheme.25 If the two reviewers did not agree, they discussed their perspectives and sought a consensus. Themes were iteratively identified. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was reached. We used triangulation with stakeholders in the community and in the health system to evaluate and establish the validity of the results.24,26

Results

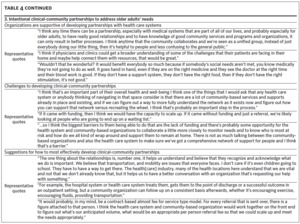

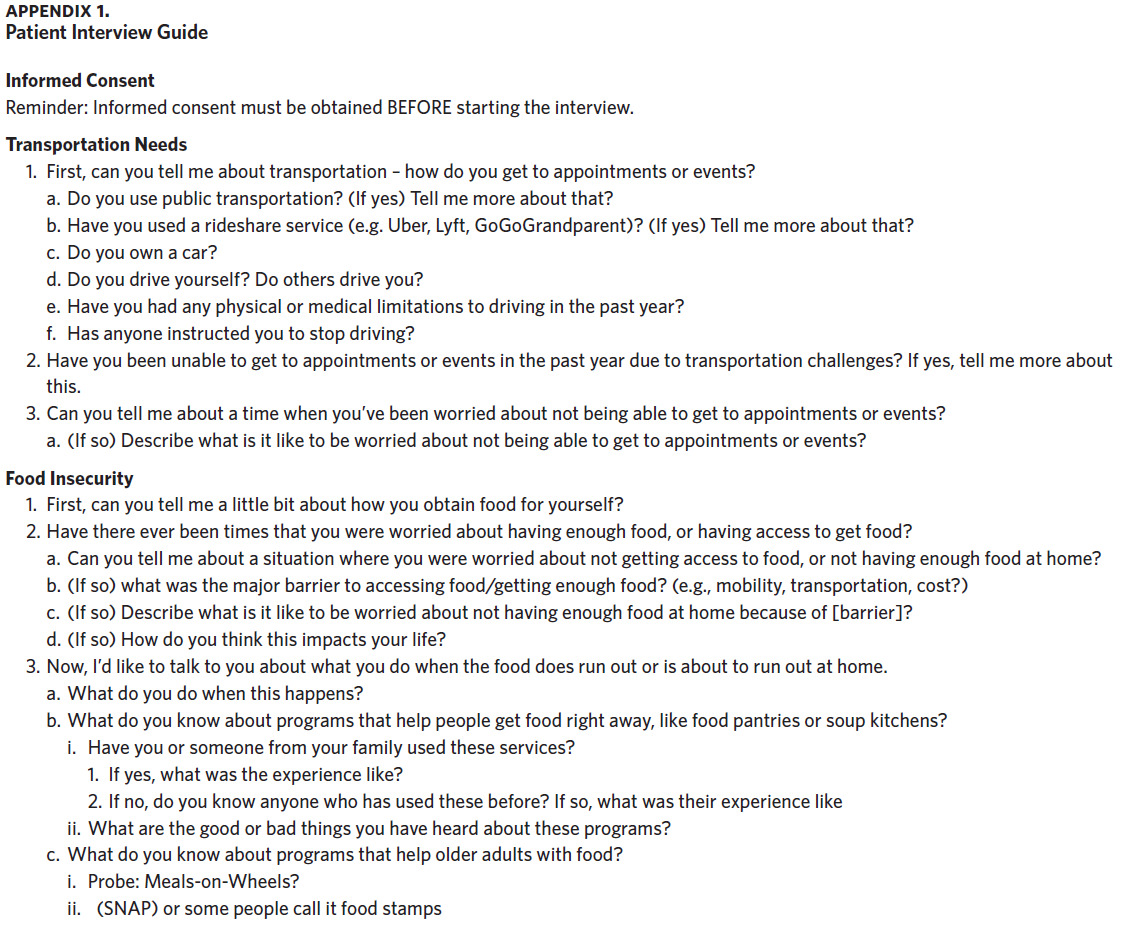

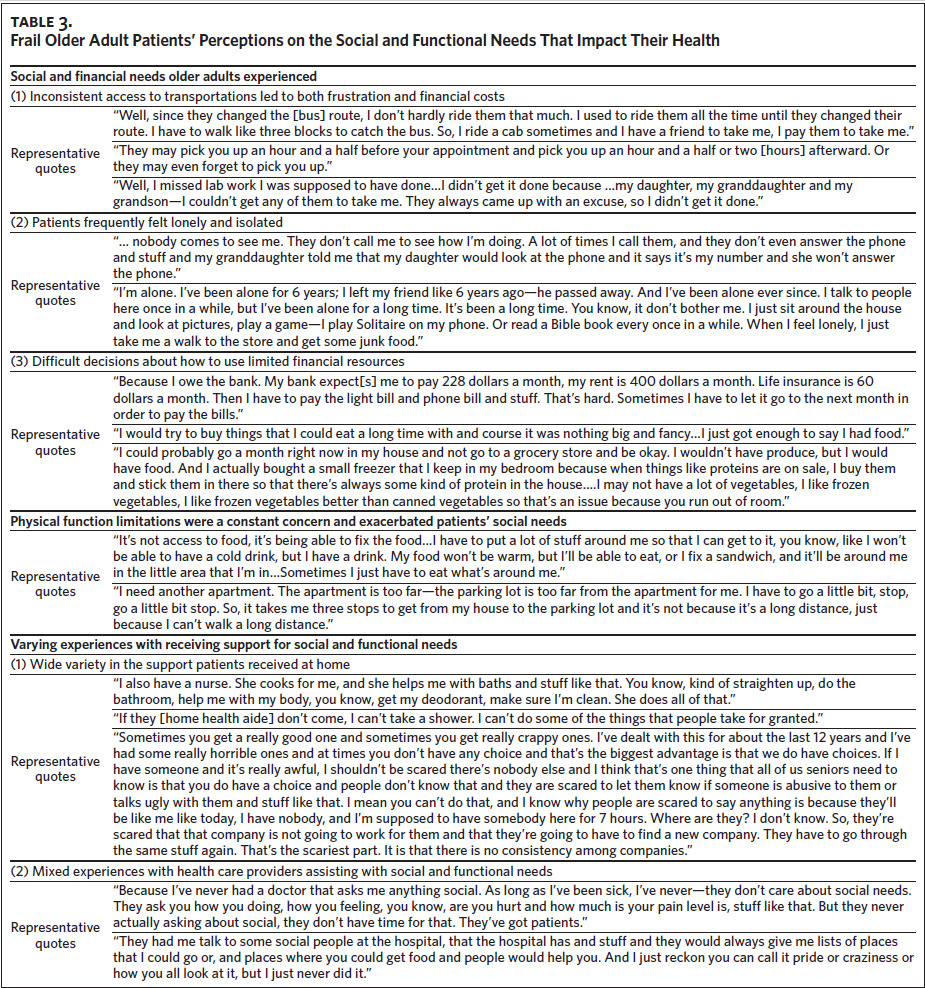

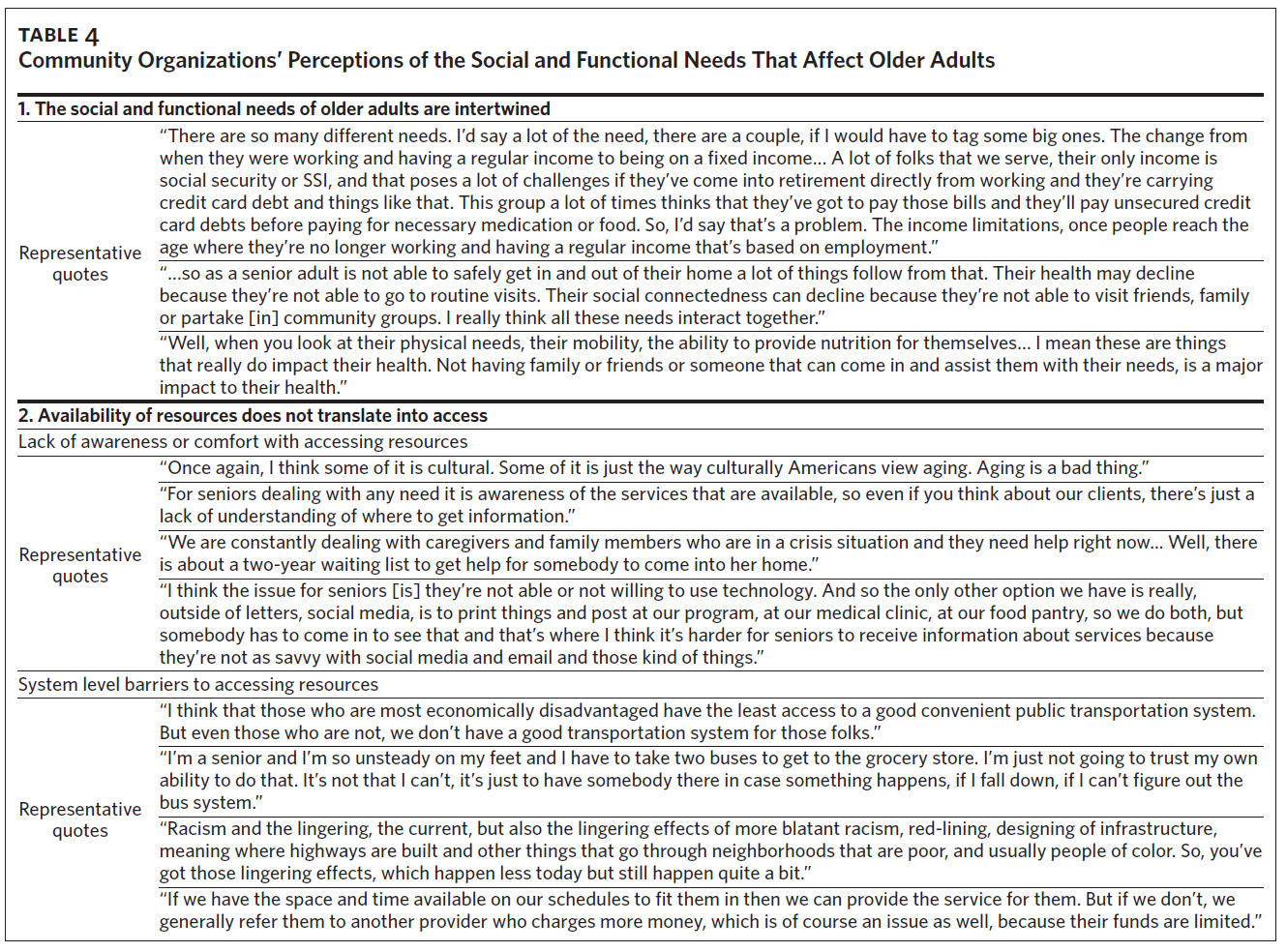

Of the 23 older adult patients who completed an interview, 17 were Black, 18 were female, and they had a mean age of 75 years (Table 1). Twenty-eight representatives from 22 organizations completed an interview (Table 2). We identified three primary themes with additional subthemes from the patient interviews and three primary themes with additional subthemes from the community organization interviews. We provide representative quotations for these themes below, with additional supporting quotations in Table 3 and Table 4.

Older Adults with Frailty

Theme 1: Social and Financial Needs Older Adults Experienced

Subtheme 1.1: Inconsistent access to transportation led to both frustration and financial costs. The most common social need reported was lack of transportation. This was due to being unable to afford transportation as well as limitations in being able to drive due to their health. Being reliant on others was not only frustrating but also incurred financial and time costs. Many patients paid friends or neighbors in order to attend medical appointments or complete routine tasks. One patient stated, “I pay people to take me to the grocery store and to the doctor.” Patients also emphasized that while they may qualify for transportation services (e.g., Medicaid TransAid), the lack of reliability of the services was challenging.

Subtheme 1.2: Patients frequently felt lonely and isolated. The majority also discussed feeling lonely and isolated. For some, this was because many of their family and friends had died. For others, this was due to their health or limitations in their mobility; as one patient discussed, “Most of the people that I talk to on the phone [are] disabled like I am, so I really don’t have friends [for] going out to dinner.”

Subtheme 1.3: Difficult decisions about how to use limited financial resources. Although some patients discussed having other unmet social needs (e.g., food insecurity), most discussed a constant juggling between competing demands due to limited financial resources. As one patient discussed, “I would run out of money sometimes during the week [and] you would kind of be…do I pay the hospital bill, food, or this, that, and the other.” Patients often used various strategies to try and meet their needs, such as alternating paying bills or stretching the food in the house.

Theme 2: Physical Function Limitations Were a Constant Concern and Exacerbated Patients’ Social Needs

Fifteen of the 23 patients discussed how their health and limitations to their physical function affected their daily lives. One patient reported, “If I fall, it would be hard for me to get back up. I stayed on the floor for like six hours one time.” These functional limitations often affected the foods patients were able to eat or the places they were able to go. As one patient mentioned, “I try to get into the kitchen, but I don’t try to cook now, because I’m scared [I’ll] fall.” Another participant reported, “I haven’t been anywhere that has a lot of steps; I have three steps going into my front door, but I don’t really do that much, I use the back and I have one step.”

Theme 3: Varying Experiences with Receiving Support for Social and Functional Needs.

Subtheme 3.1: Wide variety in the support patients received at home. Many patients did not have family and friends available. For patients who did, they often could rely on their family and friends to assist them with their needs. As one patient discussed, “My son. [He’ll] get [me] to the doctor’s office and he’ll get my groceries.” Some patients also had access to a home health aide who could assist with needs.

For most patients, however, a home aide was often insufficient, either due to patients not being able to afford home health services or only qualifying for a limited number of hours. Other patients said the quality of help was inconsistent and raised concerns about how aides would treat older adults. As one patient reported, “I had an aide, she stole our rent money, and we had to take out a loan to pay our bills that month.”

Subtheme 3.2: Mixed experiences with health care providers. When asked about discussing their social or functional needs with health care providers, patients had mixed experiences. Most reported that their health care providers did not ask them. A few felt health care providers were starting to ask, but patients felt it was important for providers to recognize that some patients may not want resources. As one patient stated, “My doctor wanted me to get [Meals on Wheels]…and I told her I didn’t want it… I’m not ready for that. As long as I can get $16 and just go buy me a whole chicken, I eat off of that for a week.”

Staff from Community-based Organizations

Theme 1: The Social and Functional Needs of Older Adults are Intertwined.

In almost all of the interviews, participants discussed how, for the older adults they worked with, social and functional needs were highly interconnected. Participants discussed how declines in clients’ physical function or cognition affected older adults’ ability to go shopping, prepare meals, and stay connected to friends and family.

Theme 2: Availability of Resources Does Not Translate Into Access.

Subtheme 2.1: Lack of awareness or comfort with accessing resources. Many participants felt that older adults and their families were often unaware of or did not feel comfortable accessing the resources available to them. Also, older adults or their families may be hesitant to learn about the resources available until the need becomes severe. As one participant stated, “Most people don’t know what’s available until they get into a crisis. You don’t want to find out about Meals on Wheels or home aide services or things like that if you don’t need it.”

Subtheme 2.2: System-level barriers to accessing resources. Most participants felt that transportation was a major barrier. Many older adults either could not afford their own vehicle or were not able to drive, and public transportation was a challenge to navigate. The other major barrier was limitations on what the organization could provide. One participant stated, “The first one is funding. It’s not for [the] food, it’s for the infrastructure—the funds needed to have the infrastructure to provide that assistance.”

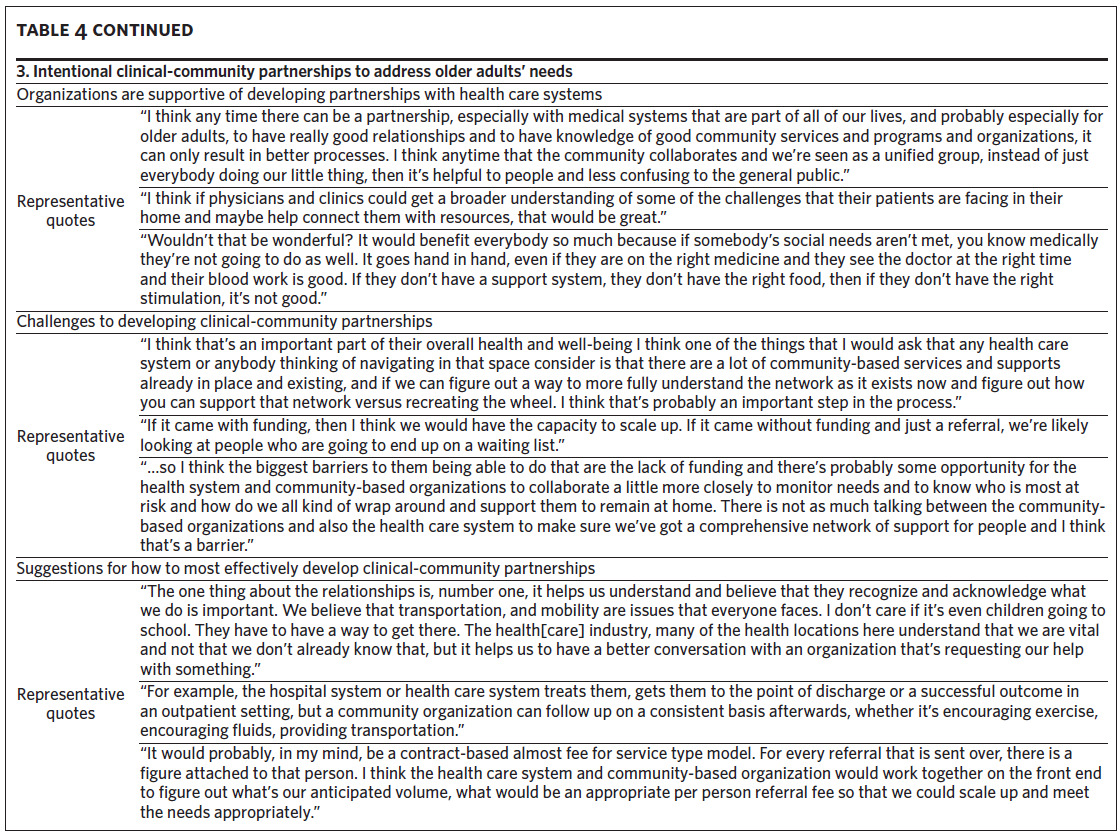

Theme 3: Intentional Clinical-Community Partnerships to Address Older Adults’ Needs.

Subtheme 3.1: Organizations are supportive of developing partnerships with health care systems. In almost all of the interviews, participants were very interested in developing partnerships with the health systems to address older adults’ needs. As one participant stated, “[I] think it would be wonderful if [health care providers] could do more of that, because older adults typically have a trusting relationship with their physician.”

Subtheme 3.2: Challenges to developing clinical-community partnerships. Even though most were excited about partnering with health systems, participants reported several potential challenges. First, many discussed how health systems should be aware of the services that organizations have been providing and avoid duplicating these services. Second, participants were worried about the potential increase in referrals. Many of the organizations had limited budgets and staff and were not sure if they would be able to handle a large increase in referrals.

Subtheme 3: Suggestions for how to most effectively develop clinical-community partnerships. Participants had several suggestions for how to effectively build partnerships. The most frequently cited suggestion was ensuring that the community organizations’ ideas and perspectives are included. As one participant stated, “It helps that we know that the organizations feel that we have a place at the table in terms of helping provide solutions.”

Discussion

Although research focusing on addressing social needs in health care settings has been growing,27,28 few studies have examined the unique needs of older adults with frailty and how to effectively develop clinical-community partnerships to address their needs. In this study, we evaluated frail older adult and community organization staff perspectives and found that social, financial, and functional needs were common and highly intertwined. Patients, clinicians, and policymakers should be aware that availability of community resources to assist older adults with those needs, however, does not translate into access, and the support older adults receive at home and from their health care providers varied.

Similar to prior studies,29,30 we found that a lack of transportation and social isolation were two of the most common social needs expressed by older adults. Inconsistent transportation not only led to feelings of frustration but also to a financial burden as patients frequently had to pay friends or neighbors to take them to the store or to medical appointments. Improving the public transportation infrastructure is important for addressing the lack of transportation. Federal regulations allow Medicaid to provide non-emergency medical transportation to beneficiaries, but patients who took advantage of this reported logistical difficulties such as challenges with scheduling and availability that may need to be improved. Given the increased recognition of the impact of transportation barriers on health, there have been a growing number of programs that use application-based rideshare programs to provide transportation to patients for nonemergency medical services, but the impact of the programs on health outcomes is still unclear. Lack of transportation also led to worsening feelings of loneliness,31 as many older adults discussed their only opportunities for interaction were on the phone or if others came to visit.

Although insufficient transportation and loneliness were the most common needs reported, participants also discussed concerns about facing competing demands (e.g., choosing between spending money on food or rent) that led to some having food insecurity or housing instability.

One unique challenge that we found in this study, compared to studies in other populations, is that the social and functional needs of older adults were intertwined.3,32 For older adults, limitations to their physical function or declines in their cognition could lead to unmet social needs (e.g., not being able to consistently access food), but also, financial limitations could exacerbate their functional needs (e.g., by impacting their ability to pay for medical care).32 Health systems that are interested in addressing the unmet social needs of older adults, particularly those who are frail, should consider utilizing interventions (e.g., home delivery) that address both the financial and functional needs of older patients.15,27,28,33

As in other studies,34–36 community organizations were open to partnering with health systems. The majority of patients, though, reported that their health care providers did not routinely discuss social and functional needs. The implementation of social risk screening tools in health care settings has increased and could be one strategy to identify patients.11,12,37 A growing number of national organziations are recommending, and in the future will require, that health systems screen patients for social risks,7–13 and Epic includes a social risk screening tool that collects data as discreet data fields. Although many individuals could benefit from social risk screening, providers and policymakers should recognize that not all patients may be responsive. Several studies have found that even when patients are identified as having social risks, they may not see it as a need and decline assistance.15,31 We observed many patients describing assistance as something they’re “not ready for.” One reason frail older adults could decline resources may include concerns about maintaining their independence or losing their dignity by accepting help.38 One issue that community organizations felt was unique to older adults, and that patients and health care providers should be aware of, was that patients and families only became aware of resources when they or their family members sought help in a “crisis.” Families were often in need of urgent resources, but because of limited infrastructure, staff, or funding, organizations were not able to provide these services immediately.39 A major challenge to integrating social and functional-care interventions may be implementing these strategies in a patient-centered approach that respects the wishes of patients but also accounts for some of the systemic barriers in obtaining community resources. Unless public policy changes occur to strengthen the social safety net, implementing screening may have to not only be an approach to connect older adults who are interested in services but an opportunity to educate patients and their families about the wait times to receive resources and anticipate future needs. Being intentional and ensuring that community organizations are equal partners in developing clinical-community partnerships could help these efforts.

Although this study has many strengths, such as including a high proportion of Black North Carolinians and an older adult cohort, there are several limitations to our study that should be acknowledged. First, while our study reached saturation with qualitative themes, our sample was limited to patients and community organizations from one county in North Carolina, and the results may not be generalizable to other areas. Additionally, our sample was not large enough to determine if themes varied by particular patient characteristics (e.g., gender or race/ethnicity), which could be an area for future research. Second, we only interviewed patients who were identified as having frailty, and it is important to recognize that older adults who do not have frailty may have different perceptions. Third, all of the interviews occurred during the summer of 2021. Many of the COVID-19 pandemic era policies, such as increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Benefits, that were in place at the time have ended. Participants’ perspectives on the need and availability of services may have changed. Finally, we focused on the perspectives of patients and community-based organizations. Further research is needed to evaluate health care providers’ perspectives.

Conclusion

In this qualitative study that combines the perspectives of patients and community organizations, we found that the social and functional needs of older adults are highly intertwined. Our findings indicate the need to support the frail older adult population in multifaceted ways. Future studies will need to determine how to most effectively design and implement social and functional care interventions that comprehensively support older adults’ health and include purposeful collaborations between health systems and community-based organizations.

Acknowledgments

All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors. Dr. Callahan is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the NIH under Award Number K76AG059986. Dr. Gabbard is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG070234. Dr. Palakshappa is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL146902. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding sources did not have any role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. DP reports personal fees from WellCare of North Carolina outside of the submitted work. Portions of this study were presented at the American Geriatric Society Meeting in May 2022.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.