Adequate prenatal care (PNC) is associated with a decreased risk of both maternal and fetal adverse outcomes.1–4 It generally consists of a comprehensive list of screenings and examinations starting in the first trimester and increasing in frequency as pregnancy progresses. PNC provides surveillance and management of various risk factors during pregnancy, including hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disease, and clotting disorders, while maintaining a focus on preventive care, including diet, exercise, and overall well-being.1,2,5 Adequate PNC decreases the risk of fetal adverse events, including preterm birth, vertically transmitted infections, and infant death; it also allows for the early diagnosis of maternal conditions such as chronic hypertension and placenta accreta spectrum disorder.1–4 Obstetric care further provides benefits in the postpartum period, exhibited by increased confidence in newborn care and the treatment of postpartum depression or psychosis.6–8

Typical PNC, as defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), includes an initial PNC visit plus visits

every 4 weeks until week 28, visits once every 2 weeks until week 36, and weekly visits between 36 weeks and delivery.5 This recommendation is made for average-risk pregnancies, and it should be noted that high-risk pregnancies may require additional visits for adequate care.

Previous studies have elucidated that race, income, and education level are associated with a lower receipt of PNC, with minorities and those of low socioeconomic status (SES) facing increased barriers to care.3,9–11 Reported barriers include transportation, child care, finances, and a lack of social support.9–13 Additionally, the lack of cultural sensitivity exhibited by providers has been shown to present significant

barriers to minority individuals. Such barriers may include a lack of interpretative services and associated long wait times or undocumented status interfering with health insurance eligibility.12,13

As of 2020, 17.2% of live births in North Carolina were born to women who received inadequate PNC, with the highest rates seen among Black, Hispanic, and Native American

women.14 As rates of maternal morbidity and mortality remain disproportionately high for Black mothers, increasing the rate of adequate PNC serves as a vital risk-reduction strategy.

This study aimed to identify barriers to PNC that pregnant individuals face and to assess rates of PNC receipt. To address these aims, we surveyed individuals admitted to the Birth Center at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (AHWFB) Hospital regarding demographic data, frequency of PNC visits, and reported barriers to care. This study was designed to test the following hypotheses: 1) relative to non-Hispanic White individuals, individuals who identify as being from historically marginalized racial or ethnic backgrounds, such as non-White race or Hispanic ethnicity, experience more barriers to care and are less likely to receive adequate PNC; 2) relative to individuals whose household income exceeds $20,000 per year, individuals who report annual household incomes below $20,000 will experience more barriers to care and will be less likely to receive adequate PNC; 3) increased barriers to care are associated with lower rates of PNC. Secondarily, we sought to explore the independent association of income and adequate PNC, as well as the interaction of income with race/ethnicity and the receipt of adequate PNC.

The benefits of identifying local barriers to care, as well as understanding the association between these barriers and social determinants of health, may guide future efforts to develop interventions that fill the care gap and increase rates of PNC compliance in the community.

Methods

Participants

From May 16, 2021, through July 2, 2021, 200 participants (of 213 individuals approached) consented to participate in this study. The Epic Electronic Medical Record (EMR) was used to identify individuals eligible for study participation. Eligibility included individuals who were English- or Spanish-speaking, aged 18 years or older, and were 35 weeks pregnant or more at delivery. Hospital interpretation services via Stratus video or in-person interpretation were used in the recruitment and participation of Spanish-speaking individuals. A convenience sampling approach was used to identify and enroll patients either prior to labor induction or in the postpartum setting prior to discharge. Verbal consent was obtained prior to study participation. IRB approval was granted prior to study initiation (IRB00073747). Participants received a thank you note and a pair of newborn socks valued at less than $5.00.

Measures

Participants were administered a 14-question paper survey that was completed in privacy. The survey collected nonidentifiable demographic information including age, race,

ethnicity, family size, and income. Individuals had the option to forego disclosure of more sensitive questions regarding income, race, and ethnicity. Socioeconomic status (SES) was

approximated by household income reported in increments of $20,000 annually. These increments were created to allow for the approximation of the sum of income generated by all family members in a household. Lower SES was defined as an annual family income of less than $20,000, which would place them below the federal poverty line regardless of family size. Additional information collected included the frequency of PNC visits and barriers to receiving PNC. Prenatal care was assessed across 3 intervals, defined as less than 28 weeks, 28–36 weeks, and greater than or equal to 36 weeks gestation in accordance with the ACOG recommendations.5 Surveys were available in English and Spanish, and an interpreter was made available for Spanish-speaking participants. The team verified that all survey items were completed or purposely omitted before entering the survey data into REDCap, where all data were housed, and each survey was assigned a record ID.

Analysis

The primary outcomes of this study included the determination of PNC receipt rates and the identification of PNC barriers. Adequate PNC was calculated according to the ACOG PNC standards, defined as having received an initial PNC visit plus visits every 4 weeks through 28 weeks gestation, every 2 weeks from 28 to 36 weeks gestation, then weekly until delivery.5 Due to the low numbers of Black/African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander individuals, racial stratification of non-Hispanic White versus non-White or Hispanic participants was performed. An additional stratification was made between low household income (defined as less than $20,000 per year) versus household income greater than or equal to $20,000 per year. We determined the overall frequency of reported barriers to care and assessed the prevalence of barriers based on the same stratifications.

Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics for categorical data. The Pearson chi-square method was utilized to draw comparisons between demographic groups receiving adequate or inadequate PNC, and between groups reporting barriers to care. Using the chi-square method allowed inferences to be made regarding compliance and barrier reporting between defined demographic groups. Finally, a series of logistic regressions were conducted to determine if observed effects persisted after controlling for age and income. Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses and power calculations.

Results

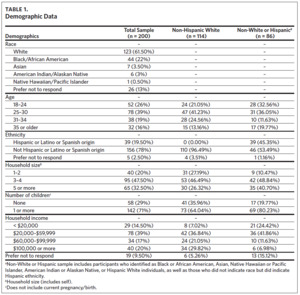

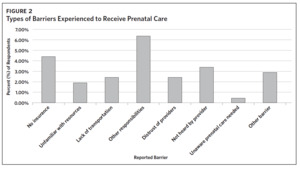

Of the 213 people invited to participate in the study, 200 participants completed the survey, with 16 surveys completed in Spanish. Demographic data were collected for all

study participants (Table 1). The analytical sample included 114 non-Hispanic White individuals, 51 individuals who identified as a race other than White, and 26 not reporting

race. The 26 participants (13%) who chose not to disclose information pertaining to race all identified as Hispanic. Due to the variety of races reported and the small number per group, these participants were recorded under a “non-White or Hispanic” category. The non-White or Hispanic designation included Black or African American, Asian, Native

Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Hispanic White individuals, as well as those who did not indicate race but did indicate Hispanic ethnicity.

Notably, 7 individuals indicated that they identified with 2 races. Most participants were between the ages of 25 and 30 (39%), with 71% reporting 1 or more previous children.

Of the participants, 16% of individuals (n = 32) were of advanced maternal age, defined as being greater than or equal to age 35.

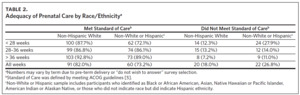

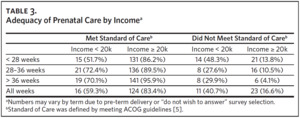

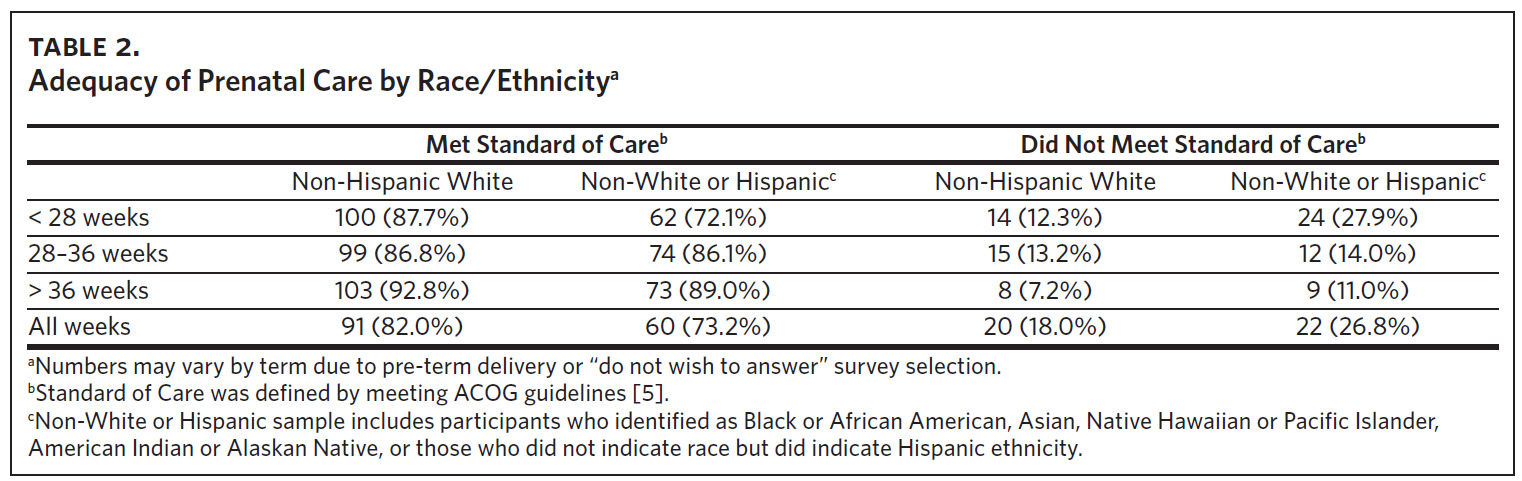

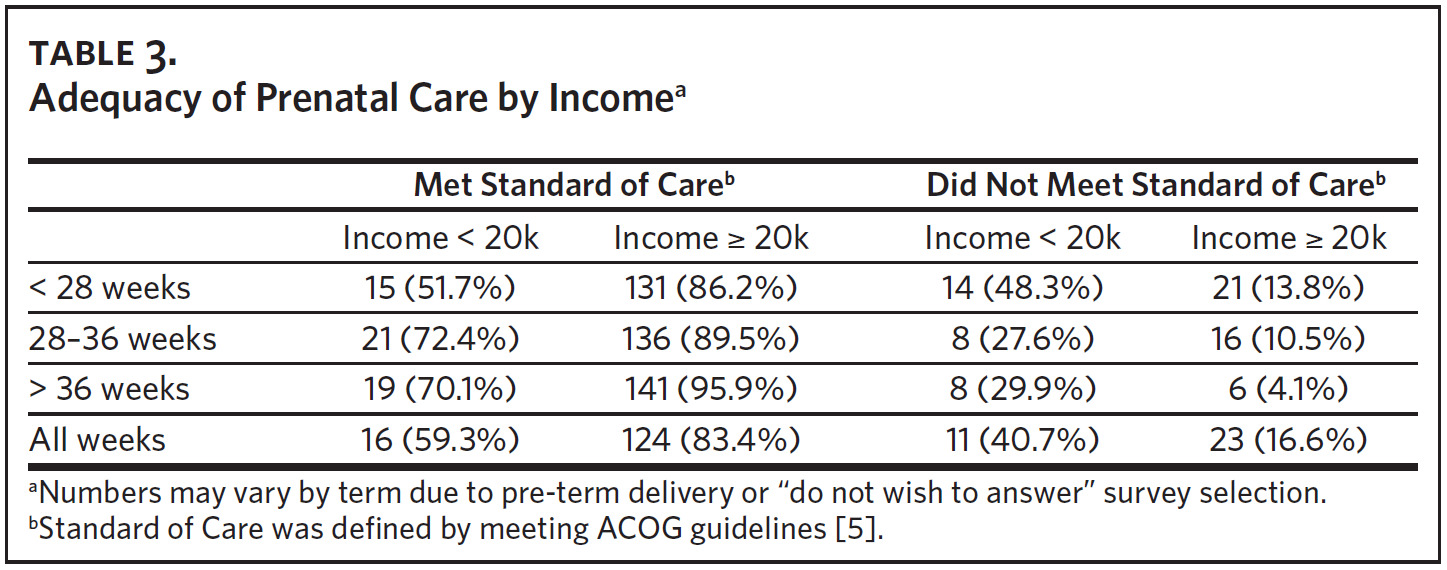

The overall PNC receipt rate was 81% in the first 28 weeks, 87% between 28 and 36 weeks, and 88% after 36 weeks gestation. A total of 76% of individuals reported adequate PNC at all 3 time periods. The rate of adequate PNC among non-White or Hispanic individuals in the first 28 weeks of pregnancy was 72%, which was significantly lower than the rate of 88% reported by non-Hispanic White individuals (X2 = 7.78; P < .02). However, there were no significant differences in PNC rates between non-Hispanic White and non-White or Hispanic individuals after 28 weeks of pregnancy (Table 2). It was found that participants who reported an annual family income of less than $20,000 were less likely to receive PNC up to 28 weeks (X2 = 18.5; P < .01), from 28–36 weeks (X2 = 6.2; P < .05), and from 36 weeks to delivery (X2 = 2.1; P < .01) (Table 3).

Logistic regression analyses were performed separately for each of the 3 designated time periods for PNC in 2 separate models. The first model included age and the non-Hispanic White categorization. The results of the first, unadjusted model were consistent with the chi-square analyses, with race/ethnicity being a significant predictor of adequate PNC in the first 28 weeks, X2 (2, N = 200) = 7.81, P < .01, but not after 28 weeks gestation. In the second model that included age, race/ethnicity, income, and a race/ethnicity by income interaction term, the relationship between race/ethnicity and PNC was non-significant in all 3 time periods. However, income was a significant predictor of adequate PNC (P < .01) during the first 28 weeks, X2 (4, N = 181) = 18.02, P < .01, and after 36 weeks, X2 (4, N = 174) = 15.25, P < .01, but not between 28–36 weeks. The interaction term was non-significant at any timepoint.

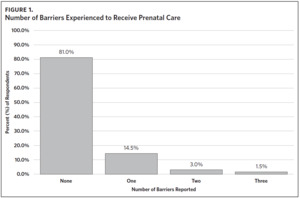

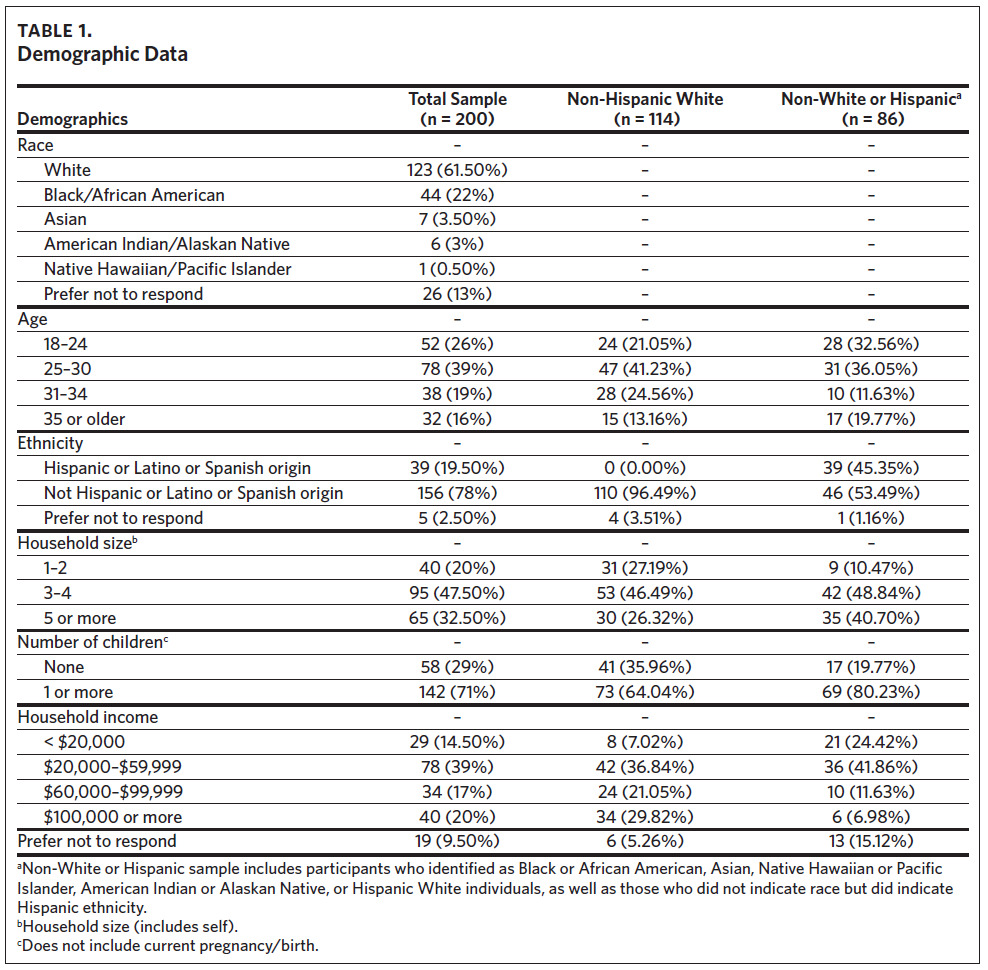

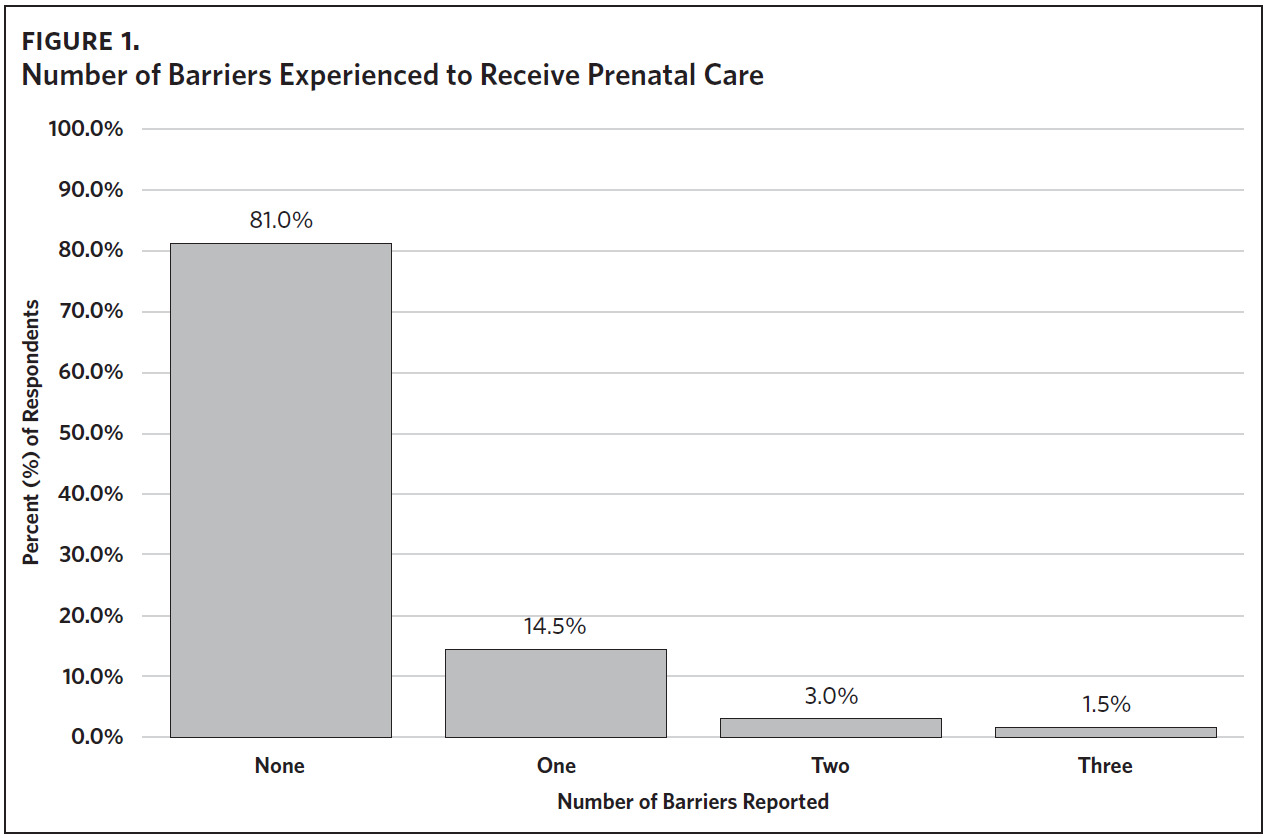

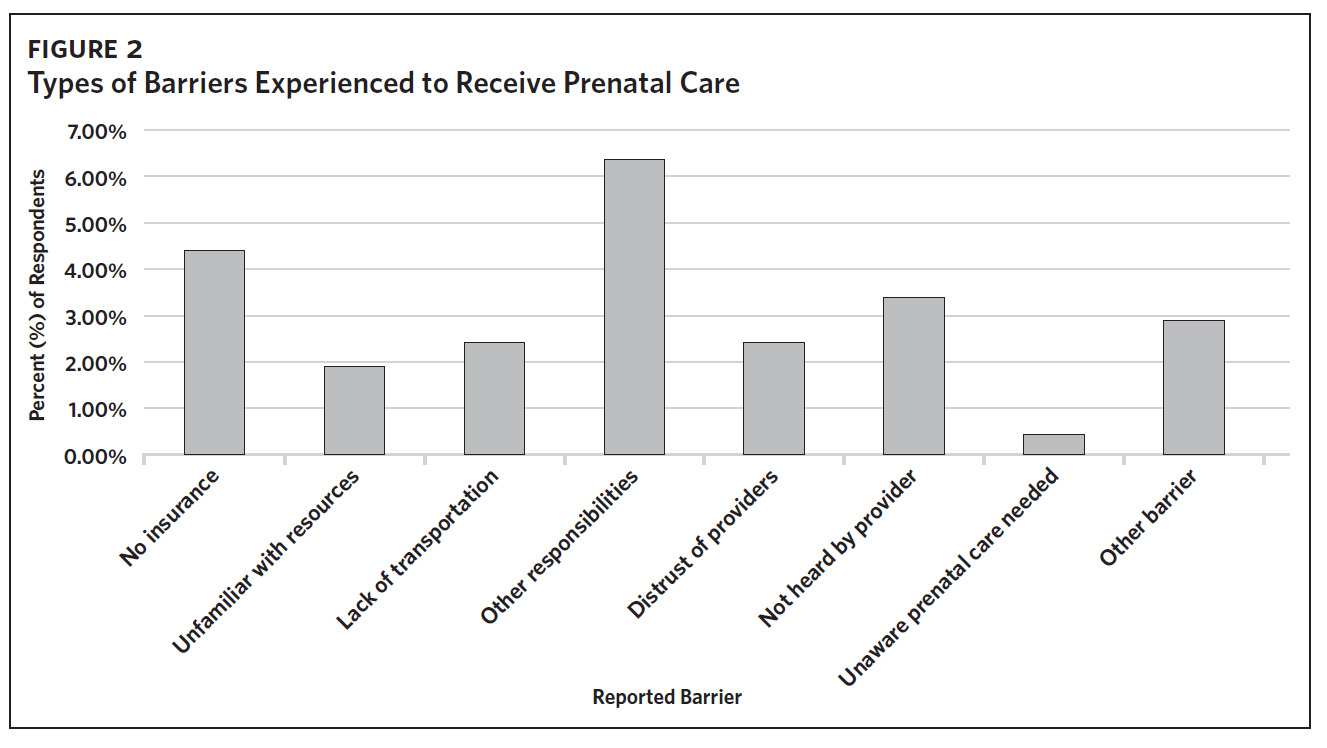

In terms of barriers to care, 19% of individuals (n = 38) reported at least 1 barrier, while 4.5% (n = 9) reported 2 or more barriers (Figure 1). The most reported barrier was

“other responsibilities” related to child care or work (6.5%), with “lack of insurance” being the second most common barrier reported (4.5%) (Figure 2). Regarding barriers to care as

they relate to the patient-physician relationship, 2.5% of the individuals reported “distrust of medical professionals,” and 3.5% reported “not feeling heard by their provider.” These

barriers, which collectively represent apprehension to medical care, were observed in 6.0% of the respondents. There were no significant differences in reported barriers between

non-Hispanic White versus non-White or Hispanic individuals, or according to annual household income. However, it was found that participants who reported at least 1 barrier

were less likely to receive PNC up to 28 weeks (X2 = 12.8; P < .01), from 28–36 weeks (X2 = 4.2; P < .05), and from 36 weeks to delivery (X2 = 6.2; P < .05).

Discussion

This study observed disparities in PNC receipt based on race, ethnicity, and income. It demonstrated that non- Hispanic White individuals were more likely to receive PNC during the first 28 weeks of pregnancy than non-White or Hispanic individuals. These findings are consistent with prior studies that have shown lower rates of PNC for Black and Hispanic mothers as compared to White mothers.15 It is also in line with 2019–2021 March of Dimes data in North Carolina, which showed that 24.5% of Hispanic and 21.6% of Black women received inadequate PNC compared to only 12.7% of White women.16 We believe these differences are in large part due to inequities rooted in institutionalized and systemic racism that still exist against Black and Brown people today. This is not a novel revelation, as much of the literature acknowledges the presence of racism in our health

system and the detrimental effects it imposes on maternal and infant health.17–20 As such, we must focus on closing these care gaps and finding effective ways at the institution and policy levels to combat racist practices, such as through efforts to improve racial concordance amongst health care providers and leadership. Furthermore, we should incorporate the scholarship, expertise, and lived experiences of Black and Brown advocates in this realm when reforming health policy.21

Additionally, our study identified that individuals with household incomes of less than $20,000 were less likely to receive PNC throughout pregnancy. Using household

income as a relative indicator of SES, our results closely align with previous studies that have demonstrated low SES as a barrier to adequate PNC.22–24 These disparities are

alarming considering that delayed PNC is associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.25,26 Furthermore, they suggest a need for assistance and programs focused on the early initiation of first-trimester PNC for non-White or Hispanic individuals in the Forsyth County community. Proposed policy solutions to mitigate these

disparities in PNC include Medicaid expansion, increased access to midwifery care, and insurance coverage of telehealth services.27

The most reported barrier to care in our study was responsibility related to child care and work. This aligns with prior literature that has demonstrated barriers to care associated

with the inherent responsibilities of having other children, such as financial demands and difficulties obtaining reliable child care.13,22,28,29 Additionally, it is important to note that many participants were also affected by COVID-19 pandemic-related daycare and school closures which further exacerbated child care demands. Some reports have even shown that mothers with children were more likely to face job and income losses during the pandemic than those without children.30 Interventions, such as clinics providing child care or home visits, could help to mitigate this barrier.31

The second most common barrier reported in our study was lack of insurance, which has historically been recognized as a major barrier to PNC.28,29,32 Insurance barriers have also been shown to affect continuity of care, as several patients have struggled to find a clinic that keeps a consistent Medicaid policy.23 Marín and colleagues

reported a notable difference in PNC receipt between 58.7% of uninsured mothers initiating care during the first trimester versus 83.1% of privately insured mothers.33

Immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, stand at the center of this issue. Eligibility rules for Medicaid for Pregnant Women (MPW) in North Carolina require beneficiaries to be a citizen or a qualified non-citizen.34 The same individuals who are ineligible for MPW are also ineligible to purchase insurance through the Affordable Care Act

Marketplace, leaving them with only emergency delivery coverage through the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act of 1986.35 This is in contrast to states like New York, where regardless of immigration status, pregnant women may qualify for free prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care as long as they meet other requirements.36 Another prominent care barrier in our study was difficulties surrounding transportation. Several studies have recognized transportation as an obstacle to receiving proper continuity of care.22,23,32 The lack of reliability of various forms of transportation, such as public transit systems, has been shown to result in patients arriving late to their appointments and potentially forcing them to reschedule due to clinic-specific protocols.28 Of note, ride services and vouchers were deemed in multiple studies to be a notable

facilitator in helping patients overcome transportation barriers.29,32

Multiple individuals in our study reported barriers directly related to their relationship with medical professionals, citing either distrust of their provider or feeling that

their concerns went unheard by their provider. In fact, this study is one of several demonstrating apprehension to PNC due to apparent gaps in patient-provider communication.10–13,22,23,29,37 Within current literature, women report that provider distrust is often due to a lack of patient-centered dialogue, feeling excluded from medical decision making, and poor communication styles.29–33,37 Recognition of these elements by providers and incorporation of the shared decision-making model may help to reduce this barrier.37,38

This study was strengthened by its high participation rate, which minimized participation bias and allowed for a representative study. Additional strengths included cost-effectiveness and versatility, allowing for the creation of a succinct survey that minimized participation time. However, the results of this study must be considered in light of several limitations. The survey required participants to retrospectively quantify the number of PNC visits they received, and these responses were not verified by medical records, thus subjecting the study to recall bias. In an effort to mitigate this bias, PNC compliance was defined as having received PNC at a frequency equal to or greater than ACOG recommendations.5 This contrasts with the utilization of the Kotelchuck index, which requires reporting of visits on a monthly basis.39 As an accurate monthly account of PNC visits was deemed infeasible, the Kotelchuck index was not utilized. Lastly, as a convenience sample obtained from an academic medical center, our results may not be generalizable to other communities. Nevertheless, this study provides important insight regarding disparities of PNC receipt by race, ethnicity, and income present in the Forsyth County community. Additionally, offering the survey in Spanish expanded the participant pool and allowed for the reporting of barriers experienced by Spanish-speaking individuals.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the PNC compliance rate and barriers to PNC among 200 individuals receiving child care services at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Hospital from May 2021 through July 2021. Approximately 1 in 5 individuals (19%) reported at least one barrier to PNC, with “other responsibilities” such as child care and work serving as the most common barrier. There were no differences in the number of barriers reported based on an individual’s race, ethnicity, or income. Despite this finding, non-Hispanic White individuals were more likely to receive adequate PNC in the first 28 weeks of pregnancy than their non-White or Hispanic counterparts. Persons with estimated annual household

incomes of less than $20,000 were also less likely to receive PNC throughout their pregnancies.

These findings suggest that although race, ethnicity, and income did not play a role in the perception of barriers experienced, they did impact the likelihood of receiving adequate PNC. It is important to acknowledge how structural racism plays a role in a patient’s experience navigating such barriers, and how it in part explains many of the relevant health disparities. All in all, this study indicates that future programs aiming to increase PNC receipt should direct their support toward individuals of low SES throughout their pregnancies as well as non-White or Hispanic individuals, particularly in the first 28 weeks of pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Birth Center for their faculty support in participant recruitment and study administration. Morgan Yapundich and Rachel S. Jeffries are co-first authors, and both authors contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure of interests

The authors declare no relevant or financial interest related to the research study.

Financial support

No external funding was provided.