Introduction

Chronic pain is a critical public health issue in the United States. An estimated 20% of adults in the United States live with chronic pain.1 Those with chronic pain often turn to the health care system for treatment and other pain management strategies, but numerous barriers to health care access, such as cost and lack of insurance, can make this difficult, if not impossible.2 Individuals facing such barriers may use different coping mechanisms that do not require a health care visit, like over-the-counter medications, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs.

Notably, there are differences in both the prevalence of chronic pain and barriers to health care access by demographics such as race/ethnicity and sex, with women having a higher prevalence of chronic pain than men, and Black, non-Hispanic individuals experiencing more barriers to health care access than White, non-Hispanic individuals, for example.3 Understanding potential differences in chronic pain coping mechanisms by underlying health care barriers and demographics is critical to tailoring interventions and policies focused on supporting equitable access to appropriate care and treatment.

Using population-representative data, we estimated the prevalence of coping mechanisms among adults with chronic pain in North Carolina and examined how these coping mechanisms differed by specific health care barriers, sex, and race/ethnicity. Given unique health care systems and policies (e.g., marijuana legalization) across states, we focused on one state (North Carolina) where marijuana has yet to be legalized for medical or recreational use. This analysis can provide a framework for other states to consider in their efforts to support adults with chronic pain. Additionally, the descriptive and foundational nature of this analysis can inform action to mitigate potential health care barriers experienced by adults with chronic pain and aligns with recent efforts to elevate the value of descriptive epidemiology for addressing public health challenges.4

Methods

We analyzed pooled data from the 2018 and 2019 North Carolina Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (NC BRFSS) surveys. The NC BRFSS is an annual, population-representative survey generated from a probability sample of non-institutionalized North Carolina adults, administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Detailed methods are described elsewhere.5 We combined 2018 and 2019 data to calculate average proportions by adjusting the weight variables proportionally by yearly sample size, as recommended by the data documentation.6

In the 2018 and 2019 BRFSS surveys, North Carolina elected to include several state-added questions, including a chronic pain module, which a representative sample population was asked to complete. We identified individuals with chronic pain as those who responded “yes” to the question, “Do you suffer from any type of chronic pain, that is pain that occurs constantly or flares up often?” For those reporting chronic pain, we examined the frequency, severity, and cause. Frequency was measured using responses to the question, “About how often do you experience this pain?” where respondents could choose from 5 set options, ranging from “It’s constant, always there” to “Less often [than once a month].” Severity was measured on a scale from 0 to 10, where “0 means no pain at all and 10 means the worst pain you can imagine” with the question “How severe has your pain usually been over the past 3 months?” Respondents were also asked about the main cause of their chronic pain with no predefined categories.

Individuals who reported chronic pain were asked whether they are “doing anything to cope with [their] chronic pain?” [yes/no]. Among those who reported doing something to cope with their pain, respondents were asked whether or not they used the following 9 mechanisms [yes/no]: 1) “over-the-counter medication like ibuprofen or aspirin,” 2) “a prescription anti-inflammatory like Celebrex,” 3) "a prescription narcotic pain reliever like Percocet or Vicodin,"4) “some other prescription drug,” 5) “a non-medication pain therapy like acupuncture, physical therapy, or yoga,” 6) “alcohol,” 7) “marijuana,” 8) “a street drug other than marijuana,” and 9) “something else.” For our analyses, we combined the categories above into 5 coping mechanisms: over-the-counter medication (answer choice 1), any prescription medication (answer choices 2, 3, and 4 combined), non-medication pain therapy (answer choice 5), alcohol (answer choice 6), and marijuana or other street drugs (answer choices 7 and 8 combined).

We assessed 4 health care access barriers. We considered individuals to have a coverage barrier if they did not report any kind of health care insurance. If individuals lacked at least one person they thought of as their personal doctor or provider, we considered them to report a provider barrier. We considered individuals who indicated that there was a time in the past 12 months when they needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost to report a cost barrier. Finally, we considered individuals to report a checkup barrier if they reported having their last routine checkup more than 2 years prior or never.

We examined coping mechanisms by barrier type among those with chronic pain. We also examined coping mechanisms among those with no barriers and those with one or more barriers, stratified by race/ethnicity and sex. Race and ethnicity are separately measured in the NC BRFSS. Participants were asked to self-classify their race and ethnicity. Race and ethnicity were combined into one variable for analysis, utilizing a combined race/ethnicity measure provided by the BRFSS. Race/ethnicity subgroup analyses were restricted to White, non-Hispanic and Black, non-Hispanic individuals due to well-documented disparities in health care access between these 2 groups, to avoid the use of uninformative, heterogenous categorizations, and due to sample size considerations; the other racial/ethnic categories represented at most 3% of the weighted sample, resulting in very small, unweighted frequencies. We calculated unweighted frequencies and weighted percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The recommended BRFSS weighting methodology was used for all prevalence estimates to reduce bias resulting from differing probabilities of selection.6 Consistent with best practice statistical guidance, we examined the magnitude and precision of estimates to discuss potential differences between groups.7,8 All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was considered exempt by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

In total, 31.0% (95% CI: 29.7, 32.3) of North Carolina adults experienced chronic pain in 2018–2019. Of those with chronic pain (n = 2225), 58.7% (95% CI: 56.2, 61.3) were women, 71.1% (95% CI: 68.8, 73.5) were White, non-Hispanic, and 20.0% (95% CI: 17.9, 22.1) were Black, non-Hispanic (Table 1). Most reported experiencing chronic pain constantly (52.7%; 95% CI: 50.1, 55.3) and had talked to a health professional about their pain (90.8%; 95% CI: 89.2, 92.3) (Table 2). When ranking their pain 1–10, the median score was 5.5 (SE: 0.1). The most named cause of pain was arthritis (29.8%; 95% CI: 27.5, 32.1), followed by an accident or injury (13.3%; 95% CI: 11.5, 15.1) and sciatic, slipped disk, or spondylosis (12.4%; 95% CI: 10.7, 14.1). Most individuals (n = 1824; 81.0%; 95% CI: 78.9, 83.0) with chronic pain reported doing something to cope. Of the coping mechanisms assessed, over the counter (69.3%; 95% CI: 66.7, 71.9) and prescription medications (53.1%; 95% CI: 50.2, 55.9) were most commonly reported.

We restricted the following analyses to those with chronic pain and assessed the data for missingness. When reporting whether the individual was doing something to cope, missingness was 0.4%. Among those doing something to cope, missing values were present for between 0.1% to 0.9% of the observations for each barrier type, 1.2% for race/ethnicity, and 0% for sex.

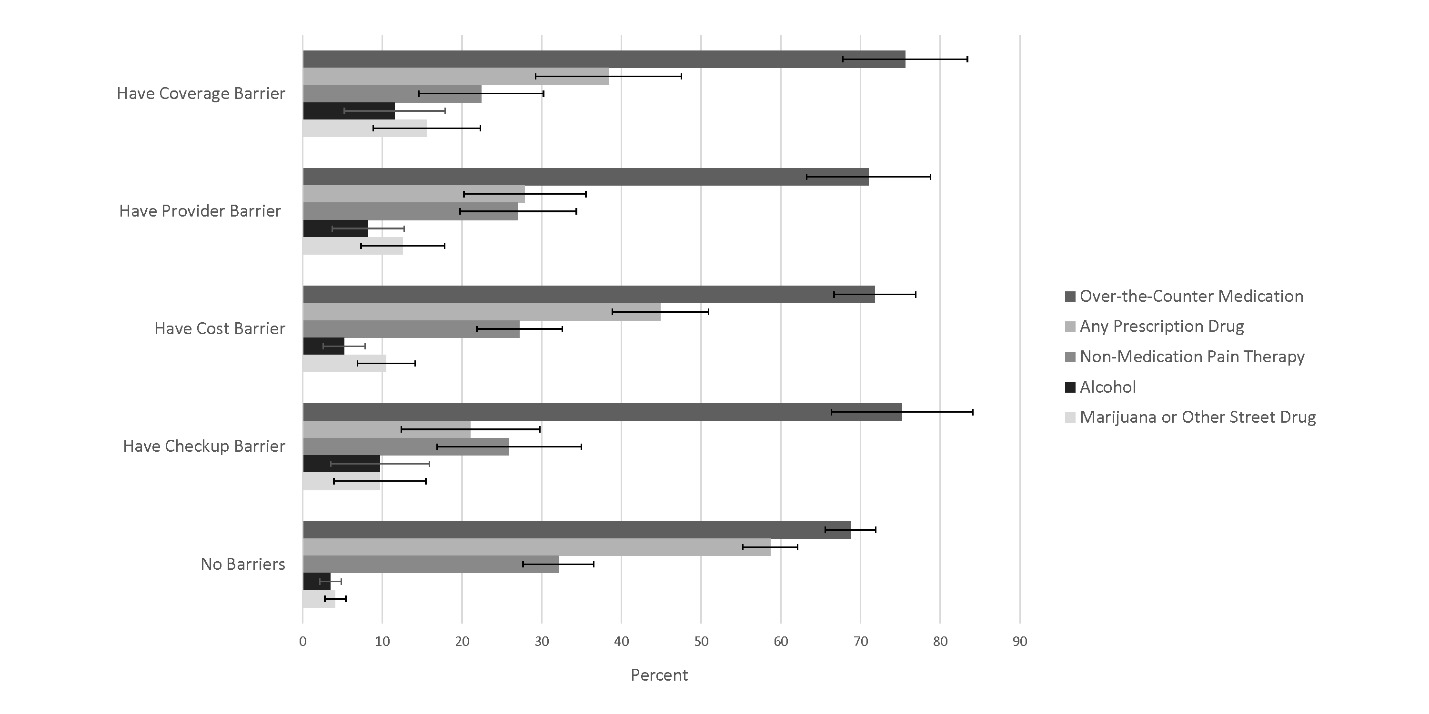

Across each health care access barrier, over-the-counter medication use was the most prevalent coping mechanism among those who reported doing something to cope (Figure 1; Appendix A). Over-the-counter medication use ranged from 71.0% (95% CI: 63.2, 78.8) for those with a provider barrier to 75.6% (95% CI: 67.8, 83.4) for those with a coverage barrier. Prescription drug use was more prevalent among those with no barriers (58.7%; 95% CI: 55.2, 62.1) as compared to those with any barrier. People with a checkup barrier reported the lowest use of prescription drugs at 21.1% (95% CI: 12.4, 29.8). The use of alcohol and marijuana or other street drugs was more prevalent among those experiencing any of the barrier types than for those with no barriers. The use of alcohol as a coping mechanism ranged from 5.2% (95% CI: 2.6, 7.8) for those with a cost barrier to 11.6% (95% CI: 5.2, 17.9) for those with a coverage barrier, compared to 3.5% (95% CI: 2.2, 4.8) for those with no barriers. For marijuana and other street drugs, a similar pattern emerged, with use ranging from 9.7% (95% CI: 3.9, 15.4) for those with a checkup barrier to 15.6% (95% CI: 8.8, 22.3) for those with a coverage barrier, compared to 4.1% (95% CI: 2.8, 5.4) for those with no barriers.

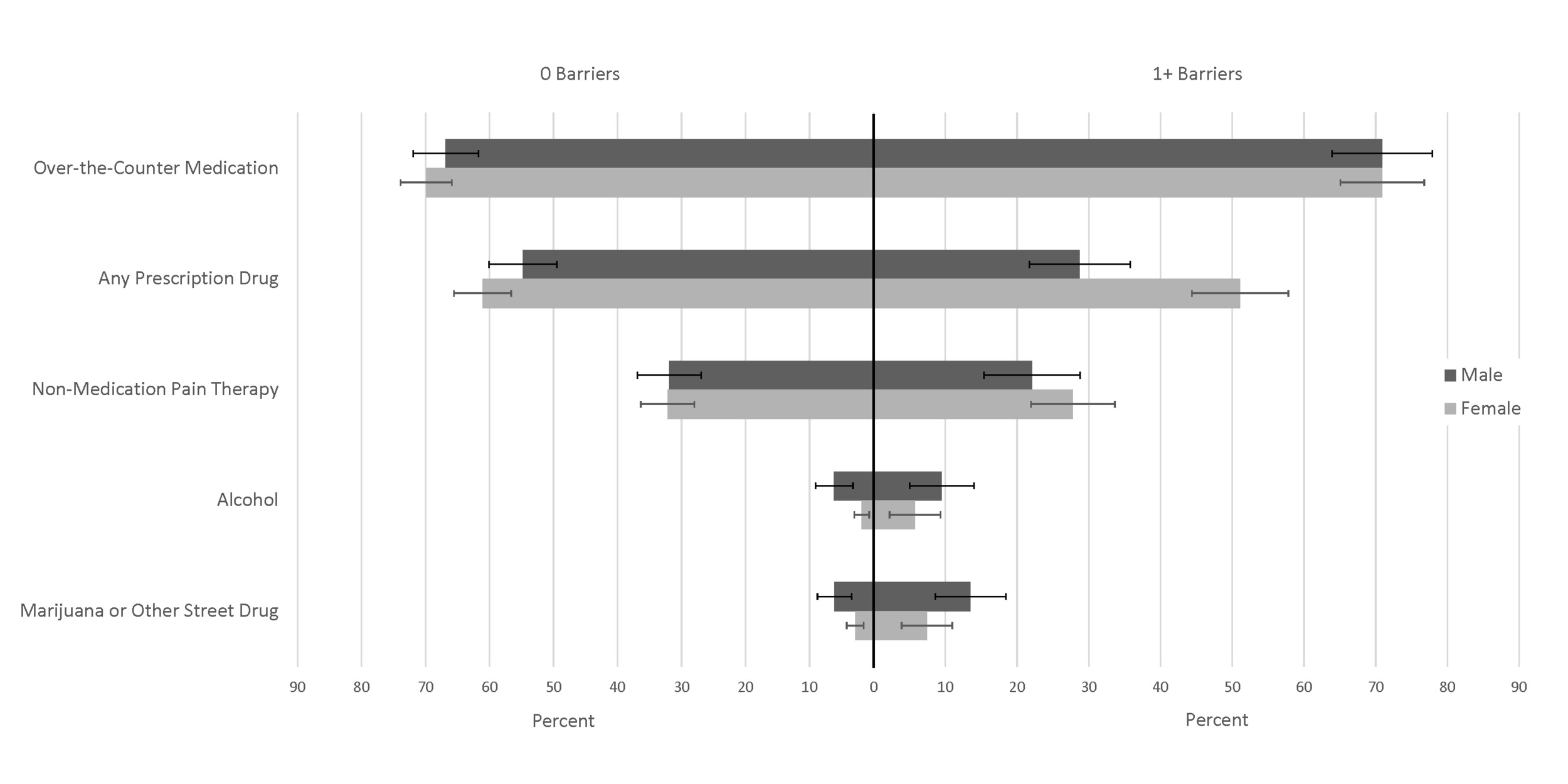

Regardless of the number of health care access barriers, men used alcohol (7.3%; 95% CI: 4.9, 9.8) and marijuana or other street drugs (8.7%; 95% CI: 6.3, 11.2) to cope more frequently than women (alcohol: 3.1%; 95% CI: 1.7, 4.5; marijuana or other street drugs: 4.3%; 95% CI: 2.9, 5.8). Women used prescription medications (57.9%; 95% CI: 54.1, 61.6) more frequently than men (45.6%; 95% CI: 41.2, 50.0). Both men and women with at least one barrier had a higher use of alcohol and marijuana or other street drugs than those with no barriers. Both men and women with no barriers had a higher use of prescription medication and non-medication pain therapies than those with barriers, though the difference was less prominent for women (Figure 2; Appendix B).

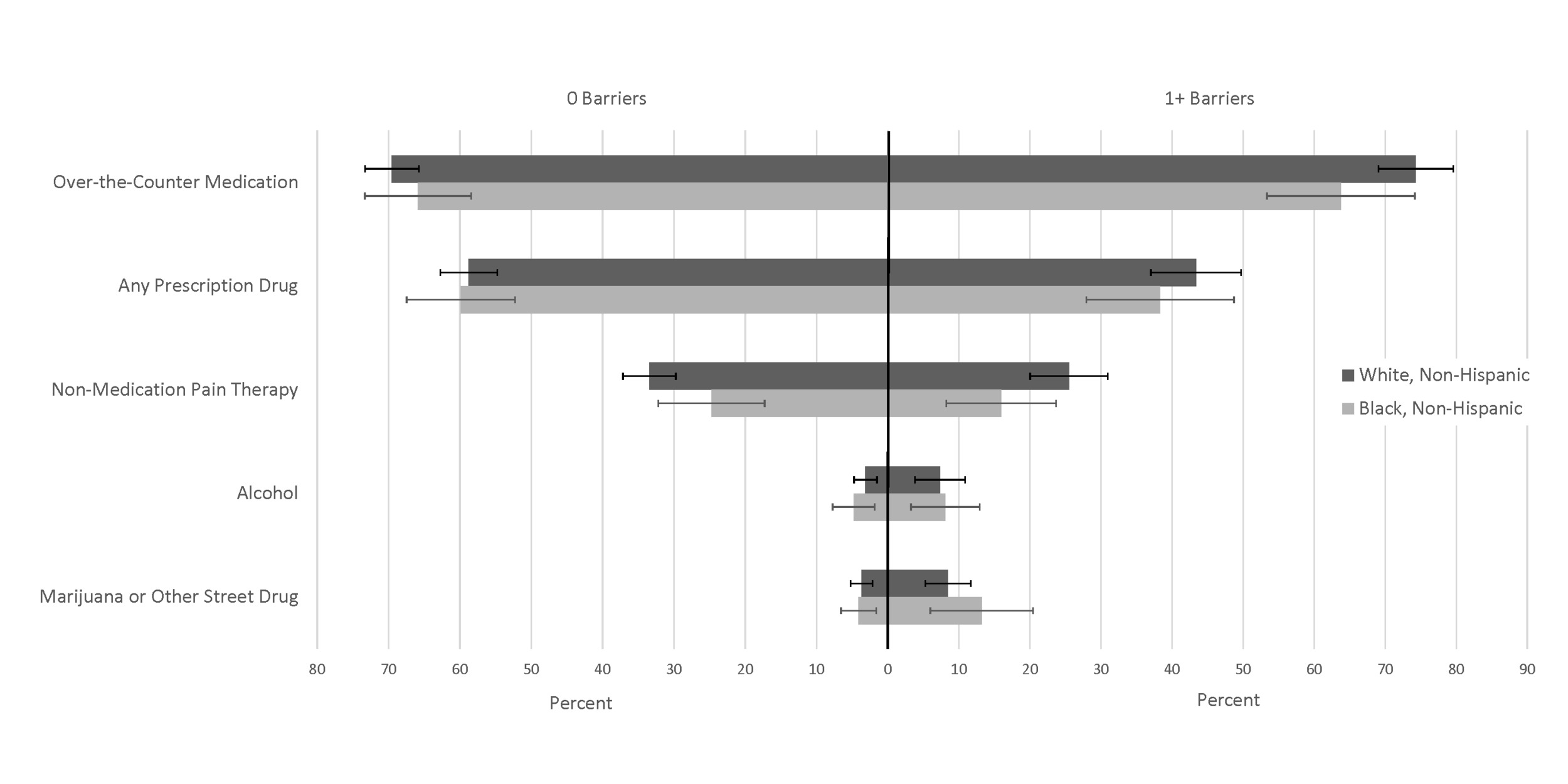

Similarly, both White, non-Hispanic and Black, non-Hispanic individuals were more likely to use alcohol and marijuana or other street drugs if they had at least one health care access barrier and prescriptions, and non-medication pain therapies if they had no barriers (Figure 3; Appendix C). Among individuals with at least one barrier, only 38.3% (95% CI: 27.9, 48.7) of Black, non-Hispanic individuals used prescription drugs and 15.9% (95% CI: 8.2, 23.7) used nonmedication therapies, compared to 43.4% (95% CI: 37.0, 49.7) and 25.5% (95% CI: 20.0, 31.0) of White, non-Hispanic individuals.

Discussion

Nearly 1 in 3 North Carolina adults experienced chronic pain in 2018–2019, which is higher than the estimated national prevalence1 and likely due to differences in the demographic composition of North Carolina, particularly its large rural and aging population.9 Of those individuals, more than 80% reported doing something to cope with pain. Over-the-counter medication use was overwhelmingly the most prevalent coping mechanism among adults with chronic pain; use was reported by about 7 in 10 individuals regardless of whether they had any type of health care access barrier. Despite advancement in evidence-based, non-pharmacological treatments for chronic pain,10 uptake continues to lag behind pharmacological treatments.11 In our data, the use of non-medication pain therapies was reported by 1 in 4 individuals with any of the health care access barriers and by 1 in 3 individuals who reported no barriers. Alcohol and marijuana/other street drugs were only used by around 5%–6% of individuals.

Coping mechanism use varied by health care barrier. Unsurprisingly, individuals with any health care barrier used coping mechanisms tied to the health care system, such as prescription drugs and non-medication pain therapies, less frequently than those with no barriers. Coping mechanisms also varied by sex. Men were more likely to use alcohol and marijuana or other street drugs than women, while women were more likely to use prescription medications. These findings support prior research, which has found that men are more likely to use non-medication substances than women,12 and women are more likely to use prescription medications than men.13

Coping mechanism differences by race/ethnicity indicated that Black, non-Hispanic individuals with at least one health care access barrier were less likely to use prescription drugs and non-medication therapies than White, non-Hispanic individuals. Research has consistently demonstrated differences in prescribing and pain therapy practices by race/ethnicity for individuals with chronic pain, indicating that Black, non-Hispanic individuals are undertreated for pain.14,15 In addition, the impacts of structural racism, including increased barriers to health care access and medical mistreatment for minoritized racial groups,16 likely exacerbates the differences observed by race and may explain the interconnectedness of coping mechanism and health care access barriers by race/ethnicity.

Collectively, results from this descriptive study provide a valuable foundation for understanding barriers to health care access and coping mechanisms used among adults with chronic pain. The most common barrier to health care access among our sample of adults with chronic pain was cost, affecting 1 in 4 individuals. Notably, North Carolina expanded Medicaid in December 2023.17 Prior studies show that Medicaid expansion is associated with reduced out-of-pocket health care costs18 and increased access to care for a variety of chronic conditions.19 Thus, expanded insurance coverage in North Carolina may help to reduce health care access barriers related to cost among those with chronic pain, though specific research in this area is needed. Prescription drugs, including prescription opioids, can be an important component of safe and effective pain management.20 In our sample, prescription drugs were less likely to be used among those with health care barriers, particularly Black, non-Hispanic individuals with health care barriers, while marijuana or other street drugs were more likely to be used among those with health care barriers. Existing research indicates that Medicaid expansion is also associated with more individuals filling prescriptions for opioids that are paid for by Medicaid,21 suggesting that the expansion of Medicaid in North Carolina may help reduce health care access barriers and facilitate access to effective, clinician-led treatments for chronic pain. However, as aforementioned, specific research in this area is needed, particularly to assess if the potential benefits of Medicaid expansion are equally realized for diverse racial and ethnic populations. Last, in our sample, the use of non-medication pain therapy to cope with chronic pain was low among both those with and without health care barriers, particularly for Black, non-Hispanic individuals. There are increasing recommendations for interdisciplinary, multimodal approaches to the treatment of chronic pain that include both over-the-counter and prescription drug use and non-medication therapies, such as physical and psychological therapy.22 However, such treatment approaches are often not equitably implemented across all populations, particularly among minoritized racial and ethnic groups and those experiencing economic disadvantage.15,23–25 Implementation and rigorous evaluation of innovative strategies, such as provider training in non-pharmacological pain treatments, bias, and stigma,11 virtual delivery of multimodal treatments,26 and nationwide insurance coverage expansion for alternative pain therapies,27 are needed to identify ways to improve access to safe and effective multimodal chronic pain management for such populations with longstanding access disparities.

This study has several limitations. The response rate for the NC BRFSS surveys was low (43.5% in 2018 and 40.8% in 2019),5 and the NC BRFSS only surveys adults with access to a landline or cell phone, both of which could bias findings. However, in analyses of BRFSS data, weighting is used to adjust for the probability of selection and for noncoverage and nonresponse.6,28 We were also constrained by the available categories for coping mechanisms (for example, the survey’s grouping of non-medication pain therapies could mask differences across modalities) and were unable to draw conclusions for those who reported using “something else” to cope with their pain. Additionally, our race/ethnicity analyses were limited to White, non-Hispanic and Black, non-Hispanic individuals due to sample size considerations and to avoid extremely heterogeneous group labels like “other” or “multi-race.” This limited our ability to understand additional differences that might exist for other racial/ethnic groups and points to the need for improved collection of race and ethnicity in national surveys to allow for further subgroup analyses. Finally, since this was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to determine temporality between health care barriers and coping mechanisms.

This study adds to the growing literature on chronic pain and provides valuable information on variation in coping mechanisms across demographic groups and interactions with structural and social determinants of health (e.g., health care access). Our findings highlight the importance of addressing inequitable health care barriers for the large population of individuals suffering from chronic pain. Tailored interventions focused on supporting equitable access to appropriate care and treatment may be key to improving quality of life for those with chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an award from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control to the North Carolina Division of Public Health (Overdose Data to Action, cooperative agreement #5NU17CE925024-02-00). The authors gratefully acknowledge the time and efforts of the North Carolina residents who responded to the BRFSS surveys. Without their participation, this work would not have been possible.

Disclosure of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial support

Authors from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were funded through a subcontract under this grant (contract #42469).