Introduction

Maternal behavioral health during the perinatal period, defined as conception through the first year following birth, affects not only maternal health and well-being but also the developing fetus, birth outcomes, and the child’s development.1 Approximately 20% of women experience behavioral health concerns during the perinatal period, and 38% report behavioral health as a top postpartum (i.e., first year following birth) complication.2,3 The societal cost of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders is approximately $14 billion.4 Suicide and overdose/poisoning related to substance use are the leading underlying causes of maternal death, accounting for nearly 32% of deaths amid this population in North Carolina and 20% to 23% of deaths nationally.5,6

Despite the high burden of mortality and morbidity of maternal behavioral health conditions, many women do not receive behavioral health treatment, especially during pregnancy. Prior research has illustrated that 75% to 80% of pregnant women experiencing depressive symptoms receive inadequate treatment or no treatment at all.7–9 Additionally, pregnant women with depression are significantly less likely to receive treatment than non-pregnant women with depression.10 Some providers are reluctant to prescribe depression medication to pregnant women due to their lack of knowledge about the safety of depression medication use during pregnancy and fears about malpractice risks.11

Although there has been a longstanding behavioral health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this concern and increased isolation and loneliness.12 Perinatal women are a vulnerable population due to the stressors of pregnancy and new parenthood, as well as high—often preventable—rates of maternal death. Given the growing concern about perinatal behavioral health, our study aimed 1) to describe the prevalence of behavioral health diagnoses and treatment received by perinatal NC Medicaid enrollees, and 2) describe the characteristics of providers treating perinatal beneficiaries.

Methods

NC Medicaid institutional, professional, pharmacy, enrollment, and provider data from January 1, 2017, through September 30, 2023, provided by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) were analyzed. Perinatal Medicaid beneficiaries were included in our study if they met the following criteria: 1) pregnant at any point during the study period,13 2) completed pregnancy (e.g., delivery, stillbirth, miscarriage, termination) or last pregnancy care visit on or before December 31, 2022, and 3) for pregnancies with unknown outcomes, must have two or more pregnancy care visits/services 30 to 183 days

apart.13 We excluded perinatal Medicaid beneficiaries who were dually enrolled in Medicare at any point during the perinatal period (i.e., pregnancy through the first 60 days following the pregnancy outcome or last prenatal care visit date). Providers were included if they were on a claim for an outcome (prescribing, behavioral health service) for at least one patient in the patient study cohort during that patient’s perinatal period.

Patient behavioral health variables were assessed during the perinatal period. The pregnancy period was calculated using the pregnancy outcome date (e.g., live birth, miscarriage) minus the calculated gestational age.13 For beneficiaries with unknown outcome, we limited their pregnancy period to the first and last dates of prenatal care.13 Behavioral health diagnoses were defined as having at least one claim with a qualifying ICD-10-CM behavioral health diagnosis. Behavioral health services, which included psychiatric evaluation, psychotherapy, and intensive behavioral health services, were identified based on CPT, revenue, and categories of service codes. The total number of services was summed per person and dichotomized as any (≥1) versus none (0) for each behavioral health service type and overall behavioral health services. Filled psychotropic prescriptions by drug class were assessed based on the prescription claim fill date. Each drug class was defined as having at least one fill with one of the generic names (any versus none). Providers were identified on the claim for that outcome. If a provider had more than one specialty, the more relevant specialty was selected.

We determined the prevalence of each behavioral health diagnosis, behavioral health service use, and psychotropic medication use by calculating the number of pregnancies that meet those criteria out of total number of pregnancies. Overall rates were calculated using each person’s first pregnancy in the study period. Yearly rates were calculated using each person’s first pregnancy in that year, allowing beneficiaries to contribute multiple pregnancies during the study period. Descriptive statistics were calculated overall and by year for patient characteristics, behavioral health diagnoses, behavioral health treatment, and overall for provider specialty type. NCDHHS and Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

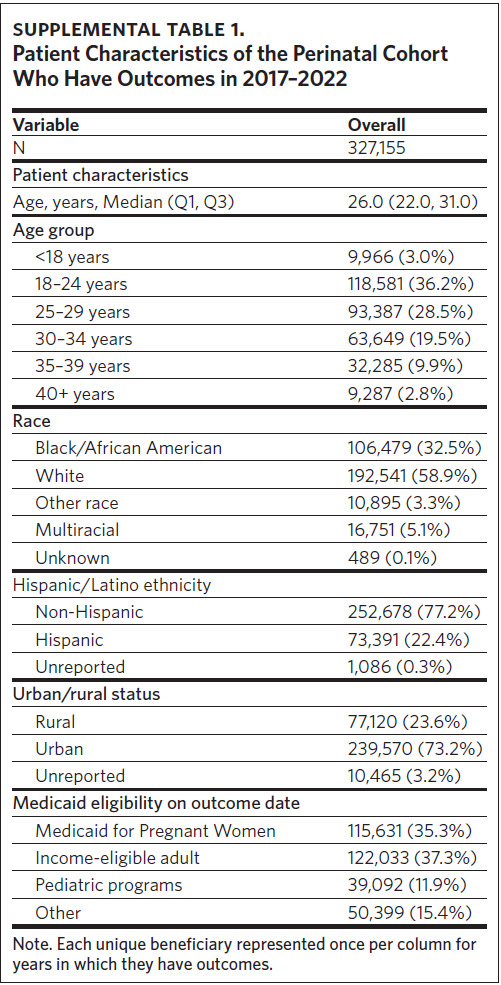

Of the 327,155 unique NC Medicaid beneficiaries who were pregnant during 2017–2022, 58.9% were White, 32.5% were Black/African American, 5.1% were multiracial, 3.3% were some other race, and for 0.1% race was unknown (Supplemental Table 1). A majority of pregnant beneficiaries were non-Hispanic (77.2%) and resided in an urban area (73.2%). The median age was 26.0 years, and most beneficiaries were eligible for Medicaid due to pregnancy (35.3%) or income (37.3%).

Behavioral Health Diagnoses

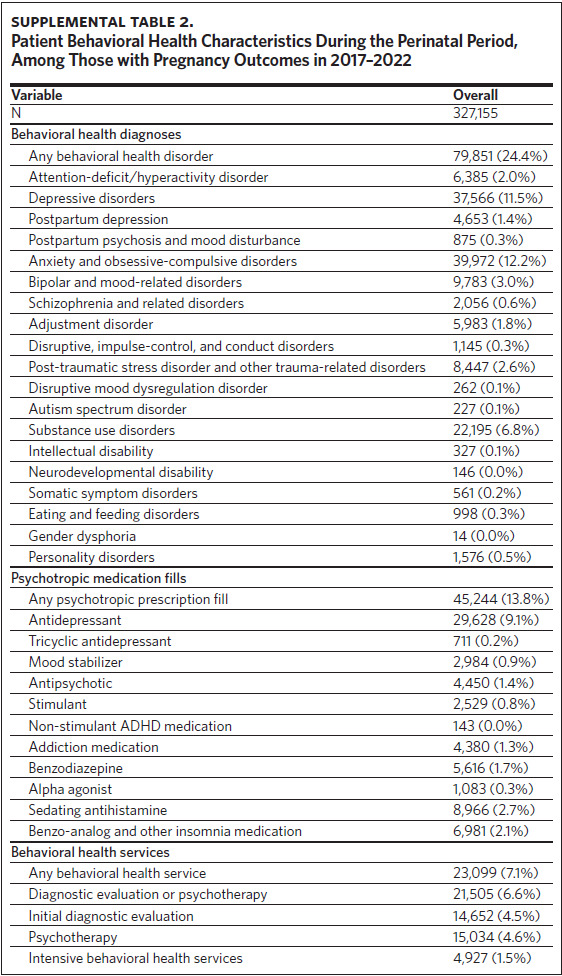

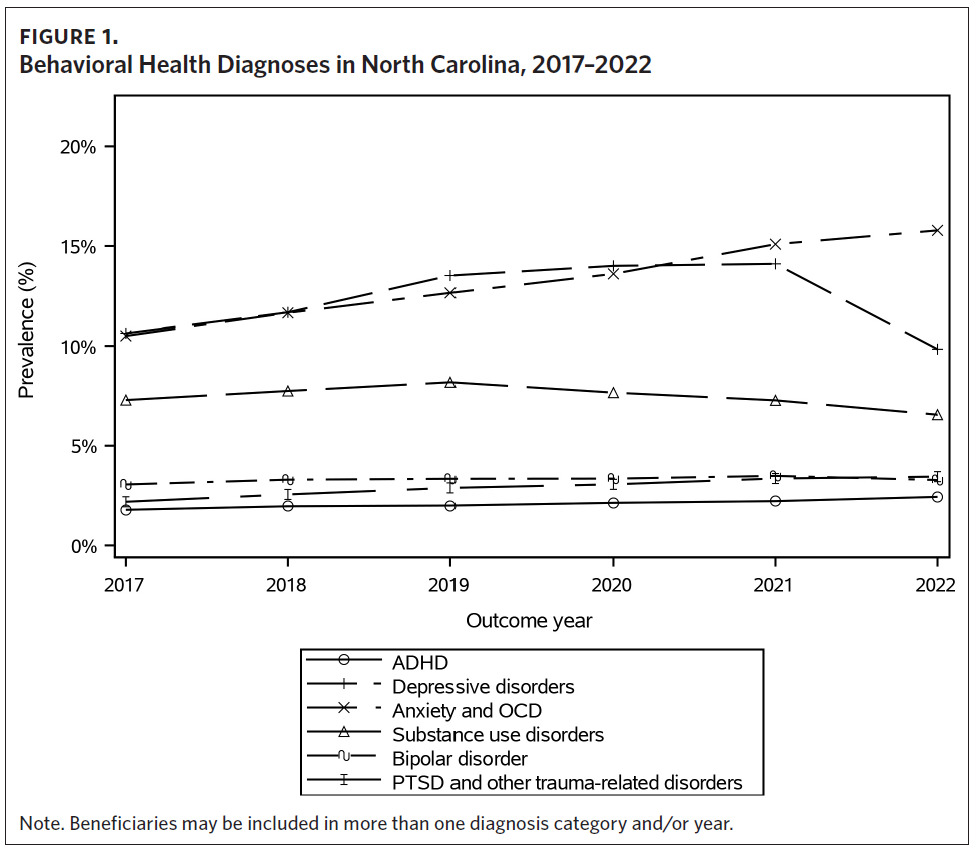

Approximately one-quarter of the beneficiaries had a behavioral health diagnosis during 2017– 2022 (Supplemental Table 2). The most common diagnoses were anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders (12.2%), depressive disorders (11.5%), substance use disorders (6.8%), bipolar and mood-related disorders (3.0%), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related disorders (2.6%), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (2.0%). The percentage of beneficiaries with any behavioral health diagnosis increased from 2017 (23.1%) to 2022 (26.8%), with the highest rate in 2021 (28.0%). The rate of anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders increased from 10.5% in 2017 to 15.8% in 2022 (Figure 1). PTSD and other trauma-related disorders increased slightly from 2017 (2.2%) to 2022 (3.4%). Similarly, the rate of ADHD increased during the six years from 1.8% in 2017 to 2.4% in 2022. The percentage of beneficiaries with depressive disorders increased from 2017 (10.6%) to 2021 (14.1%) followed by a sharp decline in 2022 (9.8%). The percentage of beneficiaries with a substance use disorder rose from 7.3% in 2017 to 8.2% in 2019 and then decreased to 6.6% in 2022. The rate of bipolar disorders remained stable from 2017 (3.1%) to 2022 (3.3%).

Behavioral Health Treatment

Between 2017 and 2022, 13.8% of perinatal beneficiaries filled at least one psychotropic prescription and 7.1% received at least one behavioral health service (Supplemental Table 2). The most common psychotropic prescriptions were antidepressants (9.1%), sedating antihistamines (2.7%), benzo-analog and other insomnia medications (2.1%), benzodiazepines (1.7%), antipsychotics (1.4%), addiction medications (1.3%), mood stabilizers (0.9%), and stimulants (0.8%). Overall, 7.1% of beneficiaries received a behavioral health service during their perinatal period; 4.6% received psychotherapy, 4.5% received an initial diagnostic evaluation, and 1.5% received intensive behavioral health services (e.g., residential substance use treatment program, halfway house).

The percentage of perinatal beneficiaries receiving any psychotropic prescription was about 16% between 2017 and 2020, before decreasing to 13.8% in 2021 and then 8.0% in 2022. The largest decline was among antidepressant prescriptions (Figure 2), with a decrease from 10.5% in 2017 to 3.0% in 2022. Prescriptions for benzodiazepines and addiction medications also declined from 2017 (2.5% and 1.5%, respectively) to 2022 (1.5% and 0.8%, respectively). The percentage of stimulant prescriptions remained stable during the study period. Among those who received any behavioral service, the percentage slightly increased from 2017 (7.3%) to 2022 (7.9%). A larger percentage of beneficiaries received psychotherapy in 2022 (5.2%) compared to in 2017 (4.7%) (Figure 2). A decrease in intensive behavioral health services was seen during the study period with 1.7% receiving this service in 2017 compared to 1.3% in 2022. The rate of initial diagnostic evaluations remained stable from 2017 to 2022.

Provider Specialty

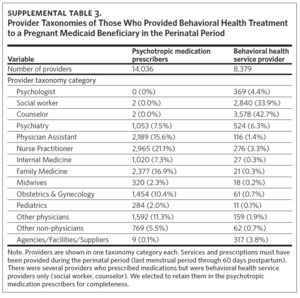

During 2017–2022, 14,036 unique providers prescribed a psychotropic medication to these beneficiaries (Supplemental Table 3). Among the prescribers, one-third were nurse practitioners (21.1%) and physician assistants (15.6%) (Figure 3). Other prescribing providers included family medicine (16.9%), obstetrics and gynecology (10.4%), internal medicine (7.3%), midwives (2.3%), pediatricians (2.0%), and other physicians (11.3%). Psychiatry providers (i.e., psychiatrists) only accounted for 7.5% of all unique prescribers. For behavioral health services, perinatal Medicaid beneficiaries received treatment from 8,379 unique providers (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined trends of behavioral health diagnosis and treatment among perinatal Medicaid beneficiaries in North Carolina from 2017 through 2022. Results indicated that about 1 in 4 beneficiaries had a behavioral health diagnosis, similar to findings by Fawcett and colleagues.2 The rate of behavioral health diagnoses may be under-identified given that 13% to 20% of women are not screened for depression during pregnancy or postpartum.7 The overall rate of diagnosis increased from 2017 to 2022, which reflects a worsening of behavioral health symptoms that may be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, consistent with prior findings.14

While there was an increase in the overall rate of diagnoses from 2017 to 2022, there was a decrease in the percentage of beneficiaries with a depressive disorder, which dropped to below the pre-pandemic rate in 2022. The decrease in depressive disorders in 2022 is in contrast to the slight increase in anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders from 2021 to 2022. Although we did not have access to screening rates for this analysis, it is possible fewer women were screened for behavioral health concerns—specifically depression—during this year compared to prior years. One study found that those with a telehealth visit who were enrolled in Medicaid were less likely to have a depression screening completed during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to those with an in-person visit and private insurance.15 Many national organizations have recommended behavioral health screening during the first and second half of pregnancy and during the postpartum period, but there is a lack of consensus regarding frequency, timing, and process related to screening.16–20

A greater proportion of beneficiaries received psychotropic prescriptions than behavioral health services, which is likely due to the limited availability of psychotherapy providers and other social drivers of health. National organizations recommend the use of medications to treat perinatal depression and anxiety, but many times patients and providers have concerns about the potential risks to the fetus.21,22 Providers treating perinatal patients often do not receive sufficient training on management of behavioral health conditions.23 We found that approximately 37% of unique providers prescribing psychiatric medications to perinatal beneficiaries were nurse practitioners and physician assistants, suggesting limited behavioral health training. Our study found that antidepressants were the most common psychotropic medication prescribed to perinatal patients overall, but there was a stark decline in these prescriptions from 2020 to 2022, which is likely related to the decrease in the rate of depressive disorders in 2022. Other factors that may have influenced the rate of antidepressants include patient preference, limited access to prescribing providers, and lack of provider comfort and knowledge.

Perinatal psychiatry access programs can help address the behavioral health needs of perinatal women. NC MATTERS (Making Access to Treatment, Evaluation, Resources, and Screening Better) is a state and federally funded program that offers provider-to-provider consultation and education regarding assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of perinatal behavioral health conditions in North Carolina. This program aims to increase the capacity of health care providers to manage behavioral health conditions among perinatal patients.24 As the NC MATTERS program continues to expand over time, the number of providers treating perinatal beneficiaries will likely increase and result in more perinatal women getting the behavioral health care that they need, including diagnosis and prescriptions.

Our study had several limitations. First, our sample was limited to beneficiaries with continuous Medicaid coverage during the perinatal period and thus our findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Additionally, since we only examined behavioral health diagnoses and treatment at conception through the first 60 days following birth, we did not know if beneficiaries received behavioral

health treatment later in the postpartum period. Given the nature of claims data, we were unable to assess the validity of diagnoses, the rate of screening, and the timing of the diagnosis in relation to the receipt of treatment.

While behavioral health conditions are common among perinatal women, there are barriers to accessing care for these conditions. Future research should aim to better understand how to increase early detection and improve diagnosis and treatment of perinatal behavioral health conditions as well as how policies and initiatives may impact access to care and behavioral health outcomes, such as Medicaid coverage extension through 12 months postpartum, expansion of and increased capacity of the perinatal behavioral health workforce, and increased access to care. Furthermore, it will be important to also examine the role of health disparities in perinatal behavioral health care and identify strategies for addressing structural inequities.

Disclosure of interests

Dr. Gary Maslow receives grant support from Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), NC Medicaid, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, and Healthy Blue and has received research funding from Pfizer, the National Institutes of Health, and the Arc of North Carolina.

Dr. Mary Kimmel was a PI on an investigator-led study with Sage Therapeutics, which ended over a year ago. Her spouse has some stock in Abbvie.