The health and well-being of religious leaders, especially Protestant clergy, has been an area of both interest and concern among researchers. On one hand, religious organizations and church-based health promotion interventions have great potential to play a positive role in influencing the health behaviors of their congregants.1,2 It is important to consider the health of faith leaders, as they are often in positions to serve as role models of well-being and are able to draw on scriptural influence, social influence, and trusting relationships with congregants to promote health behaviors in their communities.3,4 Although clergy have historically demonstrated a significant mortality advantage compared to other professions and religion has been hypothesized to confer a protective effect toward both mental and physical health,5–7 research suggests that there may actually be heightened health risks for the leaders within these religious communities. According to recent data, Protestant clergy exhibit higher rates of various chronic conditions, including obesity,8–10 hypertension,11,12 and diabetes.13,14 Significant variations within subgroups of clergy are also notable, including mainline Protestant clergy showing significantly higher body mass index (BMI) compared to Catholic and non-Christian clergy.15 Additionally, Black clergy report higher BMI, diabetes, and hypertension, and lower physical health functioning compared to White clergy,16 following national trends in racial health disparities.17

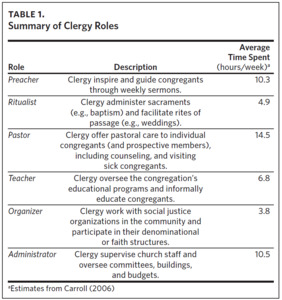

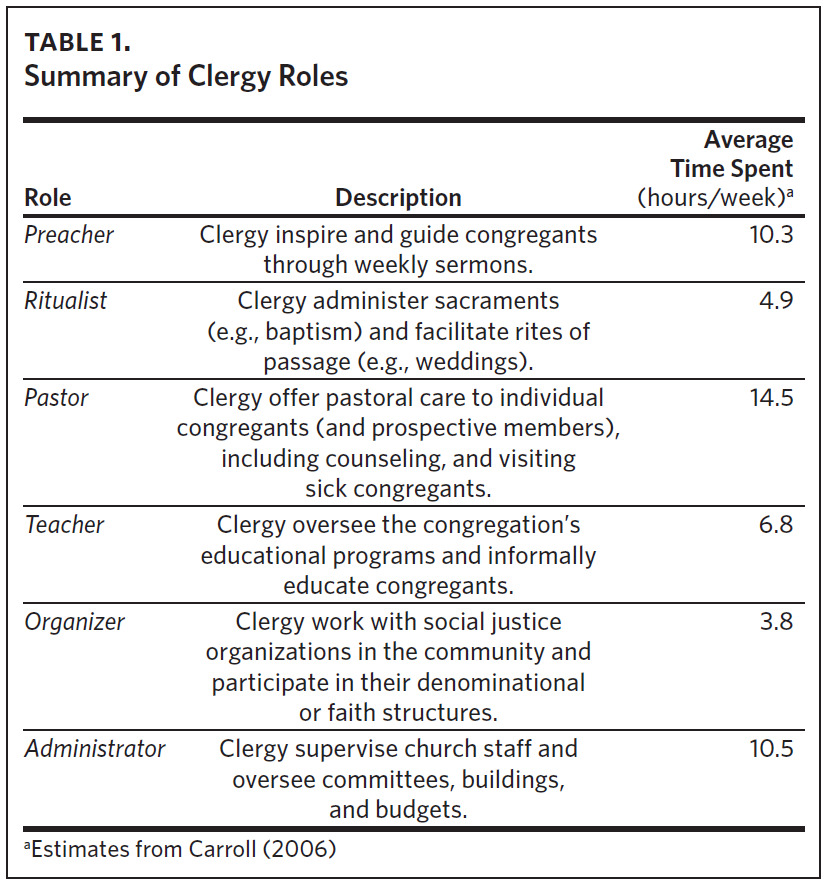

While clergy from different denominations and faiths experience different stressors, burnout across clergy has been found to be on par with that of teachers and social workers,18 indicating the presence of stressors that may heighten health risks. Clergy take on a wide range of broadly defined roles within ministry19 that can be organized into 6 categories, including preacher, ritualist, pastor, teacher, organizer, and administrator (Table 1 contains a summary of roles).20,21 While many pastors establish a basic structure for their weeks based on these categories of work (e.g., sermon preparation on Tuesday, committee meetings on Wednesday), most of those days involve switching between many and varied roles and having to shift plans without warning due to the urgent needs that arise. Their days are often characterized by “interruptions” that are, in fact, a significant part of ministry. For example, on a typical day, a pastor might arrive at the hospital at 6:30AM to pray with a parishioner before surgery—a parishioner who may not have attended church in several months and has been critical of the pastor’s preaching as being too political. The pastor then drives to the office to read and study scripture in preparation for Sunday’s sermon, only to be interrupted by another parishioner who drops by for the third time in as many weeks to talk about the evil forces that are out to destroy him. The pastor suspects an undiagnosed mental health issue but has been unable to convince the person to seek counseling. This might be followed by a meeting with the Finance Chairperson to go over the budget, a conversation with a staff member about the lack of nursery volunteers, and a call about the church’s broken sound system. Because of a need to return to the hospital to check on the surgical patient, the pastor may get fast food. Clergy, on average, have 4 evening meals away from home each week.21 The pastor arrives home late in the evening, not having done any of the sermon prep he intended at the beginning of the day and missing reading a bedtime story to his young children.

Increasingly, clergy serve as “first responders” to a growing mental health crisis in the United States.22,23 Furthermore, the experience of clergy has been characterized as having blurred boundaries of work, with pastors being on call outside of a structured work schedule.18 The adverse effects of such work-related and boundary-related stressors are significantly associated with pastors’ physical and emotional health.24 A recent meta-analysis suggests that clergy from numerous denominations and faiths in the United States have obesity rates similar to those of the general population, indicating that they are able to navigate these stressors without a physical health toll above that of the average American.15 However, data from this nationally representative study report that between clergy groups, mainline Protestant clergy have higher obesity rates compared to Catholic and non-Christian clergy, and clergy in the Southeastern United States have higher obesity rates compared to those in the Northeastern United States, raising special concerns for United Methodist Church (UMC) clergy, who work in one of the largest mainline denominations in the South.15,25 Scholars suggest that food has historically played an integral part in religious community life, with some religious leaders identifying food traditions, such as potlucks, as potential barriers to healthy eating.26,27 Research shows that the limited availability of healthier foods in rural environments, coupled with tradition, may play a role in shaping what is offered at church events.28 Rural communities may also present fewer recreational facilities, further contributing to an obesogenic environment.29

In North Carolina, prior analyses of religious leaders within the UMC revealed that clergy exhibit significantly higher rates of obesity, diabetes, arthritis, high blood pressure, angina, and asthma compared to their fellow North Carolinians.8 This seminal work raised concerns about the health risks of UMC clergy, and possibly clergy overall. In 2023, the Wespath Clergy Well-Being Survey showed that average rates of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension increased among UMC clergy nationally compared to previous years,30 although the survey is limited by a 25% response rate and the lack of adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics.

Several changes in the broader health patterns of the general US population and among North Carolinians warrant an updated review of physical well-being among UMC clergy. Research indicates that obesity has increased significantly in the last few decades. From 1999 to 2000, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 30.5%. By 2017–2018, there was a 39% increase, with a 95.7% increase in severe obesity (i.e., class 3 obesity), during the same period.31 Based on 2021 data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) reported 19 states having adult obesity rates over 35%,32 with North Carolina having a 36% prevalence of self-reported adult obesity.33

In addition, many North Carolinians are likely to suffer from the complications associated with obesity. According to the 2017 North Carolina BRFSS surveys, 87% of people with diabetes, 81% with high blood pressure, 77% with a history of heart disease or stroke, and 78% with high cholesterol were overweight or obese.34 In the present study, we revisit the North Carolina clergy data—now longitudinal—to investigate more closely how the rates of chronic disease among UMC clergy may have shifted in recent decades and how the rates of physical health among clergy compare to their fellow North Carolinians. Should we remain concerned about the physical health of UMC pastors in North Carolina compared to the general population, or have the differences in physical health diagnoses between these populations been mitigated in recent decades?

Methods

Drawing on data from the BRFSS and the Clergy Health Initiative (CHI) longitudinal study, we use data from the years 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2019, and 2021a to examine the physical health of UMC pastors compared to the general North Carolinian population.

For the CHI study, a longitudinal survey of UMC pastors in North Carolina (NC-UMC), all UMC clergy in the state of North Carolina with current appointments, including recently retired clergy, were invited to participate in an hour-long questionnaire. The total number of participants per wave ranges from 1451 to 1802 clergy members across the 7 waves, with response rates ranging 72%–95%. The majority of the data were collected in August to November of each survey year (details on CHI survey in Appendix A). All procedures were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (IRB), and survey waves through 2016 were additionally approved by the Westat IRB.

For our data on the general population, we drew from the BRFSS, which includes measures about US residents by state regarding their health-related behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services. Data were collected by in-house interviewers or by telephone using random digit dialing techniques for both landline and cell phones. The total number of participants ranged from 2369 to 8402 in North Carolina, with response rates ranging 38%–43%. All BRFSS data were publicly available and retrieved from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/).

Measures

To compare the physical health of UMC clergy to the general North Carolinian population, we used self-reported measures of hypertension, high cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia), diabetes, angina, arthritis, and asthma. The CHI survey items for these health measures used the same wording as the BRFSS—i.e., “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that your blood cholesterol is high?” (further details on question wording and response categories are included in Appendix B). The response categories that we use in our analyses for each self-reported health measure are dichotomous (yes/no).

To calculate body mass index (BMI) scores, we used self-reported measures of height and weight. With the BMI scores, we determined whether individuals are obese (BMI ≥ 30) and whether individuals have class 3 obesity (BMI ≥ 40) for all respondents, except for those identifying as Asian or Asian American, for whom we used cutoffs of BMI ≥ 27.5 for obesity and BMI ≥ 35 for class 3 obesity. BMI categories were created using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute definition for the general population and the World Health Organization definition for Asian respondents.35,36

Analytical Approach

Our analyses consist of 2 main components. First, we examined the prevalence of each physical health condition among NC-UMC clergy and the general North Carolina population from 2008 to 2021. To do this, we calculated the prevalence of each health condition for the 2 samples (applying sampling weights to the BRFSS data) and summarized these unadjusted rates graphically. Though not available for the BRFSS data, we additionally modelled the changes in each health condition’s prevalence over time using CHI’s longitudinal data, which we include in Appendix C.

In the second component of our study, we focused on the physical health of NC-UMC clergy and the general North Carolina population in 2021, and we compared the prevalence of each health condition using predicted probabilities from logistic regressions, adjusting for age, sex (female, male), and race (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, other). As the UMC clergy are more likely to be older, male, and White compared to the general North Carolina population, the adjustments in the regressions take these sociodemographic characteristics into account. We limited our analytical sample from the BRFSS to individuals in North Carolina who are currently working or have worked within the last year, and we limited the CHI sample to clergy who have ever been actively appointed and serving in ministry in at least 1 of the survey years (i.e., excluding: fully retired, disabled and not serving, inactive, on leave, new and yet to be appointed, and had left UMC ministry).b

Results

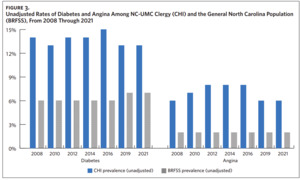

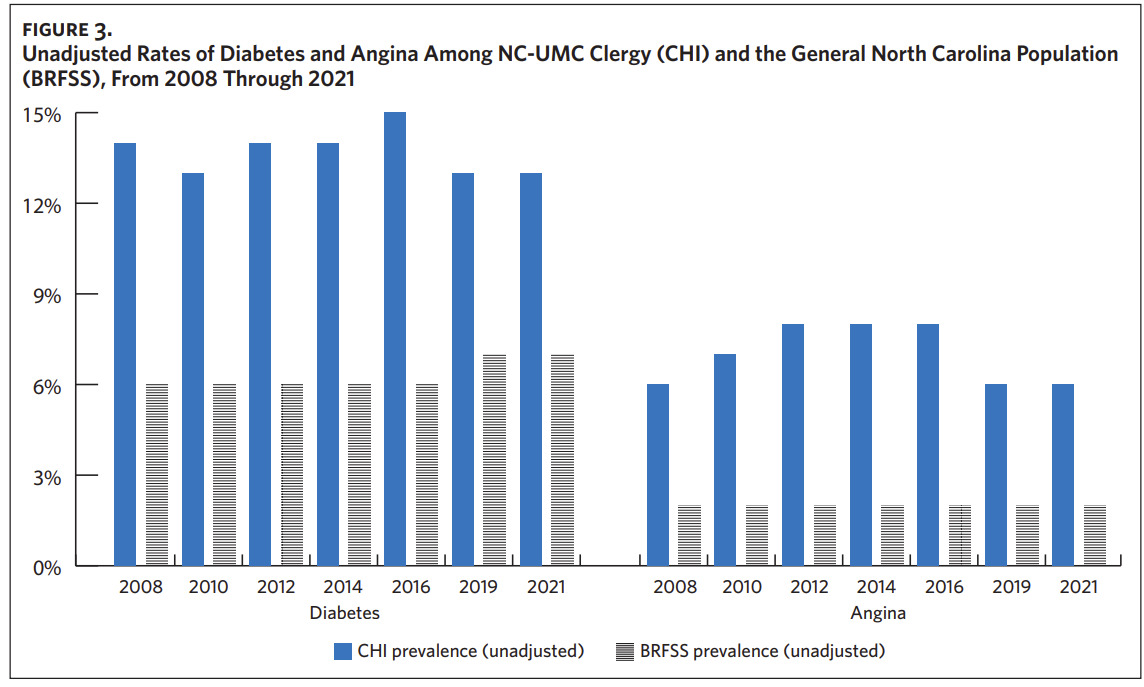

Using the unadjusted prevalence of physical health conditions among NC-UMC clergy and the general North Carolina population from 2008 through 2021, we constructed comparative graphs that illustrate the overall patterns of health within these two populations in recent decades (Figures 1–4). Notably, in observing the unadjusted rates of obesity (classes 1–3) and severe obesity (class 3) among UMC clergy and the general population, we find that obesity has increased in both samples at similar rates across the years and that the prevalence of obesity remains higher among UMC clergy relative to the general population for all waves of data from 2008 through 2021. There is a similar pattern of increase across the years in asthma between the two samples as well, with the prevalence of asthma being higher among UMC clergy relative to the general population.

For all other physical health conditions that we observed (i.e., hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, angina, and arthritis), there is not a clear pattern of increase across years, but we find that the unadjusted prevalence of these health conditions remains consistently higher among NC-UMC clergy compared to the general North Carolina population from the years 2008 through 2021. For example, the prevalence of diabetes and that of angina among UMC clergy remain consistently about twice as high as that of the general North Carolina population across all waves.

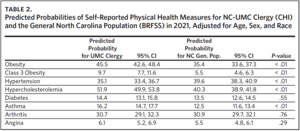

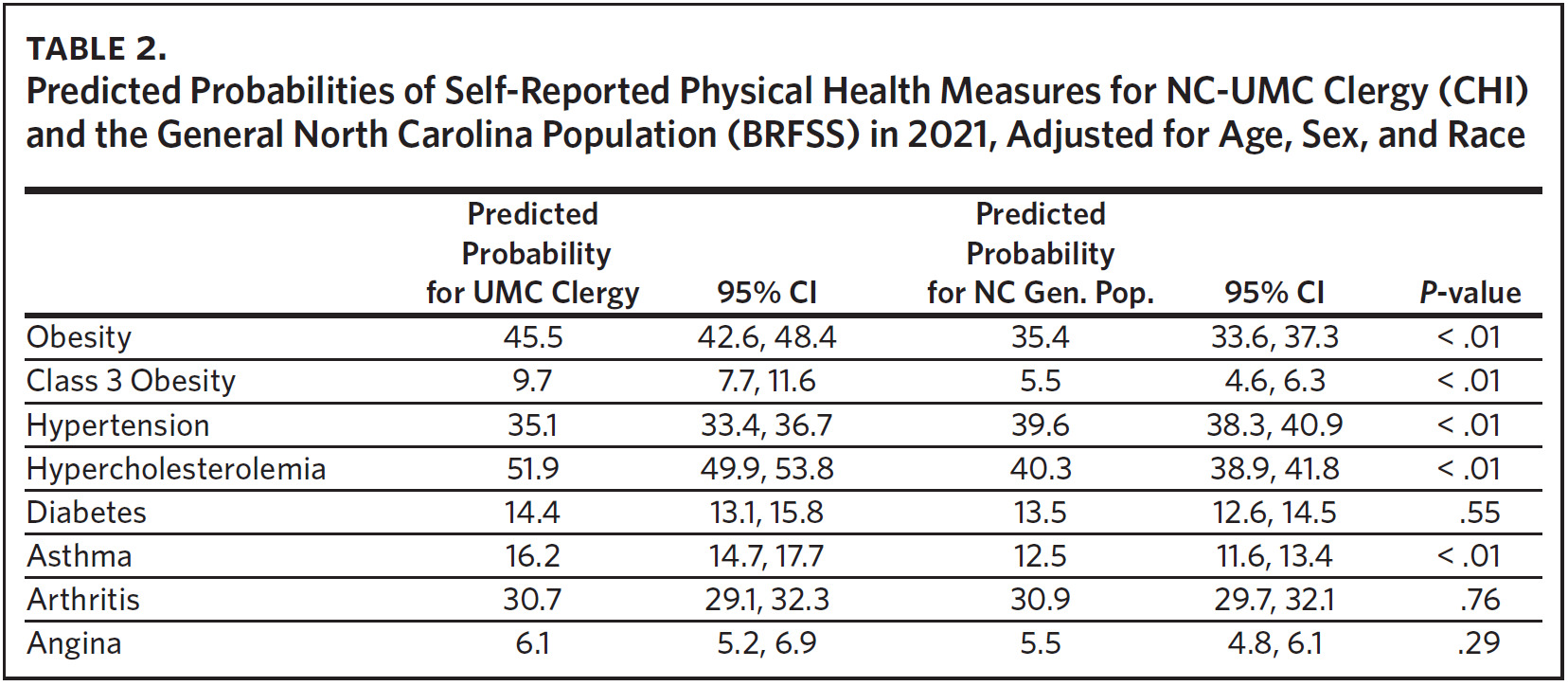

Adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics using predicted probabilities calculated from logistic regressions, we find some notable differences in the overall patterns of physical health between UMC clergy and the general North Carolina population (Table 2). Our analyses indicate that NC-UMC clergy have significantly higher rates of obesity (classes 1–3 combined), severe obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and asthma when compared to their North Carolina counterparts. In particular, the predicted probability of class 3 obesity among UMC clergy is 9.7%, compared to 5.5% in the general North Carolina population. We did not find significantly higher rates of diabetes, arthritis, and angina for UMC clergy after adjusting for age, sex, and race (at a 5% statistical significance level). Contrary to prior studies, we found that UMC clergy have significantly lower rates of hypertension compared to their North Carolinian counterparts (with predicted probabilities of 35.1% and 39.6%, respectively) after adjusting for age, sex, and race.

Discussion

This study provides an updated status of the physical health of NC-UMC clergy, using data across multiple waves since 2008 to make direct comparisons to the general North Carolina population. Our analyses indicated that the overall pattern of unadjusted differences in physical health between UMC clergy and North Carolinians overall remained relatively consistent from the years 2008 through 2021, even with considerable increases in obesity in the general US population in recent decades.

However, taking into account age, sex, and gender, the UMC clergy in our study displayed significant differences only in higher rates of obesity, class 3 obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and asthma when compared to their fellow North Carolinians in 2021. Because obesity is a proven risk factor for hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers,37 UMC clergy may still be likely to have an increased metabolic risk compared to the general population. Although there was no significant difference in diabetes between the 2 samples in our study in 2021, we note that the higher rates of obesity and severe obesity are likely to place UMC clergy at an increased risk for insulin resistance and diabetes development. Interestingly, our analyses indicate an unexpected pattern where NC-UMC clergy in 2021 have lower predicted probabilities for hypertension compared to their other North Carolinians, in contrast to obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and asthma. Further, we note that the prevalence of hypertension in North Carolina is comparable to that of the general US population as well (approximately 39%).

We cannot be certain of an explanation for this surprising finding of hypertension. We consider the possibility that this difference may be explained in part by the exposure of approximately 52% of the clergy group to either the Spirited Life holistic health or Selah stress management behavioral trials, which provided interventions from 2010–2014 and from 2019–2021, respectively.11,38 Spirited Life was an intervention that targeted symptoms of metabolic syndrome, depression, and stress in United Methodist clergy. Although the trial showed remarkable physical health outcomes including improvements in blood pressure and increase in HDL cholesterol, it suggested a need for further focus on stress reduction, which led to the Selah intervention studies on 389 people of this same population of United Methodist clergy in North Carolina in 2019–2021.39 The Selah pilot and stress management trial studies examined changes in stress symptoms and heart rate variability following 1 of 4 interventions (stress inoculation training, mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR], the Daily Examen prayer practice,40 and Centering Prayer [tested only in the pilot study]).41 In the trial, compared to a control group, participating clergy in all 3 interventions reported fewer stress symptoms at 6 months, although only participants who received MBSR (n = 107) saw significant improvements in heart rate variability,42 which is associated with improved blood pressure.43 Thus, stress management interventions may have contributed to lower hypertension rates.

One limitation of the current study is that our findings on clergy health are specific to one denomination of Christian clergy in the state of North Carolina. Although we consider various risk factors that are present in the experience of clergy generally and which may be linked to a higher risk of health conditions, our current analyses cannot speak definitively to whether these disparities are more likely to result

from occupational stressors inherent to the clergy profession or other contextual factors, including those specific to North Carolina. Indeed, the recent study by Holleman and Eagle15 suggests that other contextual factors should be considered. As our findings do confirm the persisting pattern of health disparities experienced by UMC clergy, more research is needed to investigate the particular mechanisms that may contribute to the higher prevalence of obesity and chronic disease among the UMC, such as assigned relocation, which occurs in the UMC and only a few other clergy groups.

The literature offers several areas for additional study related to the physical health of clergy, including role expectations, lack of work-life boundaries, and burnout as risk factors, and social support as a potential protective factor.44 Obesity is found to be positively and significantly correlated with longer work hours, bi-vocational status, work-related stress, and boundary-related stress among clergy.9,24 Overall, stress may alter metabolism, while emotional eating may serve as a form of coping for individuals who are overworked and burned out.9,10 However, social support can moderate the negative effects of stress on physical health and has been found to be significantly related to physical and mental health functioning.11,45,46 A study of seminary students also points to the possibility of substantial exposure to adverse childhood experiences.47 The odds of obesity in adulthood significantly increase following exposure to multiple adverse experiences in childhood, especially as a result of social disruption, changes in health behaviors, or chronic stress response.48

We recognize that there may be limitations in the self-reporting of physical health conditions within the CHI and BRFSS data, which ask respondents whether they have ever been diagnosed with a given health condition, so we are cautious to suggest broader interpretations about the exact timing of these physical health conditions. We acknowledge that it is possible for clergy members to be more or less knowledgeable about their physical health compared to the general North Carolinian population; as a result, they may be more or less likely to share this information on a survey, which would pose potential reporting bias.

Of note, the 2019 and 2021 data were collected while UMC clergy were undergoing substantial changes in navigating policies related to same-sex marriage and the sexuality of ordained clergy. In addition to the increasing role of politics in churches during these years, the 2021 data were collected from the months of August through December, when the COVID-19 Delta variant was becoming more widespread and concerns about COVID-19 remained. However, to varying degrees, Americans were becoming more comfortable with resuming many everyday activities, including worship services.49 While these stressors are relevant to the 2019 and 2021 waves, a pattern of above-average non-communicable disease (NCD) prevalence rates had already been established prior to these recent contextual changes.

Conclusion

Overall, this study suggests that substantial health risks remain for UMC clergy, who exhibit significantly higher rates of obesity, class 3 obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and asthma, with these differences persisting over 14 years. Our findings provide an updated status of the specific health conditions that especially impact NC-UMC clergy and highlight a continuing need to pay attention to the health and well-being of this group of leaders within North Carolina’s religious communities. Targeted interventions and further research should be considered to address the mechanisms that underlie these persisting health disparities.

b Although not included here, we conducted sensitivity analyses to consider possible effects of health insurance status, binge drinking, and smoking on differences in health between the UMC clergy and general population. We found that results do not change substantially even with these adjustments.

Disclosure of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Financial support

This study was funded by a grant from the Rural Church Area of The Duke Endowment. The Duke Endowment is also a major funder of this journal.