The 3 core missions of academic health centers (AHCs) have traditionally been patient care, research, and education.1,2 The current changing health care environment requires AHCs to continue to offer specialized tertiary care services to patients while also broadening their focus to improve the health of populations.3 The Affordable Care Act (ACA)4 brought new interest to the community benefits that tax-exempt hospitals provide to the communities they serve, as well as their ability to directly address social determinants of health (SDOH). To adapt to this new paradigm, AHCs need to identify innovative ways to make population health part of their core mission3 by addressing SDOH.2,5

Many not-for-profit health care systems have community benefit programs, defined as “programs or activities that provide treatment or promote health and healing in response to identified community health needs and meet at least one of these community benefit objectives: improve access to health services, enhance public health, advance increased general knowledge, or relieve the burden of government to improve health”.6 In 2008, the Internal Revenue Service added section H to the Form 990, including categories that may qualify as community benefits. The ACA added 3 types of community benefit requirements in section 9007: 1) community health needs assessments (CHNA) that identify key health needs and issues at least once every 3 years; hospitals are required to report on community benefits; 2) written policies for financial assistance and emergency care policies; and 3) limits on charges, billing, and collection activities for uninsured individuals.4 These provisions encouraged tax-exempt hospitals to invest in community health benefits. However, average spending for all community benefits only increased from 7.6% in 2010 to 8.1% in 2014, most of which went to unreimbursed patient care rather than community health improvement.7

Health care reform is shifting the landscape from focusing on volume and quantity to value and quality, but AHCs are not yet aligned with this shift. This study seeks to: 1) evaluate the contributions of the 5 North Carolina AHCs’ activities in terms of benefiting their community, and 2) explore how AHCs are partnering with local and national organizations and identify challenges they face when addressing SDOH to improve the health of their patients and communities.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in the 5 North Carolina AHC flagship medical centers: UNC Hospitals (part of UNC Health); Duke University Hospital (DUH), part of the Duke University Health System (DUHS); Vidant Medical Center (VMC), part of Vidant Health (now ECU Health); Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (WFBMC), part of Wake Forest Baptist Health (now Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist); and Carolinas Medical Center (CMC) (now Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center). Each of these AHCs has several smaller hospitals within the larger systems.

Data Sources

We used an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design study. For the quantitative part of the study, we analyzed financial data from community benefits reports and Form 990 Schedule H (when available). North Carolina hospitals voluntarily submit community benefits reports to the North Carolina Healthcare Association (NCHA) that include estimated costs of treating patients eligible for charity care, community health improvement services and community benefit operations, health professions education, and community-building activities. Form 990 Schedule H has 6 parts, including charity care, other community benefits costs, and community building activities that directly address all SDOH described in Healthy People 2020. Financial data for expenses reported in the community benefits for 2018 were collected from the NCHA website.8 UNC Hospitals and CMC were not required to file a Form 990 because they are instrumentalities of states or political subdivisions. Form 990 was available for the other 3 AHCs. Form 990 Schedule H information was accessed via the GuideStar website, where available.9

We complemented these quantitative analyses with 4 key informant (KI) interviews at each of the 5 AHCs to learn about each organization’s efforts to address SDOH, including those defined by Healthy People 202010: economic stability, education, social and community context, health and health care, and neighborhood and built environment. The interview guide focused on opportunities through which their organization contributed to each area and the main challenges they experienced or anticipated. Prompts were used to encourage deeper thinking. The final interview guide was revised based on pilot testing with an administrator outside the North Carolina AHCs.

KIs were administrators at the manager level or above, or faculty working in population health; they were identified by their described role on AHC websites or personal connections. Snowball sampling was used to identify other KIs until 4 were interviewed at each site. We emailed KIs to describe the purpose of the study, expectations for the interview, and strategies for ensuring confidentiality of responses. The email asked recipients who could not answer questions to provide alternative contacts. We sent 2 follow-up emails 1 week apart if we received no response. When participants agreed, we scheduled a video interview. All participants gave oral consent (including permission to record the session). We recorded sessions using a digital audio recorder and then transcribed each interview. This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Analysis

Expenses were compared within and across the AHCs using community benefits report data. The percentages of the different types of benefits provided and community benefit expenses as part of the total operating expenses were calculated for each hospital. The dollar amount and percentage changes in community benefits from the previous year of available data were calculated.

The content of each KI transcript was coded using NVivo.

A priori codes were created based on topic areas in Healthy People 2020; emergent codes were created and refined during a second-cycle coding until theme saturation was achieved.

Results

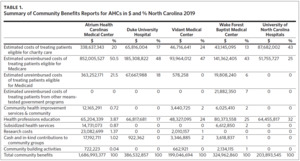

Community Benefits Reports

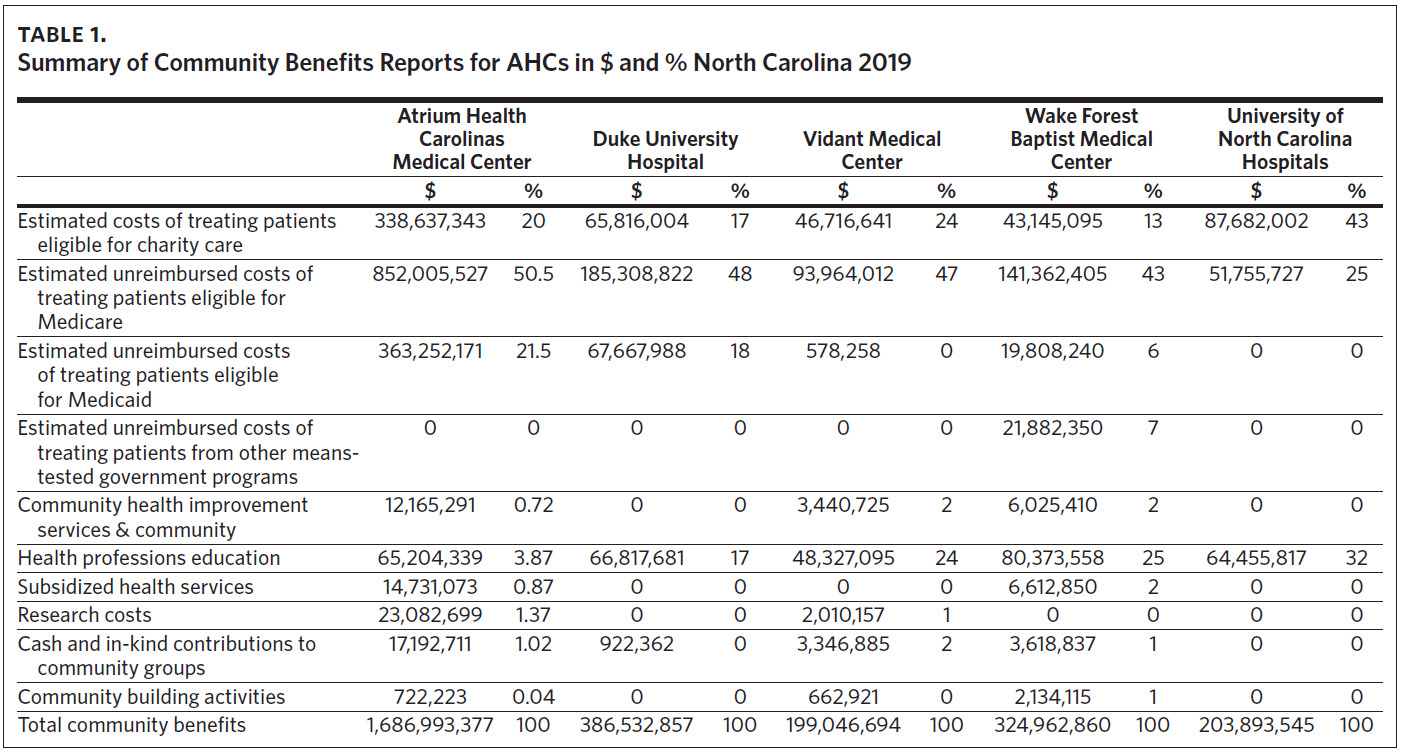

The greatest spending on community benefits is for treating patients eligible for charity care, Medicare, and Medicaid (Table 1), ranging from > $140 million for VMC to > $1.5 billion for CMC. Health professions education ranged between $48 million (VMC) and > $80 million (WFBMC). Community building activities were absent for DUH and UNC, < $700,000 for VMC, ~$700,000 for CMC, and > $2 million for WFBMC.

The costs of treating patients eligible for charity care, unreimbursed costs of treating Medicare, Medicaid, and other means-tested government programs are by far the largest percentage of total community benefits, ranging from 70% to over 90% (Table 1). Health profession education (another leading community benefit) spending ranged from 17% to > 30% for all but one AHC. CMC spent nearly 4% of its community benefit total, which can be explained by a relatively smaller academic footprint compared to the other 4 North Carolina AHCs.

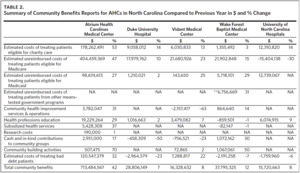

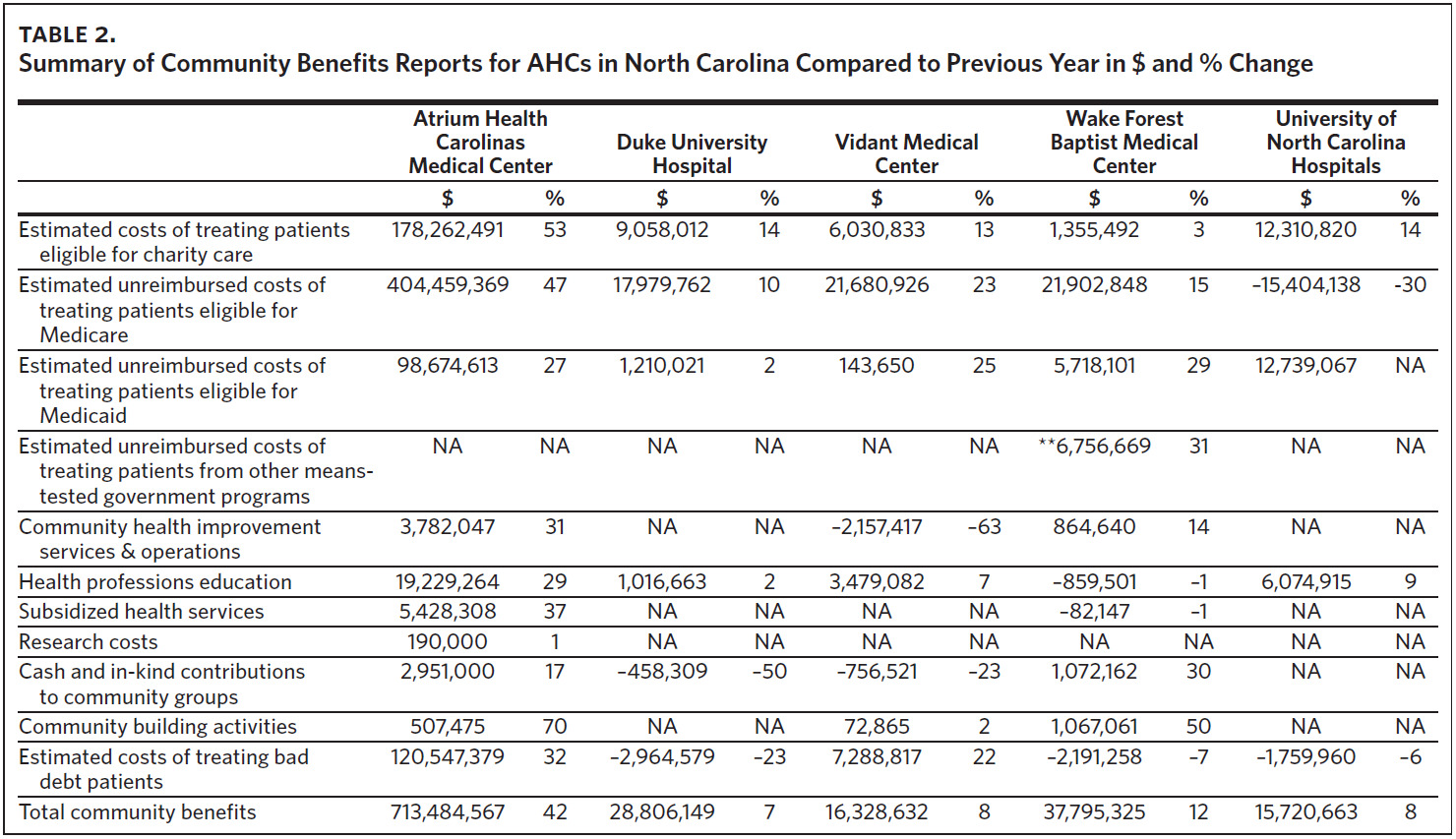

When comparing the itemized benefits changes between 2018 and 2019 (Table 2), all 5 AHCs increased costs for patients eligible for charity care (range: 3%–53%). UNC did not report certain categories for 2019. There were 10%– 47% increases in unreimbursed costs of treating patients eligible for Medicare; only UNC reported a decrease (30%). Increases of 2%–29% for patients eligible for Medicaid were reported. Community health improvement services and operations increased by 14% at WFBMC and 31% at CMC; VMC showed a 64% decrease from 2019 spending compared to 2018. Health professions education increased by 29% at CMC; there were small increases at DUH (2%), VMC (7%), and UNC (9%), and a 1% decrease at WFBMC. Subsidized health services increased only at CMC. Cash and in-kind contributions to community groups decreased at both VMC and DUH and had a modest increase at CMC and WFBMC.

Notably, community-building activities increased 70% at CMC and 50% at WFBMC; however, the total dollar values and percentage of total community benefits were very small, 0.04% and 1%, respectively. WFBMC ( > $1 million) and CMC ( > $500,000) had the largest increases. CMC had the largest increase in both dollars spent ($713 million) and percentage (42%).

KI Interviews

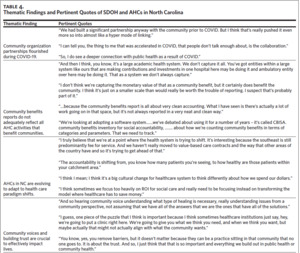

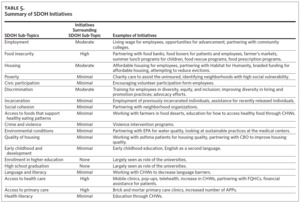

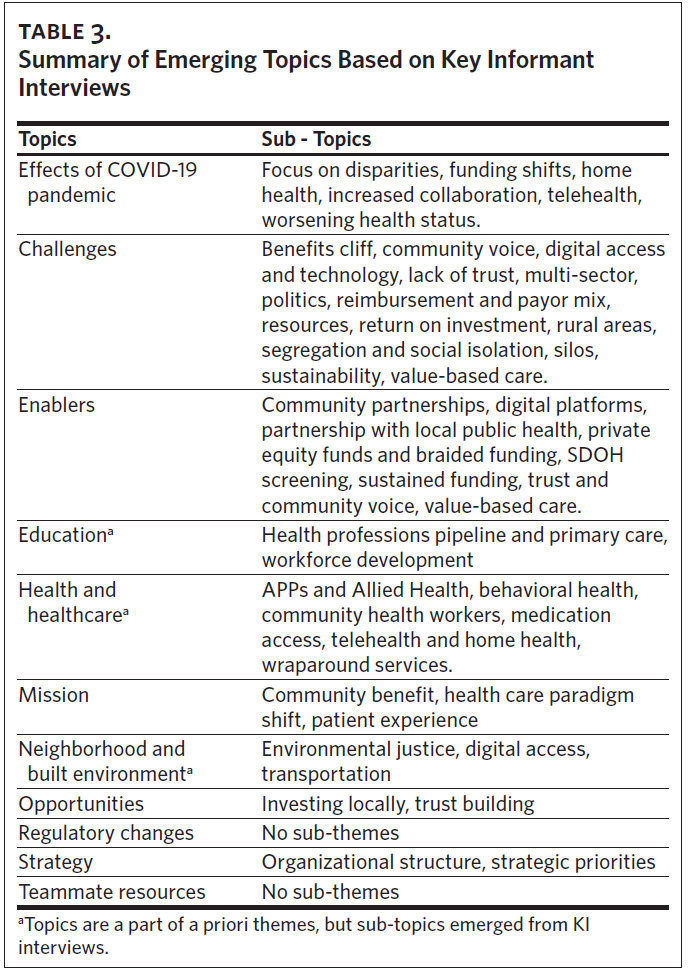

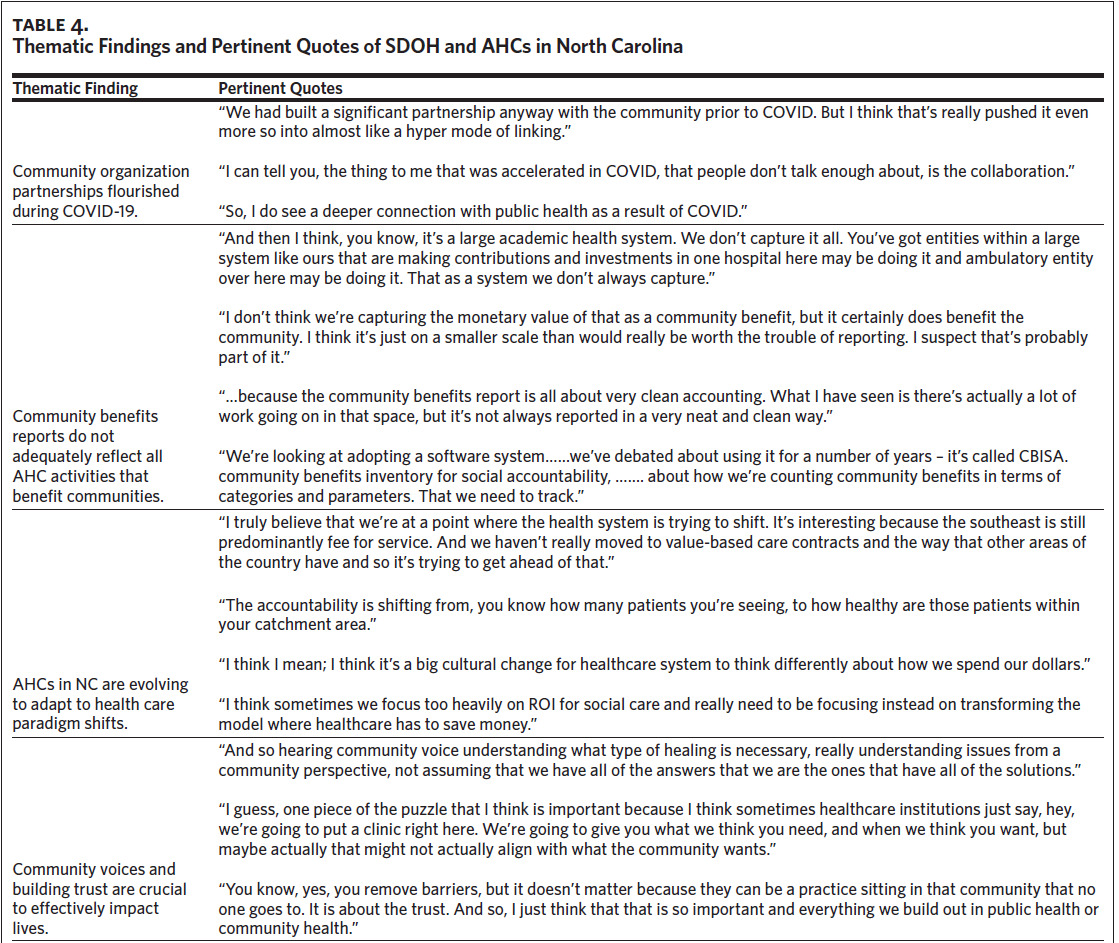

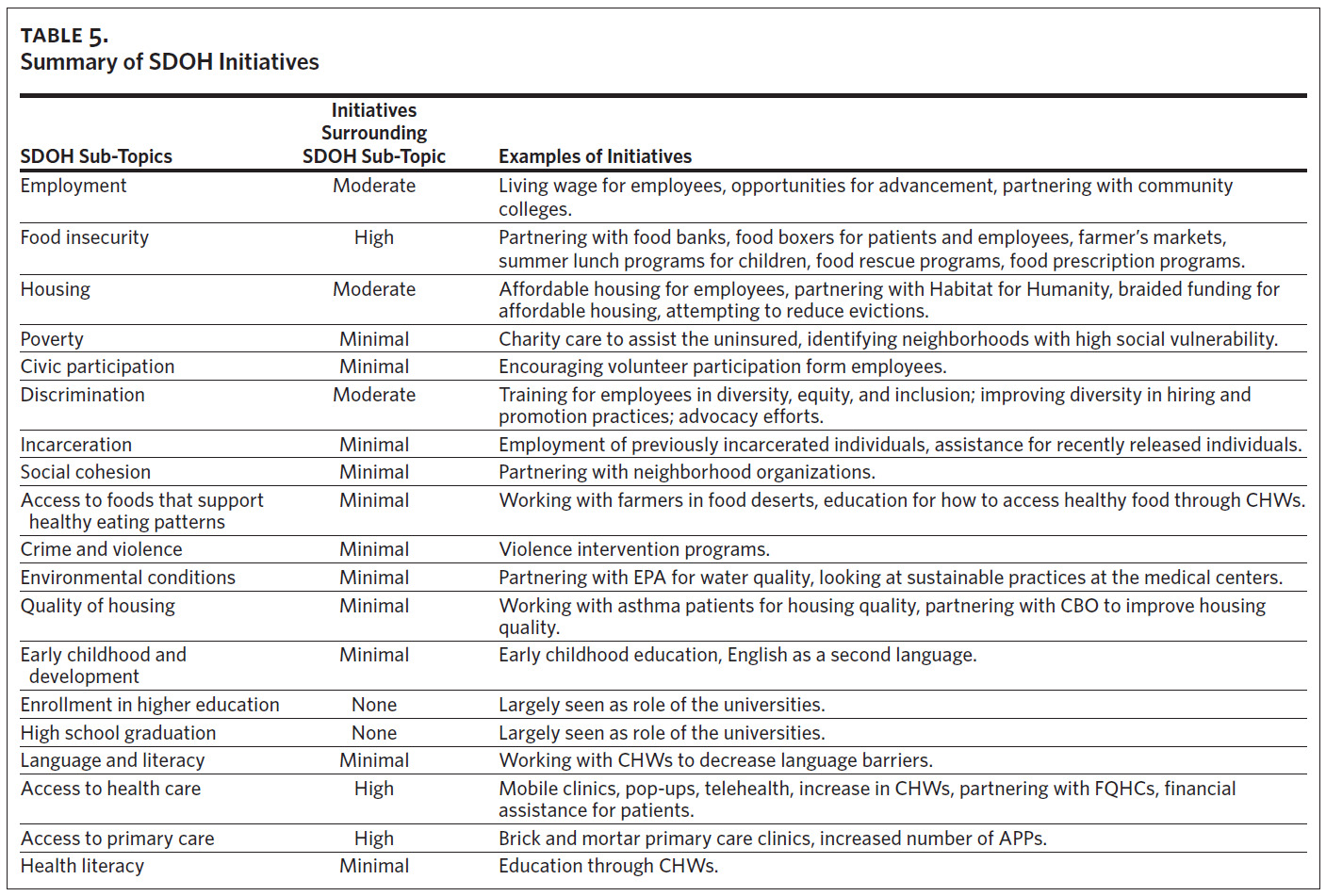

The topics and sub-topics (including challenges and enablers) and thematic findings with pertinent quotes related to SDOH are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. KIs offered several examples of initiatives to address SDOH (Table 5). KIs nearly unanimously voiced the importance of partnering with communities and local public health agencies to address SDOH to improve the health of patients and their communities. AHCs currently partner with local public health agencies through Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), local and state health departments, and various community-based organizations (e.g., food pantries) using community resource hubs or digital platforms. Food insecurity was the primary SDOH identified, with all AHCs investing resources over the last several years. Housing was the second most mentioned SDOH that AHCs attempted to address, with most efforts centered on partnerships with Habitat for Humanity and homeless shelters. Notably, most KIs agreed that AHCs were less able to make a large impact in housing and voiced a desire to do more on this critical statewide and national issue. DUHS invested in housing decades ago and more recently partnered with the county on several affordable housing projects. Atrium also invested in an affordable housing project through partnerships with the Charlotte Housing Opportunity Investment Fund Local Initiatives Support Corporation.11 Several other partnerships and close working relationships with school districts, law enforcement agencies, and faith-based organizations were identified.

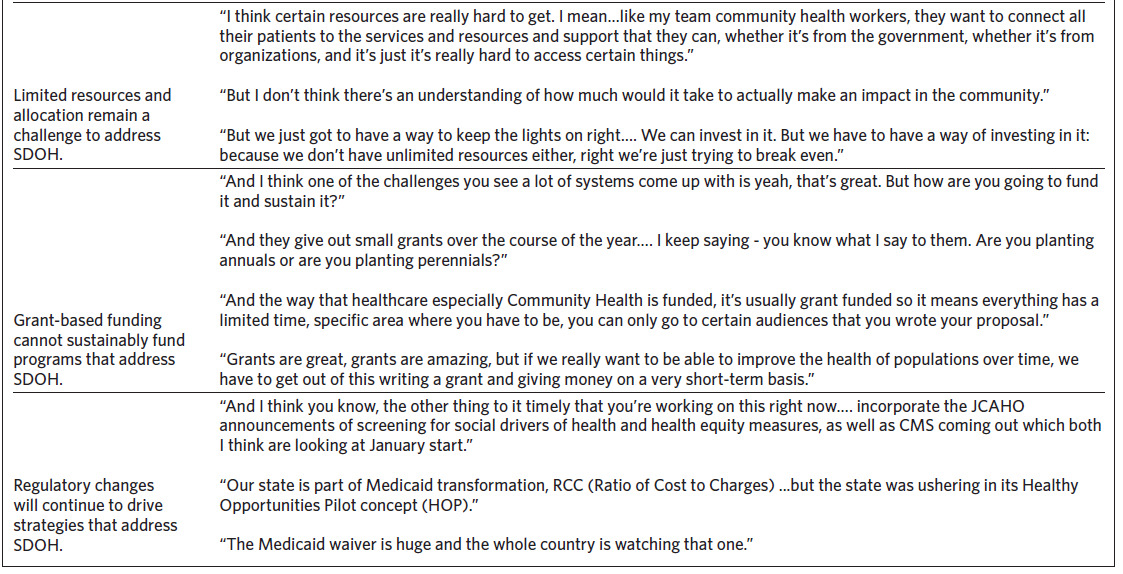

AHCs faced several challenges. Establishing community engagement was crucial, yet difficult. Acknowledging community health workers (CHWs) as a critical link between health care services and community needs, all AHCs increased the number of CHWs when addressing health literacy, access to healthy food, and language barriers. As AHCs sought to increase employees’ wages, employees lost eligibility for public benefits, resulting in lower overall net income (referred to as the benefits cliff). Limited digital access in some areas hindered telehealth services and digital health records access. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed existing health disparities and exacerbated mistrust of the medical community, especially in communities of color. Some SDOH, such as affordable housing, required multi-sector efforts that were deemed beyond AHCs’ capabilities. Local politics and the lack of Medicaid expansion remained huge hurdles. Reimbursement and payor mix during the transition from predominantly fee-for-service to value-based care was also challenging, especially when payors demanded quick fixes for problems requiring long-term investments. KIs also identified as challenges: inadequate staffing, lack of training on how providers can address SDOH, financial constraints, and difficulty demonstrating a return on investment for SDOH interventions. Several KIs noted the need for new metrics demonstrating impact for insurers and health systems, rural digital access, lack of transportation, social isolation, and siloed thinking. Finally, sustainability was a commonly identified challenge due to reliance on grant funding.

KIs identified several enablers, including strong partnerships (especially when addressing food insecurity) and digital platforms such as NCCARE36012 and FindHelp.org that link providers with community resources and local public health agencies; these partnerships were strengthened during COVID-19 vaccination and testing drives. FQHCs were critical to accessing health care for the uninsured. Private equity funds pooled by investors and braided funding (two or more funds coordinated to cover costs and track expenditures) were important for affordable housing efforts. KIs also discussed the potential of different models and what conditions are necessary for enablers to be effective. Atrium’s partnership with Charlotte was mentioned by some KIs from other AHCs as a model that they could emulate. Electronic health records (EHRs) facilitate SDOH screening but must be linked to systems that provide the necessary follow-up for their patients. Sustained corporate funding, rather than grants, was preferred for long-term planning. Building trusting community relationships was crucial. The move toward value-based care was viewed as a challenge by some and an enabler by others. Medicaid’s transformation to a managed care system addressing non-medical factors including transportation, access to healthy food, and stable affordable housing was viewed positively.

Discussion

North Carolina AHCs are grappling with the best way to incorporate SDOH with their overall community benefit strategy. While analysis of available community benefits reports showed very limited spending on community building activities, qualitative interview findings provided insight into a more nuanced picture of current efforts. Some KIs noted a lack of a comprehensive community health strategy across different entities in the system, while others reported a shift to a more centralized form of decision-making. Motivated by improving health access and health equity, all North Carolina AHCs were adopting strategies to invest further upstream. Two key areas for improvement are funding sources for SDOH initiatives and establishing meaningful community partnerships. Adapting to regulatory changes, especially Medicaid transformation and the shift toward value-based care, is critical to achieving this goal.

Funding Sources

Funding challenges persist for SDOH initiatives, and KIs shared concerns that community benefits reports overlook important efforts and contributions by AHCs to enhance community health. These reports indicate that only a small percentage of AHC budgets is allocated to community improvement services and benefit operations. Community benefit dollars are primarily going toward treating patients eligible for charity care and unreimbursed costs of treating Medicare, Medicaid, and other means-tested government programs. Although grants frequently support innovative SDOH initiatives, they often do not provide a sustainable funding stream. KIs also discussed the importance of braided funding with private equity investment, especially for affordable housing. KIs from different AHCs cited Atrium’s 2019 joint effort among Foundation for The Carolinas, the City of Charlotte, corporations, and philanthropic organizations to address affordable housing issues in Charlotte as exemplary.11

Community Partnerships

SDOH screening through EHRs has improved data collection, but connecting patients to appropriate community resources remains challenging. Platforms like NCCARE360 and FindHelp.org are beneficial, but communication with small nonprofit organizations and local health departments that face digital limitations can be difficult and is one of the major challenges with these platforms. KIs observed that building trust and listening to community voices when developing programs is crucial. The COVID-19 pandemic led to the flourishing of community partnerships, especially in personal protective equipment distribution, testing, and vaccination drives. This crisis highlighted the interconnectedness of public health and health care systems, strengthening existing partnerships and sparking new collaborations to address SDOH that were exacerbated by the pandemic-induced economic downturn. The pandemic created opportunities for new partnerships, but whether those will grow or be sustained is uncertain.

Regulatory Agencies

Regulatory changes play a vital role in shaping SDOH initiatives. On January 1, 2023, the Joint Commission created a new standard, highlighting health disparities as a patient safety and quality issue. The second element of performance specifically requires organizations to assess health-related social needs and inform patients about community resources in areas including food insecurity, housing insecurity, and transportation access.13 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reaffirmed its commitment to expanding the collection, reporting, and analysis of standardized data, including SDOH. As part of its Framework for Health Equity for 2022–2032, CMS lists connecting individuals with social services and collecting and leveraging data for underserved communities as 1 of 5 priorities to increase health equity for all individuals.14 Most Medicaid services in North Carolina moved to NC Medicaid Managed Care on July 1, 2021.15 The Healthy Opportunities Initiative specifically addresses SDOH as part of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) mission “of improving the health, safety and well-being of all North Carolinians”.16 The areas of focus are housing stability, food insecurity, transportation access, and interpersonal safety, and include developing a standardized list of screening questions, building a structure to develop and grow the use of CHWs, and developing a statewide map of SDOH indicators to guide priorities.17 NCCARE360 is an important resource to connect patients with identified SDOH needs to community resources.12 NCDHHS has indicated that it would systematically expand the program across the state if shown to improve outcomes and reduce costs.18 The political battle over Medicaid expansion was another important issue at the time the study was conducted. Of particular importance to AHCs with large expenditures on charity care, NCDHHS noted that Medicaid expansion in North Carolina is expected to help with recouping uncompensated costs for the providers caring for uninsured people.18 Notably, NC Medicaid expansion started on October 1, 2023.

Health Care Paradigm Shift

North Carolina AHCs are adapting to evolving paradigm shifts while growing value-based contracts when possible; however, KIs felt that North Carolina and the southeastern United States still primarily operate in a fee-for-service system. Progress is being made with SDOH data collection and strengthening community partnerships. Many grant-funded initiatives on SDOH are led by small numbers of researchers, clinicians, and departments of community health, population health, faith health, and health equity. More recently, Atrium and VMC have created high-level roles focused on SDOH and social needs. However, resource constraints and financial misalignment are barriers to progress.

SDOH Key Areas

Expanding health care access and primary care were universally viewed as a direct responsibility of AHCs through brick-and-mortar expansion, telehealth, and community-based initiatives (e.g., pop-ups, mobile clinics). As major employers, AHCs play a significant role in job creation and poverty reduction. Efforts to combat food insecurity involve collaborations with food pantries, distribution of food boxes, summer meal programs for children, and prescription food programs. Education initiatives were limited to employee tuition reimbursement and incentives, some collaborations around language and literacy, and early childhood education and development. North Carolina AHCs facilitate, but have limited roles in, civic participation and social cohesion efforts. UNC’s North Carolina Formerly Incarcerated Transition (NC FIT) Program expanded to counties where DUH and CMC are located. The program employs CHWs who have a history of incarceration to assist recently released individuals with health care needs.19 Diversity and equity initiatives aim to combat discrimination within AHCs while collaborations with local law enforcement or local government officials seek to address crime and gun violence as part of a broader solution. Housing-related programs, including partnerships with Habitat for Humanity, are ongoing, but the debate of how involved AHCs should be with housing instability and homelessness continues. Some KIs cited Atrium Health Medical Center’s initiative to expand affordable housing as a possible future direction for AHCs.11

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. First, AHC’s community benefits reports are voluntarily submitted and lack important details, making it difficult to ensure that data are accurate and comparable across entities. In addition, limited information was obtained from Form 990. Second, interviewing only 4 stakeholders from each North Carolina AHC and not including community members limits scope and generalizability. KIs were identified by their described role from the AHC websites or personal connections, and other KIs with valuable and pertinent information were invariably excluded. Finally, the first author has spent most of his career in AHC settings, which may provide a deeper understanding of some of the opportunities and challenges AHCs face but may also introduce biases related to the contributions AHCs can make to address SDOH to improve the health of their communities.

Conclusion

The importance of community partnerships and partnering with local public health organizations to address SDOH to improve the health of patients and their communities cannot be overstated. The recent expansion of NC Medicaid will present an opportunity to provide care to more patients but may also accentuate financial and resource constraints. These partnerships were strengthened during the COVID- 19 pandemic. KIs noted that food insecurity and access to health care were the most addressed SDOH. Housing was viewed as a crisis requiring state and national partnerships. KIs also identified several challenges to addressing SDOH, including connecting with and building community trust, digital access, reimbursement, payor mix, and sustaining programs and interventions. Enablers included strong community partnerships, digital platforms connecting patients to services, private equity, and braided funding. The transition to value-based care remains both a challenge and an opportunity for AHCs to address SDOH.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sandra Greene, DrPH; Alexandra Zuber, DrPH; and Michael Flynn, MD, who were part of the dissertation committee for this study.

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

/