The impact of opioid overdoses and other sequelae of criminalized substance use are national health problems in the United States. Pregnant and postpartum individuals are also impacted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that the incidence of births associated with opioid use disorder (OUD, defined as a clinically significant problematic use of opioids) has more than quadrupled from 1999 to 2014 (1.5/1000 deliveries in 1999 to 6.5/1000 deliveries in 2014).1 More recent data suggest that this trend has continued, with a reported 131% increase in deliveries associated with opioid use from 2010 to 2017.2 Previous investigations have found that postpartum is a time of significant risk for return to use and overdose for persons with OUD.3–5 Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), as part of comprehensive substance use disorders treatment, are recommended for at least 1 year postpartum for pregnant people with OUD, in part to protect against a return to use that may lead to overdose. MOUD is available in select settings: office-based opioid treatment, opioid treatment programs, and inpatient or residential treatment centers.

Beyond OUD treatment, perinatal and postpartum patients have a range of other health care needs, such as universal postpartum screening for depression.6 Many postpartum patients also seek contraceptives; the national average rate of contraceptive use in the United States is 60% and trends higher at 89% among people at 0%–149% of the federal poverty level (FPL, a common proxy for low-income status or Medicaid income eligibility).7 Further, hepatitis C screening, testing, and treatment is an area of particular need for pregnant and postpartum OUD patients. From 2000 to 2015, the rate of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection diagnosed prenatally among people with opioid use disorder more than doubled.8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the CDC, the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America all recommend universal HCV screening for all pregnant people.8,9

Despite these well-established needs and recommendations for perinatal and postpartum individuals with OUD, it is well known that access to these health services varies according to race and geographical location.10,11 Further, loss or lack of insurance coverage is directly associated with gaps in care access. For individuals with OUD, Medicaid plays a critical role in facilitating access to health services. Among all non-elderly adults with OUD, 38% have insurance coverage through Medicaid.12 This percentage increases to 55% among low-income non-elderly adults with OUD.12 Among pregnant and postpartum individuals, one study in North Carolina found that over 90% of the patient population at a comprehensive perinatal substance use treatment program had insurance coverage through Medicaid.13 In North Carolina, multiple forms of Medicaid are available to pregnant and postpartum individuals below certain income levels.14 During the time frame of this study evaluation, the following Medicaid parameters were in place: Medicaid for Pregnant Women (MPW) was available to all pregnant individuals with incomes at or below 196% of the FPL during pregnancy, delivery, and for 60 days postpartum14,15; full Medicaid coverage was available to pregnant and non-pregnant individuals at much lower income levels (e.g., ≤ $744 monthly income for a family of 4) or if other eligibility is met (e.g., a qualifying disability or health condition).14 There are no specific coverage time limits for full Medicaid coverage, but access remains contingent on financial status. Family Planning Medicaid, which covered limited family planning health services, is available to individuals with incomes no more than 195% of the FPL.14

The coverage limits of MPW may be problematic for OUD treatment continuation: 1 study found that awareness of likely loss of pregnancy-eligibility Medicaid coverage motivated some perinatal OUD patients’ plans to taper off buprenorphine as soon as possible after delivery, despite medical guidance to the contrary.16 This is significant, as many pregnant and postpartum individuals with OUD have an income below the FPL and rely on Medicaid coverage for perinatal care and OUD treatment. Moreover, access to substance use treatment is a strong predictor of continued recovery.17 However, to date, the impact of MPW on OUD treatment continuation has yet to be described quantitatively. Further, very little evidence exists on the continuation of health care services in the postpartum period among perinatal individuals with OUD.9

The purpose of this study was to assess the access to and continuation of OUD treatment and postpartum health care services among Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with OUD prenatally. We specifically examined the impact of Medicaid coverage status (MPW versus other forms of Medicaid) on the rates of utilization. We hypothesized that individuals with MPW would experience lower rates of postpartum health care utilization due to MPW coverage limits. As secondary exposures, we sought to understand the relative impact that race, geography (urban versus rural), and prenatal access to MOUD had on the postpartum utilization of health services. These secondary exposures served to provide a greater understanding of the magnitude that systemic social barriers may have.

Methods

This study used a historical cohort design with de-identified medical and pharmacy NC Medicaid claims data. The observation period for this study was October 1, 2015, through March 30, 2019. The index date was the date of delivery. The earliest index date available for inclusion in the cohort was July 1, 2016, to allow for a 9-month pre-index date, and the latest was March 30, 2018, to allow 12 months of follow-up.

Criteria for inclusion were individuals enrolled in the NC Medicaid program at the time of delivery, a diagnosis of OUD during the pre-index period or as part of the delivery encounter (as evidenced by F11, F19, or relevant T40 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] diagnosis codes), a singleton pregnancy, and evidence of a live delivery. Based on previous literature, live delivery was identified through Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and the ICD-10-PCS translation of the ICD-9 procedure codes.18

The primary outcomes were types of postpartum health care utilization, including the number of health care encounters, number of claims and date of last claim for MOUD (buprenorphine [monoproduct or combined with naloxone captured via national drug codes (NDC)]19 and methadone [captured through professional billing codes]), evidence of contraception use (identified through NDC or professional billing codes), hepatitis C screening or treatment, and depression screening or antidepressant treatment.

The primary exposure of interest was the type of Medicaid coverage (MPW versus other types of Medicaid coverage). To conservatively estimate the impact of MPW, individuals were classified as having MPW even if they later transitioned to other forms of Medicaid coverage (e.g., Family Planning Medicaid). Other exposures of interests included receiving MOUD treatment prenatally (yes/no), racial/ethnic strata (White versus a composite of individuals of other racial and ethnic minority groups), and urban versus rural residence (as indicated by residence zip code and coded using the rural-urban commuting area [RUCA] classification C codes).20

Demographic characteristics such as age, race, and urban versus rural residence were captured via the member file. Common maternal diagnoses (e.g., gestational diabetes, depression, asthma, obesity, and hypertension), mental health diagnoses (e.g., bipolar disorder, adjustment disorder, depression, anxiety), as well as concurrent substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol use disorder, amphetamine use disorder, cocaine use disorder) were gathered during the 9-month period prior to and including the index date, as available using ICD-10-CM billing codes. Medications were identified through NDC in pharmacy claims data. Medications captured included antidepressant medications (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants), antiemetics, pain medications, antibiotics, and immunizations (influenza and Tdap). Other prenatal health care utilization, including number of health care visits prenatally (defined as the number of unique encounters), and hepatitis C screening/treatment were also captured. Delivery outcomes were gathered on all patients as recorded by delivery-related claims, including preterm labor, cesarean delivery, and other delivery complications (e.g., breech position, placenta previa, postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma). Additionally, a maternal comorbidity index, as outlined by Bateman and colleagues,21 was used to assess overall maternal health, as this may affect utilization.

Persons eligible for inclusion were followed in time from their index date. Persons no longer retaining Medicaid coverage in postpartum were censored. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile range [IQR]) characterized the baseline characteristics and health care utilization during the postpartum period. Discontinuation of MOUD (buprenorphine products or methadone), defined as the last claim during the 12 months postpartum for those with evidence of MOUD use during postpartum, was stratified by exposure and assessed with Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. All data were analyzed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). This study was reviewed and determined exempt by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

Results

Sample Characteristics

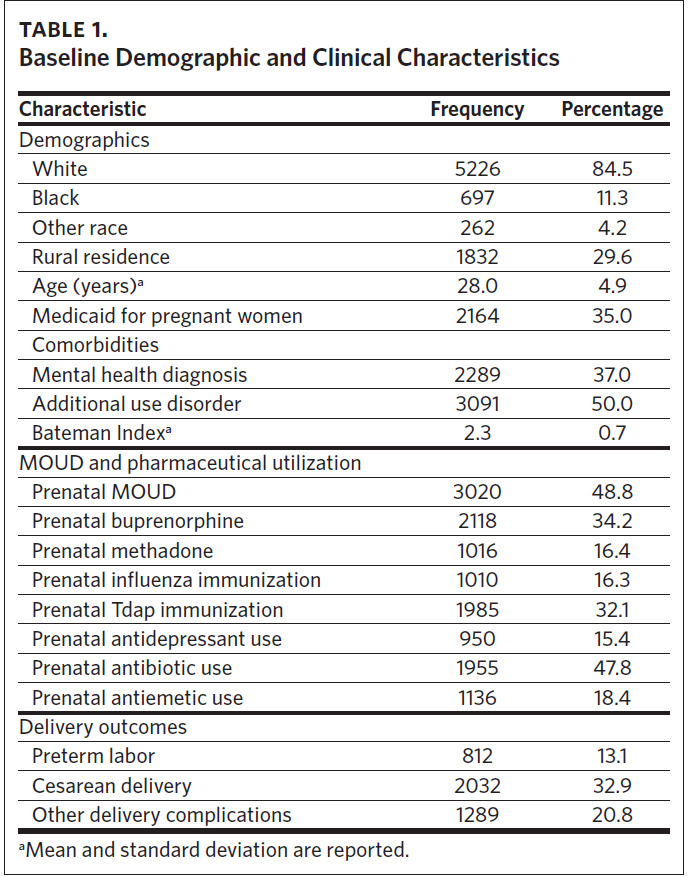

There were 6,186 individuals who met the criteria. Of those included, 84.5% were identified as White, 29.6% lived in rural areas, the average age was 28 (standard deviation: 4.9), and 35.0% of individuals had MPW.

Of those in the sample, 37.0% had a concurrent mental health diagnosis, with depression (23.0%) and bipolar (10.6%) being the most prevalent two. Moreover, nearly half (49.9%) had a concurrent substance use disorder, with tobacco (27.5%) and cannabis (18.8%) being the most common. Table 1 contains more details.

Nearly half (48.8%) of individuals had evidence of MOUD utilization prenatally, with 34.2% receiving buprenorphine and 16.4% receiving methadone. Regarding other pharmacotherapy use, 47.8% had a claim for antibiotics, 18.4% for antiemetics, and 15.4% for antidepressants. Nearly one-third of the individuals (32.1%) had evidence for Tdap vaccination and 16.3% for influenza vaccination.

Health Care Utilization Postpartum

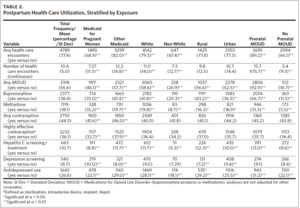

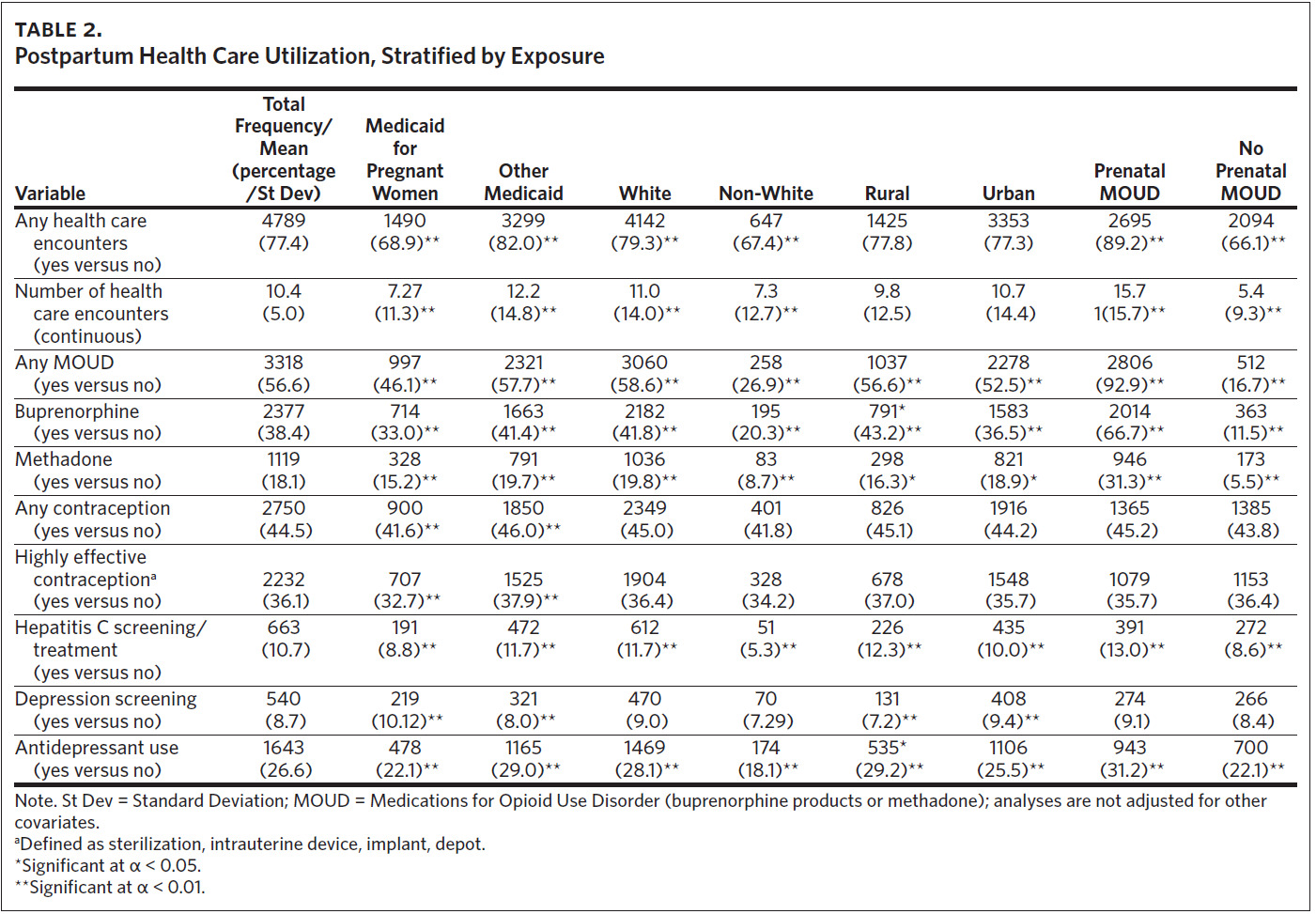

In the study population, 4,789 individuals (77.4%) had evidence of any health care utilization during postpartum. Of those individuals, the median number of encounters was 5 (average: 10.4 encounters) with an IQR of 12. The last health care encounter occurred, on average, 248 days post-delivery (median: 300 days). For other postpartum health care utilization, 10.7% had evidence for hepatitis C screening or treatment, 44.5% had evidence of any contraception use (with 36.1% having evidence for sterilization, depot, implant, or IUD methods), and 8.3% for a depression screening (26.6% of all individuals had evidence for antidepressant use during postpartum). Table 2 contains more details.

Stratified by exposure groups, individuals with MPW had significantly lower rates of health care utilization in all categories as compared to those with other forms of Medicaid. Non-White individuals had significantly lower rates of health care utilization except for contraception use and depression screenings. Individuals in rural areas had significantly higher rates of MOUD use, hepatitis C screenings, and antidepressant use but lower rates of depression screening. Individuals with evidence of prenatal MOUD use had significantly higher rates of health care utilization except for contraception and depression screenings. Table 2 contains more details.

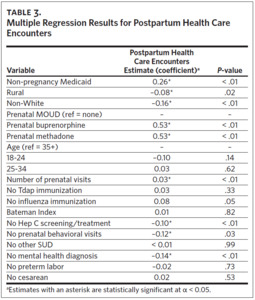

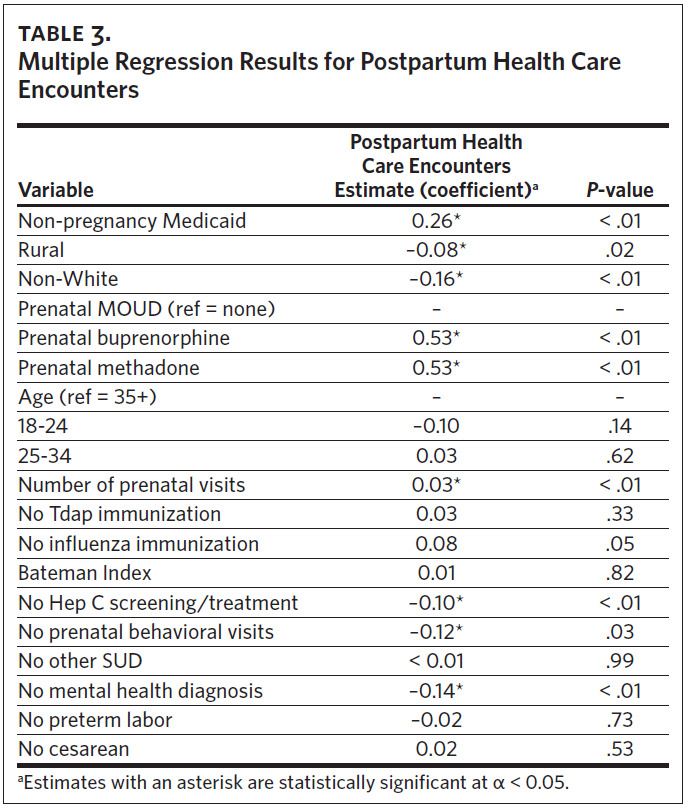

Postpartum Health Care Visit Predictors

In the multiple negative binomial regression model regressing on the number of postpartum health care visits, the most significant predictors were living in a rural area (effect estimate [EE]: –0.08; incident rate ratio [IRR]: 0.93), being in the non-White racial category (EE: –0.16; IRR: 0.85), having other types of Medicaid (EE: 0.26; IRR: 1.30), receiving buprenorphine (EE: 0.53; IRR: 1.70) or methadone (EE: 0.53; IRR: 1.70) prenatally, the number of prenatal visits (EE: 0.03; IRR: 1.03), and having no concurrent mental health diagnoses (EE: –0.14; IRR: 0.87). Table 3 contains complete model results.

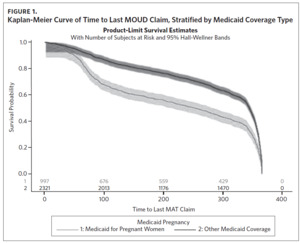

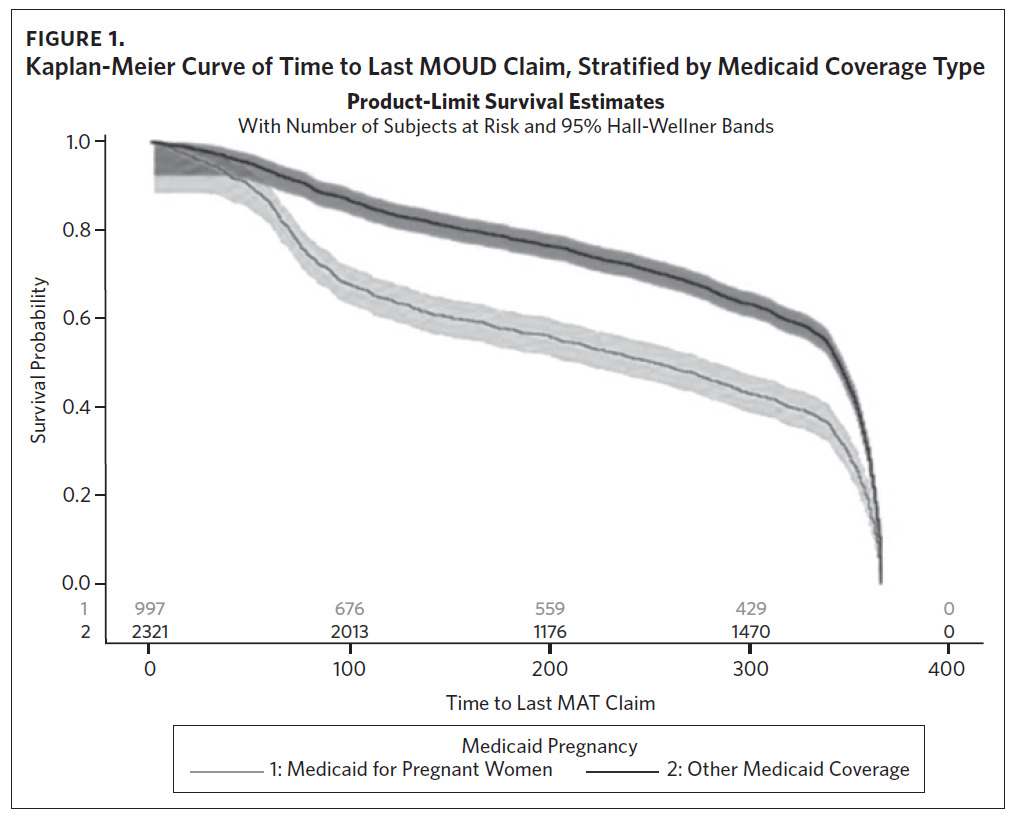

For the continuation of MOUD use postpartum, there were significant differences in the stratified Kaplan- Meier curves for the type of Medicaid (MPW versus other Medicaid coverage, log-rank test P-value < .0001, Figure 1), race (White versus non-White, log-rank rest P-value = .02, Supplemental Figure 1), and the type of MOUD (buprenorphine versus methadone, log-rank test P-value < .0001, Supplemental Figure 2). No differences were seen across rural versus urban strata (Supplemental Figure 3). For the Medicaid coverage stratification, 85% of individuals with MPW had evidence of MOUD continuation by 60 days postpartum compared to 93% for individuals with other types of Medicaid coverage. This drops to approximately 71% by 90 days and 58% by 180 days postpartum for individuals with MPW compared to 88% and 78% by 90 and 180 days, respectively, for individuals with other types of Medicaid. For individuals identified as White, 91%, 83%, 72%, and 62% had evidence of continuation at 60, 90, 180, and 270 days. For individuals identified as racial or ethnic minorities, 89%, 83%, 73%, and 64% had evidence of continuation at 60, 90, 180, and 270 days, respectively. For stratification by type of MOUD, the curves are similar until after approximately 330 days, at which point buprenorphine continuation tapers off at a faster rate than methadone.

Discussion

Postpartum individuals with OUD require continuity of OUD treatment and other health care services during at least the first 12 months after delivery. It is critical to understand the current gaps in care to identify appropriate interventions to prevent adverse outcomes and promote stable recovery. This study found that there were disparities in utilization across exposure strata. Specifically, individuals with MPW, who were individuals of racial and ethnic minority groups, lived in rural areas, and had no evidence of prenatal MOUD, had lower rates of health care utilization.

Findings from our study are consistent with published data by Ahrens and colleagues, who found similar rates of cesarean section deliveries, use of antidepressants prenatally, and age distribution among perinatal patients with OUD in Vermont and Maine.22Further, rates of prenatal use of MOUD were approximately the same as ours (35%– 41% versus 34% for buprenorphine products and 9%–21% versus 16% for methadone, respectively).22 The rate of co-occurring mental health diagnosis in our population is lower compared to the 2017 self-reported mental illness rates of 52% across women of reproductive age (18–49) and compared to the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which reports that 48% of adults (both male and female) over 18 years of age with a substance use disorder have a co-occurring mental illness.23 This suggests that mental health illness may be either underdiagnosed or underreported and thus not detected in the study population.

In this analysis, we found that 77% of individuals had at least some evidence of postpartum health care utilization, with a median number of 5 visits among those with evidence. This is similar to the rate of a general Medicaid population (81%) and points to the challenges that many postpartum individuals encounter when seeking health care services or continuing treatment for opioid use.24 Specifically, previous literature has found that health care deserts, childcare, transportation, employment conflicts, and changes in insurance coverage, among other issues, may impede access and disrupt treatment.25,26 Furthermore, many pregnant individuals with OUD report experiencing stigma from providers and fear of losing custody of their child from the department of social services, resulting in a greater tendency to avoid interacting with the health care system.26,27

We also found that there were significant differences in the number of visits between those with MPW versus other types of Medicaid. Having other forms of Medicaid as a positive predictor of the number of postpartum health care visits as well as the number of claims for MOUD confirms that the loss of Medicaid disrupts access to care and that Medicaid continuation in the form of eligibility for other types of Medicaid or Medicaid expansion could increase continuity of care.28 However, we were somewhat surprised to find that among those with any health care utilization, the last health care visit took place about 8 months postpartum, on average. Based on the findings of regional and local studies conducted in and around rural parts of North Carolina, we anticipated that many postpartum people with OUD would lose access to healthcare due to MPW coverage ending approximately 2 months after delivery. This finding suggests other types of Medicaid coverage, such as Family Planning Medicaid and full Medicaid, played a larger role in facilitating access to health care services than previously understood. This is an important finding, as we know from previous research that opioid-related overdose deaths peak at approximately 7–12 months postpartum.29 Future investigations should aim to determine the impact that changes in Medicaid coverage, particularly in states that have not expanded Medicaid, have on opioid-related overdose.

Our study found that postpartum use of MOUD varied greatly according to demographic strata and prenatal MOUD use. Our findings are confirmed by previous studies that found concentrations of buprenorphine treatment among White and privately insured or self-paying patients, in North Carolina and nationally.30–33 Goedel and colleagues reported that an increase in the proportion of African American or Hispanic/Latino individuals in a community results in a decrease in the number of facilities available to offer methadone or buprenorphine treatment. Disparities in OUD treatment by race and ethnicity are also found specifically for perinatal OUD patients. Schiff and colleagues found that Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino patients have 76% and 66% lower odds of continuing treatment as compared to White individuals, respectively .10

The largest disparity in postpartum MOUD was among individuals with versus without prenatal evidence of MOUD use. Likewise, the finding that the number of prenatal visits positively predicted more postpartum health care visits appears to confirm other studies that establishing care with a known and trusted provider prenatally increases the likelihood that a pregnant person with OUD will continue attending care and receiving important treatment services after delivery.34,35 Providers knowing their patients’ experiences and concerns beyond clinical needs is important for addressing concerns and ensuring continuity of care despite patients’ ambivalence or fear.

The finding that just over 10% had claims entered for hepatitis C screening is troubling given universal hepatitis C screening in pregnancy recommendations and the current understanding that 60%–75% of people with OUD likely have chronic hepatitis C that can be safely treated postpartum. Our data suggest that this remains a gap, even when including the percentage of individuals who received a screening during pregnancy (22.8%).

At 44%, subjects in this Medicaid claims sample had a lower rate of contraceptive use than the national United States average for postpartum individuals (88%).36 However, among individuals with opioid and other substance use disorders, rates of postpartum contraceptive use have been shown to vary and are typically lower, ranging from 25% to 74%.37 Of the types of contraceptives, oral contraceptives, the long-acting depot, and intrauterine devices/implants were the most utilized. Unintended pregnancy rates among individuals with OUD have been estimated at 86% and short pregnancy intervals at 20%.38,39 Our data suggest that interventions centered around reproductive health and justice continue to be a priority need for patients and care providers.

In this study, we found lower than expected rates of postpartum depression screenings. Previous research suggests that 87% of patients with a postpartum visit are asked about depression.40 The low rates of postpartum depression screening may be due to a number a factors including bundled billing services or screening performed during pediatric encounters, both of which would not be evident in our dataset.41 Perinatal clinicians are recommended to perform screening for perinatal mood disorders at entrance into perinatal care as well as in the postpartum period, and our data reports that screenings may be underperformed, although additional analyses with more robust data would be needed to confirm this. As many as 1 in 8 women (12.5%) in the United States report experiencing symptoms of depression during the first year postpartum; from 2015 to 2018, an estimated 17.7% of women in the United States used an antidepressant.40,42,43 Even in patients who are already diagnosed with a mental illness and/or are on pharmacotherapy, it remains the evidence-based recommendation to perform depression and anxiety screening with a validated tool.6

It is unsurprising that living in a rural area and being non-White were each predictors of a lower number of postpartum health care visits; for each of these populations, difficulty of access to postpartum care overall, OUD care overall, and postpartum OUD care specifically is well-supported in existing literature.24,44,45 Postpartum OUD patients specifically in rural parts of Western North Carolina have previously reported challenges related to transportation, loss of MPW, and stigma, affecting their ability to attend postpartum visits.16 Our claims analysis reinforces these findings across the state and suggests these challenges are less of an issue for postpartum OUD patients in more urban settings.

Strengths and Limitations

This analysis leveraged claims data from a state Medicaid program to follow postpartum individuals with opioid use disorder. Although we were able to examine many health care services among subpopulations, there are some notable limitations to this analysis.

We defined one of our primary exposures as having MPW during pregnancy or postpartum. By using this definition, we are likely misclassifying the real exposure for many individuals and thus potentially underestimating the effect that having MPW has on postpartum health care utilization as some beneficiaries may ultimately qualify for other types of coverage and thus may not experience the same limitations. This renders our results conservative. Future investigations should parse out the impact that MPW in non-expansion states has on health care access during postpartum.

Similarly, we defined another primary exposure, rural versus urban, using RUCA codes. While this gives an important insight into the differential healthcare utilization based on rural versus urban status, there are regional differences in health care resources in rural areas.45 This analysis did not allow us to examine these differences.

For MOUD utilization, we used the last date of evidence to show continuation. Defining this measure as such provides an important insight into how long into postpartum individuals were able to continue having coverage for MOUD. However, this measure does not provide information on the level of adherence or gaps in use. Future analyses should examine factors associated with adherence to MOUD, as this has important clinical implications for the recovery of perinatal patients with OUD. Moreover, we were not able to determine whether discontinuation was indicated according to the care plan or due to treatment barriers.

We do not know if or how individuals who appear to underutilize health care services, such as MOUD, in fact obtain needed care following the loss of Medicaid coverage. It is therefore expected that our estimates on utilization may be conservative. Despite this limitation, the results of this analysis provide an important insight into the health care utilization of individuals with OUD across demographic and treatment strata during the postpartum period.

We used medical and pharmacy claims from a limited timeframe to identify maternal comorbidities, pharmacotherapy use, and postpartum health care utilization. As is the case with claims data, these data will not provide insight into the severity of the disease, as would other types of data (e.g., survey-based measures). This is important, as OUD symptoms and treatments may vary in intensity and duration depending on the severity of the condition. Additionally, these data were captured pre-COVID-19 as synthetic illicit opioid use (fentanyl) was rising and rural access to prenatal care was shifting across the state. The impact of the current landscape on perinatal OUD warrants additional evaluation.46,47

Similarly, health-related quality of life, an important measure to understand the overall health care status of an individual, was not available with these data. Further, health care systems have had, to varying degrees, growth surrounding education about best practices related to perinatal substance use disorders.45 Thus, screening and treatment practices, as well as resources for patients, may have changed since the study timeframe. Finally, the claims data obtained may not be generalizable to other populations nor to populations in states with expanded Medicaid coverage. Starting on April 1, 2022, North Carolina expanded Medicaid coverage of postpartum services for 12 months instead of the previous 60-day limit.48 Thus, future research is warranted to examine the nuances of these findings and their applicability to other populations.

Conclusion

In summary, data from this study suggest that significant gaps in postpartum health care use remain across types of Medicaid coverage, race, geographic setting, and prenatal care access. In particular, unstable Medicaid coverage may significantly disrupt OUD treatment continuity. Facilitating access to OUD treatment by prioritizing Medicaid and, more generally, insurance coverage is crucial for the physical and social wellbeing of perinatal populations and their families.

Acknowledgments

The findings in this manuscript were previously presented at the 53rd Annual Conference for the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Financial support

This study was supported by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Health Benefits.