Introduction

Ensuring access to oral health care services in North Carolina requires an adequately trained and distributed workforce. In 2022, there were 5,887 active dentists and 6,474 active dental hygienists in North Carolina, accounting for 5.5 dentists and 6.1 dental hygienists per 10,000 population. Between 2005 and 2022, North Carolina moved from 47th in the nation in dentist supply relative to population to 24th.1 However, more than 50% of all active dentists in 2022 practiced in six of the state’s 100 counties.

Analyses for this study examined active North Carolina dentist and dental hygienist licensure data as of October 31, 2022. Data were collected by the North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners and housed in the North Carolina Health Professions Data System. Analyses used descriptive, bivariate, and general linear modeling methods to estimate differences in demographics, practice location, practice setting, and education patterns among the oral health workforce in North Carolina. The licensure data do not include Medicaid participation and the race/ethnicity categorization limited the possible comparisons between the state’s population and its oral health workforce.

Background

Oral health is an essential component of overall health and well-being. In 2000, the US Surgeon General released the first report highlighting oral health and a “silent epidemic” of oral disease that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, such as those of low socioeconomic status (SES), racial/ethnic minorities, and the elderly.2 In North Carolina, lack of access to oral health care has widened disparities for adults over age 65, as this population has lower rates of preventive care and higher rates of untreated tooth decay and tooth loss.3,4 North Carolinians residing in rural areas are especially vulnerable to oral health disparities due to the lack of fluoridated water resulting in higher rates of periodontal disease and dental caries.5,6 Moreover, both national and North Carolina data consistently indicate that racial/ethnic minorities have higher rates of periodontal disease compared to their White counterparts and that periodontitis is associated with other chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.5 These disparities are compounded by social risk factors including lower SES, lack of access to oral health care, food insecurity, structural racism, and discrimination.5,7 Given North Carolina’s aging population, a relatively large percent of residents in rural areas, and the growing racial/ethnic minority populations in the state’s population, it is vital to track the supply of oral health clinicians to ensure timely and routine oral health care access for all.8

North Carolina’s rapid population growth and changing age and racial/ethnic demographics increase the demand for all health care services, including oral health services. North Carolina is the ninth most populous state in the United States.9 The older adult population in North Carolina is growing at twice the rate of the state’s general population10; the concentration of older adults in underserved areas of the state is notable, with 38% of the population aged 65 and older residing within North Carolina’s 70 rural counties.11 The racial/ethnic structure of the state’s population has changed. Between 2020 and 2023, the percent of the population identifying as Hispanic increased from 4.8% to 11.4% and the percent identifying as Asian increased from 1.5% to 3.6%, whereas the percent of the population identifying as White decreased from 70.2% to 60.7% and the percent identifying as Black or African American remained constant at approximately 21%.12,13

Nationally, 58 million people live in one of the country’s 6,860 Dental Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). North Carolina has 188 Dental HPSAs,14 and all 100 counties are either partially or fully designated as Dental HPSAs by the US Health Resource and Services Administration.15 A previous analysis conducted in 2001 of the state’s oral health workforce found that North Carolina ranked 47th out of 50 states in the dentist-to-population ratio, and had 4.7 dentists per 10,000 population in North Carolina compared to 5.8 dentists per 10,000 population in the United States.16

Recognizing the need to improve access to oral health care, the North Carolina Institute of Medicine (NCIOM) convened an Oral Health Transformation Task Force in August 2022. The vision of the task force is, “a patient-centered future for oral health in North Carolina, in which oral health care is redefined as comprehensive and seamlessly integrated with overall health”.17 The task force published a report in April 2024, Transforming Oral Health Care in North Carolina, that called for improving the supply, distribution, and diversity of the oral health workforce (dentists, hygienists, and dental assistants) with a focus on Medicaid-serving and rural practices.17 Improved data collection, monitoring, and analysis of oral health trends and the oral health workforce are key components of the report. The report directs the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Division of Public Health Oral Health Section to facilitate collaboration between several North Carolina partners, including the UNC Sheps Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, to synthesize clinical, payment, workforce, and public health data in a central location for researchers, payers, and practitioners to access the information.17

This study aims to respond to recommendations outlined within the Oral Health Transformation Task Force report by providing recent data on North Carolina’s oral health workforce, including the supply and distribution, educational trends, and racial/ethnic composition of the workforce compared to the state’s population. Data on the oral health workforce are essential for education systems, policymakers, and the oral health care delivery system to effectively respond to gaps in care and evaluate oral health care delivery models, such as loan repayment programs, other incentives,18 and interprofessional collaboration.19,20

Methods

This study analyzed dentist and dental hygienist licensure data collected by the North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners during initial licensure and subsequent licensure renewal processes. Data include active, in-state dentists and dental hygienists as of October 31, 2022. Data are self-reported and clinician location is based on primary practice address. Licensure data are cleaned and housed in the North Carolina Health Professions Data System (HPDS), administratively located in and maintained by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The HPDS is supported by the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (NC AHEC) Program.

North Carolina population data were obtained from the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management (OSBM).21 County estimates are based on primary practice location. Metropolitan and nonmetropolitan county status were defined using US Office of Management and Budget Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs). Nonmetropolitan counties include micropolitan counties and non-CBSAs. CBSA definitions used in the analysis to assign counties to metropolitan and nonmetropolitan status vary by year of data. That is, the counties defined as nonmetropolitan in 2000 are different than the nonmetropolitan ones in 2017.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses for this study used descriptive, bivariate, and general linear modeling (GLM) statistical methods to estimate differences in demographics, practice location, practice setting, and education patterns among the oral health workforce in North Carolina. Study findings were considered statistically significant if the p value was < .05. All analyses were conducted in R Core Team (2023).22

Results

In 2022, there were 5,887 active dentists and 6,474 active dental hygienists in North Carolina.23 The majority (64%) of the dentist workforce was male and the dental hygienist workforce was mostly female (98%). The average age of dentists was 46.9 years, and the average age of dental hygienists was 42.9 years in 2022.

From 2000 to 2022, the total number of dentists in North Carolina increased by 82.5% (3,225 to 5,887); the total number of dental hygienists increased by 76.5% (3,669 to 6,474). North Carolina’s dentists per capita increased from 4.0 dentists per 10,000 population in 2000 to 5.5 dentists per 10,000 population in 2022.23 The dental hygienist per capita ratio in North Carolina increased from 4.5 dental hygienists per 10,000 population in 2000 to 6.1 per 10,000 population in 2022.23

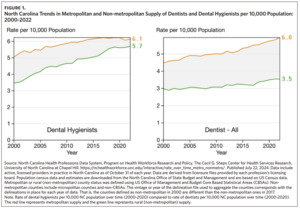

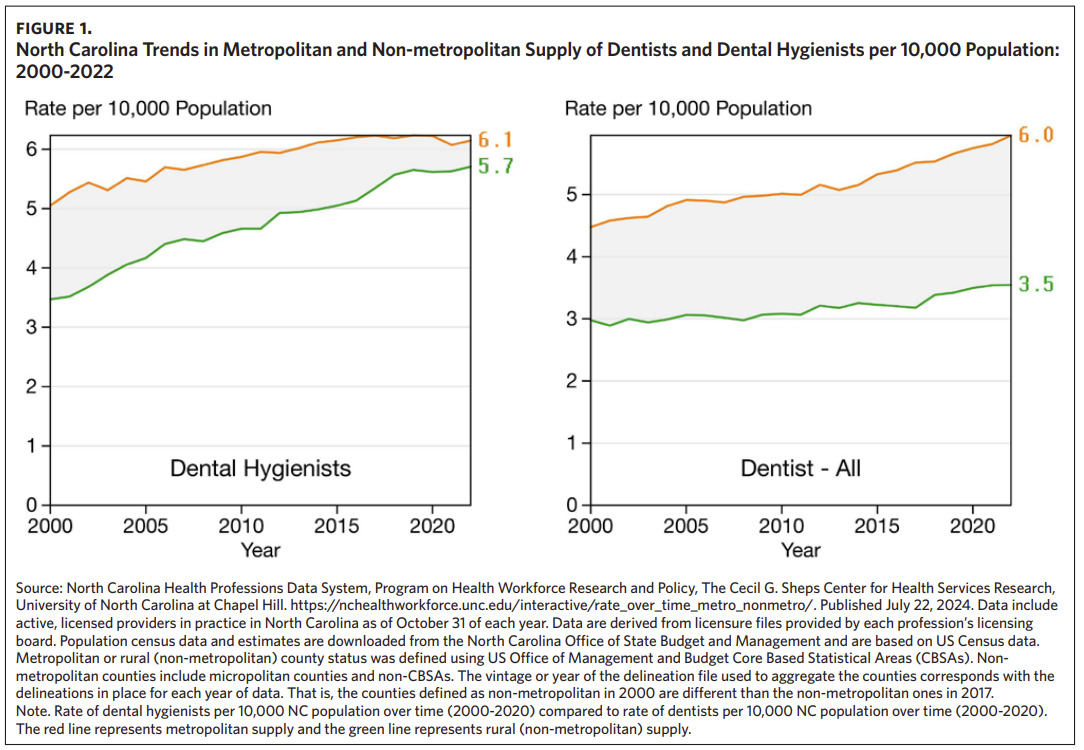

North Carolina Distribution of Dentists and Dental Hygienists

In 2000, the ratio of North Carolina dentists per 10,000 population was 3.0 in nonmetropolitan and 4.5 in metropolitan counties, while the ratio of dental hygienists per 10,000 population was 3.4 and 5.1 in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties, respectively. Between 2000 and 2022, the gap in the supply of dentists per 10,000 population in nonmetropolitan versus metropolitan counties became larger while the gap in the supply of dental hygienists narrowed. Specifically, by 2022, the gap in the ratio of dentists per 10,000 population grew to 3.5 and 6.0, respectively, between nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties while the gap in the ratio of dental hygienists per 10,000 population narrowed to 5.7 and 6.1, respectively (Figure 1). We found a relationship between the type of clinician (dental hygienist or dentist) and the location of the practitioner in a metropolitan or nonmetropolitan county (X2 = 72.00, p < .0001). In nonmetropolitan counties, the ratio of dental hygienists to dentists was 1.61 (1,099/681) compared to 0.97 (5,206/5,378) in metropolitan counties.

Among the 5,887 active North Carolina dentists in 2022, more than 50% practiced in six counties: Wake (n = 1,009; 17.2%), Mecklenburg (n = 926; 15.7%), Guilford (n = 331; 5.6%), Orange (n = 278; 4.7%), Durham (n = 235; 4.0%), and Forsyth (n = 226; 3.8%). Among these six counties, the average ratio of dentists was 3.59 per 10,000 population in 2022, which was a decrease from the average ratio of 6.67 dentists per 10,000 population in 2012. In addition to the maldistribution of dentists in North Carolina, this ratio decrease from 2012 to 2022 demonstrates that the active number of dentists is not increasing at the necessary rate to offset the population growth.

To examine the difference between state population and supply of dentists, we examined a five-year trend from 2017 to 2021. Between 2017 and 2021, North Carolina added 586 dentists to the workforce. Among these 586 dentists, 60% went to five counties that represent 31% of the state’s population: Durham, Guilford, Mecklenburg, Pitt, and Wake (Figure 2). Another five counties received 20% of dentists: Brunswick, Moore, New Hanover, Orange, and Union. These counties represent 8% of the state’s population. Taken together, these trends mean that 39% of the state’s population received the majority of dentists (80%), while 61% of the population living in 90 counties in North Carolina only saw 20% of this growth in new dentists (Figure 2).

Figure 3 compares the racial/ethnic distribution of North Carolina’s active dentists and dental hygienists in 2012 and in 2022 to the state’s population. The oral health workforce is not keeping pace with the increasing diversity of the North Carolina population. Between 2012 and 2022, the percentage of the state’s population that identified as Black held steady at about 21% of the population while the percentage of dentists identifying as Black increased from 8.6% to 9.1% of the workforce, and the percentage of dental hygienists identifying as Black increased from 3.9% to 5.0% of the workforce. The Hispanic population in North Carolina grew from 9.1% to 11.0%, and Hispanic dentists remained stable at 1.5% to 1.8% (X2 = 1.71, p = .19) while Hispanic dental hygienists grew from 1.0% to 2.7%. Notably, compared to White dentists, both Black (OR = 1.56, CI = 1.15-2.17, p = .005) and Asian/ Indian (OR = 2.92, CI = 2.05-4.31, p < .0001) dentists were significantly more likely to work in metropolitan counties. Compared to White dental hygienists, both Black (OR = 2.02, CI = 1.41-3.00, p = .0003) and Asian/Indian (OR = 5.30, CI = 2.40-14.99, p = .0003) dental hygienists were significantly more likely to work in metropolitan counties.

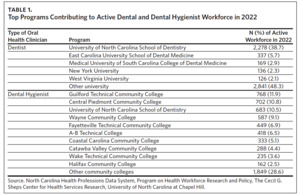

Educational Trends

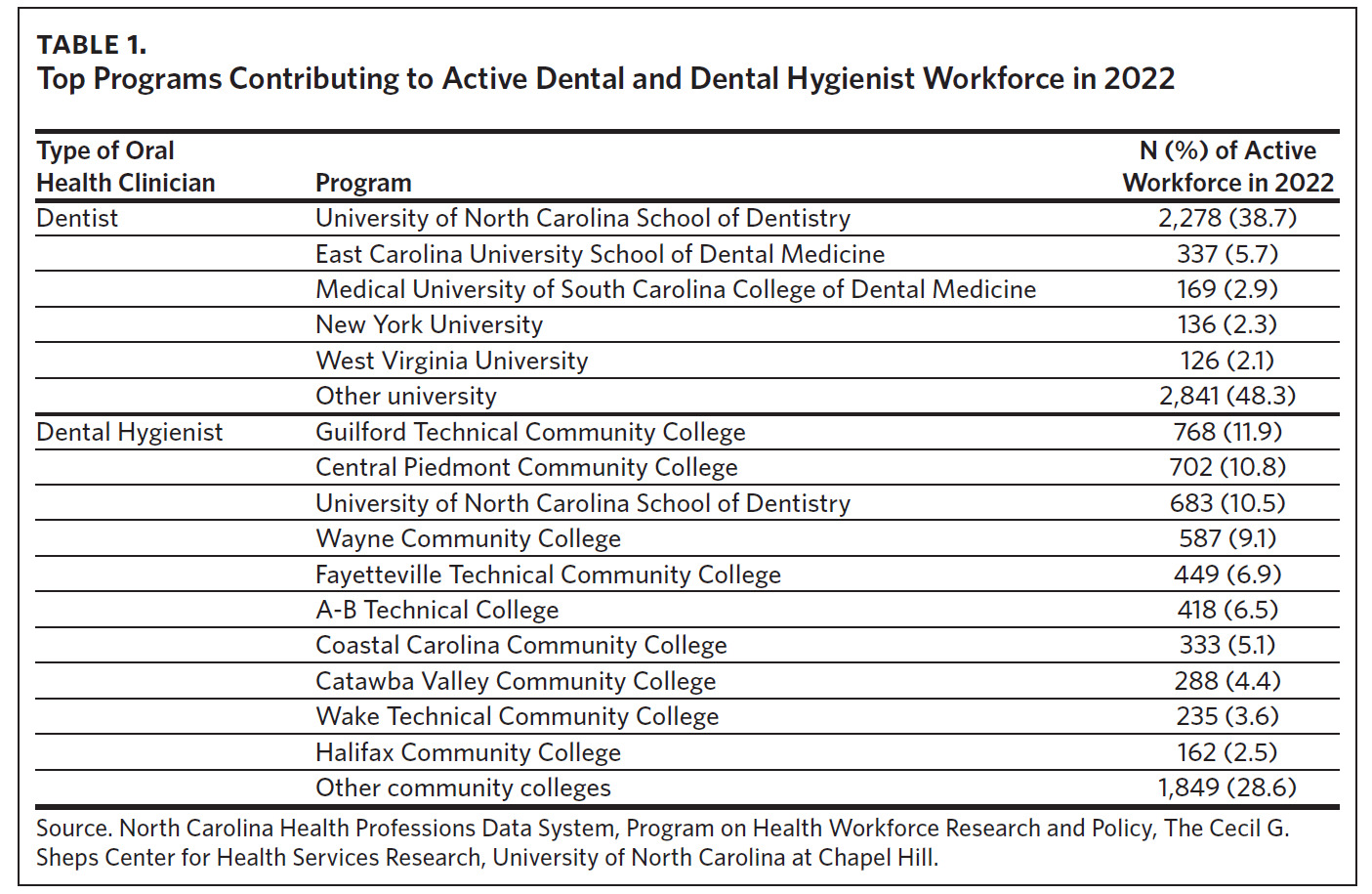

Approximately 44% of all active dentists in North Carolina in 2022 graduated from a dental school located in the state and more than two-thirds of all dental hygienists graduated from a North Carolina dental hygienist program (Table 1). Of the 681 active North Carolina dentists practicing in nonmetropolitan areas in 2022, 46% (n = 313) graduated from the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Dentistry and 8.7% (n = 59) graduated from East Carolina University (ECU) School of Dental Medicine. Compared to out-of-state-educated active dentists in 2022, active dentists who graduated from the UNC School of Dentistry (OR = 1.53, CI = 1.29-1.80) or ECU School of Dental Medicine (OR = 2.03, CI = 1.49-2.74) were significantly more likely to work in a nonmetropolitan North Carolina county.

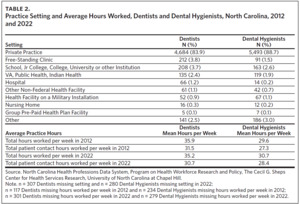

Dentist and Dental Hygienist Practice Settings and Average Hours Worked

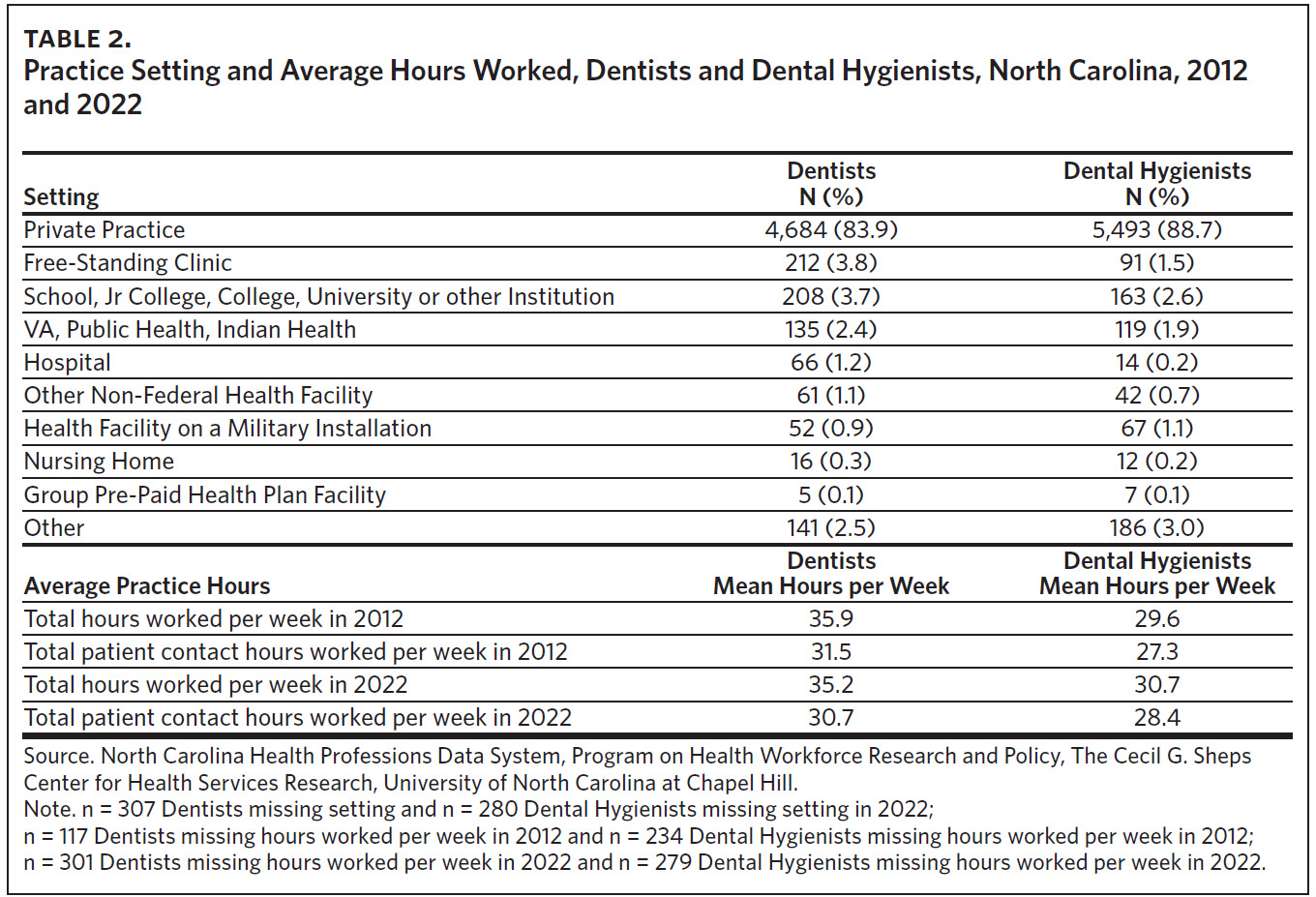

In 2022, the majority of the oral health workforce in North Carolina worked in private practice, including 83.9% of all dentists and 88.7% of all dental hygienists. From 2012 to 2022, the total number of hours worked per week by dentists held steady at 35.9 to 35.2, respectively. Additionally, while not statistically significant, the total number of patient contact hours per week decreased from 31.5 to 30.7. From 2012 to 2022, there were slight but not statistically significant increases among dental hygienists in the total number of hours worked per week, at 29.6 to 30.7, and in the total number of patient contact hours per week at 27.3 to 28.4.

Discussion

North Carolina’s population is growing and is projected to grow 8.5% by 2030, thus becoming the seventh-most populated state in the United States.24 The total number of dentists and dental hygienists in the state increased by 82.5% and 76.5%, respectively, between 2000 and 2022. However, the maldistribution of dentists across the state is increasing—the analysis from this study found from 2000 to 2022 the gap in the ratio of dentists per 10,000 population grew to 3.5 in nonmetropolitan counties compared to 6.0 in metropolitan counties. If current trends in the oral health care workforce continue, existing disparities may be exacerbated as North Carolina’s population grows.

In 2022, almost 50% of dentists in active practice in North Carolina graduated from either the UNC School of Dentistry or ECU School of Dental Medicine. This study found that dentists who graduated from these programs were significantly more likely to work in a nonmetropolitan North Carolina county. The Adams Rural Oral Health and Wellness Scholars (AROWS) program at UNC targets dental students aiming to practice in underserved areas and seeks to improve the distribution of dentists across the state. The dental program at ECU has nine dental clinics located in rural North Carolina counties that provide oral health care in these communities, including community-oriented service and interprofessional models of care.5 Considering the gap in the ratio of dentists to North Carolina population has widened in nonmetropolitan areas, programs such as those at UNC and ECU may be well positioned to expand. Further, with over 75% of active dental hygienists trained in North Carolina, incentivizing rural practice within dental hygienist programs may be a potential solution for improving overall oral health access across the state.

Important changes to North Carolina law have been made to address the lack of access to oral health care in nonmetropolitan counties. For example, Session Law 2021-95 defined the practice of teledentistry, created a mechanism for reimbursement of teledentistry services, and allowed dental hygienists who meet certain criteria to perform dental hygiene care under the direction of a dentist based on a written standing order, within 270 days of the dentist’s standing order, without the physical presence of a dentist.25 These changes to North Carolina law have important implications for those living in rural areas and the aging population, as dental hygienists meeting the stated criteria for providing oral health care based on the standing order are permitted to do so in in federally qualified health centers (FQHC), nursing homes, long-term care facilities, and schools.25 Dental hygienists working in rural areas could help improve access to oral health care given that the gap in the ratio of dental hygienists to North Carolina population is narrowing in rural areas; however, this warrants further investigation over time.

North Carolina’s population is increasing in its racial/ ethnic diversity. As the population grows, so will the overall diversity of the state population. This study found that the demographics of North Carolina’s oral health workforce are disconcordant to the demographics of the state’s population. While Black individuals represented 20.9% of the overall population in 2022, the number of Black dentists only increased from 8.6% to 9.1% from 2012 to 2022. In 2022, only 10% of dentists and only 22% of dental hygienists identified as a racial/ethnic minority. The lack of diversity in the oral health workforce is problematic considering underrepresented minorities have higher rates of oral health disparities than their White counterparts.26 Moreover, racial concordance between health care clinicians and their patients is associated with improved health outcomes.27 In addition to increasing the diversity of the oral health workforce in North Carolina, it is also important to develop a culturally competent workforce by ensuring all clinicians understand the importance of social and cultural influences on their patients’ oral health beliefs and behaviors.28

In 2023, North Carolina became the 40th state to expand Medicaid coverage.29,30 This change may remove some financial barriers that prevent low-income North Carolina residents from receiving oral health services and may help decrease oral health disparities across the state.15 However, increased access to oral health care is reliant on the availability of dentists that accept Medicaid, and only 35.1% of North Carolina dentists reported accepting Medicaid in 2023.15 Additionally, more than 80% of all dentists and dental hygienists reported working in private practice, whereas fewer than 2.5% of all dentists and dental hygienists reported working in public health where Medicaid is likely to be more readily accepted.17 The literature has consistently demonstrated that increasing the reimbursement rates increases participation in Medicaid.31

Findings from this study have important implications for policymakers and align with several recommendations from the National Conference of State Legislatures32 and the NCIOM Oral Health Transformation Task Force report, Transforming Oral Health Care in North Carolina.17 Examples include supporting dental schools to expand rural-focused training programs, diversifying the oral health workforce, balancing payment mechanisms (especially with respect to dental insurance under the Medicaid program), and linking existing data with Medicaid data and patient outcomes.

Limitations

While this use of licensure data allowed for an important update on the oral health workforce in North Carolina, the study has several limitations. The analysis is based on self-reported data from licensure application and renewal forms. Information regarding which dentists participate in Medicaid is not captured within licensure data. Additionally, North Carolina population data categorize Hispanic ethnicity separate from race, while dentist and dental hygienist licensure applications include an option to identify as Hispanic ethnicity within the racial category options (e.g., Black, Asian). However, applicants may not choose more than one racial category option, and so, by North Carolina population data standards per OSBM, these responses would be categorized as “other.” Additionally, the race variable in the licensure data includes the option Asian/Indian, which does not specify whether Indian refers to Native American/Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, or being from Asia/India. These differences in race/ethnicity categorization limited the possible comparisons between the North Carolina population and North Carolina oral health clinicians.

Conclusion

North Carolina continues to work to improve access to oral health care for its residents, demonstrated by recent statutory changes25,30 and the 2024 NCIOM Oral Health Transformation Task Force recommendations.17 This study supports the need for remaining work to increase access to oral health care in North Carolina’s most underresourced communities, including balancing payment mechanisms, improved data collection, enhancing community-based training, and integration of oral health services within overall whole-person health care services.