Background

The landmark National Institutes of Health report, “Oral Health in America,” summarizes the value of school-based oral health programs (SBOHP) to the thin network of safety-net providers.1 SBOHP are lauded in the report as an effective approach to population-based care and a stalwart of public health, especially in rural and underserved communities, where geographic or financial access to services is limited2 and utilization patterns are disparate.3

SBOHP are needed in states like North and South Carolina, despite continuing efforts to bridge the access-to-care gap that have resulted in the growth of availability of dental care for vulnerable children in the private practice sector. Between 2017 and 2021, 586 dentists entered practice in North Carolina; the majority (60%) went into the five counties where populations make up 31% of the state’s citizenry.4 This is in stark comparison to the 20% of dentists new to the state going into 90 counties that represented 61% of the state’s mostly rural population.4 Accessibility is further confounded for patients with public insurance. The oral health access gaps in both North and South Carolina are largely attributed to lower rates of dentists’ participation in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP),5 a profound issue given approximately 40% and 44% of children are enrolled in North and South Carolina Medicaid programs, respectively.5

It is estimated that 34 million hours of lost time in schools nationally is attributed to unmet oral health needs.5 SBOHP have emerged as an essential component of the dental safety net to ensure children do not have to miss school or suffer from untreated dental disease. In 2018, The Duke Endowment and the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, and later the Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina Foundation, partnered on a new six-year grant initiative to support the development and expansion of comprehensive SBOHP in rural, underserved areas of North and South Carolina. Academic partners from the Colleges of Dental Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and East Carolina University (ECU) were enlisted to develop the grant program, including the analytics to measure its success. National SBOHP thought leaders aided in the design and helped to establish expectations for grantee performance and child oral health outcomes. Sustainable, evidence-based clinical plans, modeled after other federally supported initiatives, were emphasized.6 The work, which included a robust technical assistance curriculum and toolkit, has previously been presented, along with the framework and guiding principles used in the grant program’s development.7

This initiative has brought services to children who otherwise would not have received care. As the 2024–2025 school year began, the initiative had SBOHP in 64 counties (Figure 1) through 43 grantee organizations, most of which are federally qualified health centers (n = 20), health departments (n = 15), universities or colleges (n = 5), and other nonprofit organizations (n = 3). A comprehensive evaluation of the initiative is scheduled for 2025, though preliminary data (as of January 2022) demonstrate the following impacts:

-

279 schools have been reached

-

15,795 children have received services

-

6,598 children have received dental sealants

-

85,834 prevention services have been provided

-

9,955 treatment services have been provided.

These metrics were achieved despite the challenges presented during the COVID-19 pandemic, which were significant at the end of the 2020 school year and into the 2022 school year. As with other similar school programs, disruptions included suspension of programs for on-campus care delivery, dental team attrition, and disconnection from patients.8 As schools reopened, preference was given to SBOHP with mobile units, or RV-style operatories. Many of the grantee organizations use portable equipment set up inside the schools. Out of an abundance of concern over potential spread of COVID-19, programs that only used portable equipment had greater difficulties and delays with reentering their schools. The long-term effects of COVID-19 on the SBOHP have been similar to those faced by traditional dental practices: higher than inflationary costs of doing business and challenges with workforce recruitment and retention.9

During the height of the pandemic, the initiative’s fate and timing were questioned by many of its chief supporters, including some grantees. It was anticipated that the gains in children’s oral health would regress during the pandemic due to separation from care in all settings, not just schools. Rather than terminating the grant, leadership made the decision to continue the initiative, anticipating elevated levels of disease upon return to school. Those predictions were proven to be correct, with children having less utilization and worse clinical presentations after 2020 compared to 2019.10 While the needs of children were anticipated, the operational needs of the SBOHP were less clear. Anecdotally, it seemed the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the workforce and partnerships of the grantee organizations. As such, an assessment of each program’s capacities and abilities to fulfill their grants was warranted.

Methods

In 2023, the SBOHP appeared to be transitioning to a new post-COVID-19 normalcy, but it was unclear how the technical assistance curriculum was impacted by the clinical, social, and financial impacts of the pandemic. It was a fortuitous time to conduct a process evaluation of the SBOHP. As a part of continuous quality improvement, the leadership team sought to conduct a post-COVID-19 SWOT (Strengths-Weaknesses-Outcomes-Threats) analysis [14] to determine if adjustments or enhancements to the SBOHP initiative were warranted.

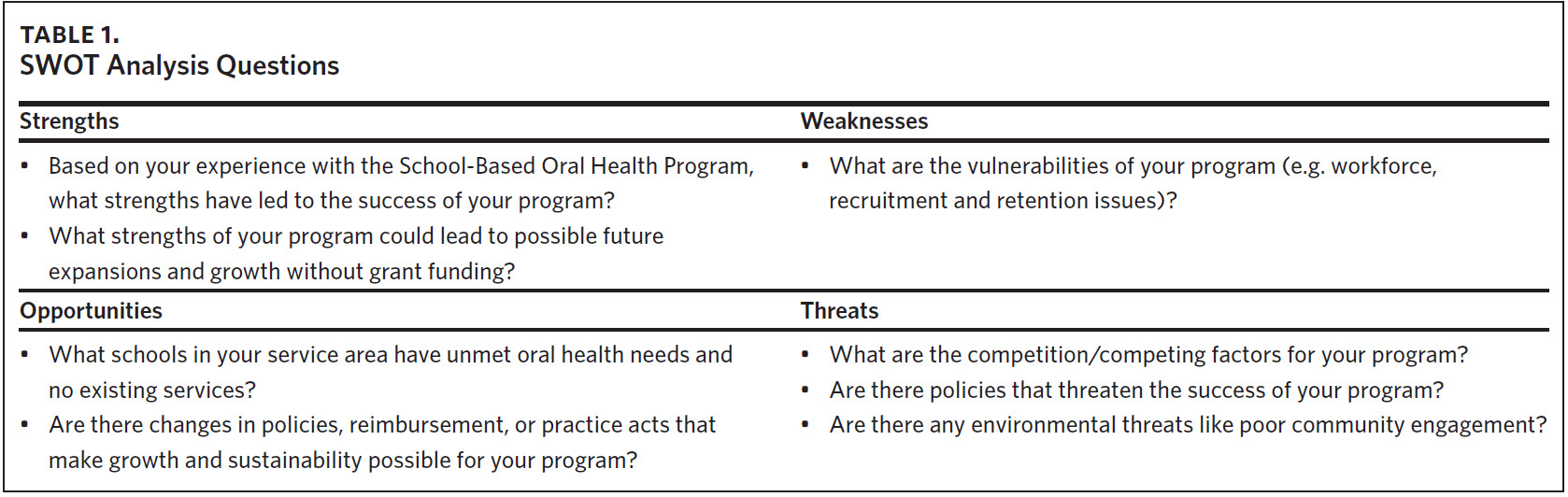

As a part of the 2022 SBOHP annual conference for the grantee organizations (n = 34), members completed a SWOT analysis as a team in facilitated tabletop discussions. The table facilitator introduced the SWOT questions that were published on a worksheet and guided participants through each section. After a timed discussion for each section (approximately 20 minutes), participants were asked to complete one worksheet per organization. The questions are delineated in Table 1.

A phenomenology approach11 was used to analyze the data collected through the SWOT questionnaire, which consisted of entirely open-ended, qualitative responses. Phenomenology is a qualitative research methodology that permits the assessment of a study participant’s experiences from their unique perspective. It is frequently used in health services research to contextualize quantitative data. The SWOT analysis data were analyzed using content analysis and descriptive analysis techniques. To control for bias, two levels of analyses were conducted. In total, three coders were involved in the content and descriptive analyses.

Individual grantee organizations were coded by organizational type to determine if there were trends based on the type of organization. After stratifying responses by organization type, it was determined that no statistical analyses would be conducted due to the small numbers of responses. Only the five most frequent themes for each SWOT domain are presented.

Results

Thirty-three of the 34 grantee organizations completed the SWOT analysis questionnaire. Table 2 summarizes the top five most frequent themes for each SWOT domain. Programs most frequently identified having the right team members and productive relationships with schools as strengths. These strengths were countered by most programs (60.6%) reporting workforce recruitment and retention as their primary weakness. The most frequently recorded opportunity for improvement was the need for

Medicaid reimbursement. Several respondents provided context that reimbursement, sustainability, and compensation models for their teams were inextricably linked. The primary threat to program success was reported as lack of engagement by schools or parents.

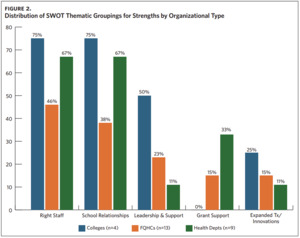

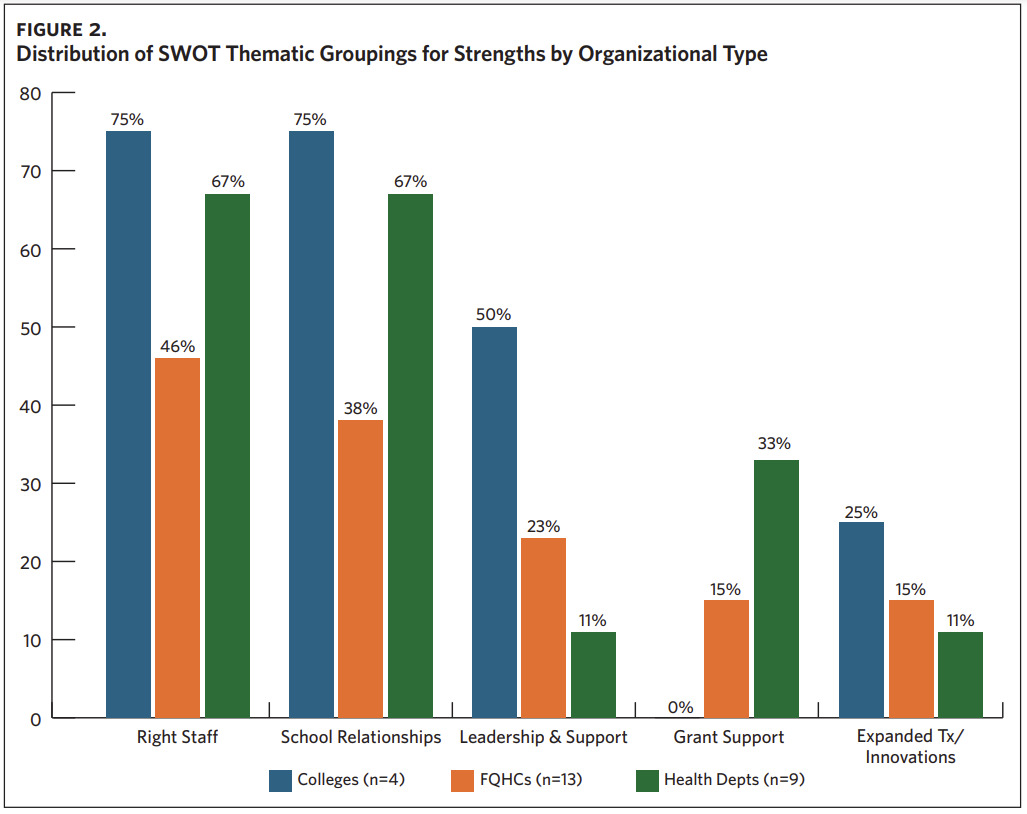

Figure 2 delineates the differences in rates of response about strengths by organization type. Workforce issues were the most prevalent weakness identified by federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and health departments, whereas “leadership or bureaucracy” was an exclusive issue for the colleges that participated in the program (Figure 3). This disruption aligns with what would be intuitively expected, given that colleges are large organizations with complex layers of management and the model is designed (and its desired outcomes are likely in better alignment with) community-based organizations. The workforce issues identified by FQHCs reflect what we understand from national trends.12 The health departments in this project are county-run, not a part of large centralized public agencies, so it is expected they would trend similarly with FQHCs.

Related to the other SWOT domains, the identified threats appear to be of most concern to FQHCs, especially the issue of reimbursement (Figure 4).

As a part of the opportunities section of the SWOT analysis, respondents were asked to reflect on changes to policy issues that might address the weaknesses and threats. Two thematic areas emerged from the data: Medicaid reimbursement and changes to each state’s hygiene practice statute. Nearly 40% of the participants were in agreement that reevaluating Medicaid reimbursement warrants the attention of policymakers. Approximately half the college and FQHC respondents (50% and 54%, respectively), though only 22% of health departments, identified Medicaid reimbursement changes as a much-needed opportunity. Anecdotally, a few respondents gave specific feedback:

-

Medicaid rates have not changed in many years (except for temporary increases during COVID-19.

-

There is a need for reimbursement for assessments and teledentistry.

-

There is a need for reimbursement incentives for silver diamine fluoride (SDF) and silver modified atraumatic restorative technique (SMART).

-

A code should be created for reimbursement of school-based visits, similar to D9410 (extended care facility code).

Similarly, respondents provided specific suggestions regarding opportunities for potential modifications to the states’ Board of Dentistry rules on hygiene practice statute changes. A few examples include:

-

Authorizing hygienists working under public health authorities to oversee more than one dental assistant would reduce costs of delivering care in school settings.

-

Use hygienists in providing SMART restorations.

-

Authorize the use of dental therapists in community health centers.

Discussion

The good news is that the school-based oral health initiative in the Carolinas emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic poised for successful implementation. The challenging news is that one in five North Carolina kindergarten students has untreated tooth decay in the post-COVID-19 era.13 How do we leverage the school-based oral health program expansions and investments to improve the epidemiology of children’s oral health?

Medicaid Reimbursement

The SBOHP in the current study have communicated that Medicaid reimbursement rate increases should be a priority. North Carolina expanded its Medicaid program in 202314; growing enrollments will increase dental expenditures for the program, making it difficult to increase reimbursement rates without considerable state investment.

Operating Room Crisis

Organized pediatric dentistry and pediatric medicine face a new crisis in the wake of COVID-19 in diminishing availability of operating rooms.15,16 This crisis is especially stressful in the rural safety net, where rates of disease are the highest. Children with especially severe decay are often treated surgically under general anesthesia to minimize the pain of treatment and arrest disease trajectory with fewer interventions. Due to reimbursement, surging demands for surgical interventions, and other health system factors, hospitals are reducing availability of operating rooms for dental procedures. This presents a unique opportunity for both medical and dental providers to work with SBOHP to address decay at the population level.

The Role of Primary Care

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently made a call to action for pediatricians to be engaged with school-based oral health programs by working with school nurses to facilitate access to care, advocating for evidence-based school oral health programs in their communities, and more.17

School nurses are the frontline health care professionals in public schools.18 As SBOHP seek to strengthen their relationships and elevate engagement with schools, cultivating partnerships with school nurses should be a priority.

Promote Cost Savings, Evidence-based Care

The SWOT analysis linked workforce recruitment and retention with compensation and reimbursement. While Medicaid reimbursement rates might not be within the sphere of SBOHP influence, the care they provide is. A few of our respondents specifically mentioned the use of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) as an example of an evidence-based care innovation that has the bonus of being a cost-effective therapy for both programs and the families they serve.19 Both the clinical- and cost-effectiveness of SDF, compared to traditional caries management therapies, are well documented, with one study showing annual savings of nearly $300 per child.20 Applying this cost savings to populations served by SBOHP adds up for both programs and payors such as Medicaid.

Teledentistry is another cost-effective approach for improving access and care outcomes in school-based programs that has not yet been fully optimized in our SBOHP.

Other states are demonstrating the effectiveness of equipping dental hygienists with teledentistry technologies in school-based settings to screen and assess students’ oral health status.21

Workforce Enhancements

One of the unanticipated policy developments during the implementation of the Carolinas’ SBOHP was North Carolina Senate Bill 146, which allowed public health dental hygienists to provide limited preventive services without direct supervision by a dentist. The passage of the bill was a collective effort led by the North Carolina Oral Health Collaborative. It was informed by lessons learned from South Carolina’s hygiene practice act that allowed grantees from that state to operate with greater efficiencies than their North Carolina peers in the early days of the initiative.

Next Steps

The original partners for the SBOHP in the Carolinas will transition from an ‘initiative’ (a time-limited program) to an ‘institute’ (a sustainable and expanding resource of knowledge, expertise, and research) in 2025. These plans are in alignment with Recommendation 13 from the North Carolina Institute of Medicine Oral Health Transformation Task Force’s report, Transforming Oral Health Care in North Carolina.22 Our vision for the School-Based Oral Health Institute is to address rural and underserved children’s oral health inequities through comprehensive technical assistance, advocacy, and analytical support. In addition to continuing the original scope of work, priorities include: a) continuing (and updating) the established technical assistance curriculum; b) supporting the continued expansion of our existing programs, or new programs that did not benefit from the original funding; c) building a team of peer coaches, who will be school-based experts from our grantee organizations; d) providing new funding for existing grantees to address early childhood caries in Head Start programs; e) continuing to cultivate the network of grantee organizations that remain calibrated for adoption of new care innovations in oral health and other care-related opportunities; and f) contributing to the national philanthropy community by availing the institute’s services and resources to foundations in other states with priority for partners in the National Rural Health Association and Grantmakers In Health’s (GIH) Public Private Partnership initiative.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the SBOHP was made possible by The Duke Endowment (a major funder of the North Carolina Medical Journal) and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundations of both North and South Carolina.

The team wishes to acknowledge one of the original thought leaders and influencers of our program design, Dr. Mark Doherty. We thank him posthumously for his visionary commitment to the design of the initiative.