Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) individuals make up at least 7.1% of the US population.1 LGBTQ+ populations throughout the United States face identity-related discrimination and stigma at the intrapersonal (i.e., individual response to discrimination), interpersonal (i.e., interactions between stigmatized and non-stigmatized individuals), and structural (i.e., labeling, stereotyping, and discrimination in a context of power differentials) levels.2,3 However, LGBTQ+ identity-related discrimination and stigma are not uniform across the United States; LGBTQ+ individuals experience more discrimination and stigma in certain portions of the country, including states in the South such as North Carolina.4

Due to anti-LGBTQ+ stigma and discrimination, LGBTQ+ populations experience worse physical, mental, social, and financial health in comparison to their cisgender and heterosexual counterparts, both within and outside of the cancer context.5–11 LGBTQ+ populations are also more likely to engage in coping behaviors with negative health consequences, such as binge drinking and cigarette smoking.12,13 Such maladaptive coping behaviors and resultant disparities are frequently contextualized in the minority stress model (i.e., the stress caused by discrimination and stigma) as well as the National Institutes of Health’s Sexual and Gender Minority Health Disparities Research Framework (i.e., a socioecological approach to drivers of health disparities).14–17 The cumulative impact of anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination and stigma experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals contributes to high rates of life-threatening experiences and outcomes, such as violence, substance use, poor mental health, experiences of homelessness, and suicide.

At the same time, some cancer survivors experience increased rates of similarly life-threatening outcomes, such as substance use and suicidality.18,19 Therefore, we hypothesize that the combined effects of anti-LGBTQ+ stigma and discrimination and cancer will result in LGBTQ+ cancer survivors reporting higher rates of discrimination, violence, poor mental health, substance use, and accidental overdose outcomes in comparison to LGBTQ+ individuals without a cancer history. However, the experiences of such life-threatening outcomes among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in an area of the United States with substantial anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination and stigma4 have not been previously described in the literature. Thus, using data from the North Carolina LGBTQ+ Health Needs Assessment, we aimed to investigate potential differences in discrimination, violence, mental health, substance use, and accidental overdose outcomes among LGBTQ+ individuals with and without a cancer history. Further, we aimed to describe commonly reported mental health coping behaviors and barriers to mental health services among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors. Findings specific to LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in North Carolina are of the utmost importance for identifying where health services and programs could be improved to minimize life-threatening outcomes and move toward health equity for this population.

Methods

The North Carolina LGBTQ+ Health Needs Assessment

Data were collected by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) through its 2023 North Carolina LGBTQ+ Health Needs Assessment. The LGBTQ+ needs assessment survey was a cross-sectional instrument that included questions about demographics and identity, physical and mental health, health care access, substance use, discrimination, violence, homelessness, and other social determinants of health. Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age, currently living in North Carolina, and identified as LGBTQ+. Participants were recruited at 27 LGBTQ+ Pride events across the state between June 2023 and October 2023 (Figure 1). At each Pride event, the North Carolina LGBTQ+ Health Needs Assessment had a booth or table from which NCDHHS staff (J.W.) and volunteers physically approached LGBTQ+ individuals to participate in the needs assessment. The needs assessment was completed on a tablet at each Pride event. While most LGBTQ+ Pride events happen in the month of June (i.e., Pride Month), celebrations at the city or county level often take place throughout the summer and into the fall. LGBTQ+ Pride events are celebrations, often festivals or parades, of LGBTQ+ identity and culture that strive to provide all LGBTQ+ individuals a safe space to be their authentic selves. A total of N = 3170 LGBTQ+ individuals engaged in the informed consent process and took part in the needs assessment. Those who took part in the needs assessment were provided an LGBTQ+ Pride pin as a thank you for their time. The North Carolina LGBTQ+ Needs Assessment was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. Survey questions for each outcome can be found in the Appendix.

Cancer and Demographic Factors

The presence of a cancer history was identified in this analysis using a single question, which asked participants if they have had a cancer diagnosis. Other demographic characteristics used in this analysis included gender, age at survey (continuous), race and ethnicity, education level, annual household income, primary source of health insurance coverage, and self-reported rurality. Due to small group sizes, gender was collapsed into four categories: cisgender woman, cisgender man, non-binary/genderqueer, and transgender/multiple gender/another gender. Race and ethnicity were collapsed into four categories: White, Black, Hispanic/Latine/Latinx, and Multi-racial/another race. Education was collapsed into four categories: high school or less, some college, associate or bachelor’s degree, and graduate degree.

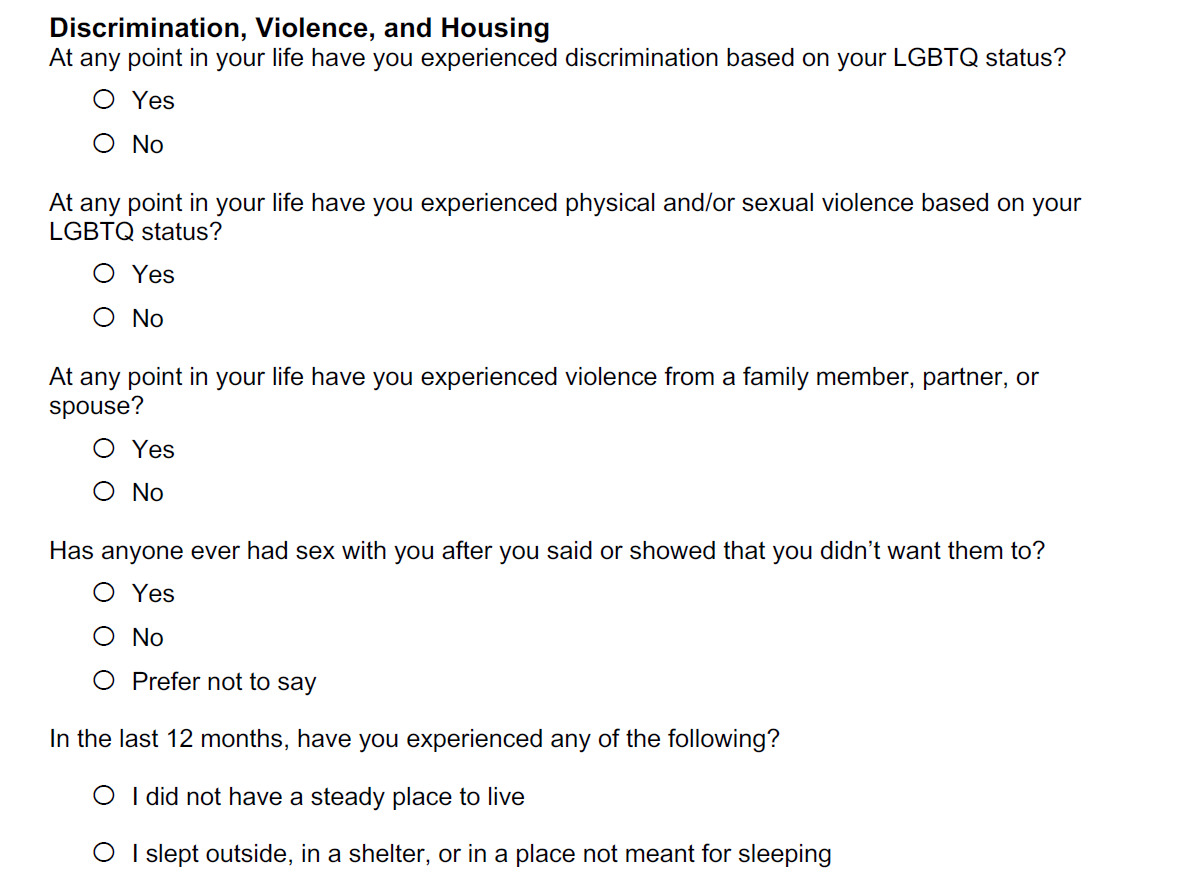

LGBTQ+ Discrimination, Violence, and Experiences of Homelessness

LGBTQ+ participants were asked if they had ever experienced: discrimination based on their LGBTQ+ identity (i.e., LGBTQ+ discrimination); physical or sexual violence based on LGBTQ+ identity (i.e., LGBTQ+ violence); violence from their spouse, partner, or family member (i.e., spouse or family violence); or anyone having had sex with them after they said no or showed that they did not want them to (i.e., sexual assault). Experiences of homelessness were ascertained by asking participants two questions: 1) if they, in the last 12 months, did not have a consistent place to live, and 2) if they slept outside, in a shelter, or in another place not meant for sleeping. Participants were considered to have experienced homelessness if they selected yes to either question.

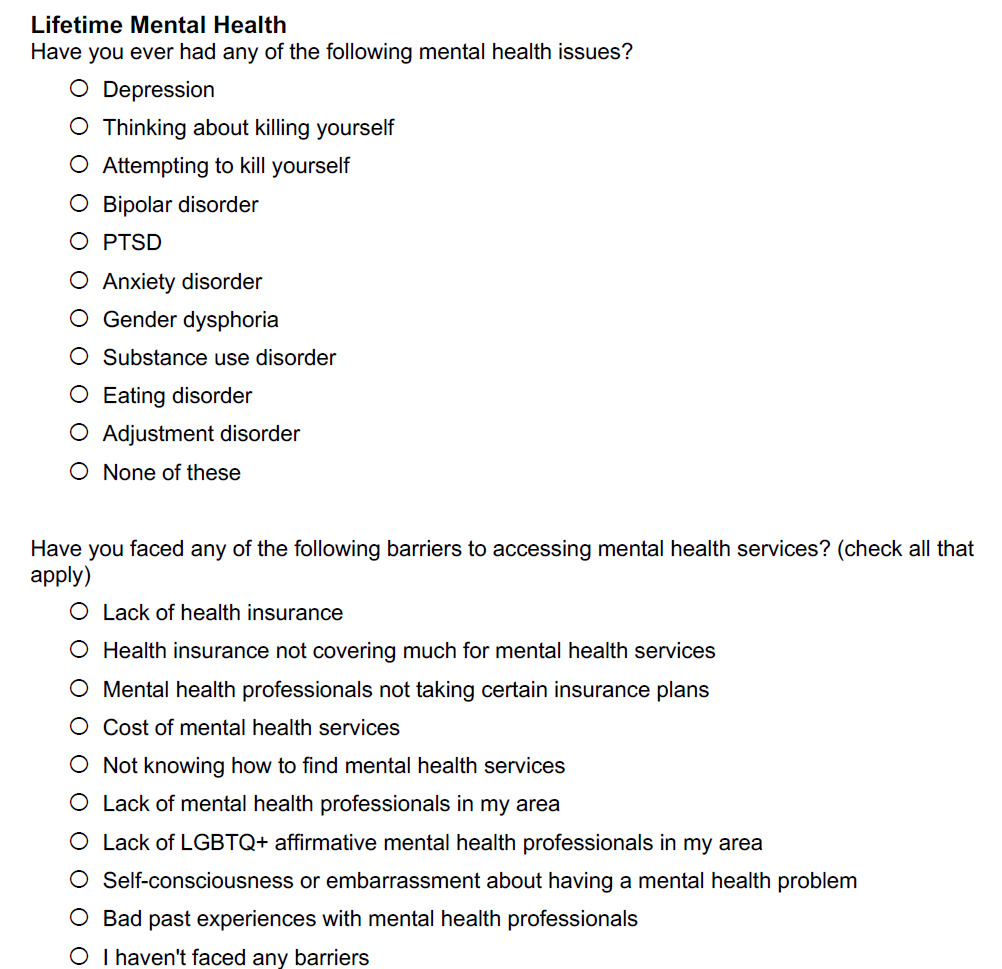

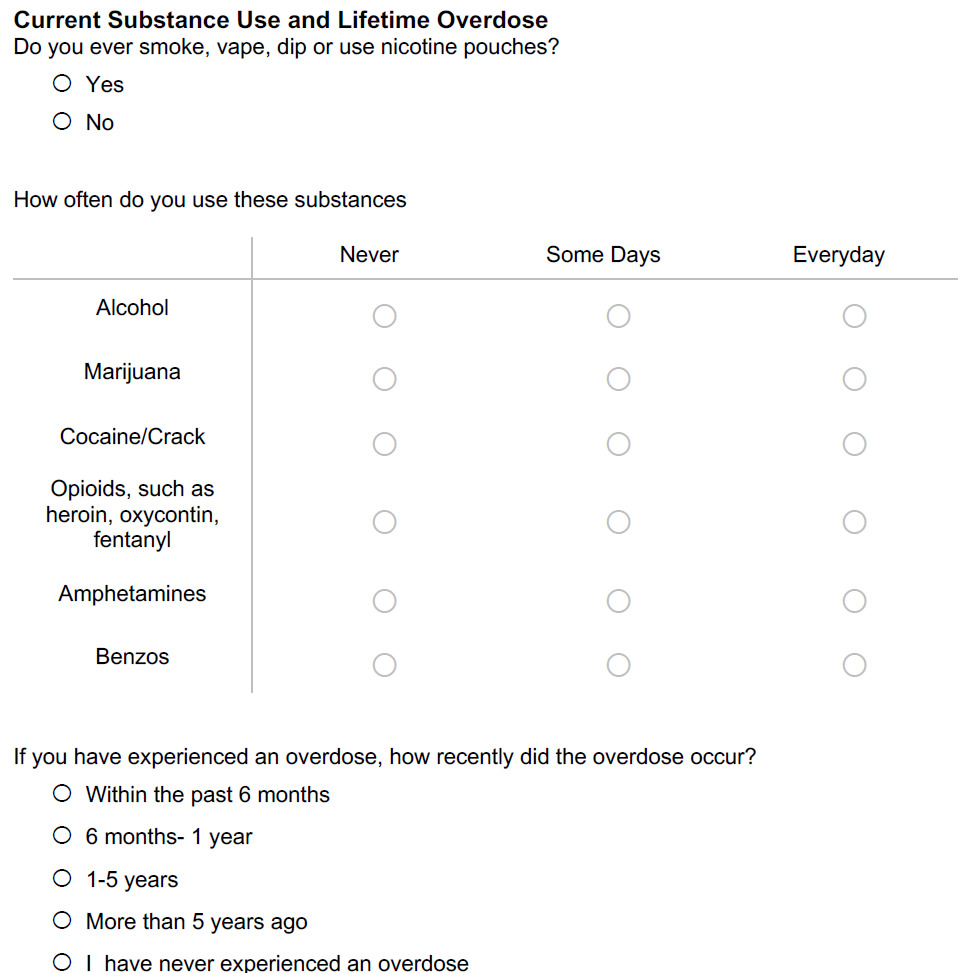

Mental Health, Substance Use, and Accidental Overdose

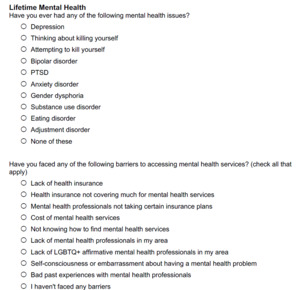

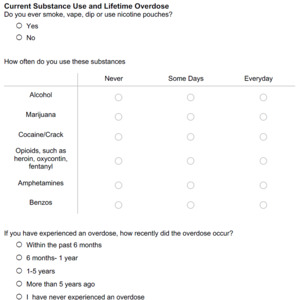

Mental health was ascertained by asking a single ‘select all that apply’ question that asked if participants had ever had any of the following mental health issues: depression, thinking about killing yourself, attempting to kill yourself, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, and anxiety disorder. Substance use questions asked about the frequency of current use (never, some days, every day) of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, opioids, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines. Nicotine product use was ascertained by one question asking if participants use nicotine products, followed by a list of nicotine products, including cigarettes, vapes, chewing tobacco, and other nicotine products. Dichotomous substance use outcome variables were generated by collapsing some days and every day, resulting in use versus no use for each substance. Participants classified as reporting hard drug use if they reported using cocaine, opioids, amphetamines, or benzodiazepines. Accidental overdose was ascertained by asking if the participant had ever accidentally overdosed and when it occurred. The binary outcome of accidental overdose was categorized as any report of accidental overdose versus never having had an accidental overdose.

Mental Health Coping Strategies and Barriers to Mental Health Services

Mental health coping strategies were measured by asking a ‘select all that apply’ question about if participants had used any of the following for their mental health: therapy or counseling; support group; prescription medication; meditation; talking with friends or family; exercise or outdoor activities; alcohol, tobacco, or drugs; or none of these. Barriers to mental health services were measured with a ‘select all that apply’ question about which barriers participants have ever faced to accessing mental health services, including: lack of health insurance, health insurance not covering much, mental health professionals not taking certain insurance plans, cost of mental health services, not knowing how to find mental health services, lack of professionals in area, lack of LGBTQ+-affirmative professionals in area, embarrassment about a mental health problem, bad previous experience, or no barriers. Related barriers were collapsed, resulting in seven types of barriers: cost, insurance, LGBTQ+-affirmative provider availability, general availability, bad prior experiences, unsure how to find, and mental health stigma.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in demographic groups between LGBTQ+ participants that reported a prior cancer diagnosis (i.e., cancer survivors) and those who did not were assessed using Chi-squared tests. Differences in all outcomes (i.e., LGBTQ+ discrimination, violence, homelessness, mental health, substance use, and overdose) by cancer status were assessed using Chi-squared tests. Differences in outcomes by cancer history were visualized in bar charts. Multivariable logit models controlling for demographic characteristics that differed by cancer status were used to generate predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for LGBTQ+ individuals with and without a cancer history for each outcome. Multivariable logit models were also used to estimate average marginal effects (AME) and 95% CI for each outcome. Logit models controlled for sexual orientation, gender, age, race and ethnicity, education, income, and rurality. Lastly, mental health coping strategies and barriers to mental health services among LGBTQ+ individuals with a history of cancer were visualized using bar charts.

Results

A total of N = 200 (6.3%) of the N = 3170 LGBTQ+ participants reported ever being diagnosed with cancer (Table 1). LGBTQ+ cancer survivors differed from those without a cancer history across most demographic characteristics except for race and ethnicity. LGBTQ+ cancer survivors identified as gay or lesbian (45.5% versus 34.7%) and cisgender (cis-woman: 60.9%, cis-man: 22.3% versus cis-woman: 45.0%, cis-man: 20.1%) more frequently than LGBTQ+ participants without a cancer history. LGBTQ+ cancer survivors were also older at the time of the survey (ages 40–64, 47.2% versus 15.5%), more educated (graduate degree, 27.9% versus 16.0%), higher income (> $100,000, 24.4% versus 17.0%) and more frequently on public insurance (18.0% versus 10.3%). There was no difference in uninsurance between LGBTQ+ individuals with and without a cancer history (8.2% versus 7.5%).

In bivariate analyses, LGBTQ+ cancer survivors were more likely to report ever experiencing LGBTQ+ violence (33.0% versus 23.3%, P = .002), spouse or family violence (50.5% versus 38.2%, P = .001), and sexual assault (48.5% versus 39.2%, P = .021), as well as experiencing homelessness in the last 12 months (17.0% versus 5.8%, P < .0001; Table 2). No difference in lifetime experience of LGBTQ+ discrimination was detected by cancer status. LGBTQ+ individuals without a cancer history were more likely to report depression (72.7% versus 63.5%, P = .005), anxiety (64.0% versus 51.1%, P < .0001), and suicide ideation (42.4% versus 29.0%, P < .0001). No difference was detected for PTSD, bipolar disorder, or suicide attempt. At the same time, LGBTQ+ cancer survivors were more likely to report current cocaine use (9.0% versus 2.0%, P < .0001), opioid use (8.5% versus 1.8%, P < .0001), amphetamine use (8.5% versus 5.2%, P = .047), benzodiazepine use (11.0% versus 3.0%, P < .0001; Table 2), and accidental overdose (24.0% versus 7.0%, P < .0001; Figure 1). However, no difference was observed regarding alcohol, marijuana, or nicotine product use.

Using multivariable logit models, cancer history was associated with an 8.1 to 19.1 percentage point increase in the probability of all discrimination, violence, and homelessness outcomes. Among LGBTQ+ individuals in North Carolina, a cancer history was associated with an 8.1 (95% CI: 1.6, 14.5) percentage point increase in LGBTQ+ discrimination, a 15.1 (95% CI: 7.8, 22.5) percentage point increase in LGBTQ+ violence, a 16.7 (95% CI: 9.1, 24.1) percentage point increase in spouse or family violence, a 14.1 (95% CI: 6.0, 22.2) percentage point increase in sexual assault, and a 19.1 (95% CI: 11.6, 26.6; Table 3) percentage point increase in experiencing homelessness.

When assessing mental health outcomes, a history of cancer only had a significant association with reporting PTSD (AME: 8.9, 95% CI: 1.8, 16.0) among LGBTQ+ individuals in North Carolina. No other significant differences in mental health (i.e., depression, anxiety, bipolar, suicide ideation, suicide attempt) were observed between LGBTQ+ individuals with and without a cancer history. Further, using multivariable logit models, a prior cancer history did not influence marijuana use among LGBTQ+ individuals. A cancer history was associated with an 8.8 percentage point lower probability (95% CI: –16.0, –1.6) of reporting alcohol use. However, when assessing other substance use outcomes, a prior cancer history was associated with a 9.0 (95% CI: 1.6, 16.5) percentage point increase in nicotine product use, a 8.9 (95% CI: 3.8, 14.1) percentage point increase in use of cocaine, a 7.4 (95% CI: 2.9, 11.8) percentage point increase in use of opioids, a 6.0 (95% CI: 0.9, 11.0) percentage point increase in use of amphetamines, a 7.8 (95% CI: 3.0, 12.5) percentage point increase in use of benzodiazepines, and a 22.5 (95% CI: 15.2, 29.8) percentage point increase of accidental overdose.

When assessing the mental health coping strategies used by LGBTQ+ individuals with a history of cancer in this sample, the most common types of coping were talking with family and friends (46.5%), therapy or counseling (40.0%), use of prescription medications (40.0%), and exercise or outdoor activities (39.5%; Figure 2). However, notably, 21.0% of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors reported using alcohol, tobacco, or drugs to cope. Further, the most common barriers to mental health services among LGBTQ+ individuals with a history of cancer included cost barriers (36.0%), insurance barriers (33.5%), and barriers related to the unavailability of LGBTQ+-specific mental health services/trained professionals (21.5%; Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, having had cancer was associated with a substantial percentage point increase in all discrimination and violence outcomes, as well as the use of most substances. At the same time, 1 in 5 LGBTQ+ cancer survivors reported using alcohol, tobacco, or drugs to cope with their mental health. The most frequently reported barriers to accessing mental health services were cost and insurance. While LGBTQ+ cancer survivors may not report mental health challenges more frequently than LGBTQ+ individuals without a cancer history, the increased probability of discrimination and violence may impact the severity of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors’ existing mental health challenges. The impact of discrimination and violence on the severity of mental health outcomes may result in the increased experiences of homelessness, suicide attempts, substance use, and accidental overdose among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in North Carolina. While LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in unadjusted analyses are less likely to report mental health challenges, no differences are observed in adjusted models, likely because age is a major driver of poor mental health in LGBTQ+ populations.20

Over two-thirds of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in this study reported discrimination, and one-half reported violence victimization (i.e., LGBTQ+ violence, spouse or family violence, and sexual assault). While, to our knowledge, no literature has assessed these outcomes among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors specifically, the proportion of LGBTQ+ individuals reporting discrimination and violence is consistent and at times exceeds what is reported in the literature among LGBTQ+ populations in general.21,22 Finding higher rates of domestic violence among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in comparison to LGBTQ+ individuals without a history of cancer is also consistent with the literature; a recent meta-analysis has linked cancer diagnosis with violence.23 These findings in context suggest that LGBTQ+ cancer survivors experience unique risk factors for discrimination and violence that stem from both LGBTQ+ identity and the social and environmental contexts in which cancer and violence are more common.

In this study, LGBTQ+ cancer survivors were more likely to report PTSD, homelessness, the use of a variety of substances, and accidental overdose than LGBTQ+ individuals without a cancer history. LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in this study reported homelessness in the last 12 months at over double the proportion of those without a history of cancer. The proportion of LGBTQ+ individuals without a history of cancer reporting recent homelessness in this study is consistent with the literature.24 The proportion of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors reporting prior suicide ideation or attempts is consistent with the literature among LGBTQ+ populations, while having ever accidentally overdosed was substantially higher than what is reported in the literature for cancer survivors and the general population.19,25,26 Furthermore, the findings and the literature align in demonstrating that cancer survivors experience an increased use of substances, including illicit drugs.18 These findings contextualized together suggest that the trauma of a cancer diagnosis in addition to the trauma resulting from discrimination and violence may have serious and life-threatening impacts on LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in North Carolina.

The findings of this survey point to two primary recommendations. First, we recommend improving access to affordable and LGBTQ+-friendly mental health services. Importantly, the proportion of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors who reported suicide ideation was nearly seven times the prevalence of thoughts of suicide among North Carolinians in 2021.27 In the context of the uninsurance rate of this sample (7.5%), our finding that insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs being the most common barriers to mental health services suggests that the coverage LGBTQ+ cancer survivors do have is inadequate to access appropriate care. While psychosocial interventions have been observed to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety among LGBTQ+ individuals, structural changes are needed to guarantee access to mental health services for LGBTQ+ cancer survivors.28 Prior research has demonstrated that policy changes such as payment parity for telehealth services, authorization of audio-only services, and the ability to provide services across state lines increased access to virtual mental health services during COVID-19.29 However, a majority of individuals in the United States still face substantial barriers to accessing mental health services.30 Research revolving around multi-level strategies to expand access to mental health services for LGBTQ+ cancer survivors is of the utmost importance in the context of the findings of this study. However, even if access is systematically expanded for LGBTQ+ cancer survivors, the availability of LGBTQ+-specific services may also be lacking.31

Cancer centers, specifically in states that have high levels of anti-LGBTQ+ stigma like North Carolina, would benefit from accelerating the development and adoption of LGBTQ+ equity programming or the delivery of bundled interventions and services specific to the LGBTQ+ population. Our findings, combined with emergent literature, underscore the urgent need for cancer centers to cultivate a culture of safety and combat discrimination, violence, and minority stress among LGBTQ+ cancer populations.32 Our findings align with the literature and suggest that caring for LGBTQ+ survivors should center on principles of trauma-informed care.33 Our findings and the larger body of literature suggest that increased financial assistance for such programming is another critical component of increasing access to care.11,34,35 Further, our findings and literature that has identified a need for substance use interventions for LGBTQ+ cancer survivors both suggest that healthy coping and harm reduction strategies may be particularly important to consider in the development of LGBTQ+ equity programming within cancer centers.36

This study has several limitations. First, the use of data from a secondary needs assessment comes with limitations to generalizability inherent to all survey-based studies with convenience samples. Specifically, LGBTQ+ individuals recruited from Pride events may be more willing to disclose their identities and be more socially connected than LGBTQ+ individuals who do not attend Pride events. Therefore, LGBTQ+ individuals who participated in the needs assessment may have been more likely to report discrimination and violence outcomes and less likely to report mental health outcomes than LGBTQ+ individuals who did not. Further, all data were self-reported and may be biased due to recall and/or social desirability. The analysis is also limited by a lack of specific cancer-related information including treatments received and time since diagnosis. Further, we were unable to use reliable measures of rurality such as rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes, as zip codes were not collected. Lastly, many of the outcomes in this analysis are subject to the influence of social desirability, which may suggest under-reporting of some outcomes, such as substance use and mental health outcomes.

Conclusion

Due to anti-LGBTQ+ stigma and discrimination, many LGBTQ+ populations experience poor physical, mental, and financial health outcomes. Being diagnosed with cancer introduces another layer of health impacts that may worsen the health of LGBTQ+ cancer survivors. Findings from this study, via the North Carolina LGBTQ+ Health Needs Assessment, revealed that LGBTQ+ cancer survivors were more likely to experience discrimination, violence, substance use, and overdose outcomes than LGBTQ+ individuals without a cancer history. These findings highlight a major gap in research and services aimed at understanding and preventing dangerous and often life-threatening outcomes among LGBTQ+ cancer survivors in North Carolina.

Disclosure of interests

The study team does not report any conflicts of interest.

Financial support

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes. Austin R. Waters is supported by the National Cancer Institute’s National Research Service Award sponsored by the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina (T32 CA116339).

.png)

.png)