Introduction

School health services benefit the health and well-being of students and their families.[1] They reduce barriers to access and provide physical and mental health care that promotes safe and supportive learning environments. But in the aftermath of disasters like Hurricane Helene, those services become even more vital. Six months after Helene, school operations in Western North Carolina (WNC) have mostly returned to normal, but the services provided at school are still playing an important role in the recovery.

Supporting the mental health of children following a disaster like Hurricane Helene is a major task for school health services. Children are often at increased risk of developing post-traumatic stress (PTS) or other symptoms of emotional distress. The traumas they might have experienced during a disaster include losing loved ones or friends, the loss of a home or personal belongings, or witnessing the devastation of their neighborhood. The support of their family and community can help to mitigate the challenges facing children and young people after a natural disaster, but mental health services are also of great help during those moments, and schools are often the best place to access those resources.

Youth Mental Health at Risk After Hurricanes

A strong body of research links hurricanes and other natural disasters to higher levels of emotional distress and mental health challenges in children. One study found that, following Hurricanes Andrew (South Florida, 1992), Charley (Southwest Florida, 2004), Ike (Gulf Coast; Texas, 2008), and Katrina (Louisiana, 2005), around 36% of children exhibited severe or very severe PTS symptoms within the first 3 months.1 Two years later, 1 in 10 children still showed signs of PTS.1

While most students’ symptoms decreased over time, about one-third of children reported stable, moderate symptoms immediately after and in the months following the hurricane; about 10% reported high distress levels that worsened.1 Elementary school-age children (kindergarten through 5th grade) were most likely to experience negative mental health impacts from these hurricanes.1

Other research confirms the prevalence of emotional distress among children following disasters. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina’s destruction, researchers found elevated PTS symptoms as high as 72% among groups of students in the immediate aftermath.2 Eight months after Hurricane Ike, nearly 1 in 6 elementary school students evaluated for emotional distress displayed PTS symptoms, and about 11% reported depressive signs.3 One in 10 elementary schoolers showed comorbidities of both PTS and depression.3 More than a year later, comorbidity levels remained the same in the sample of students, with only about one-third recovering 15 months post-disaster.3

Given the level of destruction and isolation caused by flooding in Western North Carolina during Helene, the number of children who experienced emotional distress is likely vast. This stresses the importance of mental health support for Western North Carolina children and students, which schools can help deliver.

Helene-Related Stressors and the Youth Mental Health Crisis in Western North Carolina

Prior to Hurricane Helene, North Carolina already faced a youth mental health crisis, and the associations between children’s emotional distress and hurricane-related stress exposures suggest these trends could worsen in Western North Carolina. In recent years, there is a growing degree of poor mental health indicators such as sadness or hopelessness among high school youth in North Carolina. In 2023, nearly 40% of North Carolina high schoolers reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness—a far higher proportion than a decade ago.4 The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to some of the recent increase in shares of high school youth with persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness; however, these levels were rising even before the pandemic.

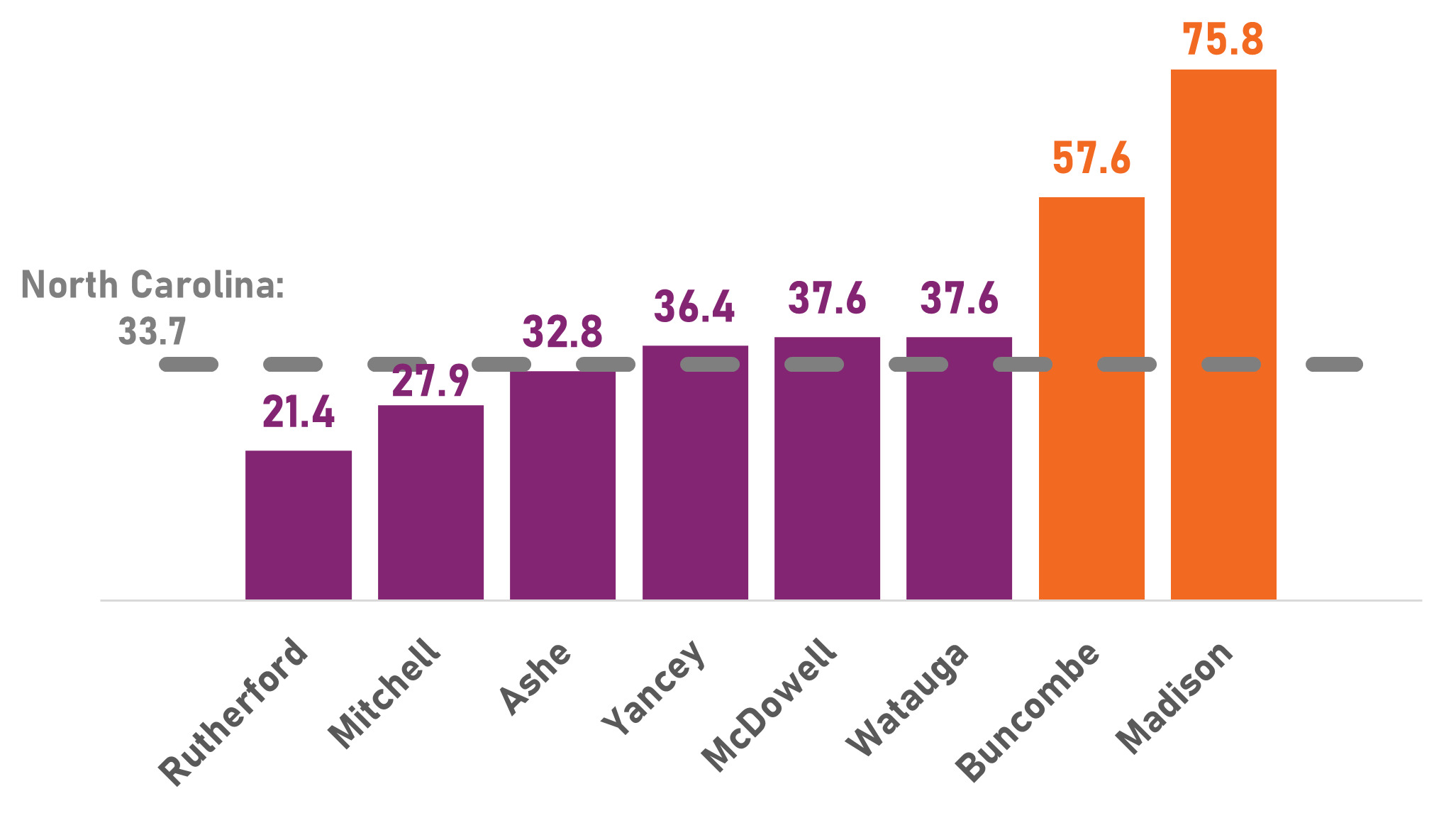

Without appropriate mental health support or treatment, youth resort to self-harm or suicide that can result in hospitalization or lives being cut short. The number of suicides among children ages 10–17 in North Carolina in 2023 was nearly 2.5 times the number in 2010.5 In the same year, nearly 1 in 10 (9.5%) of high school youth in North Carolina attempted suicide.6 In most counties hit hardest by Hurricane Helene, rates of pediatric behavioral health visits to emergency departments are higher than the state overall (North Carolina Healthcare Association data). In Buncombe and Madison counties, these rates are 1.71 and 2.25 times higher, respectively, than the state’s rate overall (Figure 1).

Data on the prevalence of youth mental health challenges at the county level for the overall child population are generally not available. Medicaid claims data gives us some idea of the type of behavioral health struggles among children with Medicaid coverage in Western North Carolina. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, or depression are typically the highest diagnosed psychiatric disorders among children with Medicaid coverage in these counties, as they are at the state level overall.7 However, rates of trauma diagnoses among these children are generally higher than among all children with Medicaid insurance in North Carolina.7 As noted above, PTS or stress-related challenges are some of the most common behavioral issues among children after hurricanes, and these rates likely rose in Western North Carolina in the aftermath of Helene.

Schools as Vital Hubs for Mental Health Treatment Pre- and Post-Hurricane

School-based services can help mitigate the potential negative impacts on children’s mental health from Hurricane Helene. School districts across the state provide mental and behavioral health services to students with varying levels of need. From broad-based curriculums that promote mental health in general classroom settings to group and individual counseling, schools often fill in gaps or supplement community-based mental health services, especially for students who might otherwise struggle to access private mental health care.

In the past 8 years of the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) Healthy Active Children Survey, local School Health Advisory Councils ranked mental health as their top priority (DPI unpublished data).8 School districts have struggled to meet the rising mental health needs of students, Western North Carolina districts included.

Following disasters like hurricanes, schools become even more essential to providing children with the services they need. Post-disaster, school-based services partially include creating spaces for students to maintain a sense of community connection and ensuring school staff have training to help them grapple with difficult emotions. For example, school staff trained in Psychological First Aid for Schools (PFA-S) can help students develop the coping skills and support they need in the immediate aftermath of disasters.9

While schools provide opportunities for children to maintain a sense of community post-disaster and can offer soft-touch interventions, many students will need direct and often more intensive interventions. Research shows direct and intensive interventions have been effective for children that need them. One randomized controlled trial of grief and trauma interventions post-Katrina found decreasing levels of mental health challenges among children that participated in group or individual counseling.10 To provide these more intensive treatments, schools need mental health professionals, either through school-based staff or through community partners.

In Western North Carolina school districts, there are generally not enough school-based mental health professionals to meet students’ needs (Table 1). The National Association of School Psychologists recommends a ratio of 1 school psychologist to every 500 students. None of the Western North Carolina school districts in counties hit hardest by Hurricane Helene meet this recommendation; McDowell, Mitchell, and Yancey County schools have no school psychologists (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction data). Similarly, none of these districts meet the 250:1 ratio of students to school social workers recommended by the School Social Work Association of America (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction data).

Schools in Western North Carolina cannot address the mental and behavioral health needs of students in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene without the necessary resources and workforce. Some districts, especially more populous, urban areas like Asheville and Buncombe County, can fill gaps in their school-based instructional support workforce with community-based providers. Yet most counties in the region do not have the local workforce to turn to. For example, in 6 Western North Carolina counties, there are 1 or fewer psychologists per a population of 10,000 people, and there is no guarantee that they specialize in pediatric behavioral care or serve children (Figure 2).11 This means school districts in Western North Carolina have limited community-based partners to offer school-based services, and private providers that are available may be stretched thin serving schools in multiple counties.

Unaddressed Emotional Distress Post-Disaster Poses Risks for Academic Recovery

A 2022 report from the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) suggests that academic recovery following natural disasters first requires student emotional recovery.12 We know from other research that student achievement in Eastern North Carolina communities dropped following Hurricanes Matthew and Florence. University of North Carolina researchers found clear negative impacts on elementary math and reading scores in 15 school districts heavily affected by these hurricanes, which persisted for 3 years after the storms.13 Many of these students likely dealt with the same PTS, depression, anxiety, and other behavioral symptoms that Western North Carolina children are grappling with right now.

Resources and Initiatives to Improve School-Based Mental Health Post-Helene

The second disaster recovery legislation passed by the General Assembly in 2024 allocated $5 million for mental health support in school districts impacted by the hurricane, including funds to provide assessments, treatment, or counseling.14 However, as of the State Board of Education’s March 15, 2025, report to the General Assembly, only about $19,000 of these funds had been spent—and only in Madison and Yancey counties.15 NC Medicaid also allowed flexibilities around school-based telepsychiatry and mental health services, though some of these have expired.16

Private providers are also ramping up efforts to serve students in schools. Blue Ridge Health operates school-based health centers in 7 Western North Carolina counties, offering both physical and behavioral health services to students. AppHealthCare operates similar centers in Ashe and Alleghany counties.

School-based telehealth providers like the Center for Rural Health Innovation’s (CHRI) Health-e-Schools program have and will continue to be vital in children’s emotional recovery. CHRI’s program offers physical and behavioral health services to students in Avery, Burke, Caldwell, Madison, McDowell, Mitchell, and Yancey counties through providers across the state, which allowed them to maintain services in the days immediately after Helene.

Conclusion

Supports thus far have been instrumental in caring for children in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, but research suggests that, for many students, mental health needs will persist in the years to come. Western North Carolina already faced a high and growing level of youth mental health challenges before the hurricane; a lack of resources and an adequate workforce in the region has made it challenging for schools to keep up with children’s needs. As Western North Carolina continues to recover from the storm, it is crucial that resources are available to address these challenges and that schools offer ample opportunity to deliver services to students where they spend some of the most important hours of the day.

Acknowledgments

NC Child would like to thank various state and local partners for their support in providing data and guidance in the development of this article, including the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s Healthy Schools Section, the North Carolina Healthcare Association, Amanda North and the Center for Rural Health Innovation, and the North Carolina Institute of Medicine. Additionally, we extend our sincere gratitude to the countless individuals, school districts, organizations, and communities working to support Western North Carolina children and families in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

Disclosure of interests

The author has no interests to report.

Financial support

The author has no financial support to declare.

This article refers to K-12 education when using “schools” throughout.