Introduction

Cannabis has been illegal at the federal level in the United States since 1970, when it was classified as a Schedule 1 drug.1 Many states moved forward with decriminalizing cannabis and regulating its use for medical and recreational purposes. However, the passage of the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 removed hemp-derived cannabis products containing less than 0.3% delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) from the Schedule 1 drug designation. This effectively made cannabidiol (CBD) legal at the federal level and led to a surge in the production and sale of hemp-derived cannabis products.2 North Carolina’s current policy follows federal regulations by allowing CBD/low-THC cannabis.3–7 However, North Carolina does not have rules regarding the sale and marketing of CBD products.

Little is known about the marketing of CBD products in brick-and-mortar retailers. Existing research has focused on online CBD marketing, where there is evidence that CBD is marketed to treat a variety of health conditions with unapproved therapeutic claims. For example, a broad study focusing on U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning letters sent to CBD companies found that products were marketed as food products, as dietary supplements, and were marketed with unapproved therapeutic claims for over 120 health conditions, including cancer, diabetes, and arthritis.8 Additionally, 39.4% of websites for CBD retailers made health claims and used product descriptions, such as natural and pure, to signal the products as safe or healthy.9 Importantly, product descriptors have been shown to impact consumers’ willingness to try the product, as well as their purchasing behavior.10

Despite the substantial marketing of CBD as treatment for myriad health conditions, the FDA has only approved CBD as the drug Epidiolex to treat childhood epileptic syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS).11 The FDA has not approved CBD to treat any other health conditions. Thus, marketing CBD with unapproved therapeutic claims is a significant public health concern, as it can potentially influence consumers to use CBD-containing products instead of critical, evidence-based medical interventions for their health conditions. In addition, there is a risk of potential drug interactions with other medications, as one study found that 30% of CBD users report taking CBD in addition to an existing prescription or over-the-counter medication.12

Data from a 2019 cross-sectional study focusing on the use and perception of CBD products in the United States and Canada found that 26.1% of US respondents reported using CBD in the past year, and 14% in the past month. Approximately 62% of the respondents used CBD products to manage medical conditions. Consumers reported CBD use for various mental health conditions, including anxiety (49.7%), depression (33.2%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (14.6%). Consumers also reported CBD use for physical health conditions, including pain (50.8%), headaches/migraines (32.6%), and trouble sleeping (27.2%). Almost 60% of CBD consumers in the United States and over half of those in Canada believed that CBD oil was good or very good for their health.13

While evidence is growing about the online marketing practices of CBD, research that investigates the content of CBD advertising among brick-and-mortar retailers is lacking; 74% of CBD consumers report purchasing products at brick-and-mortar retail locations.12 The goal of this pilot study was to systematically document CBD advertisements to understand the use of product descriptors and health conditions used in CBD advertising among brick-and-mortar retailers.

Methods

In November 2020, we conducted observational assessments of CBD retailers located in 3 North Carolina cities with populations from 114,000 to 300,000 people.14 CBD retailers were defined as specialty retailers that primarily sold CBD or hemp products. The study was reviewed by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) and deemed not human subjects research.

Sample

CBD retailers are not required to be licensed in North Carolina, and thus a complete list of CBD retailers was not publicly available. Therefore, we adapted sampling methodologies from previous tobacco/vape studies that have successfully used consumer-based directories (i.e., Yelp and Google) to identify retailers without licensing lists.15–18 Using this method, we identified CBD retailers by searching yelp.com using the keywords hemp, cannabidiol, and CBD. Retailer information, including name, address, phone, and operation hours, was collected. We excluded retailers that did not specialize in CBD, such as gas stations, vape shops, and vitamin/supplement shops.

Retailers were contacted to confirm that the business was open, hours of operation, and the types of CBD products available. CBD retailers were excluded if they were permanently closed or only offered curbside services due to COVID-19 restrictions. Thirty-two retailers were identified. After applying exclusion criteria, 16 retailers remained for in-store assessments. One was designated for data-collector training and 15 were visited for in-store assessments.

Data Collection

A team of two trained data collectors conducted the assessments. Previous tools used for assessing the marketing practices in cannabis and tobacco retailers were adapted for the assessment protocol, including the use of wearable technology.15,16 Using a mobile phone, one data collector documented characteristics of the store, products available, the presence/absence of age-of-entry and age-of-sale signs, and the presence of “No Photography” signs. Assessments were terminated if “No Photography” signs were present, since photos were required to document marketing.

The second data collector systematically documented advertising around the exterior and interior of the store in timed increments.16 Exterior assessments were conducted first; once complete, the interior was scanned, including countertops, shelves, walls, doors, floors, and windows. This methodology allowed data collectors to document the retail environment without relying on in-the-moment decision-making to code advertisements.16 The wearable device was set to capture one photo every 1.5 seconds.

After the assessment, data were downloaded to a laptop, reviewed to ensure photo clarity, and uploaded to a secure server. If photos were not clear, the assessment was repeated following the same procedures.

Photo Sorting

Once assessments were completed and the data were downloaded, photos were reviewed to identify advertisements specific to CBD. Duplicate photos, products that did not contain CBD, blurry images, price tags, and magazines were excluded. Photos with individuals were cropped to protect individual identity. The final database of images included all advertisements and product displays for CBD products.

Codebook and Content Analysis

A codebook was created for content analysis and focused on 1) product descriptors and 2) health conditions that the product claimed to prevent, treat, or cure (i.e., health claims). Product descriptors included those that described: 1) CBD in the product (i.e., full-spectrum, broad-spectrum, non-psychoactive, high CBD, whole plant); 2) CBD as healthy (i.e., organic, natural, non-GMO, healthy, gluten-free); 3) CBD as high quality (i.e., pure, clean, craft, premium, quality, enhanced); 4) CBD as having an effect (i.e., healing potential, relief, energize, and focus); and 5) scientific reference to CBD (i.e., science, science-based).6,14 Example advertisements containing coded product descriptors and health claims are presented in Figure 1.

Data Analysis

Two trained coders independently coded the photos using the codebook. Discrepancies were resolved by a third coder, the principal investigator. Frequencies were calculated for the health conditions advertised and descriptors used.

Results

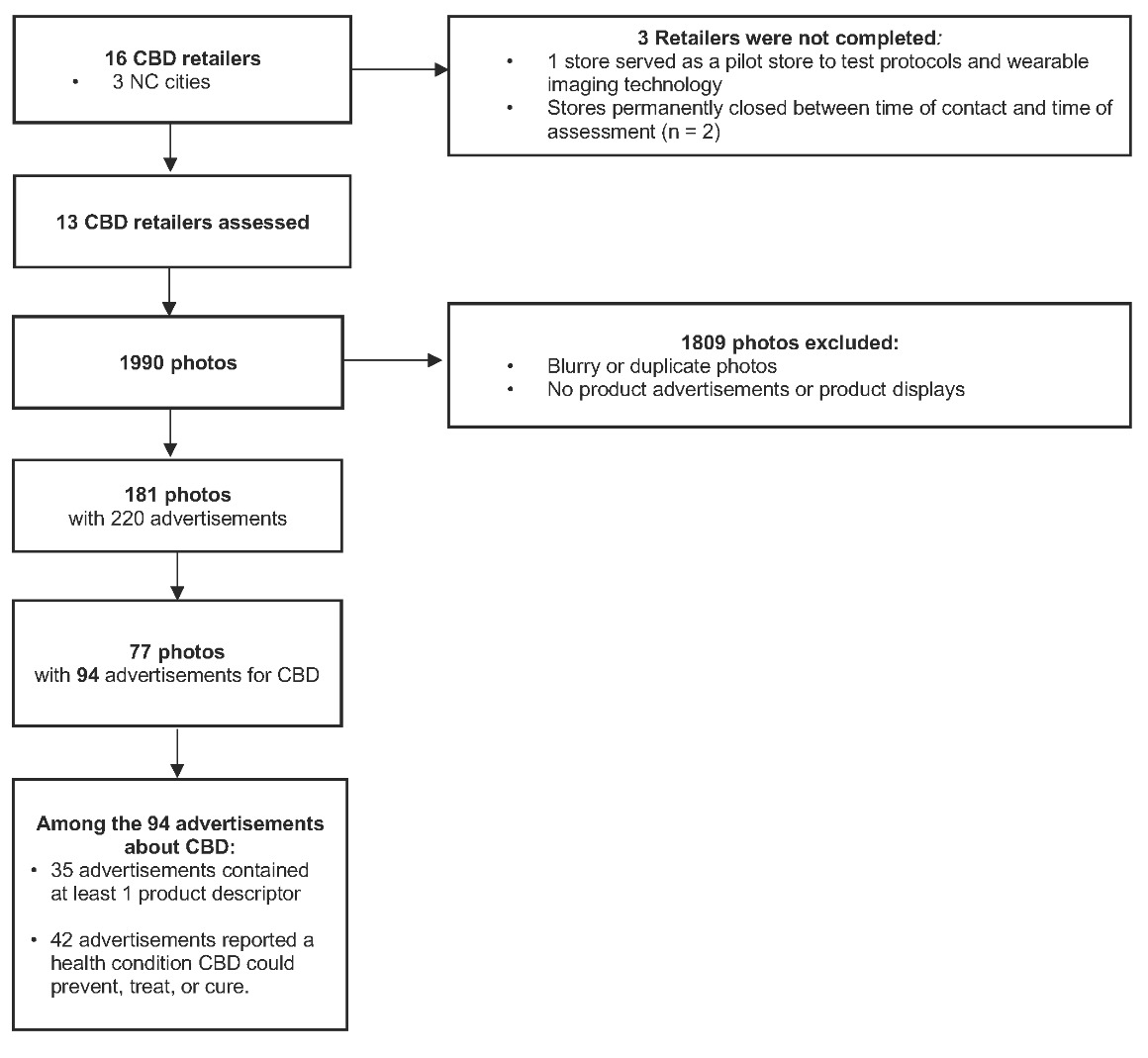

Assessments were completed at 13 of the 15 CBD retailers. Assessments for two retailers were not completed because the retailers permanently closed between the time the retailers were contacted and the time of the assessments. One retailer was used as a pilot store to test protocols and wearable technology. During the assessments, 1990 photos were taken across the 13 retailers. After applying exclusion criteria, we identified 220 advertisements in 181 photos, 94 of which were about CBD or CBD products (Figure 2). Retailers displayed 4–14 advertisements about CBD, with an average of 7 advertisements per retailer. Age-of-entry signs were posted in 30.8% (n = 4) of the retailers, and 15.4% (n = 2) of retailers posted an age-of-sale sign.

Descriptors

Product descriptors were documented in 11 (84.6%) retailers. Of the 94 advertisements about CBD, 35 (37.2%) contained at least 1 product descriptor. Product descriptors that describe the CBD used in the product were the most prevalent type of product descriptor (n = 17, 18.1%), followed by those implying CBD is healthy (n = 13, 13.8%). Descriptors indicating CBD as high quality (n = 9, 9.6%) and science-based (n = 2, 2.1%) were also documented. Descriptors describing the effect the consumer will feel as a result of CBD were documented in 4 (4.3%) advertisements. The most commonly documented descriptors were full-spectrum (n = 10, 10.6%), natural (n = 6, 6.4%), pure (n = 4, 4.3%), non-GMO (n = 3, 3.2%), and non-psychoactive (n = 3, 3.2%) (Table 1).

Health Conditions

Twelve of 13 retailers (92.3%) posted at least 1 advertisement that marketed CBD as a treatment for a health condition. Of the 94 advertisements about CBD, 44.7% (n = 42) contained a claim that CBD can be used to prevent, treat, or cure one or more health conditions.

Across all 94 advertisements about CBD, 39 unique health conditions were advertised. The most common conditions were anxiety/stress (n = 28, 29.8%), arthritis/fibromyalgia/ inflammation (n = 27, 28.7%), pain/neuropathy/neuroglia (n = 25, 26.6%), depression (n = 18, 19.1%), sleep/insomnia/apnea (n = 17, 18.1%), and cancer (n = 13, 13.8%) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is among the first to document CBD advertising in the retail environment. All retailers posted CBD advertising that contained either misleading product descriptors or unapproved health claims. Almost all retailers displayed advertisements that contained unapproved health claims (92.3%) and product descriptors (84.6%).

Over one-third (37.2%) of all advertisements contained at least 1 product descriptor; some of the most prevalent descriptors included natural and pure, which have been shown to reduce consumer risk perceptions for other substances, such as tobacco products.10 Although not thoroughly investigated in the marketing of CBD to determine how they may influence perceptions or behavior, these descriptors may imply to consumers that CBD is a healthy, safe, or high-quality product. More research is needed to understand how consumers interpret these descriptors for CBD. In addition, the terms full-spectrum or broad-spectrum are commonly used to market CBD products, but it is not known how consumers perceive these terms. Full-spectrum CBD has other naturally occurring cannabinoids, terpenes, and up to 0.3% THC, whereas broad-spectrum CBD has other naturally occurring cannabinoids and terpenes but no THC. The term broad-spectrum is used in marketing sunscreen to indicate that the product reduces harm by protecting the skin from harmful UV rays; it may influence consumer purchasing behavior, as 39% of consumers said they consider broad-spectrum when purchasing sunscreen.19 More research is needed to understand consumer perceptions of broad and full-spectrum CBD products and whether these terms impact consumer purchasing behavior or consumer perceptions of harm.

Many advertisements (44.7%) promoted CBD as an unapproved drug to prevent, cure, or treat a variety of health conditions for which it does not have FDA approval.11 While additional studies are needed to understand its medicinal potential,20 to date, CBD is only approved as the drug Epidiolex to treat rare forms of epilepsy, including LGS, Dravet syndrome, or tuberous sclerosis complex.11 Our findings are similar to those of a previous study that documented CBD being promoted to treat a variety of health conditions by online retailers.9 We documented 39 unique health conditions; importantly, conditions such as arthritis/inflammation (28.7%) and depression (19.1%) were advertised more frequently than the only approved condition, epilepsy (14.9%). These types of advertisements may influence consumers to believe that CBD is an effective treatment option for their condition, which may lead them to forgo evidence-based treatment for CBD alternatives.

Results from our study highlight the need for further surveillance of the marketing practices in the retail environment with a larger sample size, including retailers from both rural and urban areas and including more states with various cannabis policies. This study also indicates the need for the FDA and policymakers at the federal and state levels to enforce current cannabis policies aimed at marketing unapproved health claims in the retail environment.

There are several limitations in this pilot study. First, the assessment data is from November 2020, which was soon after the passage of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018. Importantly, policies focused on CBD/hemp policy have remained relatively unchanged in North Carolina; thus, findings are relevant to the current landscape of CBD advertising in North Carolina. Second, the small sample size of urban CBD retailers from one state limits the generalizability of study findings. Our sample only included retailers that specialized in the sale of CBD products despite CBD being sold in a variety of settings, such as vape shops and convenience stores. Given that cannabis legislation varies from state to state, it is possible that the legal landscape of state cannabis policies may impact marketing practices at the retail level, particularly in states where recreational cannabis is legal. More research in states with disparate cannabis laws is needed to better understand CBD marketing practices among brick-and-mortar retailers in both rural and urban settings. This will help paint a more comprehensive picture of CBD advertising in the United States and inform state and federal policymakers as they develop, refine, and enforce policies for CBD and cannabis on a broader scale.

Conclusion

This study is among the first to document CBD advertising in brick-and-mortar CBD retailers. Findings indicate that most retailers displayed advertisements that promote CBD as a treatment for health conditions not approved by the FDA and/or include product descriptors that indicate CBD is healthy or safe for consumers. These advertisements may reduce harm perceptions of CBD and influence consumers to replace evidence-based practices with CBD. Our findings underscore the need for continued surveillance and increased FDA enforcement of marketing practices in the CBD retail environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MaryBeth Dobbins for her work on this project. Additionally, we thank Dr. Romero-Sandoval for his expertise that assisted in the research.

Disclosure of interests

No competing financial interests exist.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.