Introduction

Hurricane Florence made landfall on September 14, 2018. As I sat on my couch watching the torrential rain, I realized I was seeking comfort in the news reports that Hurricane Florence would not significantly impact us. However, the rain continued, the electricity was out, and my cell phone was the only means of connection to the outside world. Then, the electrical service pole snapped, and the electrical wiring to my home was exposed in the street. My phone rang. The voice on the other end said, “This is going to get bad. We need help at a shelter. Do we need to send someone to bring you?” Surely, this cannot happen again! We are still recovering from Hurricane Matthew, with many neighborhoods closed, multiple families living in single-wide mobile homes, and local health care services seeking financial assistance after the storm’s impact.

Eastern North Carolina has experienced numerous named storms—in some years, as many as 3 storms. Every time, we heed the Emergency Services warning to prepare for 3 days of provisions with little to no help, counties set up command centers, and families seek help for members who require assistance to live. We start remembering that we have done this before and that we will get through this one more time. We recall the plans made after the last storm, wonder how many plans are now in place, and wonder if our ideas will work. Then we start to wonder what the tolls will be on our community—lives lost, safety-net services closed, educational and health care services distressed. As we fight the feelings of hopelessness, we know that the most vulnerable of us may not be able to fight it this time. Communities and populations that are distressed and have limited resources before the storm will experience the most severe impact and will need a longer time to recover.

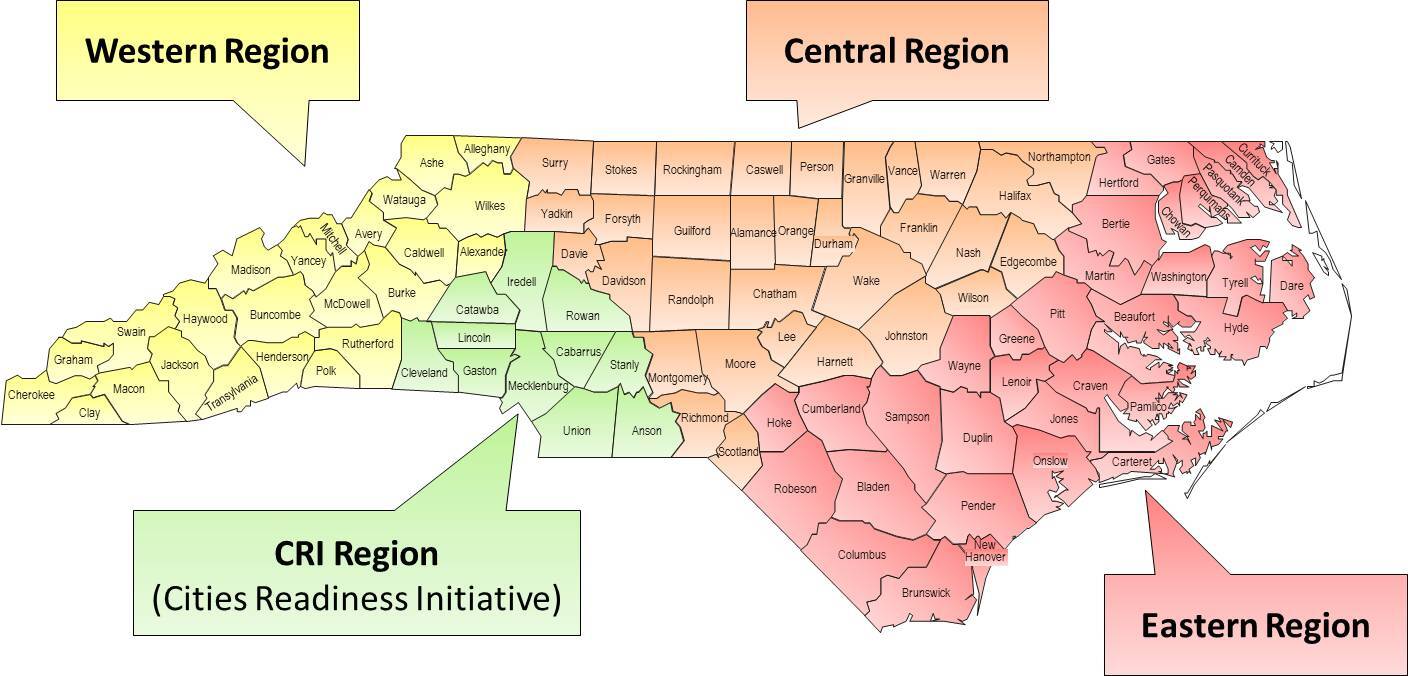

Eastern North Carolina

Eastern North Carolina is in the coastal plain region of the Atlantic Seaboard (Figure 1). Comprised of 41 counties, the topography consists of flat land, farmland, swamps, lakes, and estuaries—a complex ecological system that, combined with the latitude and longitude coordinates, accounts for the experience of a large number of storms (hurricanes, ice storms, tornadoes, and tropical depressions) and the patterns of water distribution. According to the North Carolina State Climatology Office (2006), an estimated 17.5% of all tropical cyclones have affected the state,1 with the Outer Banks often partially or fully submerged and other areas in the coastal plain impacted by wind, flooding, and the destruction of farming—especially waste retention ponds. The most recent tropical cyclone affecting Eastern North Carolina was Hurricane Debby in August 2024, resulting in flooding, road closures, and increased vector activity. Like other areas, storms most often have a negative impact on communities, populations, and ecological systems. The underlying health and well-being of the area’s populations must be considered.

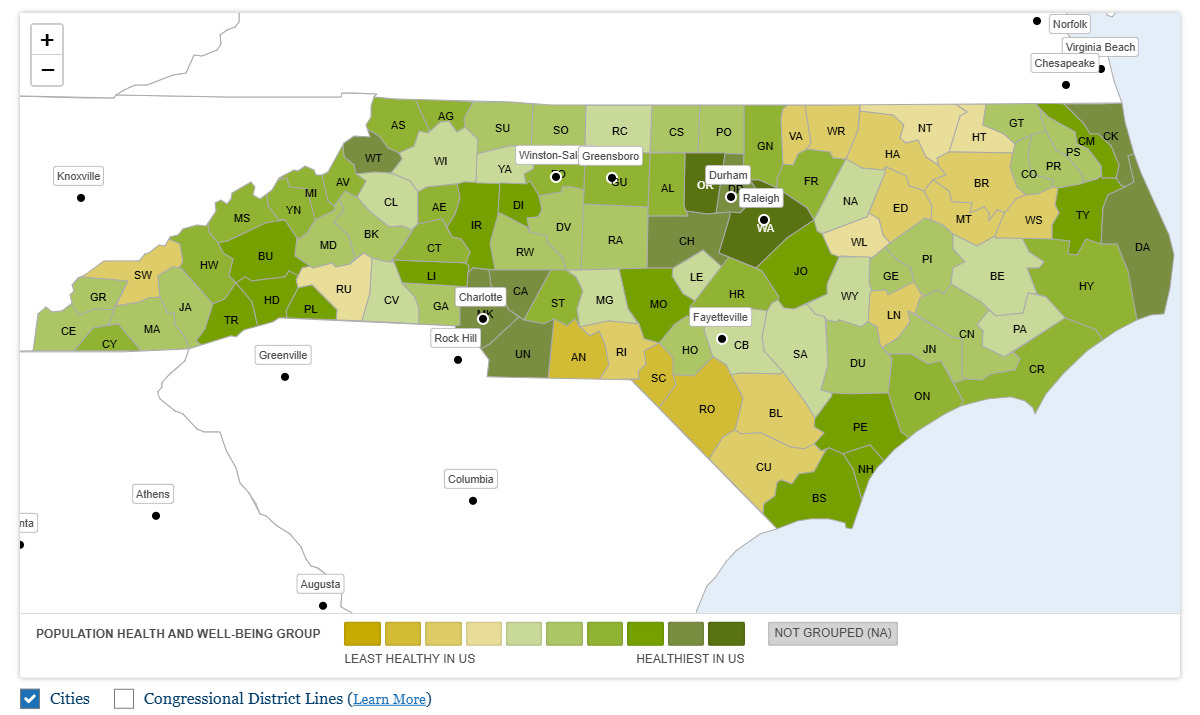

Eastern North Carolina and County Health Rankings

The impact of climate change (storms, floods, and extreme heat) is cumulative and has lasting influences on communities. To understand the effect of any one storm, the status of the communities before the storm must be considered. With only 5 cities with a population of more than 50,000, most of the 41 counties in Eastern North Carolina are considered rural. Most of these rural counties are home to populations with social drivers that lead to poor health and well-being outcomes. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings and Roadmaps Report provides an annual snapshot of the population’s overall health and factors influencing how well and long we live. The model uses more than 30 measures to aid in understanding health outcomes and what influences health in the future, while acknowledging that policies and programs at the local, state, and national levels are foundational to the health and well-being of communities. These health factors are divided into 4 categories, each weighted according to their influence on health. The most influential category is Social and Economic Factors (40%), followed by Health Behaviors (30%), Clinical Care (20%), and Physical Environment (10%).2 With a higher score indicating increased distress, a review of the County Health Rankings for 2025 reveals that people who live in Eastern North Carolina experience some of the poorest outcomes in the state (Figure 2). The presence of frequent storms may contribute to these poor outcomes by increasing the suffering of the communities.

Economic Stress in Eastern North Carolina

In addition to poor health, eastern counties are economically distressed. North Carolina’s Department of Commerce annually reviews and ranks each of the 100 counties based on economic well-being and relevant economic distress, with the goal of encouraging economic activity in the less prosperous areas of the state. Four factors are used for the assessment: average unemployment rates, median household income, percentage of population growth, and adjusted property tax base per capita. The 40 counties experiencing the most economic distress are classified as ‘Tier 1’; 19 have been aggregated in the southeastern and northeastern parts of the state since 2014. Furthermore, 13 of the 15 North Carolina counties that consistently appear as the most distressed are located in the eastern part of the state, all of which have a designation as rural.4 The improvement of health and health outcomes are not listed among the purposes of the Department of Commerce’s tier ranking, though these things impact the drivers of health. For example, an increase in tax base may indirectly indicate public versus private health insurance coverage or educational expansion. Median household income may indicate disposable income and access to healthy food, recreational facilities, and post-secondary educational attainment.

The communities located in these economically distressed areas experience higher unemployment rates, lower educational attainment, and food and housing insecurity. The demanding health care needs of rural areas, especially those with large underserved (including high-poverty, low-educational attainment) populations, are compounded by critical shortages in primary and specialty care providers and health and social services that provide care. According to the American Medical Association, while the need for more medical providers will be felt everywhere, the rural and historically underserved areas may experience health workforce shortages more acutely. Limited access to transportation also negatively impacts the well-being of the populations and communities in these counties.5

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and North Carolina Institute of Medicine’s “Healthy North Carolina 2030: A Path toward Health” task force report developed recommendations around 21 indicators to improve the health and well-being of North Carolinians by 2030.6 The report provides context, analysis, and recommendations that should be used to understand the challenges communities and populations face and provides targeted areas to improve population health before natural disasters add to their distress and challenges. The degree to which the frequent storms have been either the primary or secondary etiology of the education, economic, or health risks experienced by the communities in Eastern North Carolina has yet to be determined.

Diverse Communities in Eastern North Carolina

Another characteristic of Eastern North Carolina is the cultural diversity, which enriches the region yet adds to the complex mosaic of storm mitigation and recovery. According to the “25 Most Culturally Diverse Counties in North Carolina,” using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, many of the communities are home to culturally diverse populations. Counties are ranked by the highest Simpson’s Diversity Index score. Twelve of these counties are in the east, and 9 counties are designated as rural.7

Two populations—military populations and Indigenous peoples—require the development of complex partnerships among local and state governments and a specific government entity. Eastern North Carolina has a large military footprint, hosting installations representing 4 service branches. These military bases, located in 6 eastern counties, are significant in these communities, allowing families and businesses to thrive through synergy and partnerships.8 Yet, mitigation and recovery require military and federal agencies’ cooperation.

According to the 2020 US Census, North Carolina is home to the 6th largest Indigenous population in the United States, and more than 60% reside in the eastern part of the state.9 Only one North Carolina tribe, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians—whose homeland is located in the far western counties—receives direct federal benefits and has a designated reservation homeland. The other tribal communities have separate tribal governments that address the needs and well-being of the tribal members. Local and state government officials collaborate with these tribal governments to address population needs related to storms and other natural disasters.10 These collaborative efforts are hampered by the distrust that developed from trauma caused by years of discrimination and systemic racism.

Disruptions in Services

Natural disasters, whether named storms, excessive heat, or epidemics, disrupt services in all communities. However, this disruption has a more significant impact on communities in which essential services were limited prior to the disaster. This disruption impacts rural health and well-being, which, in the best of conditions, function with a limited health care and support workforce and with razor-thin economic resources. Disruptions of health care services increase mortality and morbidity, especially in populations that experience more significant health inequities, with limited available resources; repeated storms having a cumulative effect.

Lessons from Eastern North Carolina

One might wonder why the people and families still live there and proudly call these areas home. What lessons can these communities that have experienced numerous natural disasters, historically had more limited resources, and have large rural and underserved populations teach us? What positive attributes do these communities and populations possess that can be engaged and enhanced to better prepare for the future?

After years of working and researching in these communities, I have realized the importance of 4 attributes: a strong identity and belonging to place and people, a sense of resilience, a dependence on interconnectedness, and an attitude of generosity. A strong sense of identity and belonging provides strong social support, a sense of purpose, and a feeling of safety. Resilience—the ability to adapt positively to difficult situations—has developed as the communities and populations have bounced back from the challenges the storms brought, have innovatively adjusted, and have planned for the future. Communities and populations use interconnectedness to reclaim both the threatened identity and belonging often experienced in the midst of a storm, and they work together to plan for facing the next storm. Finally, the spirit of generosity and gratitude has often increased hopefulness and well-being. Inagaki and Ross reported in 2018 that targeted generosity resulted in a high sense of well-being and happiness.11 This may explain why members of groups who provide for each other before, during, and after a natural disaster appear to be doing well and express gratitude for what is left.

Just weeks after Eastern North Carolina had a minor brush with Hurricane Debby (roads closed, schools closed, work lost, crops and products destroyed, disruption of health and critical support services), our fellow North Carolinians in the West were severely impacted by Hurricane Helene on September 27, 2024. While we had started to prepare for Helene to turn east and had a brief sigh of relief when it did not, many in the East implemented our value and reliance on community traits of belonging, resilience, interconnection, and generosity by immediately mobilizing to support those in the West. While mudslides were foreign to the East, uprooted trees, destroyed homes, and lack of communication and electricity were not. Numerous work teams were formed, including health care workers, who took vacation time to help. Many others gathered supplies, collected funds, held prayer vigils, and sang songs for healing. The motto was and still is, “We have been there. We can help. This is going to hurt for a while.”

While we are in many ways two North Carolinas, we are one out of many. What can we learn from these community characteristics, and how can we enhance them through public policy and support? With previously labeled 50- or 100-year storms occurring every 3–5 years, we are required to look for a new paradigm of storm preparedness, recovery, and mitigation. Often, professionals meet to debrief and adjust plans, but it is in the community that we will find solutions that are community-driven, not professionally driven. While professional models are important, new paradigms that provide for more community control should be developed. Community members are the ones who open their doors and freezers to each other, share vacation time with work teams, and are there for the long haul. They have used community solutions to survive and grow for generations by blending their knowledge and processes with those of public health professionals, thus new models that allow for differences can be developed. Some questions to consider follow.

-

What are the best roles for the state, regions, and local communities? How do we help each become equipped for their role, including funding, training, and communication?

-

How do we support community-driven hotwashes that allow for community and population differences? (What do all communities have in common, and what are their different needs? Who is best to address these similarities and differences?)

-

What community and population characteristics impact the length of recovery? How can we use this information for planning and prevention?

-

Do our recovery plans include responding to increased heat and heat-related stressors, as many of these storms occur during the warmest months?

-

How could a state agency that works closely with communities and populations define common and specific goals and use innovation to prepare for the next disaster?

-

What would small, flexible, and agile community response teams look like, and how can they be incorporated into the state plan?

-

What are the metrics that a community or population would use to define and achieve recovery?

Conclusion

The frequency and severity of natural disasters in Eastern North Carolina warrants the development of new models to address disruptions to essential services—disruptions that compound with existing social drivers of health. Community identity, resilience, interdependence, and generosity must inform state and national strategies for professional and community-led disaster preparedness and recovery. As we face the reality of 100-year storms occurring every few years, it becomes clear that policy must evolve to prioritize and empower local voices. Supporting flexible, community-centered response models and addressing the underlying social drivers of health will not only mitigate the impacts of future disasters but will also enhance long-term well-being and equity for vulnerable communities.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my graduate intern, Mercedes Yanick, for her continued assistance.

Disclosure of interests

The author has no financial support or conflicts of interest to declare.