Introduction

Hurricane Helene, one of the most catastrophic storms to impact the US mainland since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, brought unparalleled devastation to Western North Carolina—a region unaccustomed to extreme weather events. Essential services were paralyzed as regional water systems collapsed, leaving residents without reliable or clean water access for several weeks. Helene’s impact has only magnified existing challenges in maternal health, exacerbating longstanding disparities in a field already under strain in this rural region, a maternal care desert marked by significant OB/Gyn clinic closures and maternity wards that limit access to essential maternal and prenatal services.

The storm is responsible for at least 250 fatalities in the United States (including at least 176 direct deaths), making it the deadliest hurricane in the contiguous US since Katrina in 2005.1 However, the full impacts of these tropical storms are not well accounted for, and recent evidence reveals that their effects persist long after the initial devastation, leading to excess mortality rates for up to 15 years post-storm, particularly among vulnerable groups such as infants, low-income residents, and communities of color.2

These long-term health consequences underscore the need for a more comprehensive approach to disaster recovery that addresses immediate relief and sustained support for at-risk populations. Here, we advocate for a focus on pregnant women and children, as these groups are particularly susceptible to both immediate and long-term health effects of environmental disruptions, including increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and mental health challenges.3–6

Maternal Health Services in North Carolina

Before Helene, maternal health services in Western North Carolina were already insufficient due to a severe shortage of health care providers specializing in obstetrics and gynecology, compounded by the closure of hospitals that offered obstetric care, such as the 6 labor and delivery units that have closed since 2015. The rural and mountainous landscape of the region, coupled with high poverty rates and limited transportation, pose significant barriers to accessing care, often forcing pregnant women to undertake long travel times to receive necessary services. According to data from the March of Dimes—a maternal health advocacy organization that tracks health data from various federal sources—before the hurricane, only half of the local facilities offered prenatal and delivery care for the region’s approximately 153,000 women aged 18–44.7

The consequences of such limited access are well-documented; women in rural areas are more likely to forgo prenatal care, which can lead to severe health complications, including severe maternal morbid conditions like preeclampsia and hemorrhaging.8–10 Hurricane Helene’s destruction has further isolated rural communities, leaving expectant mothers at heightened risk as they struggle to access critical prenatal and postpartum care.

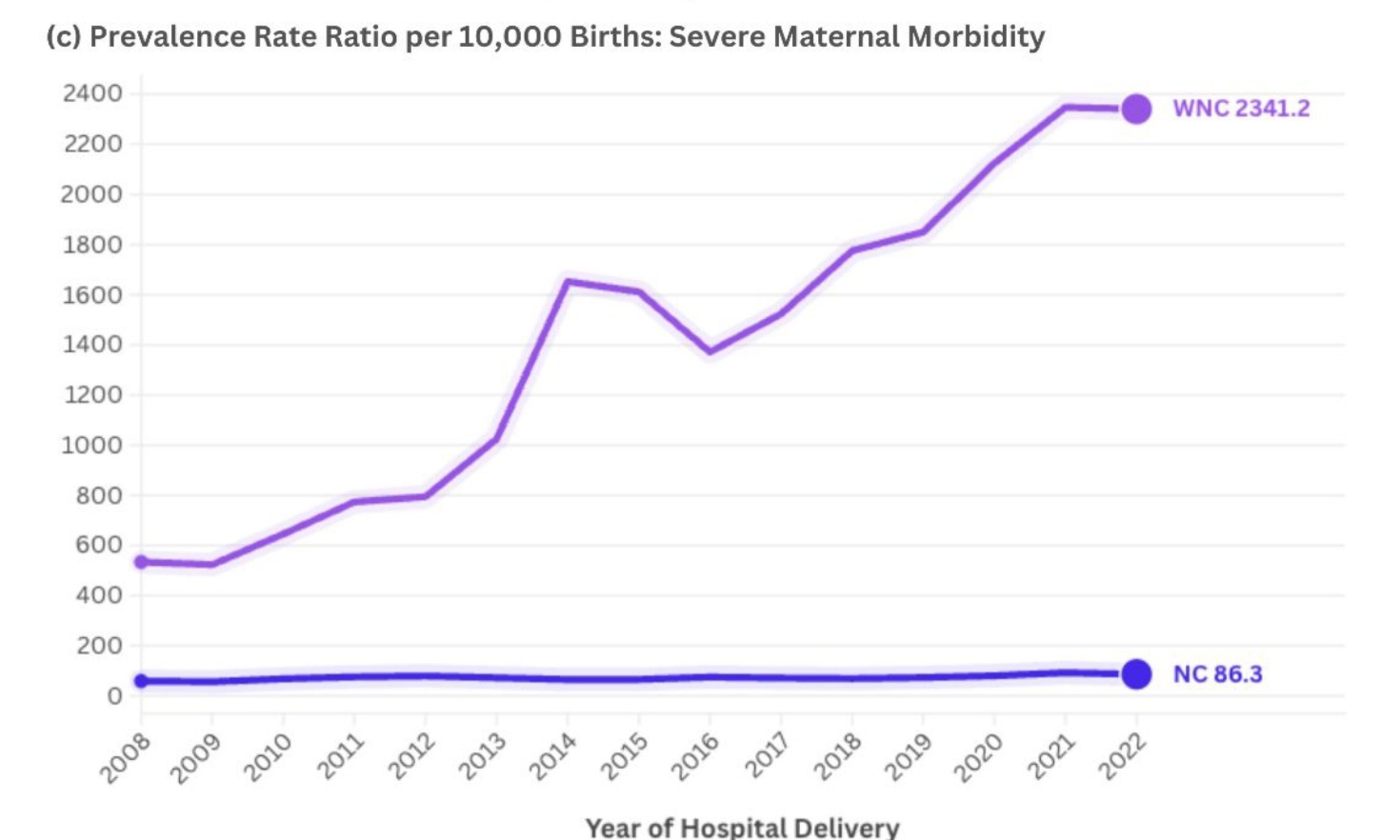

These disruptions significantly elevate the chances of maternal and infant complications, posing profound implications for families across Western North Carolina and deepening an already dire health care crisis in the region. Notably, even before the storm, maternal mental health, severe maternal morbidity, and substance use rates in Western North Carolina far exceeded state averages (Figure 1).

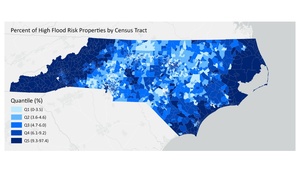

Climate disasters like Helene amplify these underlying maternal health disparities. Despite the region’s high number of properties vulnerable to flooding, most homes lack flood insurance through programs like the National Flood Insurance Program (Figure 2), adding to the economic strain on affected families.

The impacts of Helene underscore the urgent need to address Western North Carolina’s pronounced health disparities, particularly in maternal mental health and prenatal care. This ongoing disaster highlights the urgent need for targeted policies that address the specific vulnerabilities of pregnant women and their developing children, as pregnancy represents a critical window in environmental stressors, adaptation, and resilience.11 For instance, the prenatal period is particularly susceptible to climate extremes, as it involves rapid psychological and physiological changes in both mother and fetus, amplifying the impacts of climate-induced stressors.12

This stage also provides an essential opportunity for interventions, as pregnant women often have heightened access to health care (e.g., through expanded Medicaid) and may be especially motivated to enhance health behaviors in preparation for childbirth.11,13,14 In addition, existing research underscores that environmental stressors during pregnancy can have lasting effects on mother and child health.5,12

Addressing the Gaps

Despite the critical needs of pregnant women and infants in disaster contexts, policy frameworks often lack an emphasis on resilience-promoting measures for these at-risk populations. This oversight results in significant gaps in mental health support, access to safe housing, and continuity of maternal health care services.

To partially address these gaps, we recommend:

Strengthening health and maternal care infrastructure. Emergency response plans should include tailored prenatal and maternal services, mental health support, and provisions for high-risk pregnancies to ensure safety during and after disasters.

Enhancing data collection. Improved systems are needed to track short- and long-term health outcomes for pregnant women and children post-disaster, enabling the design of effective, responsive interventions for future extreme weather events and disasters.

Expanding access to mental health resources. Policies should incorporate post-disaster mental health screenings and interventions, as these groups often experience significant psychological impacts.

Ensuring continuity of care. Disaster response should prioritize maintaining prenatal check-ups and early childhood programs, especially for vulnerable, single female-headed households that face greater socioeconomic challenges.

Addressing housing and food security. Policies should go beyond immediate aid to ensure long-term housing stability and sustained nutritional support, as displacement and disrupted food supply chains severely impact prenatal and early childhood health.

Securing funding for long-term recovery. Resources should be allocated for long-term aid to support the ongoing health and development of pregnant women and children who remain at risk for months and years post-disaster.

Community health workers (CHWs), doulas, and midwives have expertise that can be invaluable before a disaster strikes. Investing in these roles provides a high return in community health and resilience. They can play an essential role before, during, and after disasters like Helene by preventing costly health complications through early intervention, education, and regular monitoring. As trusted community members, these embedded health workers can educate on potential health risks and connect families to critical services. They serve as first responders, delivering on-the-ground primary health care, assessing needs, and offering emotional support and mental health first aid.15,16 These professionals act as navigators for displaced or isolated families due to damage to roads, clinics, or hospitals, ensuring that at-risk populations—those most affected by disasters and least likely to have access to health care—receive the care they need.

Conclusion

Implementing new care models and policy measures will strengthen health care resilience, ensuring pregnant populations and children receive the support needed to mitigate immediate and long-term health impacts from climate disasters. By prioritizing maternal health in disaster recovery and strengthening health care infrastructure, we can reduce health disparities, support vulnerable populations, and foster a more resilient and equitable response to future climate events.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support

This work was supported by grant 1R03ES031228-01A1 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

_perinatal_mood_and_an.jpeg)

_perinatal_mood_and_an.jpeg)