Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted health care delivery.1 Across the United States, many non-emergent health care visits were either deferred or rapidly changed from in-person visits to telehealth visits. While clinicians urged the prioritization of contraceptive care during the acute phases of the pandemic, studies point to an overall decrease in contraception use during the pandemic.1,2 It is not clear whether this was due to a change in patients’ pregnancy goals, the implementation of triage protocols to ensure safety and stewardship of scare resources, or other factors. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether there were changes in the type of contraception used due to barriers to in-person health care visits.

Single-visit initiation of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is patient-oriented, cost-saving, and considered a contraceptive best practice.3–6 While the use of LARC methods has increased over time, the impact of the pandemic on single-visit LARC placement remains unclear. Therefore, we sought to describe practice patterns associated with single-visit LARC in the 12 months before and 12 months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that across all University of North Carolina Health clinics in the state of North Carolina, fewer patients had single-visit placement following the start of the pandemic compared to before.

Methods

We conducted a planned analysis of a retrospective cohort study of 4599 patients who received LARC across a statewide health system in North Carolina between March 15, 2019, and March 14, 2021. As previously described, participants seeking care at the main campus hospitals and 82 outpatient clinics located in 10 counties across the state of North Carolina were identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for insertion.7 Members of the study team manually abstracted each health record, including identifying any preceding visits related to contraception (either in-person or telehealth within 6 months of the index visit). We excluded records that had documented the use of LARC within 6 months of the index visit and records in which the documented indications for LARC did not include contraception.

Our primary outcome was whether a patient received LARC within a single visit, which was defined as such if the encounter notes documented a patient’s desire for LARC, counseling and consent for placement, and subsequent LARC placement within a single visit. Telehealth visits for counseling regarding contraception before an in-person placement visit did not count as single-visit LARC placement. Prior to March 15, 2020, all visits were in-person. We included predetermined covariates based on prior published reports in relation to contraceptive decision-making and access.8–10

We first used descriptive analyses to understand any differences in patient characteristics before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We then used a single-series interrupted time series design with a regression model that included the average monthly rate of a single visit, the mean monthly rate change in the pre-COVID period, the pre/post gap in the average monthly rate at the event, the mean monthly rate change in the post-COVID period, and the interaction between time and the intervention.

Results

There were no differences in the demographic characteristics of the patients who received LARC before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). Of the 2446 patients receiving a LARC before the start of the pandemic, 1721 (70.36%) received the LARC within a single visit. Of the 2153 patients receiving LARC after the start of the pandemic, 1442 (66.98%) received the LARC within a single visit (odds ratio [OR] = 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75 – 0.97). Of the 711 patients who did not receive single-visit LARC after the pandemic, 102 patients had a previous telehealth appointment for contraceptive counseling. After adjusting for patient age, race, ethnicity, parity, insurance type, clinician specialty, clinician training, and clinic location, there was a decrease in the odds of receiving a single-visit LARC after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted OR [aOR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76 – 0.99). Common reasons for not receiving a single-visit LARC included clinical reasons such as technical difficulties or patient discomfort, requiring a patient to be within 5 days of their menstrual cycle, need for insurance verification, and need for the LARC device to be ordered. The frequency of these reasons did not vary before or after the pandemic.

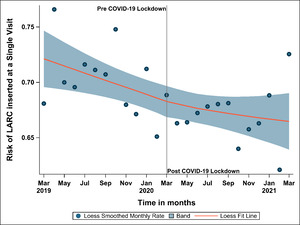

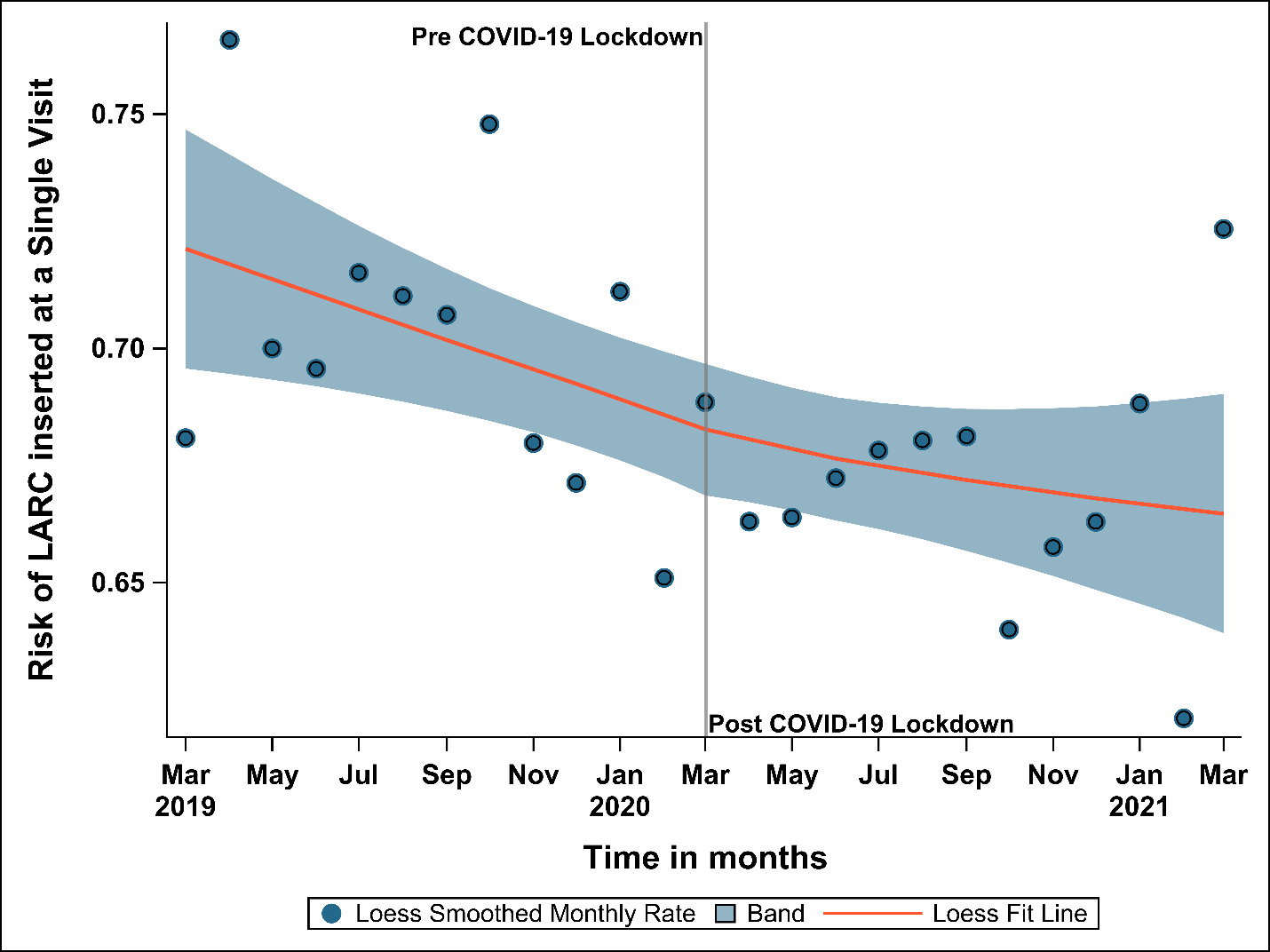

We depict the likelihood of receiving single-visit LARC by month in Figure 1, here described as “risk.” Overall, the risk of receiving LARC at a single visit remained high throughout, with a maximum risk of 76.6% in April 2019 and a minimum risk of 62.1% in February 2021. Before the start of the pandemic, the mean monthly risk of receiving LARC at a single visit was 0.72, with an underlying trend of a slight decrease per month (-0.003; 95% CI, -0.007 – 0.001). At our cut-off point in March 2020, we observed an immediate 0.018 (95% CI, -0.047 – 0.084) drop in the risk of receiving single-visit LARC. In the post-March 2020 time period, the trend of receiving LARC at a single visit had a slight decrease (0.001; 95% CI, -0.004 – 0.005).

Discussion

Among those patients who received LARC in a state-wide health system in North Carolina, rates of single-visit LARC decreased after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The overall number of LARC insertions and demographic characteristics of patients undergoing insertions stayed stable. Patients receiving LARC after March 2020 often had a telehealth counseling visit prior to their in-person insertion visit.

The rapid adoption of telehealth in the spring of 2020 has been associated with reduced barriers to contraceptive care, but also disparities in adoption.11,12 Use of telehealth for contraceptive counseling prior to an insertion visit may be associated with greater clinical efficiencies, the ability to utilize a potentially wider array of pre-insertion analgesia medication, as well as increased time for patient decision-making. Given ongoing changes to federal and state reproductive health policies, there has been increasing telehealth access for contraceptive care. Telehealth also offers an opportunity to discuss patients’ goals and expectations for analgesia surrounding LARC procedures, which has recently received additional attention nationally. However, the need for an additional health care visit may be associated with increased cost and serve as a barrier to care for some patients. This study provides an initial look at this trade-off between telehealth counseling and single-visit LARC placement. Further data are needed regarding this trade-off in terms of patient experience and satisfaction, LARC provision rates, the need for bridge contraception (temporary birth control methods) between telehealth care and LARC insertion, and rates of pregnancy given increased potential barriers to LARC care.

There remains room for improvement in addressing logistical barriers to single-visit LARC, such as ensuring device availability and streamlining insurance verification, as well as providing education that patients do not need to be within five days of their menstrual cycle. However, given the stability of such barriers to single-visit LARC before and after the pandemic, the bulk of the decrease in single-visit LARC after the pandemic is likely due to the increased use of telehealth for contraceptive counseling and care. This remains especially relevant post-pandemic given the continued national conversation surrounding LARC access in the face of restricted access to abortion care and increased attention to analgesia for LARC procedures.

Strengths of our study include a diverse patient population seeking care across an entire state. Limitations include electronic health record data-based abstraction of variables such as race and ethnicity. We were also unable to determine whether patients preferred a telehealth visit prior to an insertion visit. Additionally, we cannot draw conclusions for patients who sought care in other practices across the state or those who had an initial telehealth visit for counseling but did not undergo LARC placement.

Conclusion

There was a decrease in the rate of single-visit LARC placements after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic with a concomitant increase in the use of telehealth visits. Further data are needed to understand patient goals and experiences, as well as clinical and public health impacts surrounding the use of telehealth for contraceptive care, especially for methods that require in-person clinician involvement.

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Financial support

This project was supported in part by 1) UL1TR002489 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award Program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health; and 2) a research grant from the Investigator-Initiated Studies Program of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. Mary Carmody receives support from the CPC NICHD-NRSA Population Research Training: T32 HD007168 and an infrastructure grant for population research (P2C HD050924) to the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.