Current State of Health Care and Primary Care in the United States

The United States health care system has long been documented as the most expensive in the world, costing $13,432 per capita in 2023 versus an average of $7,393 in comparable countries.1 This translates to the United States spending over 17.6% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care in 2023, with an average GDP per capita growth rate of 8.7% since 2020. Not only do we pay more for health care, but we also lag behind other industrialized countries in key quality areas like access to care, outcome(s) measures, and administrative efficiency.2 Indeed, North Carolina leads the nation in health care costs with respect to employer-sponsored (i.e., self-insured) plans that have higher premiums and deductible rates compared to those in other states.

Health care costs are unsustainable, whether looking through the lens of a payer, an employer, a patient, or a taxpayer. This begs the question: how do we ‘bend the cost curve’ while improving access to care and health outcomes? This paper focuses on developing solutions to address cost and quality by enhancing the primary care infrastructure as a key foundation for creating a more accessible and affordable health care system for North Carolinians and our economy.

Comprehensive primary care as a solution in North Carolina is complicated by current physician practice trends. The current investment in US primary care stands at 4.7% of overall health care spending versus an average of 14% in other high-income countries.3 This leads to less bandwidth for primary care practices to coordinate care, provide chronic care management, and offer preventative care, which reduces the need for expensive specialist care and hospitalizations. Diminished investments result in fewer medical students choosing primary care. Combined with an aging population and a high number of currently practicing primary care physicians who plan to retire soon, these issues are contributing to a growing patient access and affordability challenge. In North Carolina, the Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) designation includes 93 of 100 counties for primary care. The 2024 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) workforce report projects a national shortage of 87,150 primary care physicians by 2037.4

Pharmacists as Primary Care Partners to Enhance Access and Outcomes

Pharmacists undergo extensive training to educate patients and consult with practitioners as medication experts. At the University of North Carolina (UNC) Eshelman School of Pharmacy, almost 90% of incoming students have completed an undergraduate degree at matriculation. Pharmacy school takes 4 years to complete, with introductory practice experience during the first 3 years and advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE) during the fourth year. Over 70% of UNC students complete postgraduate work through a residency or fellowship, and all students must pass a national board exam for licensure.

Pharmacists are medication experts. Optimizing medications is critically important when managing chronic conditions, vulnerable populations, and patients with complex conditions like cancer. More than 50% of Americans have at least one chronic condition, and most of these patients see multiple physicians. Given the fragmented nature of our health care delivery system, coordinating medications can be a huge challenge. The cost of medication-related morbidity and mortality can exceed $500 billion annually when considering overuse, underuse, and misuse of prescription drugs.5 Furthermore, the cost of medication nonadherence has shown to result in $100 billion in excess hospitalizations each year, illustrating the potential impact of pharmacists empowered to practice at the top of their licenses.6

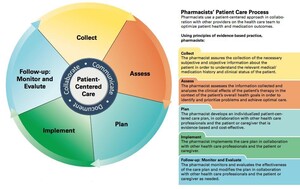

The pharmacists’ patient care process (Figure 1) was created by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) in 2014 to create a common framework for addressing patient care and medication management. These evidence-based principles engage patients to collect, assess, plan, implement, and provide follow-up in conjunction with physician oversight of that patient. With the patient care process in mind, pharmacists work with physicians across care to engage patients and optimize regimens. Identifying and resolving medication therapy problems (MTPs) is critical to improve outcomes, coordinate care, and work with physicians and other prescribers to resolve medication problems. This approach uncovers issues like adverse drug reactions (ADRs), nonadherence, medication interactions, incorrect therapy or dose, and others. Many studies have shown the impact of identifying and resolving MTPs on patient care.

Since pharmacists are not considered ‘providers’ through the Social Security Act, pharmacists cannot bill for their services, which leads to less uptake of these needed services. Many health care systems have identified the value of pharmacists and justify employing them to work with physicians to implement medication management services. This provides a natural collaborative relationship to work together on complex patients’ cases to optimize medication therapy and engage patients in care.

Expanding collaborative relationships beyond health systems to smaller practices in rural areas of North Carolina is a huge opportunity. However, the existing reimbursement model for pharmacy, which is tied to dispensing medications, is under serious threat. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) manage over 80% of all medication claims.8 The negative impact on pharmacy includes controlling where patients can fill their medications (network access) and determining medication reimbursement rates, which are often less than the acquisition costs. Over 100 community pharmacies have closed in North Carolina from 2022–2024.9 Evolving reimbursement models are critical for pharmacy and have huge benefits for physicians, payers, and patients.

In North Carolina, pharmacists can engage in an advanced practice license known as a Clinical Pharmacist Practitioner (CPP) license that allows a pharmacist to enter into a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) with a supervising physician.10 The CPP can write prescriptions, modify drug therapy, and order lab tests to optimize the patients’ medication regimen. Often the CPA revolves around chronic care management and involves complex patients. The CPP designation is authorized by the North Carolina Pharmacy and Medical Boards and has been in place for 20 years. With approximately 400 active CPPs in North Carolina, the regimented criteria and inconsistent reimbursement for services has limited the impact of CPPs collaborating with physicians. There are current legislative proposals in North Carolina to expand the CPAs so pharmacists and physicians have more flexibility around protocols, supervision, and expanding joint reimbursement.

Making the Case for Team-Based Care: Comprehensive Primary Care

Interprofessional practice (IPP) “happens when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, carers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings.”11 IPP requires that professions work together (with patients and families)—not simply in the same building. This requires sufficient time for communication and collaboration, clinic and workflow designs that support this collaboration, mutual respect, and supportive financial models that support interprofessional care. Nowhere is the need for interprofessional practice greater than primary care settings. Primary care, defined by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (now the National Academy of Medicine), is the “provision of integrated services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”12 Members of the health care team have historically included doctors, nurses, medical assistants, and physician assistants. Increasingly, pharmacists and behavioral health providers have become integrated into primary care. The job of primary care, in an increasingly complex health system, requires an integrated, team-based approach to address the medical (including pharmaceutical), behavioral, and social health of patients.

Training in an interprofessional environment is critical for teaching our current trainees to be prepared for IPP. In the case of medical residencies, most primary care residents work with pharmacists in hospital settings. Working with pharmacists in outpatient settings is less common. Less common still is training with pharmacy students. Interprofessional education (IPE) occurs when learners from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration.13 IPE allows learners to better understand the skills and roles of team members and enables effective communication during education and beyond. Pharmacists in medical residency programs play critical roles as team members and educators. Specific models of effective IPP can include consultation for polypharmacy, anticoagulation management, transitions of care, and team-based care of chronic conditions (such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma).14–18

As health care costs continue to outpace inflation, health systems and payers must invest in the most effective and efficient models of care, such as integrating pharmacy and primary care.19 Primary care practices manage multiple conditions in a single visit, leverage the expertise of the primary care team, and coordinate with specialists and community-based resources. High-functioning primary care is the foundation of high-performing health systems.20,21 The more that is spent on primary care, the healthier the population and the lower the cost. Many states, including North Carolina, have enacted or are evaluating regulatory approaches towards increasing the percentage of health care dollars spent on primary care to a minimum of 10%–12%.22,23 Increasing resources dedicated to primary care will allow a more robust investment in the team of professionals needed to address issues in care, keep people healthy, and keep costs down. As health care moves increasingly to value-based models of payment, health systems and provider organizations will be able to make local decisions about the best ways to deliver care. Rural practices are often small and may not generate sufficient demand for a CPP or other additional members of the team. Such practices may require different solutions to IPP, such as regional shared clinical services.

Making North Carolina “First in Health”: Policy Recommendations to Support Primary Care and Pharmacist Collaboration

A strong comprehensive primary care infrastructure is critical to solving many US health care problems around access and affordability. North Carolina is well positioned to advance team-based care with the following policy recommendations.

Interdisciplinary, Team-Based Training of Physicians and Pharmacists

Priority one is training the next generation of physicians and pharmacists together to build an interdisciplinary, team-based mindset from the beginning. Evolving graduate medical education (GME) in North Carolina should focus on the medical education neighborhood concept, which emphasizes community-based training with a focus on primary care and pharmacists, particularly in rural areas. The North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (NC AHEC) provide much of the needed infrastructure with regional hubs across the state. An integrated approach with strong leadership is important to establish an overall strategy to advocate for federal legislation, expand Medicaid funding and flexibility in the face of potential funding challenges, explore opportunities for private-public partnerships, and create processes for reporting and evaluation.

Expanding Collaborative Practice Policy

Priority two is providing physicians and pharmacists with a blueprint for collaboration to scale up team-based care by modernizing physician-supervised collaborative practice agreements. Updating the current collaborative practice policy and expanding the number of CPPs will in turn increase the number of supported physicians. The majority of CPPs currently work in large, urban academic practices. Modernizing collaborative practice includes simplifying enrollment criteria (the who), expanding the flexibility of protocols (the what) based on the supervising physician’s patient population, and providing a reimbursement path (the how) for physicians to bill for CPP services on behalf of pharmacists. Collaborative practice agreements increase collaboration and drive access to patient-focused disease management programs to address access and outcomes shortcomings, especially in the rural areas of North Carolina.

Interprofessional Recruitment for the Health Sciences Workforce Pipeline

Priority three is building the health sciences workforce pipeline through interprofessional recruitment activities. Investing in a structured and sustainable program for pharmacy, medical, and nursing students to engage high school students in rural areas through educational events and summer camps positions North Carolina for success and offers a long-term solution to rural health care access issues. A great example to build from is the Area L AHEC-sponsored Conetoe Family Life Summer Camp.24 Recruiting the future rural health care workforce by current interdisciplinary health care students is a win-win proposition that demonstrates team-based care at its finest.

Primary Care Payment Task Force

Priority four is to support the work, findings, and recommendations from the Primary Care Payment Task Force. A commitment from public and private payers to enhance the investment in primary care is vital to improving access and quality. For example, Rhode Island increased primary care investment from 5.4% in 2007 to 8% in 2011. At the same time, total medical spending decreased by 18%.25 Increasing primary care spending will give primary care the resources for high-quality interprofessional practice, enhance recruitment and retention for primary care, and improve access for North Carolinians.

These recommendations could have a dramatic impact on access, outcomes, and workforce shortages. Collaborative leadership is needed to unlock team-based care, which could elevate our state to “First in Health.”

Acknowledgments

Jon Easter and Adam Zolotor have no conflicts of interest to declare.