Introduction

Drug overdose continues to be one of the fundamental public health challenges of our time, in North Carolina and nationally. Since the start of the 21st century, more than one million Americans have died from drug overdose, with this drug crisis constantly evolving as new political, environmental, and societal shifts shape the landscape. In January 2020, the “Healthy North Carolina 2030” (HNC 2030) report was released, which included a goal to decrease drug overdose deaths from 20.4 to 18.0 overdoses per 100,000 residents over the following decade.1 However, HNC 2030 could not have accounted for the emergence of the global COVID-19 pandemic2 and a new trend toward polysubstance use3 that would drive the overdose epidemic to new heights. In 2020, overdose deaths jumped 40% in North Carolina, with marginalized and vulnerable communities carrying much of the burden.4 Overdose deaths reached a peak in 2023 at 40.1 overdoses per 100,000 residents,5 more than twice the target set by HNC 2030. Recent reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), however, have renewed hope, as overdose deaths began to decline significantly in mid-2023 for the first time in decades, with as many as 27,000 fewer fatal overdoses nationally in 2024.6 Though it is unclear what has caused this drop in overdose deaths, there are likely many factors at play,7 such as the efforts of public health practitioners across the state and country to increase the distribution of life-saving naloxone, access to evidence-based treatment, and recovery support services.

While we celebrate these accomplishments, we acknowledge the sobering reality that nearly 80,000 individuals nationally will die this year from overdose. Clearly there is still work to be done. In reviewing the first 5 years since HNC 2030 was put into action, it is evident that local data and actions are critically important; addressing this complex public health challenge will continue to require deliberate funding of harm reduction, treatment, and prevention interventions. In this commentary, we provide an update on the opioid settlements in North Carolina, describe our state’s progress in transparently tracking opioid settlement spending and impacts at the local government level, and highlight a tangible example of a drug analysis program that utilizes analytical chemistry to bring transparency to what is found in local drug supplies.

The Opioid Settlements in North Carolina

While drug overdose deaths were rising in North Carolina between 2020 and 2023, several of the largest national opioid settlements were reached. Nationally, more than $50 billion in national settlements and bankruptcy resolutions have been negotiated with opioid companies, bringing over $1.4 billion directly to North Carolina over an 18-year period.8 These funds provide financial resources to state and local governments to launch or expand interventions to address the opioid overdose crisis.

In North Carolina, 85% of the funds from most of the opioid settlements are disbursed directly to local governments in all 100 counties and 17 participating municipalities, with the remaining 15% controlled at the state level.9 Allocation of opioid settlement funds is governed by the North Carolina Memorandum of Agreement (MOA). The North Carolina MOA outlines the multistep process that local governments must follow to fund programs using opioid settlement dollars, including a list of allowable high-impact opioid remediation strategies covering treatment, recovery supports, harm reduction, prevention, and other evidence-based approaches.10,11

Transparency and accountability are fundamental to the success of the North Carolina model. Thus, tracking the spending and impact of opioid settlement funds is key to ensuring that locally driven expenditures improve health and reduce overdose deaths. Central to this effort is the Community Opioid Resources Engine for North Carolina (CORE-NC), a collaborative partnership between the North Carolina Department of Justice (NCDOJ), the North Carolina Association of County Commissioners (NCACC), the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center (IPRC), and the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS).11

CORE-NC works to ensure transparency of and accountability for the spending of opioid settlement funds by local governments in North Carolina. Each partner contributes their expertise to advance CORE-NC’s mission. NCDOJ enforces the North Carolina MOA,11 and NCACC and NCDHHS both provide technical support to participating local governments.12 The team at UNC IPRC leads data collection, processing, and visualization and maintenance of the CORE-NC website, with the goal to efficiently communicate how opioid settlement funds are being disbursed and the impact of these funds to the public.13

CORE-NC: Tracking Local Settlement Spending and Progress

The North Carolina MOA requires local governments to report their progress through several mandated reports which provide detail on planned spending, actualized spending, and the impact of spending for each local government.11 Public displays of these data allow for a deeper understanding of actions to address the opioid overdose crisis, provide for accountability in spending decisions, and provide an avenue for communities to advocate for efficient use of settlement funds.

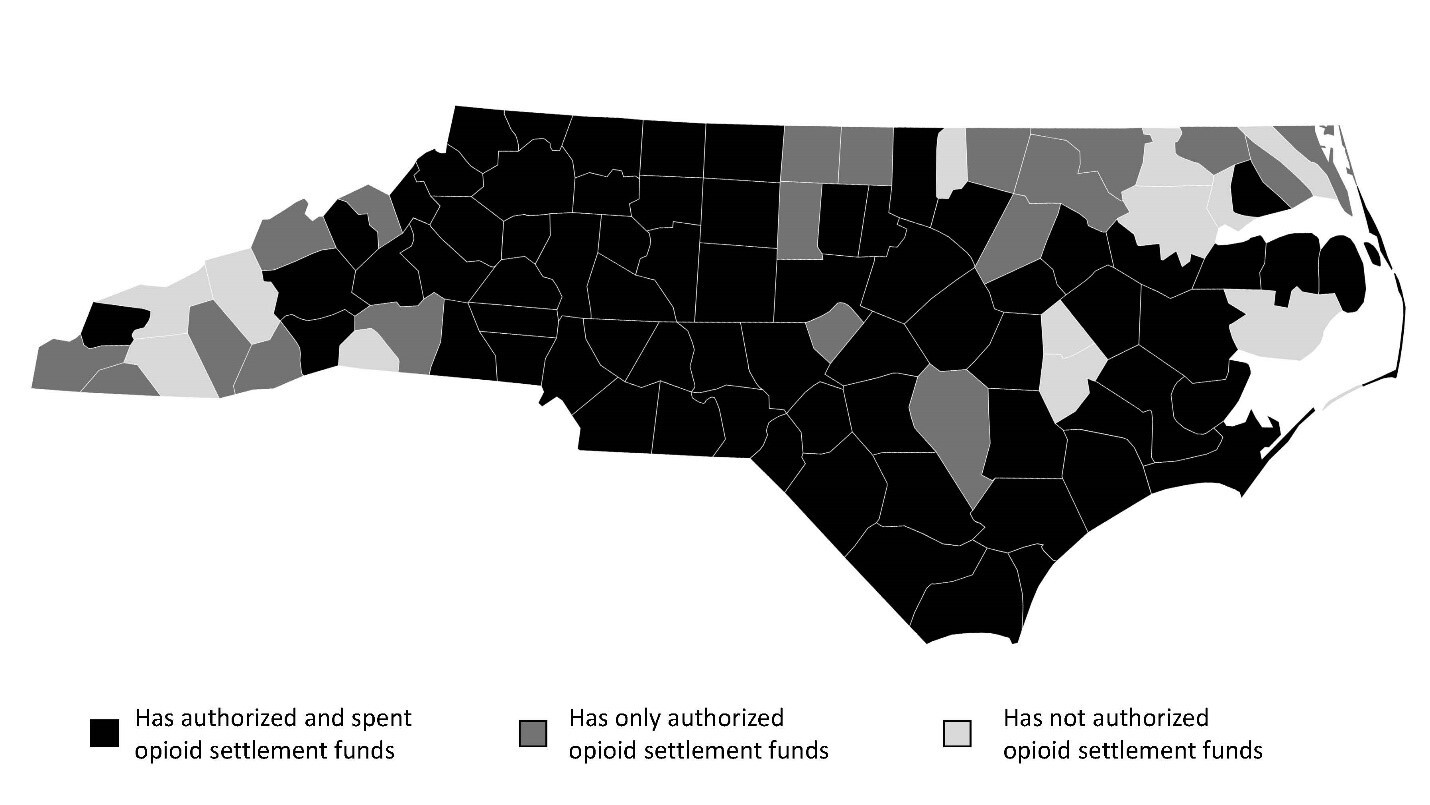

Before spending opioid settlement funds, each participating local government must first adopt a resolution or ordinance that authorizes all expenditures. Sufficient detail must be provided for each planned expenditure, including the specific opioid remediation strategies the local government intends to fund and the dollar amount and eligible spending period per strategy.11 As of June 2025, 97 local governments have shared opioid settlement spending plans (Figure 1). Strategies that have been prioritized for planned spending include recovery support services, naloxone distribution, and post-overdose response teams.14

Local governments must also report the actualized spending of opioid settlement funds each fiscal year. Between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2024, 75 local governments spent over $24 million of the available opioid settlement funds (Figure 2). Recovery support services and post-overdose response teams had the highest funding disbursements, at $5.9 million and $2.7 million respectively (Figure 2).15

Additional data is gathered about the impact of each settlement-funded strategy by fiscal year. Collecting quantitative and qualitative information allows local governments to evaluate the impact of their spending. CORE-NC collects each strategy’s implementation status, progress and success narratives, and evaluation metrics. Example evaluation metrics include: the number of naloxone kits distributed as a measure of equitable distribution or adherence to treatment after 6 months to track retention. Collectively, this information helps to contextualize the community-level impacts of programs. Most funded strategies to date are in the earliest stages of implementation.16 Though there is often a temporal delay between implementation and changes in population-level outcomes, process and quality evaluation metrics, along with narrative data, can provide information confirming the need for continued funding and informing future decision making. The availability of these data also helps local governments learn from neighboring governments that may be implementing similar strategies.

All reporting data are reviewed by CORE-NC for compliance and clarity, while technical assistance is available to improve data quality. This technical assistance includes the development of guidance documents to support reporting, in-person engagement opportunities for peer learning, and individual technical support.12 Once processed, we display data publicly on the CORE-NC website, updating quarterly or annually depending on the source. Additional details on settlement progress are available in the CORE-NC document library,17 which houses all official documents submitted by local governments. This repository is especially useful for local government staff, providing a complete census of all previously submitted reports. Together, the website and the document library are products of CORE-NC’s principle of transparency.11

It is too early in the estimated 18-year payout period to project the direct association between the use of opioid settlement funds and improved health outcomes like decreased drug overdose deaths. However, it is encouraging to see the continued prioritization of opioid settlement funding across the state and the community-driven solutions to the crisis. The opioid settlements present a unique opportunity to assess the impact of strategic investment in evidence-based programming over nearly two decades. As we collect more data on spending and impact, we will identify helpful trends across the state and lessons learned that can extend beyond the opioid settlement period and our state’s borders. North Carolina, through CORE-NC, is uniquely positioned to support local government autonomy over settlement funds while also collecting and disseminating data to improve the implementation of opioid abatement strategies.

Street Drug Analysis Lab (SDAL): Access to Advanced Drug Analysis

Another area that requires increased transparency is the chemical composition of what is in our drug supply. Test strips provide a reliable means of quickly detecting fentanyl in “street drugs,” but fentanyl is only one of many harmful substances and adulterants found in the supply of non-prescription drugs.

One program that provides a more detailed chemical analysis of drug samples is the Street Drug Analysis Lab (SDAL), a public service housed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Funded partly by the state allocation of opioid settlement funds, SDAL provides analytical chemistry services and information for public health.

SDAL offers mail-in, laboratory-based drug checking to communities across the state. This provides one mechanism for harm reduction stakeholders and people at risk of overdose to monitor changes in the street drug supply. Registered programs (harm reduction organizations, public health departments, and others) may send in samples on behalf of program participants, typically a few granules dissolved in a solution that renders the drug inert. Using a process called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS), SDAL’s chemists can determine the composition of drug samples—the exact molecules contained within—and share this information with the organization and individual in a HIPAA-compliant manner. Drug checking helps people understand what they are consuming and make informed decisions about their substance use. While SDAL’s services are available at a low cost to eligible organizations across the country, North Carolina-based organizations can participate in the drug checking program for free.

In addition to being an evidence-based intervention that promotes behavior change and reduces mortality,18 drug checking data can also be used to inform policy and harm reduction priorities. SDAL regularly analyzes anonymized sample data to stay abreast of emerging trends in the supply and shares these data with communities in real time. All data are available to view at SDAL’s website,19 including anonymized individual samples and aggregated results in easy-to-digest dashboards and watch lists.

Since July 2022, SDAL has analyzed 1524 North Carolina drug samples received from 42 programs across 55 counties. These samples contained 181 unique substances, ranging from common opioids to inert cutting agents to veterinary tranquilizers and industrial plastics (Table 1). On average, a sample contains 3.9 different substances. Alarmingly, in 1 out of 4 cases, the sample does not contain the drug that the sample donor expected.

Drug checking is a vital component of overdose response efforts as the drug supply becomes increasingly complex, with newer, more potent opioids and potentially dangerous adulterants posing grave risks to health.20,21 With the support of state opioid settlement funds, SDAL has grown into one of the leading drug checking labs in the country and an essential resource for educating North Carolinians and helping prevent overdose.

Looking Toward 2030

At this point, the overdose death rate in North Carolina has sharply declined from its peak in 2023. Current 2024 estimates project an overdose rate of 29.7 overdoses per 100,000 residents, representing over 1000 fewer overdose deaths relative to 2024, and outpacing the national average.5 While still short of the HNC 2030 goal of decreasing drug overdose deaths from 20.4 to 18.0 overdoses per 100,000 residents, tactical investments alongside tireless advocacy have begun to turn the curve, and we remain hopeful that this decline will continue.

However, North Carolina families are still losing too many loved ones to drug overdose. Fundamental to continuing North Carolina’s progress are timely local actions supported by local data. The opioid settlements provide one avenue for increased financial resources to reduce overdose deaths and improve public health. However, recent federal and state budget cuts could undermine progress and create local barriers to care.22 These additional budgetary restrictions may require local governments to rely more heavily on their opioid settlement funding to continue programming previously funded by the government, limiting the ability to supplement and expand opioid remediation offerings and reducing the overall impact of the funds.23 While solutions exist to save lives, they will not be as successfully implemented in North Carolina if national and state funding is restricted.

At a time of heightened scrutiny over publicly funded expenditures, both CORE-NC and SDAL are examples of programs that build and maintain community trust by upholding high standards for transparency and accountability. Both programs are tangible examples of our commitment to ensuring that all people in North Carolina are healthy and have connections to support and services within a culture of care.

Acknowledgments

CORE-NC Activities are supported by an award from North Carolina Collaboratory using Opioid Abatement Funds, as authorized under NCGA Session Law 2023-134, Section 9G.8.(b), with additional support from the Duke Energy Foundation and the Governor’s Institute.

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest beyond their roles at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center.

Correspondence

Address correspondence to Cecilia Gonzales, UNC Injury Prevention Research Center, 725 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd, CB #7505, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7505 (cgonzale@email.unc.edu).