Growth in the Older Adult Population

Every state in the United States is seeing an increase in its population aged 65 and older. This is driven by the aging of the baby boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964), increased longevity, and declining birth rates. In North Carolina, 1 in 5 of our state’s residents is aged 65 and older, ranking us 9th nationally for those in this age category.1 Over the next 25 years, those aged 65 and older will increase by 47%, from 2.04 million people to 3 million people.2 This growth is fueled not only by an increase in current older residents, but also by the fact that approximately 50,000 people aged 60 and older are migrating to North Carolina each year from other states or abroad.3 Currently, 88 North Carolina counties have more people aged 60 and older than under the age of 18.2

Increase In Need and Demand for Home- and Community-Based Services

The segment of the older adult population in North Carolina experiencing the fastest growth rate is the 85+ age group. It will grow from over 186,000 persons this year to 510,000 in 2050, a 174% increase.2 This age bracket often faces chronic health challenges and mobility limitations, driving demand for long-term services—from in-home care to skilled nursing, including home- and community-based services (HCBS). Also impacting this demand is the fact that most older adults want to age in place. According to AARP’s National 2024 Home and Community Preference Survey, 75% of adults aged 50 and older wish to remain in their current homes as they age, and 73% hope to stay in their communities.4

With added focus on HCBS, there is a corresponding increase in the role of Medicaid, which is the primary payer for these services, not only for persons aged 65 and older but also for persons with cognitive, physical, and mental health disabilities and chronic illnesses. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a non-profit organization that focuses on national health issues, estimates that based on annual National Health Expenditure data from 2022, the United States spent over $284 billion on HCBS for persons aged 65 and older and for those younger than 65 with a disability.5 Of this amount, $196 billion came from Medicaid funding, $64 billion was from other payers, and $23 billion was paid out-of-pocket.6 In North Carolina, other payers include the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and funding through a Home and Community Care Block Grant administered by the North Carolina Division of Aging.

Overview of Home- and Community-Based Services in North Carolina Medicaid

North Carolina’s Medicaid-funded HCBS are delivered through both traditional fee-for-service (FFS) State Plan services and multiple waiver programs tailored for the higher-need populations. Service recipients include those over the age of 65, as well as individuals younger than 65 who are disabled. Our focus in this article is on the role of HCBS for older adults. It is important to recognize that many older adults are dually eligible, having coverage with both Medicare and Medicaid. Those dually eligible are excluded from Medicaid Managed Care.

Many services are considered optional under Medicaid, meaning federal laws allow states to choose whether to provide them. HCBS helps older adults remain at home by offering support such as personal care, skilled nursing, specialized therapies, adult day health, respite care, home modifications, meal preparation and delivery, and even symptom and pain management at end of life. Eligibility and available services vary by program. Some options allow consumer-directed care, giving individuals the flexibility to hire and manage their own caregivers, but this may add complexity for families navigating the system.

While HCBS aims to improve quality of life and reduce costs, older adults still face significant barriers. Programs like the Community Alternatives Program for Disabled Adults (CAP-DA) Waiver have long waitlists—CAP-DA reports 3867 people waiting for slots in October 2025, as reported in the Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) Dashboard maintained by the state Medicaid agency.7 The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which provides comprehensive medical and non-medical support, operated in 2024 in 38 of North Carolina’s 100 counties, leaving many older adults without access to this cost-effective option. These gaps can lead to unmet needs, caregiver strain, and premature admission to out-of-home placement.6 Figure 1 shows five of the key HCBS for Medicaid-eligible older adults in North Carolina.8

Benefits and Cost Effectiveness of Quality Care in the Home

North Carolina Medicaid HCBS for persons aged 65 and older include short-term post-acute care under home health, end-of-life care under hospice, and ongoing support for chronic conditions through programs like Personal Care Services (PCS), CAP-DA, and PACE. CAP-DA and PACE are diversion programs that help older adults avoid nursing home placement by providing personal care and support at a lower cost to the state.

HCBS foster continuity of care, which is vital for managing chronic conditions. In-home support helps reduce the frequency of hospital readmissions and aids in maintaining or improving patients’ functional status, allowing them to perform daily activities like bathing, dressing, and mobility more effectively. Receiving care in a familiar home environment promotes dignity and a sense of independence. It also facilitates greater social engagement. For family caregivers, professional care can help mitigate stress and enables many to remain in the workforce. However, without adequate support and respite, there is a risk that family caregiver burden will rise.

The economic and social benefits of HCBS are many. Delaying out-of-home placement saves limited state resources and eases pressure on acute care systems by reducing avoidable admissions. Additionally, as a major source of employment, direct care jobs stimulate local economies by supporting both workforce development and community stability. While these benefits are clear, delivering HCBS presents significant challenges.

Challenges in Delivering HCBS

North Carolina faces significant challenges in sustaining HCBS access. Providers are grappling with severe workforce shortages, complex regulatory requirements, and increasing reliance on unpaid family caregivers to fill critical gaps. These pressures make it harder for people to get the support they need to live safely and independently at home.

1. Workforce Shortages

Recent data from the NC Center on the Workforce for Health found that roughly 1 in 8 certified nursing assistant (CNAs) positions in LTSS (a settings category inclusive of HCBS) are unfilled.9 If that seems low, it is likely because turnover rates create a nearly constant demand for more nursing assistants. This same survey found that the CNA churn rate in LTSS is 178%.9 That means if an employer starts the year with 10 CNAs, they can statistically anticipate onboarding 18 new CNAs as positions turn over throughout the year. In some parts of the state, the churn rate exceeds 200%.9 Figure 2 shows churn rates by CAN setting type.

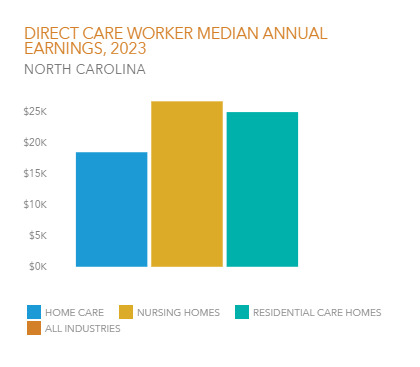

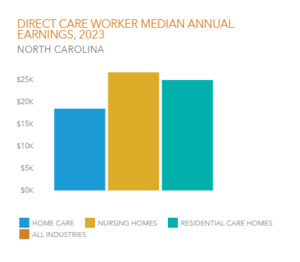

These jobs are difficult, and low pay can mean even modest incentives can draw someone away from an employer or the field altogether. In a resource-constrained environment, significantly high turnover presents an expensive challenge for employers and places a strain on the care infrastructure. Direct care workers operate with high-stake responsibilities, providing essential care to our most vulnerable citizens. Yet, median pay is $16.31 per hour with significant variance by role and setting.10 Median personal earnings in home care are 31% less than in nursing homes and 26% less than in residential care homes (Figure 3).10

One in 5 home care workers is a Medicaid beneficiary.10 Cuts in benefits could have a compounding impact on these essential workers, potentially affecting both wages, employment status, and their own access to care.

2. Regulatory and Administrative Requirements

HCBS is a highly regulated industry. Managed care, which is increasing as a service delivery method, adds complexity with varying standards across multiple plans. These costs are absorbed within Medicaid’s fixed rates, leaving little room for competitive wages for the direct care workforce. Smaller and rural providers are hit hardest, limiting access and deepening workforce shortages. Further, the uncertainty in federal Medicaid funding, such as the changes in the 119th Congress’ House Resolution 1, could make matters worse, as HCBS—an optional Medicaid service—may face reductions. This could intensify existing pressures by indirectly leading to service reductions and added barriers.

3. Family Caregiver Implications

Family caregivers are the backbone of community-based care, yet they face mounting financial, emotional, and logistical challenges that threaten their well-being and the stability of the care system. Family members are thrust into the caregiving role often with little or no training or support because they have no option other than to close the gap.

Recent data from the Caregiving in the US 2025 report underscore the strain on North Carolina’s 2.3 million family caregivers.11 Over half report negative financial impacts, with 27% taking on more debt and 22% unable to pay bills on time. Nearly 30% live in households earning less than $50,000, 40% reside in rural areas, and 15% lack insurance. Caregivers often perform complex medical tasks traditionally handled by professionals, yet more than 30% struggle to access essential home support services such as meals, transportation, and health care.

Information from local agencies such as Duke Home Health illustrates the critical imbalance between professional and family caregiving. Given coverage requirements and reimbursement limitations, Duke Home Health notes that clinicians are present in the homes of people they serve only an average of 2%–3% of the total hours of the time patients reside at home, leaving family caregivers responsible for more than 97% of the hands-on support. This reality is not unique to Duke; it mirrors patterns across the state and nationally. While professional visits are limited to care by the provider, most daily needs are met by family members. This underscores the urgent need for robust caregiver support policies and expanded access to HCBS.

Next Steps – Building for the Future

HBCS are essential to promoting the health, well-being, and independence of older adults by enabling care in the most integrated, cost-effective setting—home. Yet North Carolina’s HCBS system faces mounting strain from workforce shortages, administrative burdens, and caregiver burnout. These challenges lead to service delays, reduced availability, and increased out-of-home placements, undermining HCBS goals.

As a state, now is the time to examine how we can build on and strengthen our system of services and supports for the growing numbers of older adults in North Carolina, including Medicaid funded HCBS. Much is at stake, and it is important that elected officials, policymakers, and other stakeholders work together to implement creative solutions to address these challenges, including identifying financial and administrative barriers to service deliveries, and designing and implementing creative ways to address needs.

Key Considerations

Investing in the direct care workforce. Competitive wages, career pathways, and better workforce data can stabilize staffing and improve continuity of care.

Streamlining processes. Reducing administrative barriers allows providers to focus on supporting older adults.

Expanding family caregiver supports. Respite programs, training, family-friendly leave policies, and resources ease strain on families and sustain their ability to provide care.

Safeguarding Medicaid funding. Protecting the HCBS funding and federal match ensures long-term program viability.

Medicaid, the largest HCBS funder, plays a critical role in meeting the needs of North Carolina’s rapidly growing aging population. While we tackle big issues such as these, we also need to look at what incremental steps can be taken in the short term to enhance existing programs, such as removing the slot limit for CAP-DA and looking at policies that would equalize how the patient monthly liability is calculated for Medicaid service eligibility.

These challenges are significant. Many are identified as a priority in North Carolina’s Multisector Plan on Aging, a roadmap for meeting the needs of older adults over the next decade. This will not be an easy task, but by committing to starting the conversation now, the state can build a sustainable HCBS system that promotes independence, reduces costs, and improves quality of life for older adults and their families.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

.png)

__churn_rate_by_setting_type.png)

.png)

__churn_rate_by_setting_type.png)