Introduction

North Carolinians are living longer, feeling younger, and many are healthier than their parents and grandparents were at the same age. Many are more active and remain more engaged and productive into their later years.

So, what does successful aging really mean? Most of us want to be independent, active, and engaged in community life while requiring few health care services and caregiving supports. The foundation for this issue of the North Carolina Medical Journal (NCMJ) is the North Carolina Institute of Medicine’s (NCIOM) 2022–2023 Task Force on Healthy Aging and its work to identify policies and practices to make North Carolina a great place to grow older. The task force chose to focus on four areas key to aging in the community: falls prevention; mobility and transportation; food and nutrition security; and social connectivity. Readers of this journal will also learn more about other factors and issues that can influence one’s ability to age well, such as housing, financial security, and need for long-term care.

In 2008, the NCMJ focused its September issue on Healthy Aging in North Carolina.1 It was an important topic at the time that is even more vital today. In this issue (15 years later), authors with a broad spectrum of perspectives highlight challenges, behaviors, and the community infrastructure needed for North Carolinians to live healthier, longer, and more productive lives. These ideas and findings can also shine a light on how individuals, caregivers, and the state as a whole can address the fiscal impact of providing services for the most vulnerable. While certain subgroups of older adults may be more challenged in their efforts to achieve healthy aging, all seniors can benefit from many of the policies, programs, and practices discussed by the authors in this issue. Frailties and risks can accompany aging regardless of circumstance; falls prevention, sound nutrition, digital access, avoidance of scams, safe navigation, and social connections are some of the factors important to all.

Preparing for an Older Population

State leaders have long known that our population is aging and have undertaken many efforts since the 1970s to address the needs and opportunities presented by this demographic shift. This is documented in a timeline prepared for the Age My Way NC Summit held in October 2022.2

In presenting their view of a roadmap for healthy aging in the NCMJ back in 2008, coauthors Dennis Streets, Leah Devlin, and Tiffany E. Shubert cited then-current aging demographics and advised that, “If appropriate programs and services are not undertaken now, these numbers will dramatically increase and the demands on services and providers will be overwhelming and costly. There will also be a significant lost opportunity to realize the economic and social value of an active and healthy older population”.3

According to Swarna Reddy and Divya Venkataganesan, planners and evaluators at the North Carolina Division of Aging and Adult Services, in 2020, the number of older adults (aged 60+) exceeded younger people (aged 17 and under) in 85 of our state’s counties.4 The call for “all hands on deck” to address the “older adult perfect storm” is clear and compelling. It is projected that by 2030, 90 counties in our state will have more older residents than young; in the next two decades, the older population is expected to continue to grow by over 50%.4

Importance of Social Connectivity

In choosing to convene the Task Force on Healthy Aging, the NCIOM acknowledged the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults and the importance of supporting their capacity to safely function in their communities. Multiple challenges became very apparent with the pandemic—especially social isolation, and the digital divide.

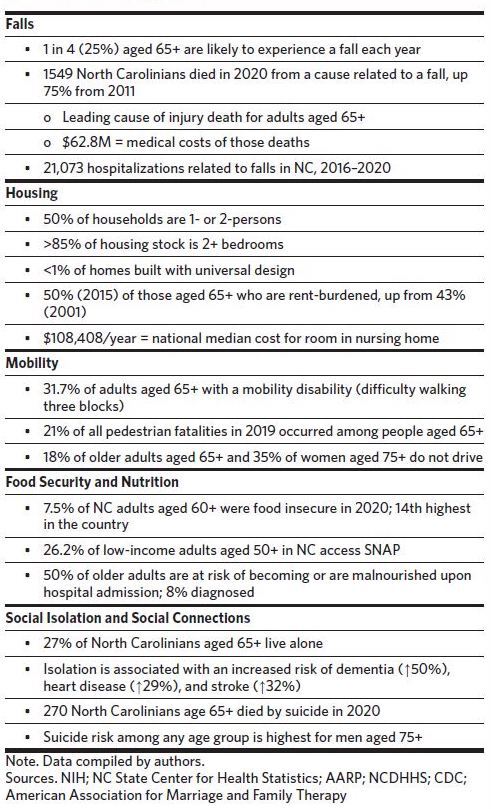

North Carolina Division of Aging and Adult Services Consumer Affairs/Legislative Liaison Program Manager Rebecca Freeman speaks to the importance of social connections in her article in this issue. She shares the research finding that social isolation has a negative impact on an individual’s mortality, similar to that of smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise, much like the impact of smoking 15 cigarettes per day.5 People who are lonely and socially isolated are more likely to have health problems, which can have serious financial implications. According to a 2018 study by the AARP Foundation, social isolation among midlife and older adults is associated with an estimated $6.7 billion in additional Medicare spending annually.6

In his article, Zachary White of Queens University of Charlotte addresses the idea that aging adults are increasingly seeking to engage online, but the consequence of “the (in)visible impact of inequitable participation” is significant.7 He notes that “social exclusion from digital equity doesn’t just intensify social exclusion. It impacts health and wellbeing—especially for older adults”.7 White finds that those who need access to people, information, and resources are often least likely to have necessary equipment, reliable and affordable internet, and digital literacy skills.7 More work is indeed needed here. The imperative is illustrated by AT&T’s recent decision to eliminate access to directory assistance via 411, calling for customers to instead use online directories.8 Pointing to areas of help, Freeman identifies North Carolina senior centers as a strength upon which people can build, as long as they are provided adequate support.5 She also highlights other initiatives designed to address social isolation, loneliness, and suicide.

Addressing social isolation is especially important when considering the resulting impact on mental health and suicide statistics. Loneliness is at the top of the list of causes of suicide among older adults, and older adults are disproportionately highly represented in suicide deaths.9 When it comes to suicide, of particular concern is suicide among veterans, where rates are 1.5 times higher than in the general population.10 David Sevier of The Generations Study Group highlights the concern about suicide, especially among older men, calling for more targeted research and greater emphasis on mental health care for veterans and their families.11

Housing and Transportation to Support Aging in Place

Most people (80%) want to stay in their homes and communities as they age.12 Using more than 50 national sources of data in seven categories (housing, neighborhood, transportation, environment, engagement, health, opportunity), the AARP Livability Index scores a community’s abilities to meet current and future needs of all residents. The easy-to-use tool can be accessed at liveabilityindex.aarp. org. Not surprisingly, housing and transportation are key aspects of livability and the ability to age-in-place.

Addressing housing issues for older adults as “a quiet crisis,” Richard Duncan of the RL Mace Universal Design Institute points to the frequent mismatch between people’s needs and the homes in which they live. Using stairs as an example, Duncan notes that “as we grow older, external stairs can become dangerous… even preventing us from leaving our homes without assistance… while interior stairs can make parts of our home unreachable”.13 Building new homes with universal design can invariably add cost, but often can be more cost-effective than retrofitting.14 Duncan makes a compelling case for planning and incentivizing age-friendly construction. At the same time, there is a need for better outreach around do-it-yourself programs and funding resources (for lower-income individuals) that can educate homeowners to retrofit their own homes to support safer aging in place.

Beyond safe, accessible, affordable housing, a key component of autonomy in aging is mobility. Mobility “disability,” defined as difficulty walking three blocks, affects nearly one-third of adults aged 65 and older (Table 1). This decreased mobility can lead to dramatically increased risk of falls and injury, unsafe reliance on personal vehicles, social isolation,and decreased access to needed services. Safe and accessible public transit systems can facilitate access to needed services, enhance independence, and eliminate dependence on driving if it becomes less safe with the sensory, reaction time, and cognitive declines that can accompany aging.

In an interview in this issue, Ryan Brumfield of the North Carolina Department of Transportation acknowledges the challenges of serving an older population. From his perspective with DOT’s Integrated Mobility Division, Brumfield sees people outliving their ability to safely drive by up to 10 years.15 Brumfield also suggests an increasing need for access to efficient, reliable, and affordable transportation, pointing to DOT’s “Complete Streets” program, which looks at safe infrastructure for all modes, including walking and biking. He Initiatives such as integrated mobility, on-demand mobility, and mobility as a service16 can offer means to address this challenge.

Trips, Falls, and the Connection to Safe Housing

While having access to affordable and reliable transportation becomes increasingly vital for mobility as one ages, so too is a safe environment in the home and community. Ellen Schneider of the UNC Center for Aging and Health, who wrote about this in her 2008 NCMJ article, once again emphasizes this factor in her 2023 article—coauthored with Ellen Bailey and Ingrid Bou-Saada of the North Carolina Falls Prevention Coalition. They note that “falls are one of the most common and significant health issues facing persons aged 65 years and older”.17 It is encouraging that the NC Falls Prevention Coalition, established in 2008, is still doing great work to promote falls prevention education and evidence-based programming, appropriate screening and referrals, and increased awareness and action vis-à-vis this public health issue.

Relatedly, Cheryl Brandberg in her article provides an excellent illustration from a Community Housing Solutions of Guilford, Inc. demonstration project. The project included age-in-place (accessibility) home modifications combined with visits by nurses and occupational therapists to improve physical mobility. This demonstration project led to a remarkable improvement in safety with a decrease in falls by 80% in addition to improving activities of daily living, quality of life, and mental health.18

Food and Nutrition Security

As with many other issues, the COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted the existing food insecurity crisis in America. Those who are food insecure lack reliable access to sufficient, affordable, nutritious food. In 2020 alone, more than 9 million older adults in the United States lacked consistent access to enough food.19 The lingering impacts of the pandemic, along with rising inflation and the increasing cost of basic necessities, have been driving spikes of food insecurity rates among certain groups, including older Black, Hispanic, and rural households—further contributing to existing disparities.20 Communities without access to healthy foods, known as food deserts, are less “livable” and make it more difficult for healthy aging in place.

Nutritious food is vital for prevention or management of chronic diseases and maintenance of muscle mass, and thus healthy aging. Older adults who are food insecure are more likely than their food-secure counterparts to have limitations on activities of daily living, have conditions like diabetes and depression, and experience heart attacks.21 Audrey Edmisten of the North Carolina Division of Aging and Adult Services provides a deeper dive into North Carolina’s food insecurity, malnutrition, and the impact on health and physical well-being in her article in this issue.21 While rates of food insecurity are high, participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) among eligible older adults is low, despite the program’s benefits. A 2022 AARP report estimates that 16 million—or over 60% of—eligible adults aged 50 and older in the United States were not enrolled in the program in FY 2018.22 Removing barriers, expanding program eligibility, simplifying the application process, and implementing innovative program processes can help improve participation and access rates and ensure those who need help the most are able to access it.

Financial Security

According to a Pew survey, factors that predict happiness are good health, good friends, and financial security.23 Many of the multifaceted variables that can influence healthy aging require financial resources, such as a safe and accessible home, nutritious food, internet access, and an automobile or alternate transportation to access daily living activities and social interaction. The NCIOM task force has identified the need to protect older adults’ financial resources from fraud and exploitation and to increase access to supportive programs (like the aforementioned SNAP) that can help people with lower incomes stretch their finances.

Many aging North Carolinians will want or need to continue to work longer than previous generations. However, some are forced into early retirement through job losses or due to health issues, providing care to a loved one, or other reasons. Some are underemployed, taking lower-paying jobs, or are only able to find part-time work. Policies and programs to help keep more older adults actively and productively contributing will help with our workforce shortages while at the same time strengthening financial security.

Another approach is to increase retirement savings. Through his overview of retirement security in this issue, AARP State Director Mike Olender shares that with only Social Security and minimal savings, many will lack sufficient income for basic necessities.24 He identifies the lack of payroll deduction as a barrier for small business employees who want to save for retirement. Those who have a portion of their paycheck automatically deducted for retirement savings are 20 times more likely to save, yet roughly 1.7 million small business employees in North Carolina have no workplace retirement savings opportunity.24 Olender notes that other states have set up public-private programs so that small businesses can offer this benefit and suggests this change in North Carolina.

Long-Term-Care Services to Support Aging-in-Place

In the sidebar in this issue by Sabrena Lea of NC Medicaid on the cost and challenges of Medicaid-funded long-term care for the growing aging population, she highlights the continued movement from institutional care to the preferred in-home and community care.25 Noting that the workforce to deliver this care is “catastrophically insufficient,” she concludes: “Moving forward, NC Medicaid will be challenged to use its payment and policy levers to ensure that the Medicaid health care system is sustainably funded to ensure the availability of an appropriately prepared workforce to deliver quality services and supports”.25

Turning to unpaid family caregivers—often called the backbone of long-term care—we see that North Carolina has an estimated 1.3 million family or informal caregivers (accounting for 1.1 billion care hours, or $13.1 billion annually).26 Many sacrifice their own physical and mental health, their relationships and jobs, and experience financial strain. In their article on caregiving, Erin Kent of the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and coauthors critique existing North Carolina policies and programs and offer recommendations. They advocate for an integrated approach to caregiving that takes a whole-person, whole-family perspective and offers financial assistance and supports to keep caregivers participating in society.26

Disparity Challenges for Healthy Aging

It will be necessary to reframe the narrative of the aging process to acknowledge the role of social, behavioral, and environmental factors on the health and well-being of the growing older adult population. The experience of marginalized older Americans has been affected by a historical backdrop characterized by structural racism, ageism, sexism, and other prejudices and inequities that influence one’s social positioning.27,28 Understanding the daily lived experiences of these groups allows for the acknowledgment of the impact of social drivers of health on older adults’ well-being, while also acknowledging the power of resilience and strength. This shift in focus, however, cannot be the responsibility of one person, community, or institution, but of all those willing to serve as “change agents” in improving the health and care needs of all North Carolinians.

A stronger focus on the influence of social determinants of health on the well-being of older adults allows us to not only better understand the “how” but also the “why” of inequities that persist throughout the life course in marginalized communities. Disparities in access to resources are challenges older adults can face as they strive to age well. This is a reality that the NCIOM Task Force on Healthy Aging has considered and prioritized throughout its deliberations.

Next Steps

The Task Force on Healthy Aging met throughout 2022 and continues into 2023. It addresses many issues that are explored in substantial depth, with a final report scheduled for later in 2023 that will include actionable recommendations as well as those that may require further study and resources to ensure their full effect.

The task force has looked to the collaborative Age My Way initiative to help spark state-level action (with broad stakeholder involvement) to assist with some of its work. This partnership between the State of North Carolina and AARP NC was developed to help identify priorities for making our neighborhoods, towns, cities, and rural areas great places for people of all ages. Central to the initiative was a statewide survey of people aged 45 and older to identify priorities, such as safe and walkable streets; age-friendly housing and transportation options; access to needed services; and opportunities for residents of all ages to participate in community life.29 In Fall 2022, preliminary findings were shared at the aforementioned Age My Way NC Summit, which brought together stakeholders from across the state to discuss survey results and renew the call for “all hands on deck” to better prepare for the growing aging population. The survey’s key findings confirmed that people want to stay in their communities as they age; they also want to age in their own homes and remain independent. Individuals worry about what will happen when they are no longer able to drive, and about becoming socially isolated. Employment for older and disabled adults is an important issue that must also be addressed moving forward. More information about the survey and the summit presentations can be found at https://hometownstrong.nc.gov/age-my-way-nc.

We cannot continue to just plan for the future when the aging imperative is here and demands a meaningful response now. With so much dependent upon what we can do formally through policy, programs, education, and research, we must also recognize the essential role we each have in ensuring our own well-being. This shared responsibility is necessary in order for all older adults to realize healthy aging.

The articles in this issue of the journal serve as a springboard for serious consideration, and ultimately implementation, of the recommendations of the NCIOM Task Force on Healthy Aging. Urgent action is essential if we are to see our growing older population enjoy good health and independent, productive living in the community.

Author Bios

Lisa Riegel, MS manager, Advocacy & Livable Communities, AARP North Carolina, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Tamara Baker, PhD, MA professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Dennis Streets, MPH, MAT retired director, North Carolina Division of Aging and Adult Services and executive director, Chatham County Council on Aging, Pittsboro, North Carolina.

Disclosure of interests

T.B. and D.S. are serving as co-chairs of the Task Force on Healthy Aging; L.R. serves as a steering committee member for the task force. No further interests were disclosed.