Introduction

In November of 2022, North Carolina released a white paper titled, “Keeping Families and Communities Safe: Public Health Approaches to Reduce Violence and Firearm Misuse Leading to Injury and Death”.1 The white paper lays out a public health framework for addressing firearm violence and a series of steps that can be taken to reduce firearm-related violence, injury, and death. This commentary further lays out the impetus for and context of that paper, summarizes the content, and identifies actions taken since its publication and next steps.

Why Now?

Nationwide and in North Carolina, firearm violence, injury, and death have been escalating. According to data from the North Carolina Violent Death Reporting System (NC VDRS), five North Carolinians die every day from a firearm-related death and more than 1600 people in North Carolina died from firearm-related deaths in 2020.2 In the past 10 years, more than 62% of all violent deaths in North Carolina were firearm related, and firearm deaths increased by 36%.2

In recent years, we’ve also seen many North Carolinians purchasing guns for the first time, with the number of gun permits issued more than doubling during calendar year 2020, according to unpublished data from local sheriffs’ offices. Community violence is increasing, especially in our communities of color, low-wealth areas, and rural regions. Nearly half of all firearm-related homicides of women are a result of intimate partner violence, and almost 60% of intimate partner homicides involve a firearm.2 Firearm suicides also are increasing, and now more than half of firearm-related deaths are suicides.

As described in the 2023 Annual Report of the North Carolina Child Fatality Task Force (NC CFTF), firearms are now the leading cause of child injury death and are increasing. From 2012 to 2021, over 600 North Carolina children died from a firearm-related injury, including 121 North Carolina children in 2021.3 Child deaths in North Carolina due to firearm injury skyrocketed in 2020 and 2021, with a 231% increase; among youth, more than 50% of suicides and 80% of homicides in 2021 involved a firearm.3

In the past four years, juvenile offenses involving firearms have grown from 4% to 13% of all juvenile crime, with an increase from 1000 annually to more than 4000 annually.1 Juveniles are most often gaining access to these firearms from their own homes or stealing them from unlocked vehicles. According to unpublished data from the Division of Juvenile Justice, 20% of all car break-ins committed by juveniles last year were for the purpose of stealing a firearm. This is double the rate from just three years earlier (Department of Public Safety, Division of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Research request RE-738, “Firearms Research Brief.” May 2022).

In the context of this ongoing, everyday firearm violence, North Carolina also became the site of a mass shooting event.4 A few days later, a toddler climbed into the back seat of his father’s truck, found a gun, and killed himself.5 Unlike in other tragedies when people come together to find solutions, people remained divided in their stances on how we should respond to firearm-related deaths. As leaders, we knew we needed to try to take a different approach; we needed to find a way forward together.

Firearm violence, misuse, injury, and death are many distinct problems, and there is not just one answer, there are many. There is another, less-discussed reality: that there are areas of consensus in which we can agree. Everyone wants to feel safe. We all want to keep our families and communities out of harm’s way, but almost 40% of Americans feel less safe than they did five years ago.6 We can protect people’s Second Amendment rights and also keep people safe. In fact, we have to, in order to make progress together on this critical issue. We need to identify and build on those areas of consensus with common-sense strategies and implement a layered approach to these problems. That is the public health approach that has been successful with many issues in the past; it is a similar strategy to that used to address motor vehicle injuries and deaths, for example. We did not take away people’s cars or their right to drive, but we layered multiple prevention strategies that reduced risk, injury, and death by increasing the safety of the environment, the vehicle, and the driver.

Developing a Public Health Approach to Preventing Firearm Deaths

As we conceived the content of the white paper, we started with the evidence and leveraged policy work done by other organizations across the nation. For example, we drew from the American Public Health Association’s document on evidence-based interventions and policies; the Association of State and Territorial Health Officer’s Policy Statement on Preventing Firearm Misuse, Injury, and Death7; Safe States Policy Recommendations to Prevent Firearm Related Injuries and Violence8; and the RAND synthesis of the Science of Gun Policy.9

We knew that robust work had already been done on firearm violence across state and local agencies and governments, law enforcement, public health, health care, educators, and communities here in North Carolina. We identified examples of this work. Governor Roy Cooper and the Department of Public Safety convened several roundtables with law enforcement professionals. To complement those discussion, Governor Cooper also convened a roundtable that included health, public health, education, and community organizations along with law enforcement to further inform the work of addressing firearm violence as a public health issue as well as a public safety one. These discussions raised awareness that many sectors were working to address firearm violence, but their work was siloed. As one law enforcement officer said at the health roundtable: “I had no idea health people were working on this issue.”

The content and recommendations in the white paper were informed by the evidence, work and recommendations from other organizations, existing activities in North Carolina, and the roundtable discussions. The recommendations seek to find areas of consensus, advance collaborative work, and take a pragmatic approach as to what is possible.

What’s in the White Paper

Key to addressing firearm violence as a public health issue is using a public health framework with four key steps (Figure 1):

1. Define and Monitor the Problem

Three systems reveal when and where firearm deaths and injuries happen and can identify unequal impact in groups of people and communities. North Carolina collects data on emergency department visits via the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool (NC DETECT). Non-fatal firearm-related injuries are tracked via North Carolina Firearm-Related Injury Surveillance Through Emergency Rooms (NC-FASTER). Violent deaths are monitored through the North Carolina Violent Death Reporting System (NC-VDRS). These data help NCDHHS and our partners see trends, guide priorities, understand risk factors, and develop and evaluate targeted prevention strategies.

2. Identify Protective and Risk Factors

Certain populations experience higher rates of firearm injury and death than others. Black North Carolinians are almost twice as likely as White North Carolinians to be killed by a gun.10 The veteran suicide rate in North Carolina was 250% higher than that of the general population from 2016 to 2020; for those aged 18 to 34, it was 610% higher than that of the general population.11 The use of firearms as a method of suicide among veterans is 73.8%, compared to 53.6% for non-veterans.12 Rural and economically vulnerable communities experience higher rates of firearm violence. Firearms are now the leading cause of child injury death in North Carolina.13,14

Ready access to firearms increases the risk of violence, including firearm violence; 42% of North Carolina adults have a firearm in or around the home, and over half of firearms that are stored loaded are also unlocked.14 A lack of safe storage of these firearms by adults allows youth access to these weapons The 2021 North Carolina Youth Risk Behavioral Survey showed that 30% of North Carolina high school students reported it would take them less than an hour to get and be ready to fire a loaded gun without a parent or other adult’s permission; for White males, it was 40%.14 Other risk factors include mental illness; however, people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of firearm violence than perpetrators.15 Substance use disorders can increase the likelihood of violent behavior and the presence of a firearm in a domestic violence situation increases the risk of homicide by 500%.16,17

Protective factors include increased safe firearm storage and reduced access to lethal means, prevention, and support services for populations with higher risk of firearm injuries, and increased access to mental health and substance use disorder services.

3. Develop and Test Prevention Strategies

Many prevention activities are happening across North Carolina, including encouraging safe storage and reducing access to lethal means, with strategies that include local firearm safety teams, counseling on access to lethal means, firearm safe storage maps, distribution of free gun locks, veteran suicide prevention programs, and safe shooting sports programs.

Additional efforts include protection for those at the highest risk of firearm injuries or death via strategies like community and hospital violence prevention and violence interruption programs, restorative justice and re-entry programs, and protective orders that limit possession of firearms in certain domestic violence situations. The launch of the 9-8-8 mental health crisis hotline and creation of a real-time list of open behavioral health beds in facilities across the state to more quickly connect people to care may also reduce firearm-related injuries and deaths.

4. Assure Widespread Adoption

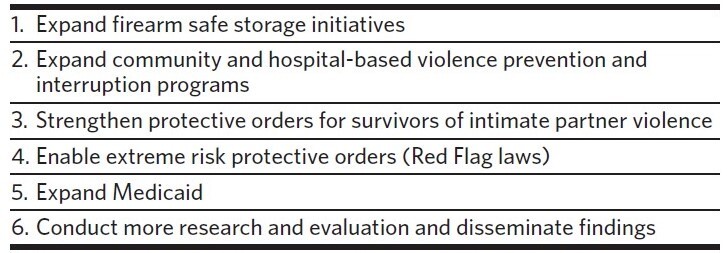

Multiple agencies and groups across North Carolina have taken steps to initiate violence prevention programs. The state is encouraging safe storage as a priority of the Child Fatality Task Force of the General Assembly; the Department of Public Safety led the creation of the statewide Action Plan for School Safety; NCDHHS has a Firearm Safety Awareness and Education webpage and launched the North Carolina Suicide Action Plan. The white paper laid out recommendations for key actions that can be taken to reduce firearm death and injury (Table 1).

Progress Made and Next Steps

Significant steps have been taken since the publication of the white paper in the fall of 2022 and more activities are being planned. Medicaid Expansion has been signed into law in North Carolina and will be implemented with the enactment of a 2023–2024 state budget.

Further federal investment is enhancing North Carolina’s work in this area. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) was signed into law on June 25, 2022.18 The United States Department of Justice has described the BSCA as, “the most significant piece of federal gun safety legislation in almost three decades”.19 The law makes historic investments in violence interruption, school safety, and mental health infrastructure.

The Governor’s Crime Commission (GCC) has prioritized hospital violence interruption programs for use of Crime Victims Fund dollars under the Victims of Crime Act.20 Additionally, the GCC is applying for funding opportunities for community-based violence intervention and prevention initiatives available through the federal BSCA. This is also an area ripe for philanthropic funding.

A statewide safe storage campaign, NC S.A.F.E. (Secure All Firearms Effectively), was launched in 2023. A vendor partner was selected, key messages were developed, traditional and social media outlets were identified, and a local planning toolkit was developed. The website ncsafe.org went live in May, followed by a week of action and community events in June. A gun storage map is included on the campaign’s website as a resource for firearm owners who wish to temporarily store firearms outside of the home. The campaign will promote safe storage practices through the creation of local firearm safety teams. Finally, the campaign will provide training resources on Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM), which addresses firearms, medications, and other lethal means.

Governor Cooper established the Office of Violence Prevention on March 14, 2023. The office will be housed within the Department of Public Safety and is working to enhance collaboration and coordination across state agencies (including NCDHHS, the Department of Justice, and GCC); improve data collection and sharing; manage grant programs and direct federal funding to communities focused on violence prevention; provide technical assistance and sharing of best practices and promote cross-agency collaboration in local communities; and partner with universities for research, data, and evaluation.

As part of this work, in partnership with the US Department of Homeland Security Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety will be leading a collaborative effort to develop and implement a targeted violence and terrorism prevention strategy at the state level.

The North Carolina Public Health Association passed a resolution declaring firearm violence a public health crisis in 2023; firearm violence was a highlighted topic at the Public Health Leaders Conference in March. This topic will be a key item at the North Carolina Public Health Association Annual Conference in September 2023, with a full day pre-conference session recognizing the 20-year anniversary of the North Carolina Violent Death Reporting System. Work is also being done to enhance judicial training to strengthen protective orders for victims of domestic violence.

We can, and must, make progress in preventing firearm-related injury and death by finding areas of consensus and using a data-driven public health approach to addressing this crisis.

Disclosure of interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.