Childhood food insecurity (FI) negatively affects developmental trajectory, cognitive performance, social-emotional well-being, and physical health, and is associated with lower rates of school readiness and poorer academic outcomes.1–6 Approximately 1 in 5 children in North Carolina lived in households experiencing FI prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This rate increased to 1 in 3 by September 2021.7,8 Black and Hispanic families are almost twice as likely to experience FI nationwide, and this disparity has worsened in the context of COVID-19.9

Due to increasing FI rates and the clear association with worse health, FI screening is increasingly incorporated into clinical care using the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended Hunger Vital Sign™, a validated two-question screening tool.10 To address positive screens, health care providers utilize various interventions, such as providing patients with a list of community resources, offering one-time food assistance through clinic-based food pantries, or assisting with resource navigation. However, such heterogeneous approaches can lead to disjointed service provision and follow-up. Implementing FI screening in clinical settings and establishing it as a quality metric mandates that we improve the strategies we use to address identified FI. Improved strategies include increasing collaboration between clinical and community sectors and acknowledging community sectors’ past and present expertise in supporting the social needs of children and families.

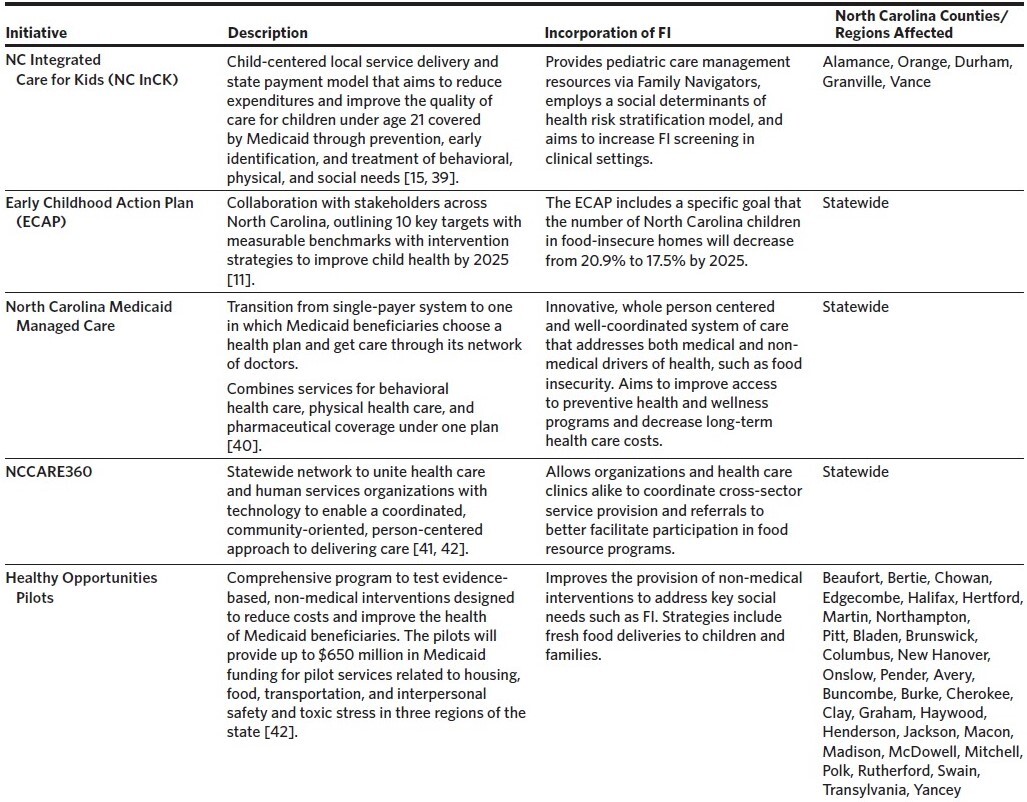

North Carolina is well positioned to support cross-sector collaboration to address childhood FI given multiple ongoing initiatives in child and public health (Table 1). In 2018, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper tasked the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) with developing a statewide plan to improve early childhood health in North Carolina by 2025. The resulting North Carolina Early Childhood Action Plan includes goals of decreasing the number of children in food-insecure homes, accelerating public-private collaboration, improving data tracking, and increasing coordination across state systems.11 Additional state and public health innovations aim to improve “whole person care” across North Carolina through addressing social needs. These include: 1) requirements for social-risk screening by payers and providers with the transition to Medicaid Managed Care in 2021; 2) NCCARE360, the first statewide coordinated care and referral network to facilitate cross-sector service provision; and 3) Healthy Opportunities Pilots, which will evaluate the systematic provision of evidence-based, non-medical interventions funded by Medicaid to address key social needs in 33 North Carolina counties (Table 1).12–14 The North Carolina Integrated Care for Kids (NC InCK) Model, an additional effort that was launched in five North Carolina counties in January 2022, is one of seven federally funded, child-focused models that aim to transform care delivery for Medicaid-insured children. NC InCK strives to improve the state’s care network through the holistic identification of clinical and non-clinical risk factors, care coordination, and alternative payment models.15

These varied initiatives have enabled the organic development of cross-sector partnerships that bridge the clinical sector’s identification of children’s social needs with the non-medical sector’s long history of meeting these needs. To further inform the design of processes within the emerging model of NC InCK that leverage such partnerships, we assessed barriers and opportunities for improving cross-sector collaborations to address childhood FI.

Methods

Participants

From December 2020 to March 2021, we conducted interviews with informants representing programs in various sectors, including community (e.g., food pantry), education (e.g., school lunch program), and government (e.g., federally funded NCDHHS public health programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]). These informants represented either statewide programs or programs operating within at least one of the five counties implementing NC InCK (Alamance, Durham, Granville, Orange, Vance). Interview participants were identified through suggestions from collaborators, online search engines, and snowball sampling.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were performed to explore existing facilitators, barriers, and strategies for addressing FI among children through cross-sector collaboration. We also assessed the impact of COVID-19 on organizations. The semi-structured interview guide included three main domains (Appendix 1): 1) programmatic approaches to engaging children and families; 2) cross-sector collaboration and data-sharing; and 3) barriers and potential solutions.

All interviews were conducted via Zoom and were audio-recorded. An online transcription service transcribed all interviews.

Analytic Approach

We used a qualitative descriptive design for our analysis, which is well-suited to research that seeks to expand upon a poorly understood phenomenon by describing the who, what, and where of individual experiences.16 Due to the timeliness of findings, we employed rapid qualitative analysis methodology.17,18 We first created a rapid analysis template for data analysis.18 Team members input field notes from interviews into the template, which were then refined after either listening to the interview recording or reading the interview transcript. All rapid analysis results were reviewed by two team members to confirm accuracy. Rapid analysis results were collated into a matrix with interviews by row and rapid analysis domains by column. Team members reviewed the matrix to identify major themes, which were then discussed and agreed upon by all team members.

Team members conducted a network analysis by collapsing similar organizations into broad organization types (e.g., community, health care) and then reviewing rapid analysis templates to identify major collaborations and referral sources. These relationships (i.e., organization types, collaborations, referrals) were then placed into Gephi, a visualization software, to create a network map.

Results

Informant and Organization Characteristics

The informants (N = 34) represented organizations based in the community (n = 21), education (n = 7), and government (n = 6) sectors. Stakeholders included a food collaborative, community program directors, school nutrition directors and social workers, and North Carolina directors of government food programs. All five NC InCK counties were represented, and five interviewees represented statewide programs. Interviews averaged 52 minutes (range 26–82 minutes).

Food Resource Networks

A network map for the programs we interviewed is included in Figure 1. Stronger collaborations and referrals occurred between the community and school sectors, while the health care sector was more peripherally involved in meeting children’s food needs. For example, informants shared that school social workers played an important role in identifying FI and served as a connection between school and community resources (n = 8). Most commonly, individuals learned about available services through word of mouth (n = 20). Two programs reported using the NCCARE360 platform, while over a third of informants were unfamiliar (n = 14).

Collaboration occurred both within and across sectors. For example, within-sector collaboration occurred at schools among school lunch staff, social workers, and nurses to connect students and families to available federal programs and supplemental food (Figure 1). Meanwhile, community-based organizations (CBOs) reported sharing resources, such as food, money, and volunteers. Some organizations (n = 6) shared data with cross-sector partners to facilitate cross-program service provision and conduct program evaluations but typically provided only aggregate data or program-monitoring metrics. Only one organization shared individual-level participant data with other CBOs. Informants described privacy regulations as a prominent barrier to individual-level data-sharing.

Collaborations also occurred across sectors, including school-based food assistance programs facilitating connection to CBOs (e.g., food pantries) and CBOs hosting bi-monthly meetings with other food programs to establish donation and distribution processes. Half of our informants (n = 17) mentioned utilizing these cross-sector partnerships to increase families’ food autonomy and access to food variety. For example, organizations reported partnering with local farmers to receive fresh produce; working with local restaurants to receive pre-made meals, hot food options, and leftover ingredients; and collaborating with grocery stores to receive gift cards, produce, and food storage appliances (e.g., refrigerators and freezers).

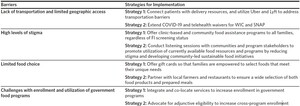

Barriers to Accessing Food Resources and Opportunities for Cross-Sector Solutions

Transportation barriers, particularly for rural areas. In 71% of our interviews, informants cited transportation as a key challenge for families facing FI (Table 3). Lack of transportation can be particularly challenging in rural communities where there is limited public transportation and poor road quality. Multiple informants (n = 8) discussed how cross-sector collaboration is necessary in order to serve hard-to-reach populations. For example, informants emphasized the importance of establishing food and donation distribution channels to reduce the burden of food delivery. Informants shared that COVID-19 and the resulting shutdown of school-based meal distribution further exacerbated existing transportation challenges. However, COVID-19-related innovations included partnerships between CBOs, Lyft, Uber Health, and coalitions of volunteer delivery drivers to drop off food products at homes (Table 2). Many hope to see such innovations extended beyond the pandemic.

Stigma. About a third of informants mentioned stigma as a barrier to accessing food resources (n = 11; Table 3). Stigma can be especially prevalent in rural communities where individuals are more likely to be identified when accessing food resources. Additionally, informants shared that some individuals experience feelings of “pride” that prevent them from registering for food programs. This phenomenon was reported as especially prevalent amongst teenagers in school systems, causing subsidized meal programs to have low levels of participation because universal free meals are not provided. To alleviate the impacts of stigma, programs (n = 9) described limiting interactions to increase privacy and avoid the possibility of personal identification. For example, many public-school programs operate weekend supplemental food assistance programs consisting of pre-stocked backpacks but no interaction with students. Other programs see personal relationship-building as key to helping clients overcome feelings of shame when seeking food resources. Informants suggested community listening sessions with individuals using food assistance programs to develop cross-sector solutions. Such collaboration could help to identify modifiable pain points, highlight the importance of community-led food initiatives, and form coalitions of diverse FI stakeholders (e.g., CBOs, school-based professionals). Additional knowledge about program details, client needs, and support initiatives could increase awareness of FI while simultaneously reducing stigma (Table 2).

Lack of food choice. Many informants described limited food and meal choices as a barrier for their participants, with 38% reporting a lack of nutritious, culturally appropriate food choices (n = 13; Table 3). Specifically, informants identified a need to increase access to fresh produce and appropriate foods for Latinx clients. Several informants reported that the ability to distribute grocery gift cards during the pandemic was well received; clients enjoyed the flexibility of choice and the gift cards helped to reduce shame (Table 2).

Challenges accessing government food programs. Informants reported that many caregivers find it challenging to enroll in government food programs despite being eligible. In particular, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) application process can be burdensome due to extensive paperwork and language barriers (Table 3). Additionally, some clients lack the transportation and/or technology needed to apply for benefits. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, enrollment required multiple in-person appointments, which were often lengthy meetings with long wait times. However, COVID-19 policy changes allowed for the remote issuance of benefits and telehealth appointments. Moreover, the pandemic electronic benefit transfer program required data-sharing agreements between NCDHHS and the North Carolina Department of Instruction to facilitate enrollment and administration of the program. Stakeholders reported that the pandemic accelerated the development of these required data-sharing agreements due to a shared goal of feeding children. They reported a desire to build upon the development of such agreements beyond the pandemic to facilitate additional innovative policies, such as adjunctive eligibility for other means-tested programs, a process by which enrollment in one federal program makes the individual automatically eligible for another federal program (Table 2).19

School nutrition stakeholders described how the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) is governed by regulations that limit access. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a congregate feeding requirement mandated that students eat at the meal distribution site and prohibited schools from putting meals on buses; waiving these requirements dramatically increased utilization of SFSP, but community stakeholders anticipate the expiration of these innovations. A number of informants (n = 4) reported that partnerships with school social workers play a crucial role in tracking children, their service utilization, and their eligibility for government programs across school districts, but that social workers were often under-resourced and had limited capacity to fulfill this role.

Discussion

We identified several barriers limiting access to current FI resources for children and explored opportunities for collaboration between CBOs, schools, health care systems, and the government to better address childhood FI in North Carolina. Consistent with prior findings, barriers to utilization of food programs included transportation challenges, stigma limiting use of available programs, lack of autonomy, and burdensome enrollment processes for government programs.20–22 However, COVID-19 accelerated the implementation of novel strategies and solutions addressing limited access to food resources. As the COVID-19 pandemic moves into an endemic phase, some of these innovations have been discontinued, possibly leading to a resurgence of many food access barriers and increasing the importance of advocacy by health care providers and community stakeholders.23,24

Similar to other studies, our work demonstrated limited collaboration between the health care system and other sectors leading efforts to address childhood FI.25 Few organizations had any interaction with health care providers, and most were unaware of initiatives to address social needs in the clinical setting. While these interviews were conducted early in the NCCARE360 implementation process, nearly all of the informants expressed interest in the platform as a means to coordinate cross-sector service provision and referrals to food resource programs. Recognizing the isolation of the clinical sector, North Carolina is well positioned to successfully bridge the health care system with community programs and public health initiatives. Innovative models, such as NC InCK; NCCARE360; and the 2018 Healthy Opportunities Pilot and associated Section 1115 waiver that provides financing for case-management services related to housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety26 provide the foundation to improve cross-sector partnerships. COVID-19 accelerated the development of health care and community partnerships that effectively meet patient food needs beyond isolated initiatives focused only within the health care setting (e.g., clinic-based food pantries or food prescription programs). These partnerships between health care and community promote innovations to address FI that harness the skills of CBOs rather than duplicating these initiatives within the health care system. Robust closed-loop referral processes connecting health care and community may help to better integrate systems without redesigning existing processes. The introduction of direct food distribution and the integration of federal food program navigation assistance into the clinical setting highlight opportunities for successful transferability of community initiatives to the health care sector.

Organizations were able to leverage pandemic innovations to meet increasing needs, and stakeholders reported multiple opportunities to expand these initiatives. Challenges with program access during the pandemic highlighted opportunities for cross-sector collaboration, such as utilizing Lyft, Uber Health, and DoorDash (Project DASH) for food deliveries or transportation to food assistance programs.28–31 The development of data-sharing agreements for the pandemic electronic benefit program and the co-location of services made accessing federal programs less challenging. Stakeholders reported plans to develop adjunctive eligibility agreements for Medicaid, WIC, and SNAP; to explore opportunities for placement of WIC enrollment kiosks in high-trafficked community locations; and to increase the utilization of telehealth in the WIC program.32 Finally, initiatives to broaden SFSP access, distribute grocery gift cards, and allow families to purchase their own meals using pandemic electronic benefit transfer money helped to increase family food autonomy and reduce stigma.

Within-sector and cross-sector partnerships between schools, communities, and government programs are cost-effective and build community trust.34 However, many of the waivers made available during the COVID-19 pandemic have been or will be discontinued when the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration ends.35 North Carolina’s existing investment in whole-person health can be leveraged to support continued development of novel cross-sector coordination and innovations while also working to advocate for continued policy solutions to address barriers reported by program leaders.36

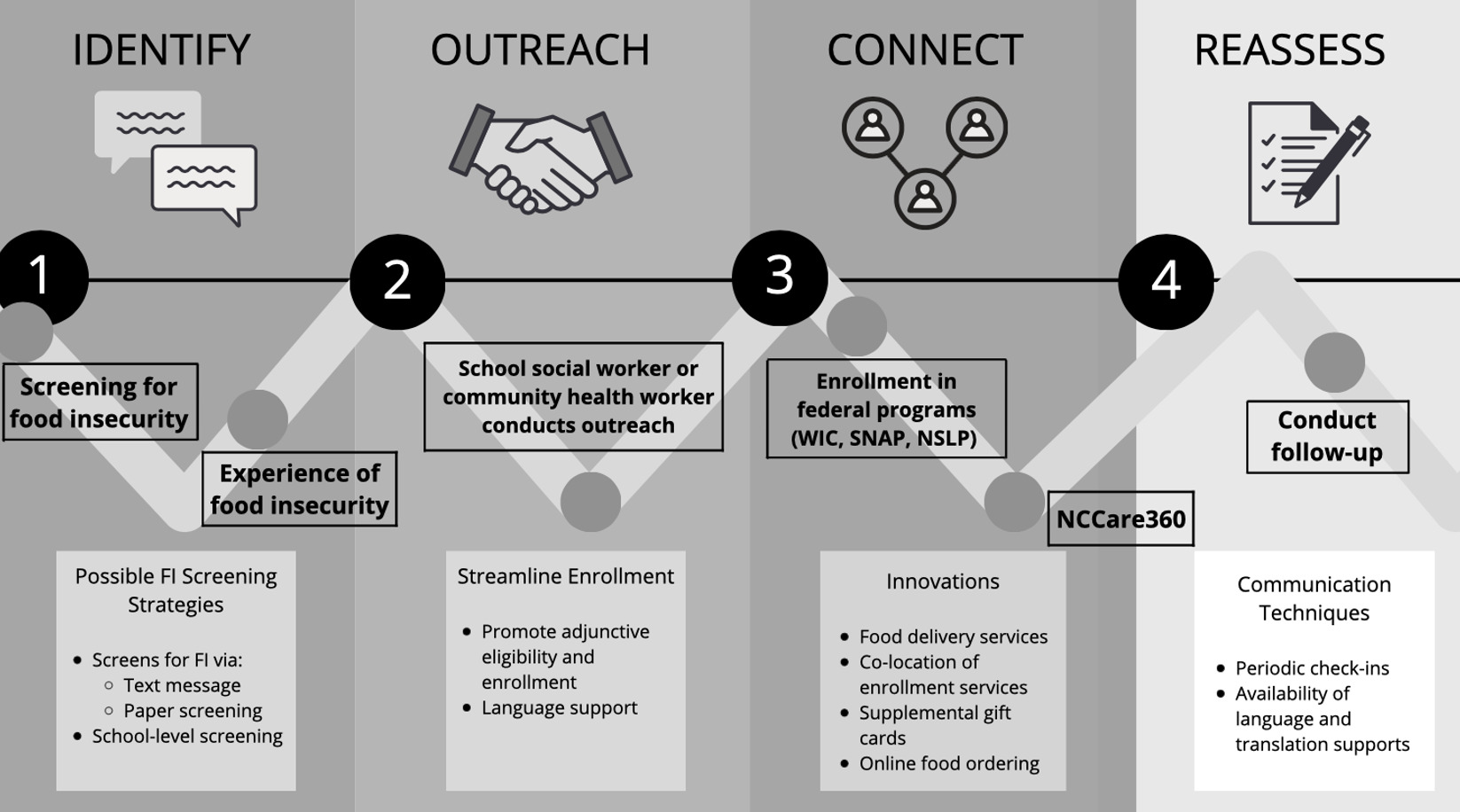

Leveraging the knowledge gained from informants, we designed a cross-sector model for NC InCK, which details how a child and family would ideally engage with resources through health care and community sectors (Figure 2). Primary care clinicians are well positioned to bridge the gap between the health care sector and existing community resources addressing FI due to frequent interaction with young children and their role as the foundation of the medical home.37 We suggest a child be screened for FI in either a health clinic or school-based setting to best leverage trusting relationships. The health care provider or educator can begin connecting the child and family to resources at both the community and state level once they are identified as experiencing FI, greatly benefiting the child. The provider or education professional should follow up with the family periodically to ensure that they are able to enroll in and access the services that fit their unique needs. The reassessment information could then be incorporated into existing electronic health record (EHR) data. This identification, outreach, and reassessment model can be incorporated into a range of initiatives that address social needs and that are incentivized in North Carolina’s transition to value-based payment models to “purchase health”.38 While this model builds upon the strengths of each sector, this “ideal” system does rely heavily on CBOs and schools to intervene. These organizations may lack the funding and personnel to meet newly identified food needs. Moving forward, stakeholders from the community and schools should be included in discussions with health care systems that are redesigning care models.

Our study had several limitations. While we included informants from the community, education, and government sectors, the majority of our informants represented the five NC InCK counties (Durham, Orange, Granville, Vance, and Alamance) while relatively few represented a statewide program. Although having representation from more counties would improve generalizability, these counties are racially and ethnically diverse and represent urban and rural communities. Second, interviews were conducted within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted the information participants shared. While some findings may not fully carry forward into the post-pandemic period, the lessons learned about cross-sector engagement continue to be generalizable. Additionally, our sample did not include health care providers, given our goal was to inform how NC InCK could develop cross-sector collaborations with the community, government, and education sectors. This provides a novel perspective of the role the non-medical sector plays in addressing child food needs, but our sample may not be representative of the health care sector. Lastly, our recommendations for collaboration between health care institutions and existing community resources could further complicate disjointed service provision pathways or overburden nonprofits that are already at capacity.

Conclusion

Many of the examined barriers are amendable to cross-sector solutions that improve access to and utilization of food assistance resources for North Carolina children and families. Stakeholders identified a need for programming to address barriers regarding transportation and geographic access to healthy food, reduce high levels of stigma surrounding access to FI resources, increase food autonomy, and improve government program enrollment. As the health care sector continues to implement FI screening more widely in pediatric settings, collaboration between sectors, local public health programs, and novel food security initiatives must be improved to better support North Carolina’s children and families.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance with this manuscript: Eric Monson, Elizabeth Jones, Emma Dries, Emma Garman, Reed Kenny, Erin Winslow, Olga Varechtchouk, Wendy Lam, and Charlene Wong. Thank you to the Duke University Bass Connections program for supporting the research team.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Duke University Bass Connections Grant. Dr. Rushina Cholera was supported by K12-HD105253.

Disclosure of interests

All authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.