In North Carolina, opioid overdose led to 2771 deaths in 2020, making it the leading cause of injury death in the state.1 Opioid overdose deaths in North Carolina have increased 53% from 2018 and 255% from 2011, demonstrating a recent spike during the COVID-19 pandemic and a longer-term trend reflecting the gradual worsening of the overdose epidemic.1,2

The burden of opioid use disorder (OUD) is greatest in rural North Carolina where overdose deaths are 3–10 times more common than in urban centers.3 There are also stark disparities in access to OUD treatment in rural areas, as highlighted in a commentary on opioid-related mortality in the rural United States by Rigg and colleagues.4

Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is the gold standard intervention for OUD. However, large swaths of North Carolina have no access to this life-saving treatment. There have been some recent efforts to innovate treatment delivery in rural settings. Telehealth-delivered medication-assisted therapy (MAT) has an emerging evidence base but has not been widely implemented. A systematic review of telemedicine-delivered substance use interventions identified only five projects targeting OUD.5 In North Carolina, projects have explored telehealth delivery to reduce urban-rural disparities in MAT access6,7 but large areas of the state with few treatment options remain.8–10

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other insurers relaxed rules on telehealth service provision and reimbursement, including MOUD, opening the door for rapid expansion of these services.11 In addition to key policy changes related to telehealth, the pandemic may have served as an accelerator for other forms of innovation for OUD service provision.

Novel approaches for MAT delivery have potential for adoption in rural North Carolina health departments; however, few studies have obtained provider perspectives on the acceptability of novel approaches and facilitators and barriers to implementation. We interviewed community partners in two rural North Carolina counties to discuss the treatment landscape for OUD and opportunities for innovation. For the purpose of this research, we used the US Office of Management and Budget definition of rurality, which is a county lacking an urban core with a population of 10,000 or greater.12

Methods

We conducted this qualitative descriptive study with a purposive sample of health care providers, administrators, and other community partners providing services for individuals who use opioids in Granville and Vance counties, situated in a rural area along North Carolina’s northern border. These counties were selected based on a past research partnership with the local public health department, Granville Vance Public Health (GVPH). In collaboration with GVPH staff, we compiled a list of local service providers and partners. We then contacted these individuals to invite them to participate in a listening session or individual interview. Potential participants were invited by email; those who did not respond received a follow-up email and phone call.

Members of the research study team first facilitated a two-hour group listening session with health care and supportive service providers and administrators to learn about available services and assess gaps and opportunities for telehealth-delivered MOUD and mental/behavioral health services in rural North Carolina. Listening sessions have many similarities to traditional focus groups but place greater emphasis on being participant-driven and facilitating future collaboration among participants.13 At the conclusion of the listening session, we asked participants to name additional local health care and supportive service providers and administrators. We then followed up with one-hour in-depth individual interviews for those who were not able to attend the listening session or were named by listening session attendees.

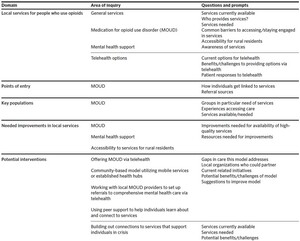

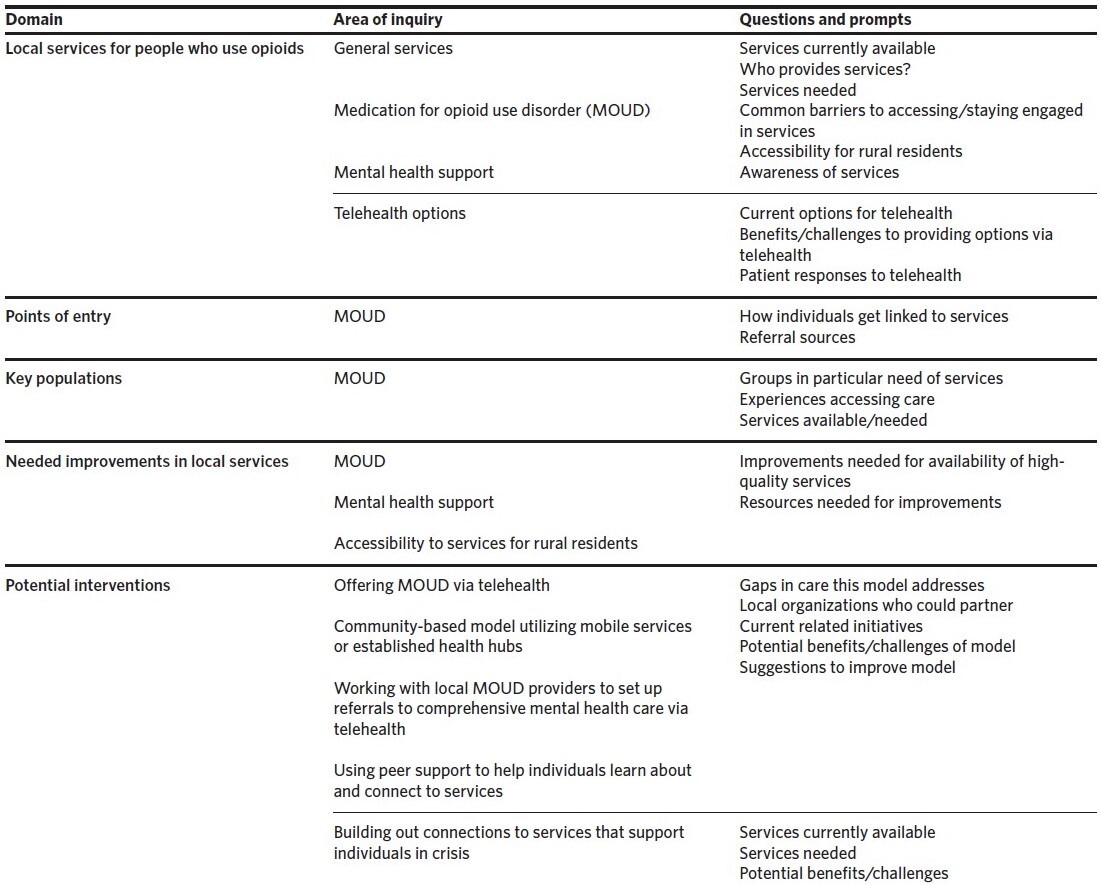

The group listening session was conducted on the Zoom videoconferencing platform and individual interviews were conducted via phone or Zoom from July to December 2021. Interviews were informed by semi-structured guides exploring resources available to individuals who use opioids, gaps in available care and supportive services, and opportunities for future innovation. The development of the interview guide (summarized in Table 1) was informed by prior literature and an ongoing study examining the perspectives of people with lived experience, in consultation with partners at GVPH. Prior to each interview, participants signed an online consent form. Participants did not receive compensation. The study was determined exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the Duke University Health System.

Data Analysis

The listening session and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. We analyzed the qualitative data using an applied thematic approach14,15 and used NVivo 12, a qualitative data software program, to code the data. The team first identified a priori data domains from the interview guide. The team then carefully read each interview transcript and inductively developed themes and sub-themes within each domain during the coding process. A second coder then reviewed the coding for consistency and reconciled any discrepancies with the original coder. Preliminary data analysis began at the outset of data collection. Data saturation—the number of new themes emerging in new interviews—was continually assessed to determine whether further participant recruitment was needed.16 Extracted quotations and code frequency data were used to develop the results report with team feedback.

Results

Fifteen individuals were invited to participate and 10 ultimately took part in a listening session (n = 6) or individual interview (n = 4). Non-respondents did not meaningfully differ in their professional roles or other characteristics when compared to those who agreed to participate. Participants represented a variety of professional services for people who use opioids, including treatment centers, a harm reduction program, emergency medical services, corrections, and public health. Five participants were program administrators, three were health care professionals, and two served in both roles. The health care professionals included a medical doctor, a psychologist, a paramedic, a clinical social worker, and a master’s-trained addiction counselor.

The four domains of the qualitative data were 1) the influence of COVID-19 on telehealth service options, 2) facilitators of services for people who use opioids, 3) barriers to services for people who use opioids, and 4) ideas for expanding services in these rural counties. Emergent themes from the data within each domain are described here.

The Influence of COVID-19 on Telehealth Options

Some local organizations/service providers were starting to offer telehealth options prior to COVID-19, while others began after COVID-19 restrictions were put in place. Participants indicated that prior to the pandemic, both providers and patients had low comfort with telehealth services, the administrative aspects of starting telehealth services were burdensome, and reimbursement was challenging. Changes in insurance reimbursements, quarantines, closures of in-person services, and increased patient comfort with video call technology all encouraged organizations to implement options for remote connections. Patient comfort with the technology arose out of necessity, increased exposure and experience, and improved access to devices and internet connectivity. Health care professionals agreed that relaxed rules from government and other insurers on telehealth service provision and reimbursement were highly influential in driving the expansion of telehealth services. As a result of these changes, several participants reported that their organizations introduced new telehealth programs during the pandemic, while organizations already providing telehealth substantially expanded their offerings.

Organizations described utilizing telehealth by having patients attend an established clinic to connect with a remote provider or connect from a location of their choice (often their homes or cars). During COVID-19, access to wireless internet in the community was expanded when the counties secured grant funding to set up free mobile hotspots. Although these hotspots were intended to support students in connecting to remote learning, they also enabled community members to access telehealth appointments.

Participants explained that increased internet access and options for telehealth in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced transportation barriers and improved access to treatment for individuals with inflexible work schedules. As a result, patients were able to attend appointments more consistently.

“[With telehealth], I’m seeing more folks who [previously] had scheduling conflicts due to working or folks who don’t really have transportation. I definitely think we have seen a decrease in no-show appointments and people are really engaging more because I think they feel a little bit more comfortable in their own space.”

Participants shared that early concerns about patient discomfort with the new format were largely unfounded, as patients were actually more comfortable accessing services from a space of their own choosing. Interview participants explained that although telehealth options can help patients access appointments more conveniently, lack of free internet access or sufficient devices to connect still presents challenges to care access. Additionally, not all care can be provided by telehealth, as patients may still need transportation to the clinic to complete necessary lab work and/or the pharmacy to obtain medication.

Facilitators of Services for Individuals Who Use Opioids

Offering integrated, co-located care. Interviews reflected that when local organizations/service providers offer multiple integrated services “under one roof,” individuals are able to more easily access services that address their needs as a “whole person.” Participants highlighted that patients seeking MOUD benefit greatly from integrated care or seamless referrals for other services, including primary care, pharmacies, mental/behavioral health, psychiatry, harm reduction programs, and supportive services. These linkages empower patients to improve health broadly and address interrelated challenges and stressors that can hinder treatment benefits. In addition, offering integrated care allows for more streamlined care and collaboration among providers.

“We do have a primary care doctor, so if someone has any other medical needs they can be seen here. We are here to address the whole person… Focusing on addiction is really hard if [someone is] worrying about where they’re going to sleep, or if they’re worried about if their children are going to have power when they come home.”

Patient preferences for co-located care were further amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were being encouraged to minimize contacts with other people. Accessing multiple services at the same location offered benefits in terms of both improving care access and minimizing potential COVID-19 exposures.

Hiring from the local community. Interview participants discussed the benefits of hiring staff from the local community, highlighting that the personal experiences of these staff members can lead to better understanding of the local context and resources available.

“I’m from this community, so I don’t think I have the same eyes of stigma that people from the outside [may have] looking in. I see that sometimes what we professionally recognize as addiction, family systems do not see as addiction at all. It’s a coping mechanism. It’s the way we celebrate. It’s the way we manage hard feelings.”

Barriers to Services for Individuals Who Use Opioids

Low availability of after-hours and crisis services. Participants explained that there are few local options available for substance use and mental/behavioral health, and that individuals needing these services often face long wait times. In addition, low availability of services offered outside of normal business hours often means that during a time of crisis, no services are available. As a result, people experiencing a mental/behavioral health crisis or substance use crisis may be triaged to the emergency department or even jail.

“I think [our community] does really well from 8 in the morning to 5 in the evening, but we probably need more help from 5 in the evening till 8 in the morning. [The local crisis facility] is really our only go-to and if they’re maxed to capacity, you end up in an emergency department.”

Service providers attempted to maintain regular hours during the COVID-19 pandemic, but some were required to temporarily close or reduce their hours, which further impacted patient access to crisis support. Limited options for care and services outside of traditional business hours also lead to challenges in linking individuals to services after they are released from incarceration, as release times can be unpredictable. Participants felt there could be improved communication and collaboration between service providers and corrections.

Cost of services. Participants highlighted cost as a prominent barrier to accessing services and paying for medication. Several participants indicated that the lack of Medicaid expansion in North Carolina meant that many rural residents were uninsured or underinsured, which exacerbates challenges with treatment and medication affordability.

“Cost of course comes up as a huge barrier to accessing the health care people really need and that is certainly the case with behavioral health and mental health services or substance use treatment. They’re very expensive services, and so even if people feel like there’s a place they could go to make an appointment, they don’t feel they can afford that service.”

Limited staff capacity. At current staffing levels, it can be difficult for organizations to keep up with patient needs for referrals to supportive services and to engage in community outreach while still serving more immediate needs. Within local health departments, heightened demands for other efforts, such as COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, sometimes led to reduced attention and resources for MOUD programs. Interview participants explained that local organizations and service providers often lack the time to build relationships with one another, which means they are not always aware of services that are offered locally and they sometimes face challenges coordinating when referring patients.

“It seems like the connection piece has kind of fallen by the wayside due to the other fires that are happening. It’s going to require me to reintroduce, ‘This is what we do, this is why we do it, and this is what our services look like.’ That’s how you get the buy-in first, so I’m having to rebuild connections.”

Participants expressed that funding to hire more staff can be difficult to obtain and is often restricted by grant timelines. In addition, there can be restrictions on how funds are used based on funder discretion, which can prevent organizations from being able to hire necessary staff like peer support specialists.

Social drivers of health. Interview participants noted that many people in their community face challenges related to transportation, housing, and employment. Local options for public transportation are minimal and grant-funded options for transportation to medical appointments are difficult to coordinate and often not timely. Many of the social support services that do exist were suspended for extended periods during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When OUD treatment is not available locally, transportation challenges can prevent individuals from linking to alternative care options in surrounding counties. Many people in the community also have challenges accessing stable housing and employment, which can compound barriers to engaging in care and making positive life changes.

“I would say housing is a huge barrier in the area. That’s a lot of folks’ biggest complaint and that’s kind of what sets the downward spiral for a lot of people.”

Increasing cost of living, housing costs, and expiration of the federal eviction moratorium during the pandemic contributed to further concern about housing security for individuals in OUD treatment.

Interview Participant Ideas for Improving Services for People Who Use Opioids

Improving collaboration among local service providers. Participants described disruptions in communication and collaboration among service providers during the COVID-19 pandemic, which they attributed to the need to rapidly adapt to changing circumstances within their own organizations. Formalizing opportunities for local organizations and service providers to connect and collaborate could help to streamline services for people who use opioids. For example, closer professional ties could ensure there is awareness of which services each organization is able to offer as well as better communication between organizations. This would improve the linkage of patients to needed care and services. For some organizations, transitioning to electronic records would streamline the process of sharing information and linking individuals to care and services.

Addressing needs as a whole person. A formalized screening process for patient-specific needs related to social drivers of health could help ensure that individuals receive more patient-centered care and have support in addressing their needs as a whole person. Improving grant-funded transportation offerings or other novel transportation solutions could help address barriers to accessing services. New strategies for addressing challenges related to affordable housing, support to pay utilities, or food insecurity, particularly among those not eligible for or connected to existing programs, should also be explored.

Increasing access to services for substance use and mental health. Expanding hours that services are offered for people who use substances could help remove barriers for patients who cannot take time off work for their health appointments or who are experiencing a crisis outside of traditional service hours. There is also a need for services for patients with more complex mental health needs, and these needs appeared to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic. Establishing partnerships among institutions or providers that can offer MOUD, mental health care, and medication management via telehealth can help increase capacity. Partnerships with larger health systems or academic medical centers from outside these counties to provide telehealth treatment may serve the community when local availability of providers is low.

Community-based hotspots that provide internet access and devices equipped with telehealth options for MOUD and/or mental health care may help address transportation and technology challenges. Additionally, providing services via community-based satellite clinics or a mobile health unit could help bring care to the community and address issues with transportation. One option would be to partner with pharmacies to offer care on-site or via telehealth, similar to options provided for COVID-19. Offering mental health and substance use services that involve the whole family system could help address problematic substance use across generations and help create more supportive systems for individuals in recovery.

Increasing staff capacity. Exploring opportunities to fund more staff, such as peer support specialists, could help provide support for developing discharge plans and linking individuals to care after release from jail, increase capacity to address social drivers of health, and link individuals to needed supportive services. Funding could also be used for additional hiring to support patient care and make more time available for service providers to engage in community outreach, which will build trust and increase awareness of services.

Discussion

Despite the urgency of addressing opioid-related challenges and overdose, many residents in rural North Carolina struggle to access OUD treatment. In this qualitative analysis, interview participants shared that policy changes enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have served as an accelerator for telehealth and other forms of treatment access for rural communities. Participants described several barriers to telehealth treatment for OUD that existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, including lack of comfort in using telehealth among both providers and patients. However, during the pandemic, telehealth offerings were rapidly expanded and became a routine part of care with very positive results.11

Facilitators of telehealth expansion included increased comfort with experience over time, improved billing regulations and reimbursements related to treatment delivery, and improvement of free community wireless internet access. Future policy and regulation related to OUD treatment access must continue to consider patient safety, but must also avoid stifling the innovation of safe, effective, and life-saving treatment approaches, such as telehealth-delivered MAT.17,18 Our findings demonstrate that internet access is a critical public utility in the modern era. Improving community access to wireless internet enables telehealth treatment and reduces barriers to care, such as time commitment and transportation challenges. This is particularly critical for rural populations with reduced options for and access to care.19

Participants described the value of strong coordination and referral among service providers in the community. This included a desire for more integrated, co-located services, such as MOUD, primary care, infectious disease care, mental health counseling, psychiatry, pharmacy, and harm reduction services.20–22 Combining services in a single setting could serve to reduce the burden on patients of attending multiple visits at different sites and lessen the likelihood of being lost to follow-up during the referral process. One example of integrated treatment with an emerging evidence base is the Collaborative Care Model of behavioral health and substance use treatment in primary care, which may be a promising direction for service expansion.23 Other options include bringing treatment services into more community settings, potentially through satellite clinics, mobile treatment units, or partnering with existing community sites, such as pharmacies, for pop-up clinics. Such community-based models could also be equipped with telehealth to link with off-site providers.

Participants expressed a strong need for improved after-hours and crisis services. Participants suggested adding new crisis services programs, adding stronger crisis response to current programs, and conducting education with current providers to improve collaboration among existing services. Telehealth could also bring added value to this area, as crisis services could be offered remotely by an on-call provider and minimize the added burden on already-thin local resources.24

We made a concerted effort to recruit from multiple organizations in these two rural counties; however, perspectives may not be representative of the broader professional community in North Carolina or elsewhere. Additionally, this analysis did not include the perspectives of people with lived experience related to opioid use, which we will solicit in an upcoming study.

Conclusions

Policy changes enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have served as important accelerators for telehealth-delivered MAT, yet considerable gaps remain in access to effective treatment in rural communities. It will be critical to maintain recent progress in policies that support telehealth treatment and expand internet access for rural communities. Participants made strong arguments for the value of integrated models that combine MAT with other forms of medical care, mental health services, and social services, as well as novel community-based treatment and crisis response models. Together, these strategies can improve linkage to effective OUD treatments, reduce the burden of the opioid epidemic, and save lives in the state.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Center for Nursing Research at the Duke University School of Nursing. We acknowledge additional support from the Duke School of Medicine Opioid Collaboratory and the Duke Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (5P30 AI064518). The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.