North Carolina Medicaid beneficiaries represent a quarter of the state’s population.1 In 2015, the North Carolina legislature passed a law directing the Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) to transition Medicaid from a fee-for-service (FFS) model to a risk-based managed care delivery system.2 North Carolina received an 1115 waiver approval from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) to transition 1.6 million Medicaid enrollees (excluding “special populations” with mental, intellectual, and developmental disabilities) to 1 of 6 private managed care organizations (MCOs) through an initiative called Medicaid Transformation. This made North Carolina the 41st state to transition to managed care.3 This insurance reform is part of a national trend toward alternative payment models to support better care delivery, address social drivers of health (SDoH), and improve health outcomes.4,5

Implementing this large-scale payment model change during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic created challenges and impacted efforts to engage, educate, and enroll participants into the new plans.6 To prepare beneficiaries for the transition to managed care, the state rolled out a multi-pronged approach to communicating the changes.7 NCDHHS mailed notices explaining the changes, launched a dedicated website as well as an online portal for enrollment, designated a Medicaid ombudsman to support enrollees, and hired an enrollment broker to manage enrollment.8,9

In early 2021, focus groups were held with North Carolina Medicaid beneficiaries to learn about early perspectives prior to Medicaid Transformation and how enrollees perceived the new changes might impact their quality of life and health.7 Beneficiaries expressed concerns with communication during the transition; some expressed confusion about navigating the website, reported not having enough time or information to pick a new health care provider, and were concerned about how changes would impact their health coverage.7 To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the impact of North Carolina Medicaid Transformation on the Medicaid enrollee experience right after the transition to managed care.

To assess the early enrollee experience following the transition to managed care, we conducted a mixed methods study that included Medicaid enrollee input through surveys and focus groups. We also reviewed the health care records data of a representative population of Medicaid enrollees in Forsyth County, North Carolina. This paper discusses the focus group findings, centering around enrollee experiences with the process of Medicaid Transformation, impacts on health care access and cost of care, perceived quality of care, and SDoH.

Methods

Study Design

We used focus groups to explore the perspectives of people who received Medicaid benefits and how the shift to risk-based managed care impacted their access to and experiences with health care.7,10

Setting and Population

We conducted this study at a major academic medical center in the fifth-largest urban area in North Carolina. All participants were patients within the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (AHWFB) system, a large integrated health system comprising a tertiary care hospital, four community hospitals, and over 300 ambulatory practice sites. AHWFB is in-network for all plans offered in the region, including AmeriHealth Caritas, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Healthy Blue, United Healthcare, WellCare, and Carolina Complete Care.11

Participants were eligible for the study if they: 1) were patients at AHWFB with at least one primary care visit covered by Medicaid since 2019; 2) consented to participate in the longitudinal study; 3) were insured by Medicaid or were a parent/guardian of a child insured by Medicaid; and 4) were aged 18 years or older. Participants were excluded if they did not speak English, due to study staff limitations.

A study team member contacted a convenience sample of eligible participants by phone to explain the purpose and procedures of focus groups and determine potential participants’ interests. Eligible participants were invited to attend 1 of 4 focus groups, which were scheduled at convenient locations in the community easily accessible by car or public transportation. The time and day of the week varied to help provide a convenient time for focus group participants to attend.12 All sessions occurred in person between January and March 2022; all participants were offered transportation and child care and received a free meal and a $35 gift card for participating.

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

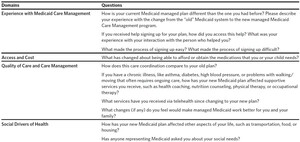

Through a detailed review of the literature, consultation with outside experts, and input from our steering committee (members from the community and the hospital system), we developed a focus group guide (Table 1).13 The guide was pilot-tested with representative patients and community members for face validity. Four focus groups were conducted by trained and experienced facilitators in English.14

Informed consent was obtained prior to conducting focus groups. All focus groups were audio-recorded, and a note-taker was present to capture additional information. In one focus group, the audio recorder stopped working during the middle of the focus group session; verbatim notes were used as supplementary data for the remainder of the session.

Focus groups lasted between 40 and 52 minutes, with a median time of 45 minutes. We collected demographic data through the self-report of participants after focus group participation.

Data Analysis

Focus group audio files were transcribed verbatim and verified for accuracy by a study team member.15 After reviewing all transcripts, two study staff members developed a draft codebook including inductive and deductive codes. The codebook was reviewed by the study team and edits were made accordingly. Two study team members independently coded the transcripts using a text-based analysis program, Atlas.ti Version 9 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany),10 and met regularly with each other and the study team to resolve discrepancies and reach consensus. Once coding was complete, reports were run for each code and were summarized. Finally, these summaries were reviewed and synthesized, and themes were derived by their prevalence and salience within the data.

Results

Participant Demographic Data

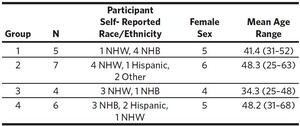

We conducted four focus groups with a total of 22 participants (N1 = 5, N2 = 7, N3 = 4, N4 = 6) who had experienced the Medicaid Transformation process. Participants’ average age was 43 years (range: 25 to 68 years); most participants were female (n = 20) with two male participants. Eight participants self-identified as non-Hispanic Black (NHB), nine as non-Hispanic White (NHW), three as Hispanic, and two as Other. Table 2 summarizes participant characteristics.

Overarching Qualitative Themes Describing Participant Experience and Perspectives

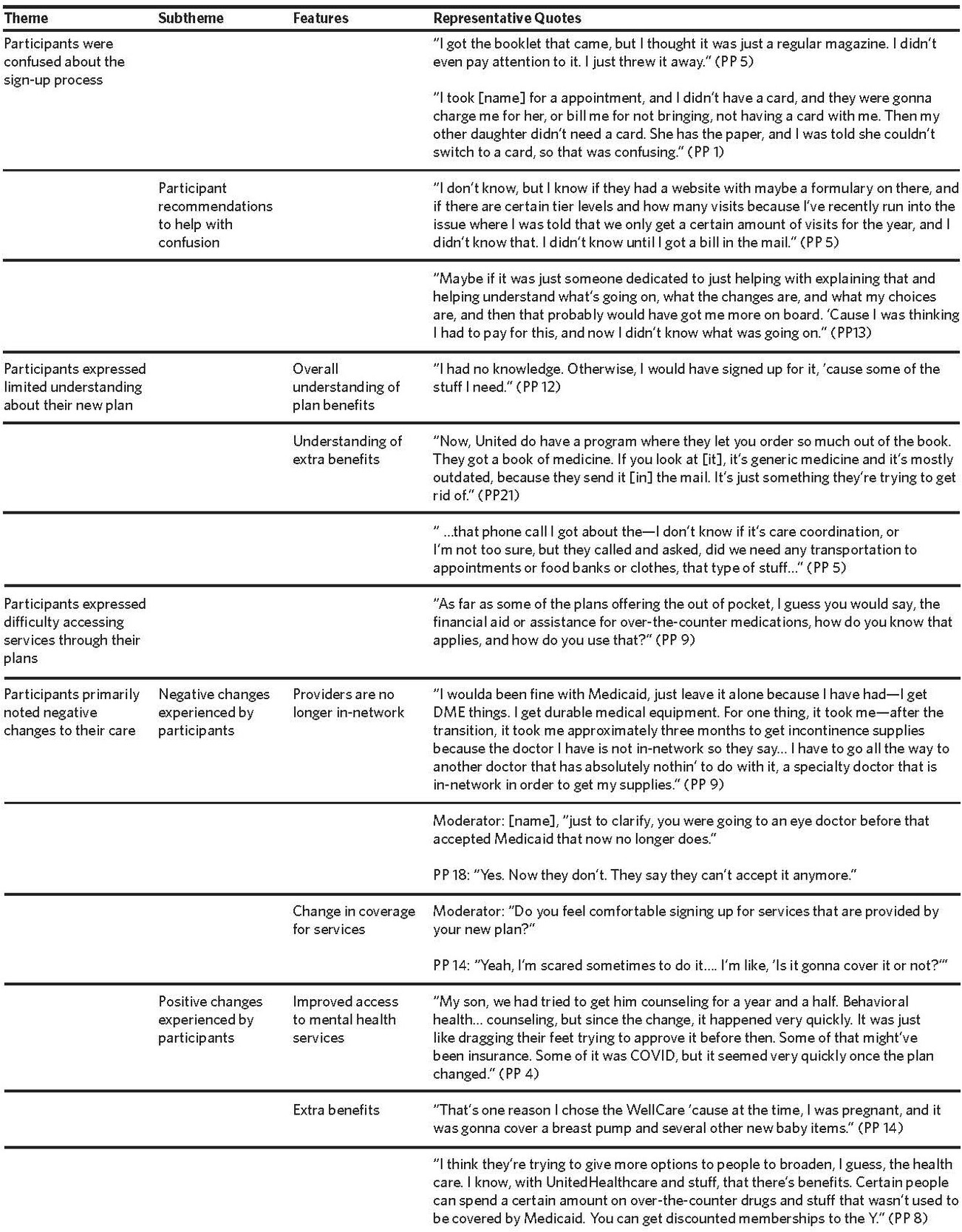

We identified four major themes associated with participant experience related to Medicaid Transformation: 1) Participants expressed confusion about the signup process; 2) Participants had a limited understanding of their new plans; 3) Participants expressed difficulty accessing services through their plans; and 4) Participants primarily noted negative changes to their care. Table 3 provides a comprehensive list of representative quotes reflecting each theme and sub-theme.

Participants Expressed Confusion About the Sign-up Process

As participants discussed their experiences with signing up for Medicaid services, they expressed confusion with the sign-up process and provided recommendations for alleviating this confusion.

Participants experienced confusion specifically about whether they needed to sign up, how to sign up, and the differences between the plans. Due to confusion, most participants did not pick their plan (n = 16) and were auto-enrolled into a new plan by Medicaid. Participants who did not choose their plan reported the following reasons for not doing so: they allowed the plan to be chosen for them, they missed the date to enroll, or they did not realize that they needed to do anything. One participant explained, “Like I said, I only knew and looked at all the plans before they actually picked, but they ended up picking because I didn’t pick anything. Because like I said, I didn’t see anything that was beneficial to my son…I was like, ‘Well, I’ll come back,’ but I didn’t even have time to come back.” (PP 19)

Three participants mentioned that they didn’t realize the sign-up package was important mail. One participant who was confused about the mailing stated, “I about threw it away 'cause I thought it was junk.” (PP 14)

Another source of confusion was the transition from old to new Medicaid cards. Participants expressed confusion about why they received new cards, and why cards varied among the adults and children of the same household. One mother explained, “I was kind of confused 'cause I have three boys, and [name] and I have another child that we were sent the AmeriHealth Caritas card, but my other child has the regular card, so I was kinda confused about why the other two get one card, and then the other one didn’t.” (PP 5)

Recommendations to Help with Confusion Around Sign-up Process

As a result of the confusion, six participants suggested that it would have been helpful to have a Medicaid worker call them at the time of sign-up and explain the different plans. They felt that this would have helped them feel more informed. One participant recommended, “I think it would be helpful to have a specific Medicaid navigator person or help desk if you do have questions like that, or someone that calls and checks in with things like that, so you’ll know about 'em.” (PP 1)

Participants Expressed Limited Understanding About Their New Health Plan

As participants described their understanding of their new plans, they expressed limited understanding of what services were covered and what extra benefits were made available through the new plans.

Three participants indicated that they did not choose their own Medicaid plan and were unaware of which plan they were automatically transitioned to. One participant was unaware that Medicaid had transitioned at all until the day of the focus group and asked for clarification: “I wanna know what’s the difference, ‘cause you sayin’ transition. Everybody was supposed to transition over? 'Cause I didn’t do none of that.” (PP 12) Another participant asked the focus group facilitators the following question when they were asked about which plan the participant had been transitioned to: “I was going to ask you, how can I find out?” (PP 17)

Only about a third of participants were aware of extra benefits provided by their plans; half of these were influenced to pick their plan because of these benefits. One participant noted how extra benefits were helpful for a family member: “She also gets credit for over-the-counter medications…before, we didn’t have that.” (PP 1)

Others who were not aware of the new services reported that they would use them if they were part of their new plan. Two participants became very interested in extra benefits once hearing other participants speak about them, asking how they could receive these benefits. Another participant responded to the group conversations around the new extra benefits by stating, “Okay, I guess that’s relevant here though because you all is talking about all these benefits to having Medicaid that I didn’t even know existed; going to the Y[MCA] and covered medical equipment and stuff.” (PP 20)

Participants Expressed Difficulty Accessing Services Through Their Plans

Some participants reported being aware of extra services available through new plans to address SDoH (e.g., transportation assistance), but few reported accessing these services. One stated, “They mention it [transportation assistance]. It’s not a need, but they do send something in the mail just reminding you that that [it] is available.” (PP 1)

Some reported that they had difficulty accessing the extra benefits; they were often confused about whether the benefits were covered under their new plans or not. When one participant realized dental and vision care were covered, the participant said, “I just recently had a call 'cause I was told I had vision and dental, and I was like, ‘Really? I didn’t know that.’ It took me a week to get a hold of my case worker.” (PP 14) For many participants, similar attempts to communicate with Medicaid caseworkers to clarify their benefits were unsuccessful.

Many stated that they were unsure whether some of the extra benefits were made available through their new Medicaid plans or through other health system-based social service personnel. One participant stated, “I’ve been getting those calls, but maybe from somebody from the hospital but not from Medicaid and not from the insurance company.” (PP 22)

Participants Primarily Noted Negative Changes to Their Care

All but two participants reported changes in care since the Medicaid Transformation, the majority of which were negative changes. Participants discussed challenges with identifying in-network providers, especially when their previous provider had become out-of-network, and vision or dental providers; these challenges led to scheduling difficulties.

Negative Changes Experienced by Participants

Participants mentioned being “scared” to access health care after transitioning to managed care; they were unsure what services or treatments would be covered. Others mentioned that appointments, treatments, and the medical equipment they needed were no longer covered by their new plan. One participant expressed this concern, stating, “I didn’t know until I got a bill in the mail, and I’m like, ‘I thought this was covered,’ and they’re like, ‘No, you only have a certain amount.’ It’s just confusing to me when I don’t know anything, and I’m expecting something that I’ve been getting, and now I’m not getting it, or now I’m just getting billed for it when it was covered in the past.” (PP 5)

Many participants mentioned difficulty accessing services because providers they had previously seen outside of the AHWFB system did not accept their new plans. This difficulty accessing care led to service delays. Seeking new providers took time, and the new providers had wait times for new patient appointments, resulting in frustration for some. One participant explained that her family did not move from the city as previously planned, because they could not find a provider in-network. She stated, “… I was having a really hard time in finding a provider on the network. Also, everybody else, of course, have a waiting list… We ended up staying here in [city].” (PP 22)

Participants also discussed difficulties accessing medications and medical supplies to treat chronic illnesses and pain due to changes to coverage, cost, or the discontinuation of auto-refills for prescriptions under their new plans. They expressed frustration with their ability to access medications and medical supplies previously covered prior to Medicaid Transformation. One participant diagnosed with a chronic illness explained, “I suffer with high blood pressure, and I’m on five different kinds of blood pressure medicine. When I went to the pharmacies to get my medicine, they [were] refusing to give it to me… they’d be ‘denied, denied.’” (PP 21)

Participants who reported being no longer able to auto-refill prescriptions stated that this change made chronic illness management challenging. One participant explained difficulties with keeping up with medication refills needed for their family, noting, “Their medicines were on auto-refill. It’s hard. I’m 54 years old. Tryin’ to keep up with my 16 medicines, my 16-year-old’s on six or seven different medicines, my 12-year-old’s on four or five, and my eight-year-old’s on four. I’m tryin’ to keep up with all of that every single month when I was on the auto-fill. Now I’ve got to keep up with that. That’s not easy.” (PP 7)

A few participants discussed being frustrated by higher medication costs after switching plans, often making their medications no longer affordable. One participant explained, “I have seen changes as far as my medications. What I pay for my medications every month is over $100 a month when I was only payin’ $3 apiece for my meds.” (PP 7)

Recommendations to Address Negative Changes

To address these challenges, participants suggested having a consistent Medicaid staff member help them navigate coverage. One participant explained, “You don’t have only one person to call; you have to make too many phone calls just to find one answer.” Other participants echoed similar experiences, stating that when they called Medicaid, they were unable to reach a real person and did not receive return calls. Participants would prefer having a direct email or phone number for a consistent worker to help them navigate their plan and coverage.

Positive Changes Experienced by Participants

Of the participants who reported positive changes, seven mentioned that the new plans had increased emphasis on mental health services. One participant appreciated that their children now received mental health screenings. Others mentioned that mental health appointments were approved and scheduled in a timelier fashion.

“Like I said, I think there’s a big emphasis on the mental health aspect… they do offer the screenings. Both of my kids were able to get screenings. My oldest here has anxiety and depression, so her doctor has been reachin’ out.” (PP 1) Some participants stated that the new benefits offered by their plans constituted a positive change. For those who picked their own plan, the availability of extra benefits was a factor in their decision.

Discussion

Our focus groups of early enrollee experiences of North Carolina Medicaid Transformation highlighted four main findings. First, participants were confused about the process for enrolling in the new managed Medicaid plans; many felt they had a limited understanding of their new plans. Second, participants had varied understandings of extra benefits provided through new plans, and many expressed difficulties accessing these services. Third, participants noted primarily negative changes to their care after enrollment in new plans that directly impacted their care.

Lastly, one unintended outcome of the focus group sessions was that participants felt comfortable sharing specific feedback, including recommendations to help improve the experience of understanding and accessing Medicaid services.

The finding that participants were confused about the enrollment process and services provided is consistent with previous studies evaluating transitions to Medicaid Managed Care (MMC). For example, participants of a 1996 North Carolina MMC demonstration program cited similar concerns regarding a lack of awareness of services offered by plans.16 By contrast, in that study, an independent enrollment broker was utilized as the first step to educate enrollees about available plan options, in addition to conducting the plan changes, which potentially resulted in more positive feedback about their health care experiences under MMC. Across other states, such as Tennessee, extensive confusion resulted after the introduction of MMC for both beneficiaries and providers because educational resources regarding plan selection and counseling were limited.17 Minnesota and Oregon, on the other hand, provided active education during the transition, minimizing confusion and the need to auto-enroll a large number of individuals. These studies highlight that the typical model of MMC, in which the burden of education, awareness, and decision-making falls on enrollees who are often not empowered with knowledge or access to resources, may not best serve MMC recipients.18 Instead, collaborations between state Medicaid programs, MCOs, and Medicaid recipients to provide input on consumer education and engagement and product rollout strategies seem more effective.19

Most participants in our study reported negative experiences with Medicaid Transformation, particularly around accessing care and consistent coverage. Our study’s findings of negative participant experiences contrast with studies from other states, such as Maryland and Minnesota, where participants reported high satisfaction with services after transitioning to MMC.17,20 A 2012 review of MMC on cost savings, access, and quality found that given the heterogeneity of state MMC programs, direct comparisons were not possible; some states were more successful than others in these different areas.21 A recent review incorporating more high-risk populations in MMC indicates the potential for improved quality of care, although variability will exist across state-specific programs, and additional research is needed to generalize findings.22

Years of research have highlighted the longstanding negative impact that SDoHs have on morbidity and mortality, and the increasing importance of addressing these risk factors in a health care setting.23–27 Several state Medicaid programs address SDoH to provide “whole person” care.28–30 As MMC programs evolve and grow, knowledge-sharing and guidance on promising practices addressing SDoH should be shared.31 There are many opportunities for Medicaid insurers to address SDoH, but barriers exist in financing strategies, identifying best practices to allow for effective partnering with community organizations, and scaling.23 Future research may help elucidate effective reimbursement strategies for SDoH services. The NCDHHS is testing and evaluating the impacts of addressing SDoH through Healthy Opportunities Pilots.32 Additionally, NCDHHS can benefit from Medicaid enrollee input, such as recommendations noted in this publication, to help guide strategies for effectively addressing whole person care.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, participants were recruited from a single institution in the Southeastern United States; results may not be transferable to other institutions. Second, participants who agreed to participate in a focus group are likely not representative of all Medicaid Transformation beneficiaries; only English-speaking participants were included. Participants were not given the opportunity to validate themes prior to final analysis, but they will be provided with study findings via a report and/or infographic.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust. The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Iglesia Cristiana Sin Fronteras and Help Our People Eat of Winston-Salem for allowing our team to host focus group sessions in their spaces. Research supported in part by the Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Shared Resource (Q-PRO) of the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center’s NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197. Dr. Zimmer is supported by a Health and Human Resources Administration Geriatric Academic Career Award through Grant Award Number K01HP33462. Dr. Palakshappa’s work on this project was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL146902. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of the Health or Health and Human Resources Administration.