Introduction

Over the last several years, policymakers, clinicians, and child health advocates have considered how our health systems can support whole-person health, an approach that seeks to address the physical, mental, behavioral, and social needs that together impact health. Shifting systems that have traditionally focused on physical health to this broader approach has been prioritized through a growing number of health policy decisions across North Carolina. The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) has launched a series of initiatives, including widespread social needs screening, the Healthy Opportunities Pilots, and the cross-sector collaboration software NCCARE360, to test strategies that “buy” health and not solely health care.1 Integrated Care for Kids (NC InCK) joined this landscape in 2020 with a focus on strengthening whole-child health.

The Integrated Care for Kids Approach to Whole Child Care

NC InCK is one of seven InCK pilots across the country testing approaches to promote a model of integrated care. The initiative is funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and is designed to strengthen integrated, whole-child care. NC InCK is focused in five central North Carolina counties: Alamance, Durham, Granville, Orange, and Vance. Nearly 100,000 children with Medicaid insurance coverage are included in the model, which is run in partnership between Duke University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and NC Medicaid. The model collaborates with Medicaid’s Prepaid Health Plans and Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC) to offer care management and community- and clinic-based supports, such as education and nutrition resources, to children and youth aged 0–20.

The InCK model defines whole-child care through 10 core child service areas (Table 1). These services focus the NC InCK team on building the capacity of health systems to meet the unique needs of children in areas outside the clinic walls, including schools, child welfare, juvenile justice, and early childhood education and development. We describe our approach to integrated care as three strands of a braid that together form a child-focused approach that identifies needs, provides robust care management, and focuses health care investment through value-based payment models.

Based on our experiences with NC InCK, we present priority learnings to further the vision of whole-child care in our state: 1) testing long-term, preventive models of care management focused on children’s diverse needs; 2) collaborating with schools to receive referrals, coordinate care, and strengthen services; and 3) maintaining ties between state divisions of Child Welfare, Juvenile Justice, and Medicaid to best serve children and families (Figure 1).

A Longer-Term, Multidimensional Care- Management Model

To meet whole-child needs, health systems and health plans may need to take a longer-term approach than traditional 60–90-day medical models of care management.

Caring holistically for a child requires enhanced knowledge of the existing landscape of supports and a strategy for meeting needs when community and public supports are in limited supply. NC InCK’s year-long care management model pairs families with a family navigator, a care manager who supports a longitudinal journey to improve a child’s well-being.

Addressing housing needs is one aspect of providing whole-person care through the NC InCK model. Every week, new children and families facing housing instability or homelessness are engaged in the NC InCK model. Our experiences with these families exemplify the challenges that many face within the current system. The limited supply of affordable housing, long waitlists for subsidy support, and increasing housing prices in our region leave limited resources for most families. In Durham County, the waitlist for housing vouchers is 23 months, while in Granville and Vance counties the wait is more than five years.2 NC InCK care managers actively work with families to build their capacity to navigate housing options. We recently launched a process that makes it easier for care managers in health systems to connect children facing housing instability to the Housing Specialist at each Medicaid Prepaid Health Plan.

If a family has a housing need, whole-child support means actively layering resources in food, education, utilities, and early childhood to limit financial burdens (Figure 1). For example, school supports, such as those laid out by the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987,3 can make sure children stay enrolled in their home school and have transportation while supports for utilities and food can offset expenses and open up funds for housing.

Coordinating these supports requires substantial resources from families, even when working with a care manager. Implementing a whole-child approach alongside families with various social needs requires capacity-building among care managers. NC InCK has designed monthly Integrated Care Rounds that ensure care managers have the concrete supports they need to meet the diverse needs of families. These trainings are free and available on NC InCK’s website for all care managers in North Carolina or other states to use.4

However, training alone is not enough. For our health systems to meet whole-child needs, care managers also need sufficient resources to spend time with each family and a network of community supports that are adequately funded to meet demand. NC InCK is hopeful that our lessons learned can ultimately inform a model of enhanced care management paired with resources like rental assistance and medically tailored meals that meet the physical, social, and environmental needs of children and families.

Whole-Child Care Must Include Collaboration with Schools

Children may spend 30 minutes in their annual well-child check, but for most of the year, children and teens spend 30 hours a week in school. To provide whole-child care, our systems have to be equipped to provide services on school campuses, communicate and work with school staff, and take referrals for care from schools. We can illustrate the importance of collaborating with schools with a recent experience:

Earlier this year, a mom asked an NC InCK care manager for help navigating her 16-year-old son’s hesitancy to attend therapy, as well as academic and behavioral challenges at school. The care manager spoke with the 16-year-old adolescent at length and learned of his passion for football. The care manager worked with the mom to collaboratively shift their focus to supporting the youth in returning to the football team, which helped motivate him to start attending therapy. They also worked closely with the school and football coach to create a plan—if he passed four of his five classes, he could rejoin the team. He successfully achieved this goal and rejoined the football team this year.

Our approach to integrating with schools focuses heavily on building the capacity of care managers to 1) listen to families about their children’s education needs, strengths, and interests, 2) collaborate with schools to identify solutions for students, and 3) make sure the process of consent and information-sharing enhances opportunities for school-health collaboration. NC InCK has designed a two-way consent form that we hope makes it easier for health care and education sectors to work together.5 NC InCK also coaches care managers to engage adolescents in their own goal-setting and care as part of a whole-child approach.

School staff are critical to a preventive approach that identifies children before a crisis—especially for children who do not regularly access medical and behavioral health care. This fall, NC InCK will launch a pilot with the Alamance Burlington School System to allow school nurses to refer children for care management. We hope that this pathway for direct referrals from schools will lead to a model that Prepaid Health Plans and Local Management Entities can follow. Centralizing referrals through one entity is especially important in the current Medicaid managed care landscape so that schools don’t have to build multiple referral pathways based on the primary care provider attribution of the child. CMS also released new guidance this spring for state agencies to pursue more avenues for Medicaid-funded services on school campuses.6

Preparing for School: Getting Clinics More Involved in Kindergarten Readiness

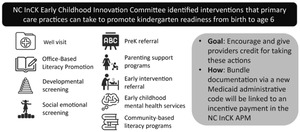

In 2021–2022, NC InCK partnered with NC Medicaid and the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction to link health data on children with Medicaid insurance to their kindergarten readiness scores. The new analysis found that only 41% of Medicaid-enrolled five-year-olds in NC InCK met teacher observations for kindergarten readiness as measured by the Early Learning Inventory (ELI).7 NC InCK is testing ways that health systems can use this kind of data to help children enter school ready to succeed. Traditionally, health care quality and performance measures for children have focused on vaccinations and well-child checks. We’ve partnered with NC Medicaid, health plans, and Duke, UNC, and CCNC to test a child-focused alternative payment model (APM) with a performance measure for kindergarten readiness (Figure 2).8 Through this payment model, if practices take a series of evidence-based actions to promote school readiness with children aged 0–5, they will receive performance payments at the end of the year.

While NC InCK’s APM can facilitate clinic referrals to key supports like pre-K, child care, and literacy programs, there is still a great need for increased funding for the early childhood supports to which children are referred. Unpublished data from NC Medicaid and a review of publicly funded pre-K slots in each of NC InCK’s six school districts show the capacity to serve only 45% of Medicaid-insured four-year-old children this year.

Bridging Systems for Children in Foster Care

Relationships between child-serving sectors are siloed and need regular attention to serve families in a coordinated manner. NC InCK is particularly focused on this for children in out-of-home placements, such as foster care. Maintaining relationships between divisions of Child Welfare, Medicaid, and Juvenile Justice requires substantial capacity of InCK staff and a focus on serving those who matter most: the children in our care.

In partnership with CCNC and local North Carolina Division of Social Services (DSS) offices, NC InCK and NC Medicaid are piloting an approach to enroll all children who are in foster care across five counties in the NC InCK model. As of June 2023, 85% of the children in foster care in NC InCK counties are engaged in care management, which is much greater than previous levels (unpublished data). Our staff provide daily support to both CCNC staff and DSS social workers to maintain communication and relationships for these children and families. NC InCK also provides in-depth support to care managers at CCNC who connect children to physical, mental, and dental care and supports for food, other basic needs, education, and housing. Our goal is that CCNC’s care management through NC InCK can reduce foster placement turnover, increase access to preventive care, and reduce the strain on DSS social workers so they can better meet whole-child needs.

What’s Ahead: Systems-Level Investment and Capacity-building to Meet Unique Needs of Children

Children and families will continue to need increased investment in early childhood supports, housing, and mental health care, among other areas. NCCARE360 will continue to be a platform for learning how closed-loop referrals between health care and community supports can improve child well-being and identify where gaps in system capacity need the most investment.

Finally, our hope is that the NC InCK model can do more to strengthen the health care sector’s understanding of the unique needs of children and bring examples of the impact to care management quality of capacity-building to meet these needs across domains like early childhood, schools, child welfare, and juvenile justice.

Disclosure of interests

S.A. led the design and launch of the NC InCK model at Duke Health in the role of Managing Director. R. Cholera serves as the Executive Director for NC InCK. R. Chung serves as Population Health Director for NC InCK. K.F. serves as Early Childhood Director for NC InCK. M.S. serves as Health Director for NC InCK.