Pre-Pandemic State of Youth Behavioral Health

Children, adolescents, and young adults are our most treasured resources for society’s future. However, each developmental phase of youth and early adulthood can be fraught with traumatic events, inequality, housing and food insecurity, resource constraints, educational and employment barriers, and lack of health care access—all contributing to adverse health outcomes and behavioral health challenges.1 Youth are also at a greater risk for developing a mental health disorder due to a confluence of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors.2 It is not an exaggeration to suggest that these complex challenges pose serious threats to children’s ability to thrive and reach their full potential as adults—and unfortunately, across a number of indices the trends are discouraging.

Data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health, a survey of the parents of children under age 18, provides estimates of the national- and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders in children and those who accessed treatment. The report found that 16.5% of children have at least one mental health disorder and that 49% of these children are not receiving treatment.3 The prevalence of children with one or more mental health diagnoses who were not receiving treatment varied widely across states, with Washington, D.C., at 29.5% and North Carolina at 72.2%.3 This study and others raised the alarm about the increased prevalence of mental health disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults, even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, across the nation pediatric patients with behavioral health needs are presenting to emergency departments (EDs) in growing numbers—not only for acute psychiatric emergencies, but also for more routine care. Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey of ED visits reflected a 28% increase in behavioral health visits for children aged 6–24 from 2011 to 2015.4 Potential factors include the limited availability of providers and behavioral health treatment options and access to medical care and insurance coverage, particularly for marginalized populations. For many families and in many locales, EDs have become the frontline providers of pediatric behavioral health care.

Pandemic Impact

As noted, a youth mental health crisis was already simmering when COVID-19 was declared a worldwide public health emergency in March 2020. The onset of the pandemic led to immediate and profound disruptions to young people’s lives, including abrupt school closings, compulsory quarantine, social isolation, loss of adult mentors, disruption of many school-based support services, family stress, fear of illness, financial challenges, and exposure to traumatic events. The pandemic exacerbated an already high level of distress among youth and tested the behavioral health systems across the nation, which were already struggling due to a lack of investment in the workforce, treatment programs, infrastructure, and a public health strategy.

A meta-analysis of 29 global studies measuring the prevalence of increased depression and anxiety symptoms among 80,879 youth reported that during the first year of the pandemic, the pooled prevalence estimate for increased depression symptoms was 25.2%, compared to 12.9% pre-pandemic; the estimate for increased anxiety symptoms was 20.5%, compared to 11.6% pre-pandemic.5 These results suggest that the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic.

Several studies conducted during the first year of the pandemic showed an increase in the proportion of ED visits for youth with mental health-related problems. For example, Bommersbach and coauthors examined cross-sectional data from 2011 to 2020 from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey of mental health visits to EDs for young people aged 6–24 years. This study showed that while the overall total number of pediatric ED visits had not changed substantially, the number of ED visits for mental health difficulties doubled and increased five-fold for suicide-related behaviors.6 In addition, less than 20% of those ED visits involved a behavioral health expert.6 The National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief (2023) notes that the rate of death by suicide from 2002 through 2021 increased for both males and females aged 10–25 years.7 The CDC’s 2001–2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report, which collects data every two years from a nationally representative sample of high school students across the United States, found that in 2021, 22% of high school students seriously considered attempting suicide, with 10% attempting one or more times during the past year.8 Black students were more likely to attempt suicide than White, Asian, or Hispanic students.

Post-Pandemic State of Behavioral Health

In 2019, suicide was the leading cause of death for children in North Carolina in the 10–14 age group. Then in 2021, a startling number of children (N = 67) in North Carolina died by suicide between ages 0 and 18.9 The death rates of those aged 0–17 by use of firearms from 2020 to 2021 in North Carolina increased by 231.3%.9 National surveys have shown that children from underrepresented groups who experience significant discrimination also report worse mental health experiences. For example, in North Carolina LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to attempt suicide as compared to heterosexual groups.10

With the continued increase of youth presenting across the nation to EDs for behavioral health needs, health care systems have struggled to manage the care coordination needed by these children, which has led to the increased “boarding” time for children in the emergency departments.11 The definition of boarding by the Joint Commission is the “practice of holding patients in the emergency department or temporary location for four hours or more after the decision to admit or transfer has been made”.12 The evidence suggests that the boarding care phase for children with behavioral health illnesses is difficult for not only for children and their families but also for the health care providers working in EDs. There are several problems that occur while a child waits for the next level of care in the ED. These include minimal psychiatric treatment provided apart from safety supervision and being held in a non-therapeutic space with the inability to go outside. Children and families report experiencing this as being held in a prison-like environment with disjointed communications from provider teams, not to mention the disruptions in educational and social development.

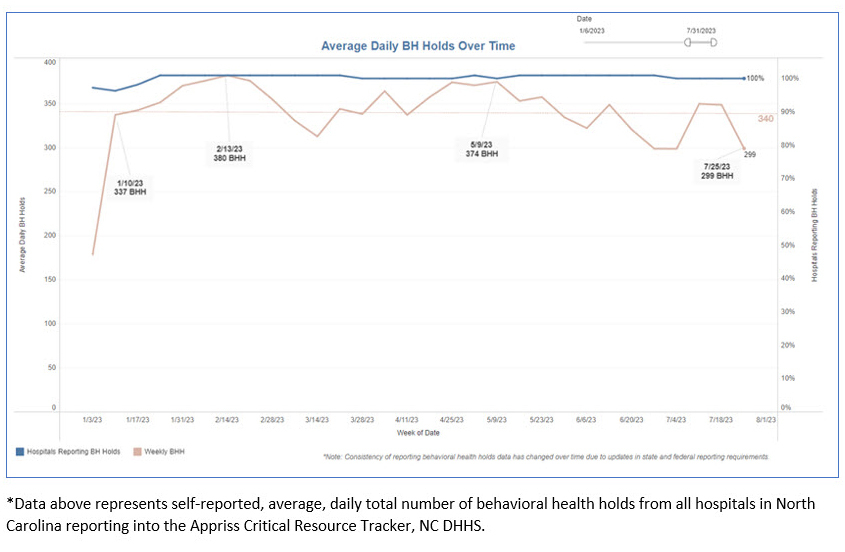

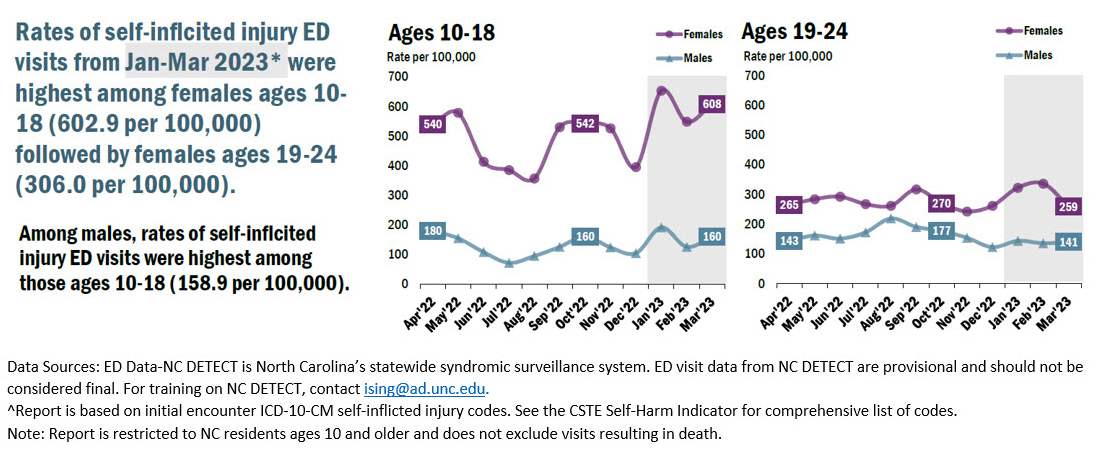

Unfortunately, though North Carolina is avidly building its behavioral health data infrastructure, our state is not immune to these national trends. Early data from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) reveal a terrifying picture: as can be seen in Figure 1, the average 2023 daily statewide total for behavioral health holds has been 340 individuals. Soon the state will be able to determine how many of those individuals are youth, but current estimates are that at least 50 youth are living in EDs across North Carolina every day. We also know from statewide surveillance data that rates of self-inflicted injury ED visits from October to December 2022 were highest among females aged 10–18.13 This is unfortunately a trend that has only continued into 2023 (Figure 2).13

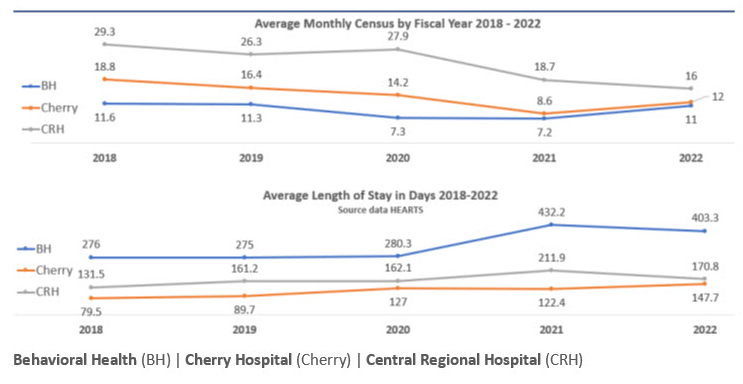

Despite the clear evidence of need for youth inpatient psychiatric care, due to the incredible workforce challenges born out of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state is operating fewer youth inpatient beds (Figure 3) and seeing longer lengths of stay.

Taken together, these data demonstrate a stark picture for North Carolina youth in behavioral health crisis. In March 2023, Governor Roy Cooper, in partnership with NCDHHS, released a proposal for a historic investment in North Carolina’s behavioral health system. Among other initiatives, this proposal included increasing Medicaid reimbursement for all behavioral health care services to improve access to treatment and new specialized programs for youth.14 At the time of writing this article, the North Carolina General Assembly has not yet passed a budget and we are hopeful that the final budget will include these recommendations.

The Path Forward

In response to the youth behavioral health crisis in North Carolina, academic health care systems across the state have employed a number of strategies to meet the needs of the children and adolescents in our state.

UNC Health

UNC Health has developed multiple new large-scale initiatives to improve the care provided to children and adolescents. First, UNC Health has partnered with NCDHHS to open a new, specialized youth behavioral health hospital in fall 2023.15 The new hospital is in Butner, North Carolina, in a facility that was previously run by the state as an adult alcohol and drug abuse treatment center. The critical partnership between two state entities, NCDHHS and UNC Health, will provide greatly needed inpatient psychiatric care for youth and will serve as a model that can be exported across the state to meet this critical need. UNC School of Medicine faculty will be providing specialized care to children and adolescents at this new facility.

The second major initiative is the UNC Health Acute Telepsychiatry Service, which was launched in July 2022 and is a collaboration between UNC Health Virtual Care Services and the UNC School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry.16 This program is a significant investment by UNC Health to address the youth behavioral health crisis across its provider entities, especially those located in rural areas where access to behavioral health care is poor. This new program provides virtual psychiatric consultation by UNC faculty to UNC Health EDs and inpatient medical/surgical units at seven locations. In the first year of operation, more than 1,300 patients received a total of 2,048 consults and 29% of these consults were conducted on children and adolescents presenting to EDs across the state.16

East Carolina University Health (ECUH)

In response to the youth behavioral health crisis ECUH expanded the NC-STeP adult program in February 2023 to include services for children and adolescents in a three-year partnership with United Health Foundation.17 This expanded program will provide behavioral health services for children in the primary care setting.17,18

Currently ECUH does not have an inpatient behavioral health facility to provide acute care services when a child presents to the ED. There are limited options for other regional facilities that have the availability, and many do not accept children under age 12. Another challenge is that all these regional facilities are more than an hour away from the ECUH region, which leads to hardship for the child and family. However, through a partnership with Acadia Healthcare, ECUH will be building a 144-bed inpatient psychiatric hospital that includes 24 inpatient beds for children and adolescents suffering from behavioral health disorders.19

Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist

The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (CAP) division of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist is engaged in several clinical and educational initiatives to address the mental health crisis. The emphasis is to provide more integrated care for youth mental health along with increasing the capacity for outpatient care, particularly to underserved populations. Despite decreases in funding streams, the division continues to exceed targets for serving the youth Medicaid population in Stokes and Forsyth counties; in Forsyth County, for example, the funded target was 80 individual patients with 660 visits, and the actuals were 223 individual patients and 956 visits during FY 2022–2023 (unpublished data extracted from Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Epic, July 2023). CAP expanded its integrated care in partnership with pediatric colleagues to support treatment of children and adolescents with behavioral health issues and thus expand access to care.20 A faculty psychiatrist and a CAP fellow travel to the local community health center (Downtown Health Plaza in Winston-Salem) one half day per week to perform assessments and provide treatment recommendations. The CAP fellows rotate in clinics in adolescent medicine—the gender care clinic and eating disorders clinic in the Department of Pediatrics—and the Pediatric Neurology clinic to evaluate patients and provide education to providers caring for them, since these populations are at statistically greater risk of experiencing psychiatric disorders.

Duke University Health System (DUHS)

The Duke Division of Child & Family Mental Health & Community Psychiatry created several programs that began as pilots in 2017. Fortunately, these programs continued to successfully grow and develop beyond the pilot phase and were available to provide crucial behavioral health services needed by children and their families during and after the pandemic. The first of these two programs is the Duke Children’s Evaluation Center (DCEC), which serves as both a triage center and an outpatient clinic for pediatric patients with behavioral health difficulties. This program was created to ensure continuity of care for children who present to the ED with behavioral health problems who are then discharged to outpatient treatment. The DCEC serves as an access point for children with behavioral health needs throughout the health system and especially those who may be at higher risk for returning to the ED. The children are seen by a multidisciplinary team that consists of a child psychiatrist, nurse practitioner, social workers, and trainees. On average there are 2500 visits, approximately half new visits and 30% from the ED, seen each year; during the pandemic the DCEC team provided additional innovative supports for the community. This included NC-PAL, a behavioral health consultation line that allowed primary care providers to send in consult questions that were responded to within 48 hours.21

Further, as part of the state’s pandemic response the NC-PAL team worked with NCDHHS to deploy a CDC-funded school staff intervention for over 100 schools across North Carolina. From January 2023 to June 2023, the team worked with over 200 school personnel from 32 counties to provide mental health education and support sessions.22 School personnel indicated that participation in the program improved their confidence in helping students, parents, and teachers around pediatric mental health conditions; in addition, over 70% indicated that participation in the program had improved their ability to recognize and address their own burnout.22

Conclusion

North Carolina’s public health and health care systems are highly invested in addressing the youth behavioral health crisis and bringing specialized child and adolescent psychiatric care both locally and to underserved settings across North Carolina. There remains a great need for building more behavioral health services, growing the workforce, and creating environments where children and adolescents can thrive.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of interests. The authors are representatives of several of the systems and programs mentioned within the article. The work does not necessarily reflect the views of the systems and programs mentioned. No further interests were disclosed.

We would like to thank Ms. Angela Garrett for her assistance with manuscript review and preparation. Also, we thank our behavioral health colleagues across the state who are dedicated to caring for children and families and their behavioral health needs. It is an honor to serve our children and families in North Carolina.