Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association have declared a national emergency in adolescent mental health,1 while the US Surgeon General has made youth mental health a key priority.2 Drivers of mental health needs among youth are multifactorial. Mental health is closely linked to physical health3 and is also influenced by social determinants of health, such as poverty, racism, and geography,2 all of which have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.4

Unmet physical, mental, and social health needs influence a child’s ability to thrive academically. In school settings, these may manifest as behavioral disruption or disengagement leading to violence, suspensions, and drop-outs.5 Other students may suffer silently, without demonstrating overt symptoms that impact their educational performance.6 These unmet needs are also key drivers of school absenteeism.7

North Carolina’s Youth Mental Health Crisis

In North Carolina, 1 in 5 adolescents has seriously considered attempting suicide, 1 in 10 has made a suicide attempt,8 and more than 1 in 10 children aged 3–17 has a diagnosis of anxiety or depression.9 The 2023 North Carolina Child Health Report Card gave the state an ‘F’ for child mental health, citing that these trends are worsening.10 North Carolina’s health and education systems are failing to meet the increased mental health needs of children. In this state, only 28% of children with a diagnosed mental or behavioral need receive care from a specialized mental health care provider.11 The state ranks 46th nationally in providing appropriate in-school supports and accommodations for children with mental health needs.9

North Carolina faces a critical shortage of mental health providers: the state has only 32% of the recommended number of child and adolescent psychiatrists (CAPs) for the population and they are concentrated in urban counties.12 Of the 100 counties in North Carolina, 61 have no CAPs at all.12 This results in long travel distances and waitlists to see a mental health provider, particularly in rural settings.13 Pediatric primary care providers may be able to prescribe medications and support families with behavioral, social, and educational difficulties. However, the majority of pediatricians report feeling inadequately trained to provide the care that a mental health specialist can provide.14 Additionally, there is a shortage of providers who can do therapy, so youth are often waiting months to establish care with a therapist.15 Barriers to mental health care include high costs and low reimbursement rates.14 These barriers, closely intertwined with social determinants of health, disproportionately impact low-income, minority, and rural communities as well as children with special health care needs.14

A School-based Solution to Address Barriers in Access to Mental Health

A recent systematic review of policy levers to promote access and utilization of children’s mental health services demonstrated that school-based models of delivering mental health services are associated with higher utilization and higher satisfaction compared to community-based services.16 These models also improve access to mental health services in rural settings, decreasing barriers such as transportation and time off from work for caregivers.13,14

Specialized Instructional Support Personnel

An integrated, school-based care model is a promising solution for improving health and education outcomes among North Carolina’s youth. This can take the shape of a multidisciplinary team consisting of school counselors, social workers, psychologists, and nurses who work collaboratively to deliver a range of services that address individual and population health needs while reducing barriers in access to care.

SISP include four main types of school-based provider roles, each making a unique contribution to student health:

Counselors develop, implement, and evaluate school-wide programming aimed to improve school climate and connectedness. They provide individual and group counseling, facilitate conflict resolution, help students develop social skills, and offer college and career guidance.

Social workers work closely with families, teachers, and the community to facilitate access to resources addressing needs that may be affecting students’ academic performance, such as housing and nutrition. Some social workers are qualified to diagnose mental health conditions and provide therapeutic interventions.

Psychologists primarily focus on students’ mental health and educational achievement. In addition to targeted individual behavioral health services, they conduct assessments to identify students with learning difficulties and unique behavioral needs, and they work closely with the student, family, and teachers to develop individualized plans for instructional and behavioral support in the classroom. They also help to develop school behavioral health practices and systemic response protocols, such as risk and threat assessments.

Nurses identify and address acute health needs, manage chronic health conditions, provide health education, and develop school health policies to promote healthy school environments.

In addition to student-facing services, SISP provide in-service training for teachers and staff, offer parent education, and facilitate community collaboration efforts.14 Overlapping roles of SISP include individual or group counseling for students, fostering positive school climate, behavioral intervention strategies, performing suicide and threat assessments, and crisis prevention services.17

Evidence for SISP Effectiveness

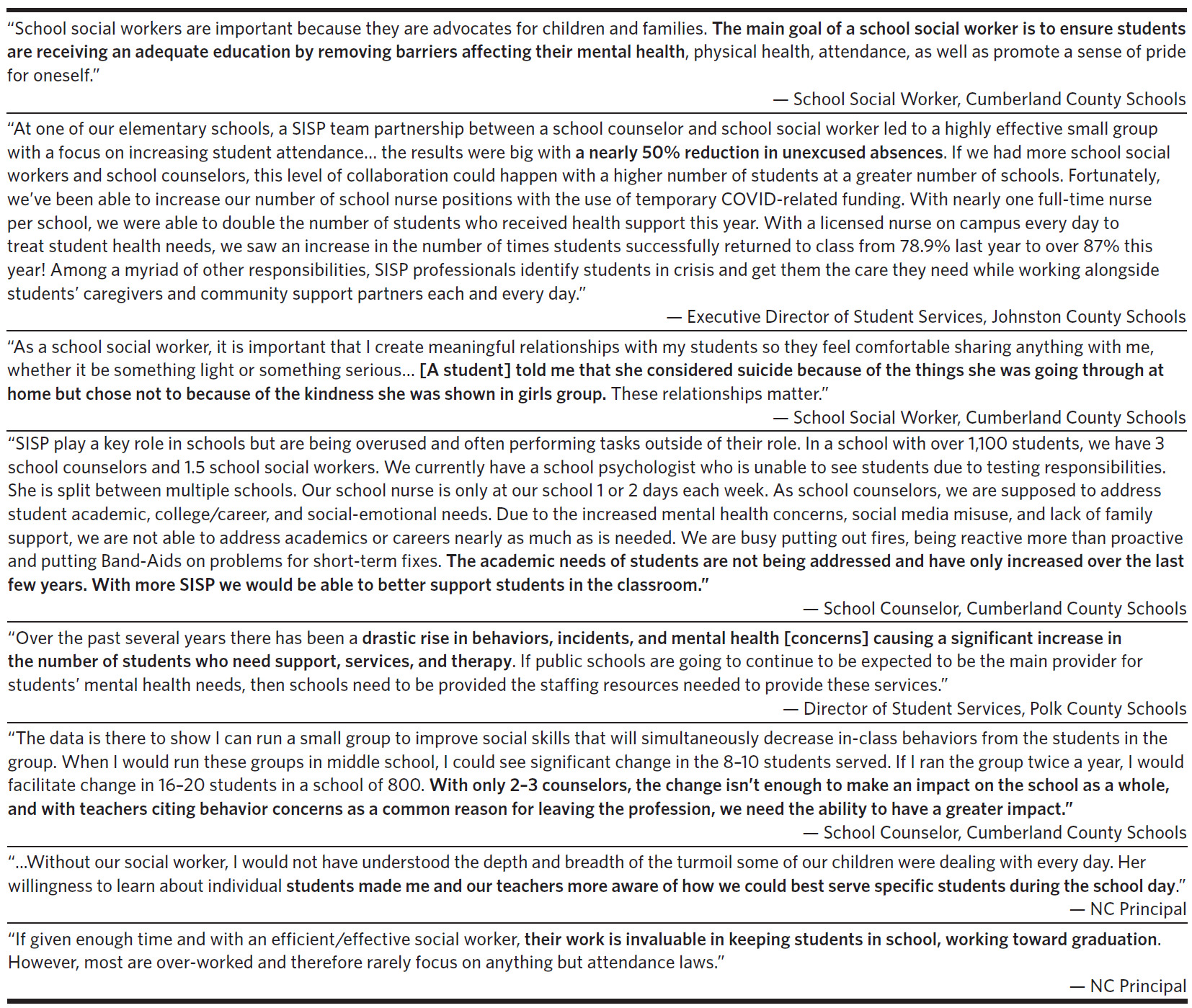

There is a growing body of evidence that SISP are a cost-effective way to improve both health-related and educational outcomes at the individual and population level. In addition to the literature, North Carolina school personnel verbalized the value of SISP to the authors, with quotes in Table 1.

Improved Physical and Mental Health Outcomes

School nurses are well-positioned to provide both individual and population health services and reduce barriers in access to health care. They play a critical role in identifying, addressing, and coordinating the health care needs of children through health education, policies to promote health and safety, management and monitoring of chronic health conditions, evaluation and treatment of non-severe acute conditions, and identification and referral of more serious health concerns to higher levels of care.18 School-based health providers increase return-to-class rates compared to unlicensed personnel who are more likely to unnecessarily send children home or to an acute-care facility, resulting in loss of instructional time and unnecessary health care spending.18,19

School psychologists and clinical social workers provide early identification and management of mental health needs, which can prevent more costly and intensive interventions, such as psychiatric hospitalization.20 Management of mental health conditions also helps improve physical health outcomes.21 School-based mental health specialists are shown to decrease adolescent cocaine use by 45.8%, marijuana use by 11.5%, tobacco use by 10.7%, and binge drinking by 8%.22 In addition, cost-effectiveness studies have shown that school-based mental health and substance use prevention programs can save $11 to $18 per dollar that is invested.22,23

Improved Educational Outcomes

With expertise in mental health, behavior management, and social dynamics, school social workers, counselors, and psychologists are equipped to promote positive school climate and social-emotional learning (SEL), which improves students’ sense of community and belonging.24 Positive school climate is associated with prevention of interpersonal conflict by 80% and health benefits lasting into adulthood.25 These providers are also trained to identify and de-escalate interpersonal conflict through trauma-informed interventions.26 These methods are more effective than punitive and exclusionary discipline practices, which are associated with criminalization of child behavior and increased rates of youth incarceration and juvenile justice system involvement.27

The presence of SISP improves the school environment and promotes a number of positive educational outcomes. Policies that improve ratios of school counselors to students have been shown to decrease school physical aggression and absenteeism while increasing instructional time and improving academic performance.28,29 School counselors have been shown to decrease suspensions by 22% and increase college attendance by 8% among students with below-average test scores.28,29 A study that measured the impact of adding a counselor to a school found that this is twice as effective as hiring an additional teacher to improve academic achievement.26 School psychologists who work in environments with recommended staff-to-student ratios have been shown to improve student focus and motivation for learning, decrease drop-out rates and absenteeism, and improve school safety.30 Similarly, school social workers are associated with improved attendance and three-times-higher graduation rates.31 Teachers recognize the value of SISP: according to a survey, teachers valued having access to more school counselors and nurses over a 10% pay raise or a reduction in class size.32

Policies to Support SISP and Student Health

Invest in Development, Recruitment, and Retention of SISP

North Carolina currently ranks 47th in the nation in total dollars of spending per student and 50th in funding effort (percent of GDP toward education).33 As North Carolina school districts approach the end of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds via the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act in 2024, North Carolina schools will lose more than 10% of their current below-adequate funding.34

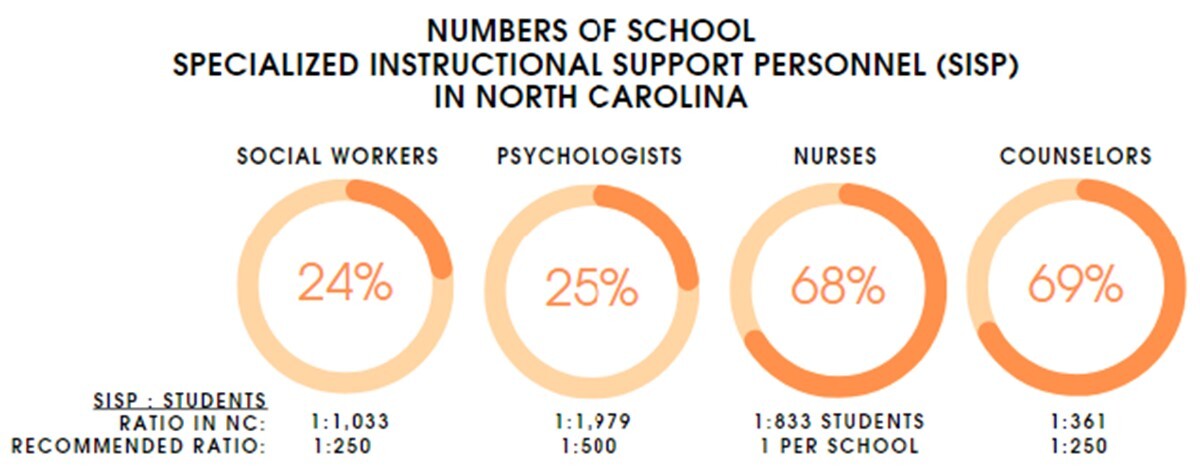

Moreover, North Carolina schools are significantly understaffed, with lower-than-recommended ratios of each SISP provider type (Figure 1).35 School social workers and psychologists are in particularly low supply, with only about 25% of the recommended number to serve the needs of North Carolina students (unpublished data, Department of Public Instruction Business Office, 2023).

Investments in SISP that have been endorsed by the North Carolina State Board of Education, North Carolina State Superintendent, North Carolina Center for Safer Schools, North Carolina Parent Teacher Association (NCPTA), and the North Carolina Child Fatality Task Force include: increased funding for education, including adequate budget allocation to hire SISP at recommended ratios; development of training programs for each SISP provider type to increase the workforce; and competitive salaries to improve recruitment and retention of SISP.5,36,37

The North Carolina State Board of Education has requested $100 million in the 2023–2025 biennial budget for 1000 more school-based nurses and social workers, $5 million for a school psychologist internship program, and $10 million to provider master’s level pay for social workers.38 This would be a tremendous start to developing sustainable SISP programs to support the health and social needs of children across the state.

Medicaid Reimbursement for School-based Services Provided by SISP

While many school-based services provided by SISP are eligible for Medicaid reimbursement, not all are. Expanding Medicaid eligibility for school-based services to include psychotherapy for crisis and substance use cessation counseling and screening for mental health conditions would help provide federal funding for the work that SISP are already performing, currently without reimbursement.

Many schools do not have the technical bandwidth to handle the administrative burden associated with Medicaid reimbursement. As a result, claims for many eligible services that SISP provide are not submitted to Medicaid for reimbursement, and the cost for these services falls on the school budget. Technical assistance to schools would greatly facilitate Medicaid reimbursement claims and provide federal funding outside of the school budget for services provided by SISP. To that end, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance in 2023 to significantly expand access to health and behavioral services in schools by reducing administrative burden associated with Medicaid reimbursement.39 Facilitating Medicaid reimbursement in these ways has been demonstrated to provide a significant influx of federal funding for services provided by SISP: after passing legislation to facilitate school-based Medicaid reimbursement, the state of Michigan doubled the amount of school behavioral health providers and anticipates an increase of $14 million in federal funding from school psychologists alone.40

Conclusion

Given the many barriers that North Carolina children face in accessing mental health treatment, including severe shortages in child and adolescent psychiatrists, there is an urgent need to look toward alternative solutions. SISP provide an integrated, school-based approach to identifying and addressing unmet health and social needs and reduce barriers in access to care, particularly in rural settings. North Carolina could revolutionize the way we address the mental health needs of our children and foster a healthier, more resilient future generation of North Carolinians prioritizing funding and policy measures to ensure sustainable support for these essential professionals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the school social workers and counselors from Cumberland County Schools, Amanda H. Allen, PhD, from Johnson County Schools, and Toni Haley from Polk County Schools, who provided quotes about their experiences relating to SISP. We would also like to acknowledge Pachovia Lovett, MSW, school social work consultant from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, for sharing helpful resources relating to SISP.

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.