Introduction

Nutrition security refers to consistent, equitable access to a sufficient, safe, and nutritious food supply to optimize health and well-being and meet the food preferences of all individuals.1,2 Food security, on the other hand, primarily focuses on the availability, affordability, and accessibility of sufficient amounts of food on a consistent basis. While nutrition security encompasses food security, it emphasizes the overall quality and nutritional value of the food.3

In North Carolina, 17% of households with children experience food insecurity compared to 12.5% nationally.3,4 Hispanic and Black households with children are three and four times more likely, respectively, to experience food insecurity compared to White households.3 Additional characteristics associated with higher rates of food insecurity include households with children under age six, those with female heads of households, and those living in urban areas.3 Families experiencing poverty and low-income families who do not meet the federal definition of poverty also have high rates of food insecurity.3 While the causes are multifaceted, poverty and structural racism—along with their downstream consequences—are root sources of food and nutrition insecurity.

Healthy, adequate nutrition within the first 1000 days of life is particularly important for neurodevelopment and lifelong health, and health care providers who treat young children are uniquely positioned to improve a child’s life course by connecting families to food and nutrition support programs. Childhood food insecurity is associated with adverse outcomes, including negative developmental and academic trajectories, poor mental and physical health, and increased hospitalizations and utilization of the emergency department.5–8 Food insecurity is also associated with approximately $52.9 billion annually in health care costs among adults and children in the United States and $1.7 billion in North Carolina.9

Policymakers and payers are increasingly implementing recommendations to promote food and nutrition insecurity screening and interventions within clinical settings. Multiple large-scale national standards, regulations, and quality initiatives are also being implemented from organizations including the National Commission for Quality Assurance Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set program, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the Joint Commission, all of which require health systems to collect data on patients’ food security status.10 Additionally, the National Academies of Medicine published a report on successfully integrating social care—including food insecurity—into health care settings, including creating interprofessional teams, advancing health information technology, and aligning payment models.11

North Carolina has been a nationwide leader in testing innovative programs that promote the integration of food insecurity screening and intervention into health systems. Since 2018 our state has actively prioritized addressing childhood food and nutrition insecurity through initiatives like the North Carolina Early Childhood Action Plan (ECAP), universal food insecurity screening for all Medicaid beneficiaries, and efforts such as NCCARE360—the statewide direct referral platform that connects health care and human services organizations—to increase coordination across health systems and community-based organizations (CBOs) that provide food and nutrition supports.

Challenges

National Standards

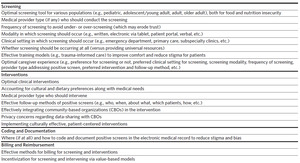

Despite emerging national standards around food insecurity, little evidence-based guidance has been provided by regulatory bodies for how to effectively conduct screening and interventions for food and nutrition insecurity in pediatric clinical settings. Additionally, best practices for coding and documentation in patients’ charts, along with billing and payer reimbursement, remain unclear. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Food Research & Action Center have released a toolkit for pediatricians, and some research examining effective methods for screening and interventions exists, more research is needed to better guide implementation and practice (Table 1).12–15

Staff and Community-based Organization Capacity

Given the differences between clinic and health care system workflows, along with unprecedented levels of medical provider turnover during COVID-19 and beyond, staff capacity to screen for and address food and nutrition insecurity remains a challenge.16,17 Expanding positions for patient navigators, community health workers, or social workers who effectively support connection of patients to community resources is vital for developing sustainable systems to address food and nutrition insecurity identified in clinical settings.18 Further, for CBOs receiving referrals from health care systems, additional infrastructure, personnel, and funding may be necessary to accommodate need. Health care/community partnerships could promote innovations in addressing food and nutrition security by harnessing the strengths of community partners through dedicated financial support; these partnerships can also promote community trust.19 As medicine increasingly transitions to a value-based care model in which providers are financially accountable for and incentivized by improving patient outcomes and metrics (e.g., percent of patients screened), CBOs will need to be thoughtfully incorporated into these models.20,21

Shared Data Systems and Privacy

The federal nutrition programs (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP] and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]; Medicaid; health care systems; and CBOs) each utilize different data systems to manage their clients and patients. These data systems are often siloed and lack the ability to communicate with one another, potentially leading to lower and more burdensome program enrollment, duplication of efforts, and miscommunication. This lack of information-sharing creates challenges in recognizing who within a family is receiving which benefits.22 To promote cross-sector collaboration, more effectively address food and nutrition insecurity, and provide whole-person care, shared data systems will need to be created and an investment in technology should be made while also being mindful of privacy protections.23 For example, several states have pilot tested data-matching between SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid data and conducting text-message outreach to eligible families. This approach showed promise in reaching WIC-eligible non-participants.24 Data-sharing regulations through the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) present challenges for cross-sector communication, and informed patient consent to support shared decision-making will be necessary to promote trust. Furthermore, best practices for documenting food and nutrition insecurity in the electronic health record to minimize stigma and bias are necessary.

Opportunities and Potential Policy Solutions

North Carolina is well-positioned to support collaborations across sectors to address food and nutrition insecurity among households with children. The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) has established a vision “that all children are healthy and thrive in safe, stable, and nurturing families, schools and communities,” of which addressing food and nutrition security is a key component.4 To promote this vision, NCDHHS launched the Division of Child and Family Well-Being in 2022. The division brings together multiple previously siloed programs that promote whole-child health, including SNAP and WIC. In 2023, NCDHHS created the State Action Plan for Nutrition Security with three priority areas: 1) increase the reach of NCDHHS’s nutrition programs, 2) build connections between health care and nutrition supports, and 3) increase breastfeeding support and rates. Through many established and upcoming innovations, some of which are detailed in the following paragraphs, NCDHHS’s goal is to decrease the overall rate of food insecurity in the state by 0.9% by December 2024.4 The North Carolina ECAP also includes the child-specific goal of decreasing the rate of households with children experiencing food insecurity by 3.4% by 2025.4

Improving Access to Nutrition Assistance Programs Through Data-Sharing Initiatives

To reach the goal of increasing enrollment in nutrition programs, NCDHHS has matched enrollment data across SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid to identify participants and households enrolled in at least one program and eligible for but not enrolled in other programs. Although federal nutrition programs mitigate poverty and food insecurity, many people who are eligible do not enroll. Various initiatives are being developed and implemented to assess effective ways to utilize this cross-enrollment data to reach potentially eligible patients through methods, such as text messages or phone calls from care coordinators.

Additional data-sharing solutions also hold promise. In 2015, the North Carolina General Assembly created the North Carolina Health Information Exchange (HIE) Authority to oversee NC HealthConnex, a secure electronic network that facilitates communication between health care providers, enabling voluntary access to shared health-related patient data across the state. Like other HIE systems, NC HealthConnex aims to improve health care quality and health outcomes, enhance patient safety, and reduce overall health care costs.25 NC HealthConnex could eventually be utilized to share relevant health data and promote coordination of services across health systems and nutrition programs. For example, HIE systems could facilitate the exchange of child biometric data (height, weight, hemoglobin) between pediatricians and WIC clinics, making it easier for families to enroll in WIC.

Beyond HIEs, states are also expanding and improving online platforms to support streamlined benefit enrollment. As of 2023, 34 states have digital platforms that support enrollment in three or more benefit programs; five states have platforms that support streamlined enrollment across Medicaid, SNAP, WIC, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and Child Care Assistance.26 State investment in this type of integrated benefit enrollment has been shown to positively impact both individual applicants and agency staff through metrics including speed of completing an application, reduced application processing time, and increased approval rates.27

Improving Access to School Meals Through Policy Solutions

Connecting children with meals at school is an evidence-based method for addressing childhood food and nutrition insecurity.28 The United States Department of Agriculture’s National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP) fed an average of 30.1 million (NSLP) and 15.7 million (SBP) children nationwide each day in 2022.29 Two recent initiatives are connecting more North Carolina students to meals at school through the NSLP and SBP. As of school year 2022–2023, North Carolina is one of now 39 states using Medicaid data to identify students who are eligible to receive free or reduced-price meals through the NSLP and BSP and directly enrolling those students without an additional application.30 Launched in 2023, the School Meals for All NC campaign is working to ensure universal school meals are provided to all public school students at no cost to families. Organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Heart Association, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics have joined to support the national Healthy School Meals for All Coalition. Universal school meals in North Carolina have the opportunity to not only reduce childhood food and nutrition insecurity but remove stigma, eliminate school meal debt, and reduce administrative burden while also improving student health and enhancing academic achievement.31

Healthy Opportunities

In 2018, North Carolina was authorized under a Section 1115 Medicaid waiver to implement Healthy Opportunities Pilots to test and evaluate the impact of providing some non-medical interventions through Medicaid, including those aimed at improving food and nutrition security.32 NCDHHS created a pilot fee schedule, and Medicaid funds can be used to pay for select interventions, such as group nutrition classes, food prescription programs, and medically tailored, home-delivered meals. These pilots provide the opportunity to build the capacity of community-based organizations and create infrastructure that bridges services. The pilots are currently operating in three North Carolina regions that include 33 counties and will be rigorously evaluated, with potential to refine and scale effective interventions to additional counties.

Alternative Payment Models

With North Carolina’s transition to Medicaid managed care in 2020, the state required adoption of value-based payment models when contracting with managed care organizations.33 While most of these models have focused primarily on adults, North Carolina is experimenting with child-focused value-based payment through the NC Integrated Care for Kids (NC InCK) Model. NC InCK, which launched in 2022, is 1 of 7 federally funded child-focused health care delivery and payment models. The goal of NC InCK is to transform health care delivery for children with Medicaid through care coordination, holistic identification and mitigation of clinical and non-clinical risk factors, and the development of alternative payment models (APMs) that link payment with meaningful metrics of child health. Health care providers participating in the NC InCK APM are incentivized to provide high-quality care and screen for social risks including food and nutrition security and they receive actionable data on indicators of success.

Conclusion

While many challenges exist in addressing food and nutrition insecurity among households with children in North Carolina, numerous innovative efforts are already underway. The NCDHHS State Action Plan for Nutrition Security provides a roadmap to reducing food and nutrition insecurity.4 Potential policy solutions, such as implementing a universal benefits application, expanding Healthy Opportunities Pilots and NC InCK, and providing universal school meals at no cost to students could be leveraged to support households with children and improve child health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Palakshappa is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL146902. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. The funding organization had no role in manuscript preparation, review, or approval, nor decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure of interests. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.