Introduction

The United States Military Health System (MHS) spends $50 billion annually on health care for 9.6 million active-duty Service Members and retirees and 2 million Service Members’ spouses, military retirees/family members, and dependents. This global network of 425 military medical treatment facilities (MTFs) offers managed care by civilian health care providers.1

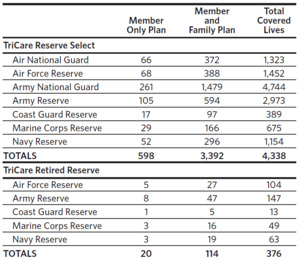

The health and well-being of family members is part of the mission of the MHS, even though operational mission readiness may not recognize family health as essential to Service Members’ ability to focus, be resilient, and serve.2 TriCare Prime is a point-of-service HMO offering treatment coverage by either civilian or military members of TriCare’s provider network. TriCare Standard and Extra plans (PPO) offer fee-for-service coverage with cost-sharing from network providers. Active-duty personnel and their families are eligible to enroll in Prime, while military retirees aged 65 or younger enroll and pay annual enrollment fees. Families of active-duty personnel, activated reservists, military retirees, and their dependents are eligible for the PPO, which offers health care from TriCare-approved providers.3 The purpose of this article is to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to quality TriCare delivery for active and nonactive military and their families in North Carolina. North Carolina’s TriCare Reserve Select (TRS) is used by more than 4,000 members, and TriCare Retired Reserve (TRR) is used by less than 400 members (Table 1).

Strengths

Civilian providers accept TriCare and Medicare at almost the same rate (TriCare at 74% compared to 83% Medicare patients). The Medicare Advantage program and Accountable Care Organizations implement acceptable, risk-adjusted costs to pay health care providers using alternative payment models (APM), episode-based specialty payments, and population-based payments.1 In response to the need for clarifications, TriCare’s fifth-generation (T-5) private-sector purchased care component was implemented in 2023, mandating value-based health care with improved patient outcomes at lower costs.

Weaknesses

TriCare is more rigid with respect to benefits than private health plans, even though similar challenges are found in the civilian sector, such as price increases, more cases of chronic disease, and inadequate access to quality health care services, particularly in rural areas. TriCare’s non-network providers receive reimbursement like Medicare’s, which is lower than payments from private health plans. Even so, primary health care providers (74%) and mental health providers (36%) report accepting new TriCare patients.1 While that is seen as a gain, civilian providers who accept TriCare have continued to be plagued with barriers. Reported reasons for not participating in TriCare and/or Medicare are inadequate reimbursements, insufficient specialty coverage, and lack of knowledge and training about TriCare. Improved reimbursements, specialty coverage, and outreach programs are needed to overcome provider hesitancy. Improving TriCare is beneficial for military members and can complement civilian-based care, particularly through APMs.1

Transitioning from a fee-for-service system to one that is outcomes-based requires providers to utilize systems and tools to measure patient-reported outcomes while implementing new payment systems. Providers receiving value-based payments are at risk if their cost of care exceeds the negotiated rate.1 Furthermore, TriCare’s regional health care providers, which are located in rural areas with fewer beneficiaries, must be able to maintain the same level of care as that found in the TriCare network in Prime Service Areas, which are located near military bases serving a large number of beneficiaries.3

Opportunities

The Defense Health Board (DHB) developed Quadruple Aims for inclusion into health care initiatives to improve readiness by implementing better health and care at lower costs.1 The DHB encouraged TriCare providers to use these aims and value-based suggestions to improve health care from public and private payors and health care organizations. The US Department of Defense (DoD) should assess ease of implementation for TriCare providers using a Central Enrollment System to enable beneficiaries to switch between providers, particularly for mobilization or changes in duty stations; DoD should also use outcomes measurement with regular reporting and monitor results.

With TriCare contracts that began in 2023, the DHB recommended how to best access and determine the top health care strategies from a variety of private, public, and employer-based health plans. To ensure military members are physically and mentally prepared to deploy to disaster areas, MHS must be prepared to provide medical support anytime, anywhere, and in support of military and civilian operations.

Strategies for improving willingness to accept TriCare include increasing rates of provider reimbursements, offering health coverage in specialty areas, and increasing health care providers’ knowledge of TriCare via outreach programs.3 The DHB created an evaluation tool to fast-track TriCare’s shift from fee-for-service payments to a system of increased readiness and improved health care services and well-being at decreased costs. TriCare follows the fee-for-service payment model and recommends using alternative payment methods, such as electronic funds transfers, for TriCare enrollment fees and premiums.1

Currently, in the US Armed Forces, women are 17.2% of the active-duty force (229,933 of 1,333,822 DoD personnel). Active-duty servicewomen (ADSW) need preventive health care along with routine, unique health care services. Prevention includes human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization, cervical cancer screening, mammography, and a variety of birth control methods.2 Providing quality, accessible health care to the women in the military is necessary as this group continues to grow.

Threats

There are many deterrents to private practice clinicians accepting TriCare, such as low reimbursements little knowledge of the plan, and providing access to care in rural areas. Some providers lacked awareness of the TriCare program, reinforcing the importance of educating health care providers by disbursing information regarding TriCare programs.3 TriCare can be more valued by providing education and training sessions, improving reimbursement rates, and focusing on rural TriCare members’ access to care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Charlie Hall, Wounded Warrior, South Carolina; LTC Nicole R. French, Psy.D., Clinical Director, Veterans Bridge Home, Charlotte, North Carolina; and Tracy Spears, B.A., Patient Advocate, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas for their input on this article.

Disclosure of interests

No interests were disclosed.