Telehealth played a crucial role in accessing health care services from the safety of one’s home during the COVID-19 pandemic, with significant increases in telehealth encounters, particularly among those covered by Medicaid.1,2 Telehealth has persisted despite the ending of the federal public health emergency and a gradual return to pre-pandemic policies and behaviors. The question remains: What is the role of telehealth now that the public health emergency has ended? To answer this question, NC Medicaid examined trends in telehealth access and utilization by beneficiaries over time. Discussions with key payor and provider informants shed light on the evolution of telehealth, contextualizing where we have been and where we are going.

NC Medicaid’s Telehealth Journey

In a broad sense, telehealth or telemedicine is commonly understood to be the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support clinical health care without an in-person office visit.3 However, when it comes to clinical coverage policies, telehealth refers to the use of two-way, real-time interactive audio and video to provide care and services when participants are in different physical locations.4 This is separate from ancillary telemedicine services in the form of virtual communications and remote patient monitoring. The former refers to the use of technologies other than video to enable remote evaluation and consultation support between a provider and a beneficiary, or between a provider and another provider. This can include telephone conversations, virtual portal communications (i.e., secure messaging), or store-and-forward telemedicine (i.e., transfer of data from beneficiary to another site for consultation via telecommunication). Remote patient monitoring leverages digital devices to measure and transmit personal health information (e.g., blood pressure) electronically to a provider in another location.

Incorporation of telemedicine and telehealth was increasingly seen in Medicaid policy across the United States even before the COVID-19 pandemic.5 State Medicaid agencies have traditionally had enormous flexibilities in covering telehealth, with significant variation in uptake between states.6 In North Carolina, pre-pandemic telehealth policies included originating-site restrictions that allowed only for telehealth visits between provider sites. However, NC Medicaid took action early in the pandemic to increase access to telehealth for members by expanding telehealth-eligible services and providers, eliminating originating-site restrictions, and making significant investments in telehealth infrastructure.7 Services that made sense to provide via telehalth were also granted coverage and payment parity with in-person care so long as the services met the standard of care and were conducted via HIPAA-compliant technology.8 While coverage for a portion of telehealth services ceased with the ending of the federal public health emergency, many of NC Medicaid’s then-temporary policies were embedded into permanent policy in 2021.

Changes in Beneficiary Telehealth Utilization

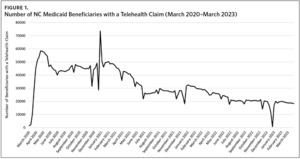

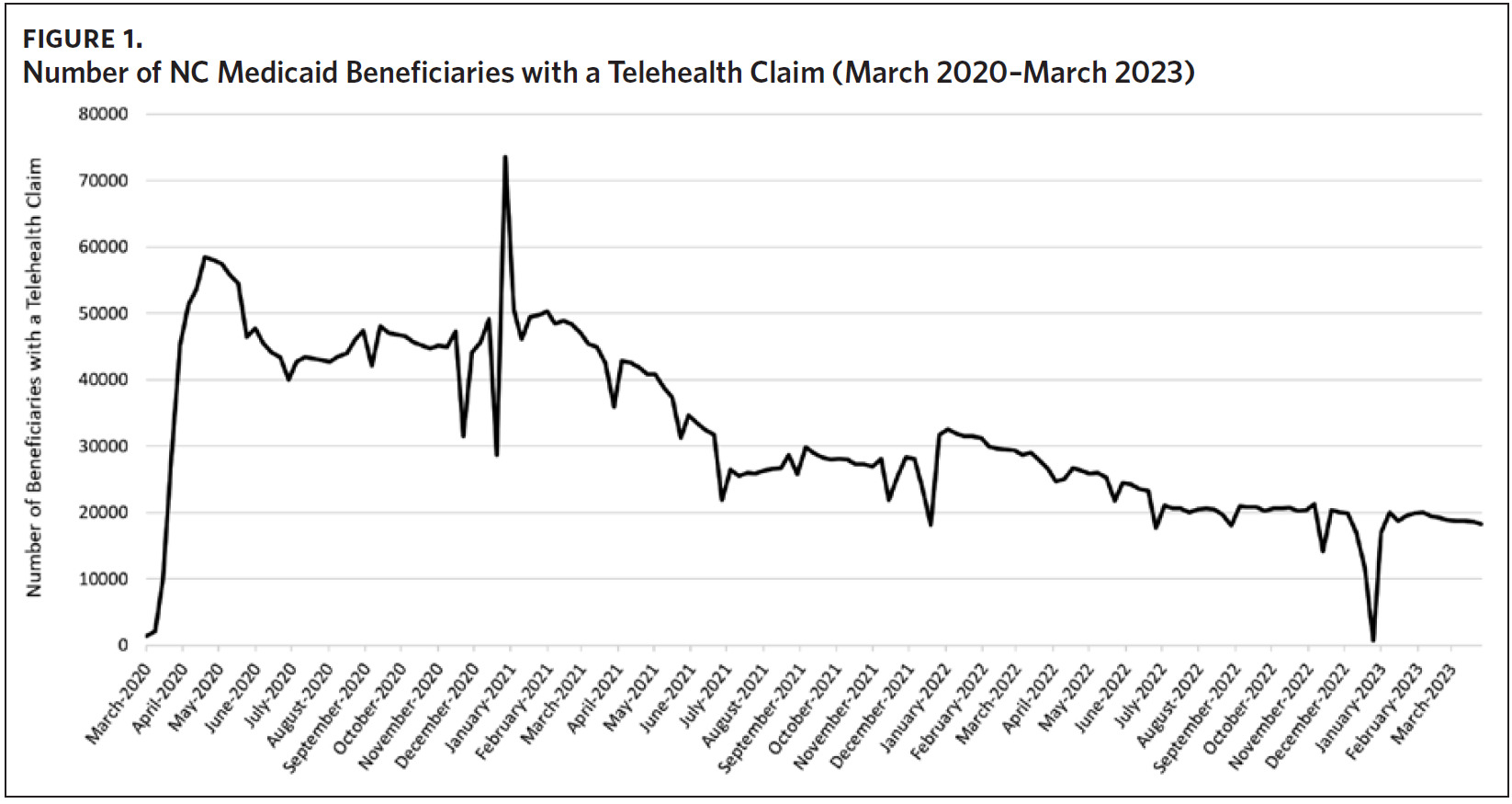

NC Medicaid beneficiaries quickly began utilizing telehealth services in March 2020, with the raw number of beneficiaries with a telehealth claim increasing from 1,404 to 45,123 between the beginning and end of the month (Figure 1).

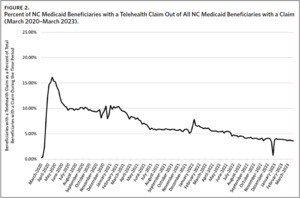

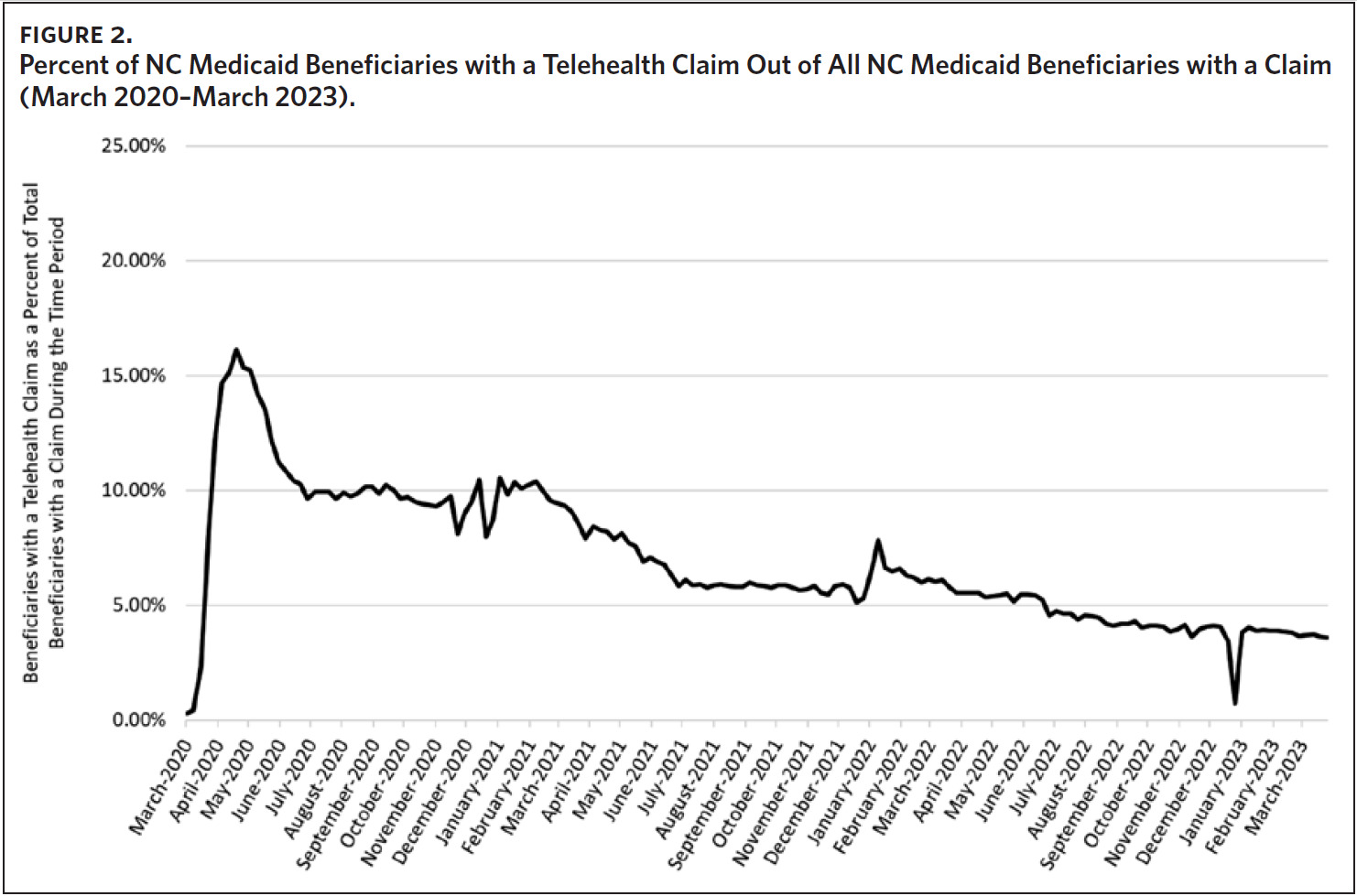

The proportion of beneficiaries receiving care via telemedicine also increased compared to other modalities of care. In the period immediately following Governor Cooper’s statewide stay-at-home order on March 27, 2020, the proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries receiving care via telemedicine climbed as high as 16%, largely because in-person claims were at historic lows (Figure 2).9 The number of beneficiaries using telemedicine then decreased rapidly as North Carolina began moving through the phases of re-opening in the spring of 2020. Factors that may have contributed to decreased utilization include lifting of the state’s stay-at-home order and relaxation of public health emergency conditions such as masking requirements, capacity limits, and social-distancing rules.

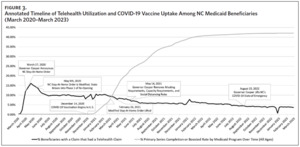

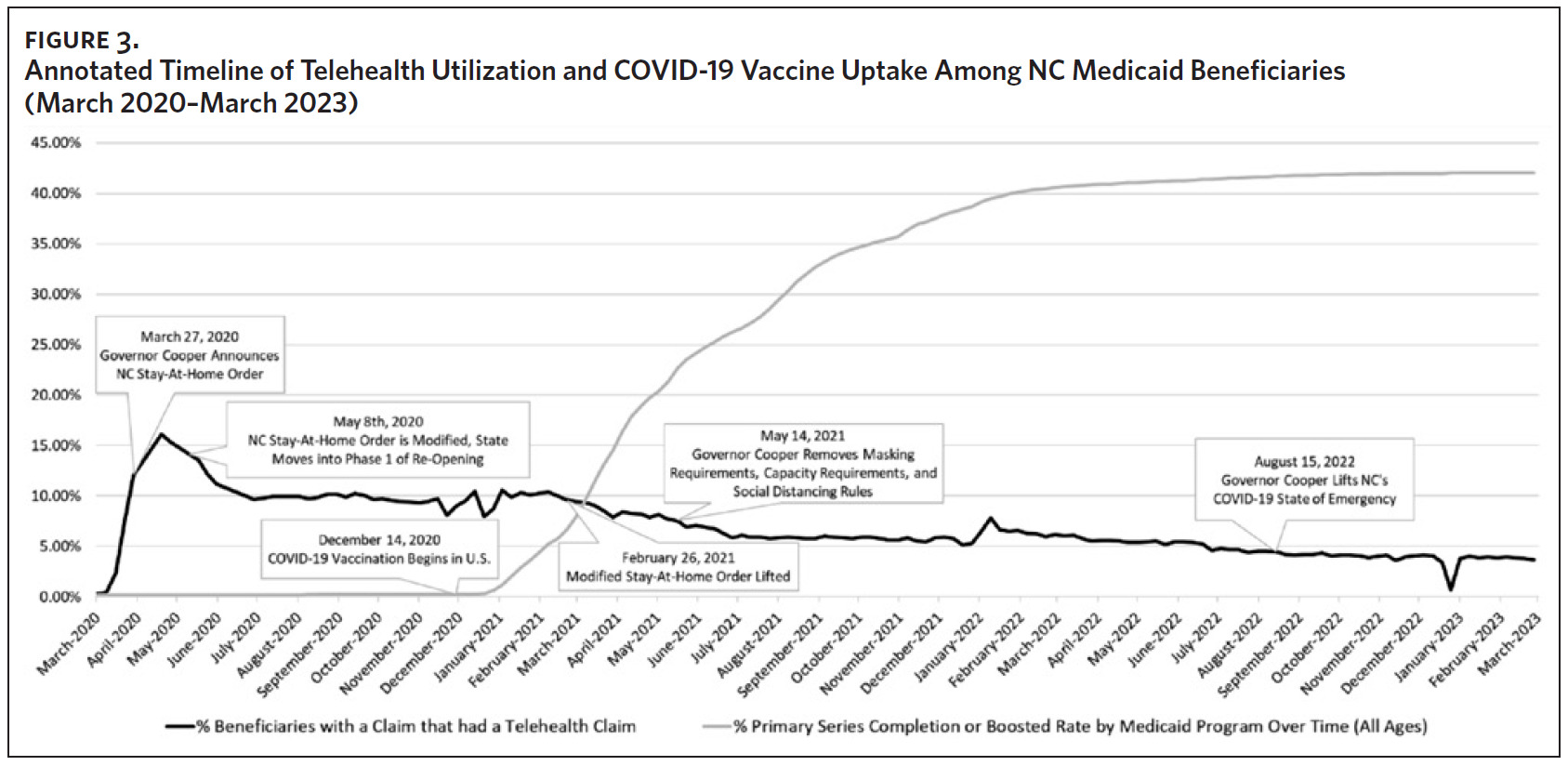

Another pronounced decline in telehealth utilization can be seen in the first half of 2021 (January to July), coinciding with the development and rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine, which officially started in the United States on December 14, 2020.10 By April of 2021, North Carolina had administered over 6.5 million vaccines, with 46.9% of adults being partially vaccinated and 35.1% of adults being fully vaccinated.11 When looking at NC Medicaid beneficiaries specifically, about 20% were fully vaccinated (completed primary series of COVID-19 vaccinations and recommended boosters) by the end of April 2021. However, it is important to note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not recommend COVID-19 vaccines for young children until mid-2022.12 When looking at the relationship between the proportion of beneficiaries vaccinated for COVID-19 and the proportion using telehealth services, a strong negative correlation, r(114) = -.898, p < .00001, is observed for the time period of December 2020 through February 2023 (Figure 3).

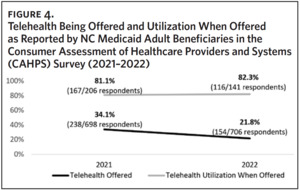

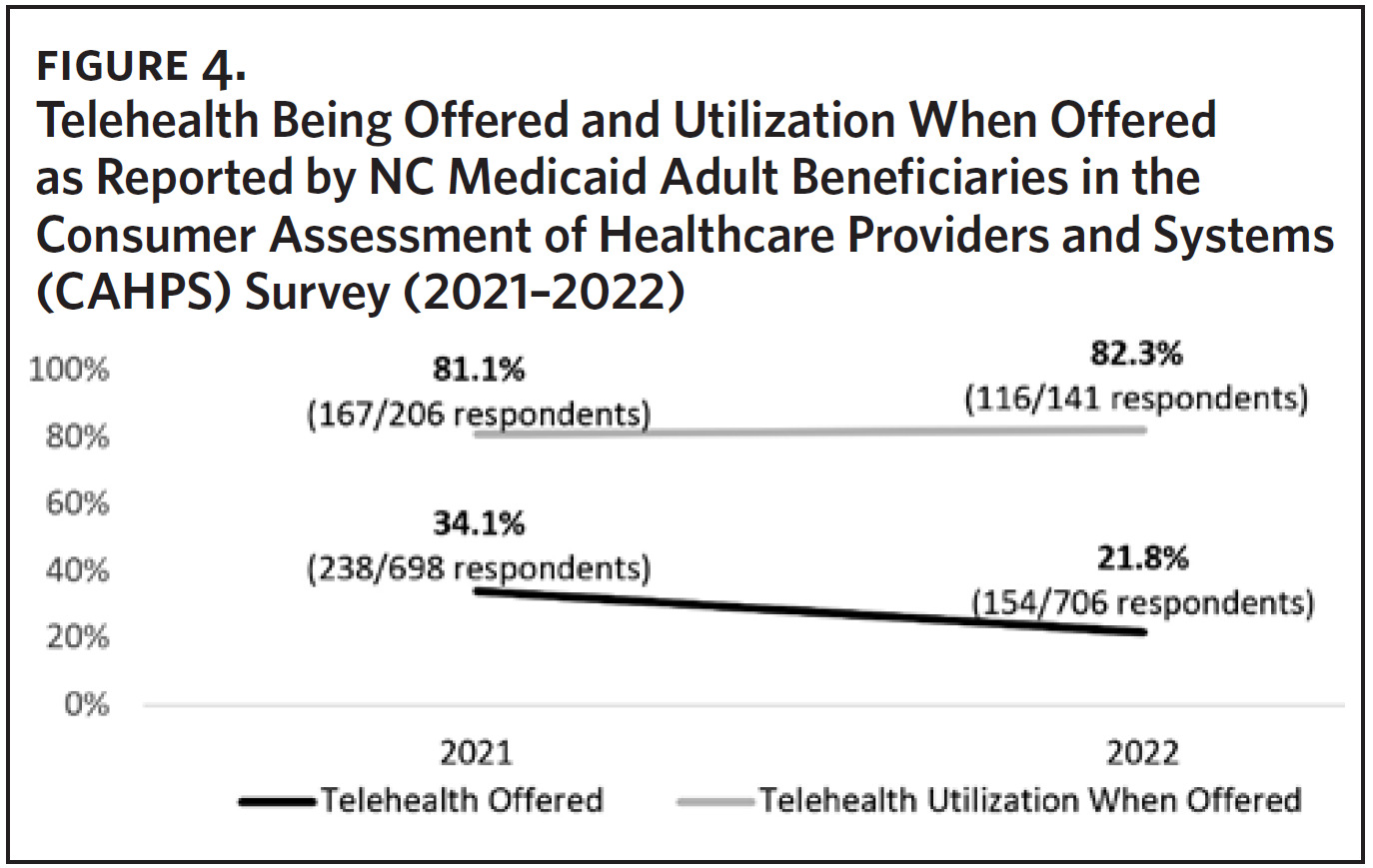

Utilization may also be trending downward as a result of fewer telehealth offerings. Less than a quarter of adult NC Medicaid beneficiaries who responded to the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey reported being offered telehealth instead of an in-person appointment in 2022 (154 out of 706 respondents; 21.8%). This is a 36.1% relative decrease in telehealth offering when compared to 2021 (p = .0002). Despite telehealth being offered less in 2022, utilization when offered slightly increased (Figure 4). This indicates that beneficiaries are still likely to utilize telehealth services even though the risks of the pandemic have decreased and stay-at-home, mask, and social-distancing orders have been lifted.

Numerous studies have shown that patients using telehealth report high satisfaction across dimensions such as experience of care, access, efficiency, and effectiveness.13–15 NC Medicaid beneficiaries reported the same, identifying that they always or usually had their questions answered during a telehealth appointment in 2022 (92 out of 104 respondents; 88.5%). This was an 11.9% relative increase in adult beneficiaries having their questions answered when compared to 2021 (110 out of 141 respondents; 78.0%). This could indicate providers are feeling more accustomed to providing care via telehealth and are able to effectively address health needs/questions. Beneficiaries also expressed increased comfort with how to take care of their health following a telehealth appointment when comparing 2021 to 2022 (119 out of 137 respondents reported “always” or “usually” feeling comfortable in 2021 [86.9%] while 103 out of 116 respondents reported “always” or “usually” feeling comfortable in 2022 [88.8%]).

Technical issues experienced while using telehealth services also remained low from 2021 to 2022, where 91 out of 132 respondents reported no technical issues in 2021 (68.9%) and 63 out of 96 respondents reported no technical issues in 2022 (65.6%). These data suggest that beneficiaries are feeling comfortable accessing health care in a virtual or telephonic setting. Beneficiaries who received telehealth services also rated their overall health care similarly to those who did not utilize telehealth services in 2022 (among those who were offered telehealth and utilized, 78 out of 101 respondents rated their overall health care as positive [77.2%] and among those who were offered telehealth and did not utilize, 12 out of 16 respondents rated their overall health care 8–10 [75.0%]). This further supports that telehealth as a modality of care can present a unique opportunity without compromising patient satisfaction.

Use of Telehealth in the Behavioral Health Space

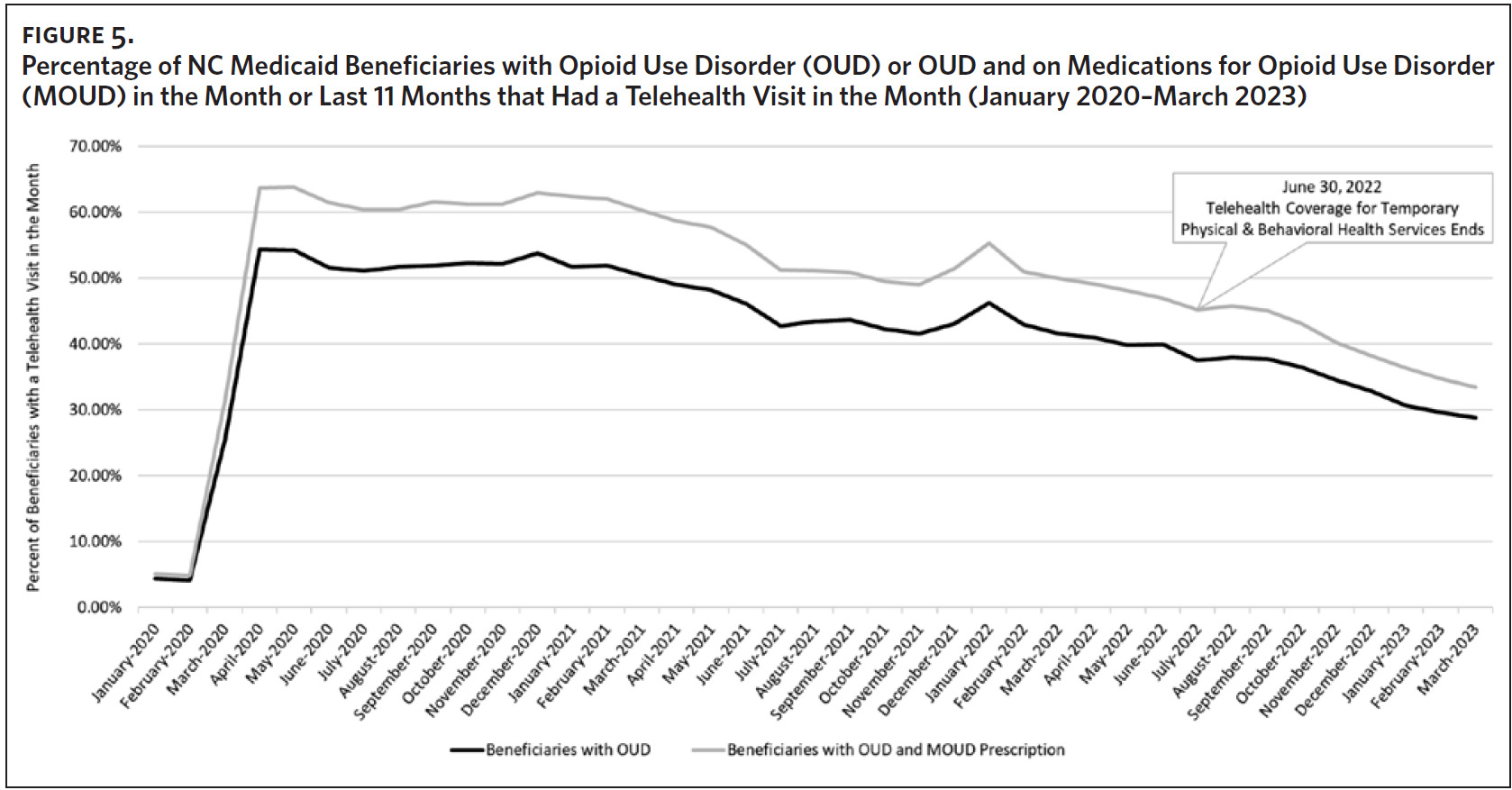

In addition to covering telehealth for physical health conditions, a majority of states added coverage for behavioral health services via telehealth to Medicaid policies, including expanding covered services and eligible provider types.16 Among the many telehealth-related NC Medicaid Provider Bulletins issued between March and June 2020, several addressed behavioral health services specifically.17 COVID-19 policies allowing telehealth for certain outpatient behavioral health services, such as diagnostic assessments and psychotherapy, have been made permanent.18 Other clinical coverage policies that have been made permanent allow for physician assessments or supervision of staff to be conducted virtually, potentially reducing the impact of provider shortages. Both behavioral health and physical health policies that were not made permanent lapsed on June 30, 2022. This coincides with a third, albeit smaller, drop in overall telehealth utilization.

Services relevant to the treatment of substance use disorder (SUD) for which telehealth flexibilities were made permanent include outpatient psychotherapy (can be provided by telehealth or telephonically); diagnostic assessment (can be provided by telehealth); peer support services (may be provided by telehealth or telephonically; audio-only communication limited to 20% or less of total service time per beneficiary per year). Policies discontinued as of June 30, 2022, include: substance abuse intensive outpatient program (service can no longer be provided outside of the facility by telehealth); substance abuse comprehensive outpatient treatment (service can no longer be provided outside of the facility by telehealth).

NC Medicaid beneficiaries’ use of telehealth has remained high in the behavioral health space, particularly for those with opioid use disorder (OUD) or those on medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (Figure 5). Telehealth visits for beneficiaries with OUD increased almost 500% at the onset of the pandemic. While utilization has slightly decreased over time, it remains high compared to the use of telehealth services among the entire NC Medicaid population.

NC Medicaid still saw substantial increases in overdose deaths, despite increased coverage of behavioral health services via telehealth modalities. The rate of overdose deaths increased by over 20% from the periods of November 2019– October 2020 to November 2020–October 2021, going from 34.9 deaths per 100,000 beneficiaries to 42.5 deaths per 100,000. While the timelines do not exactly align, trends among Medicaid beneficiaries and North Carolina residents overall are similar. Statewide overdose deaths increased 22% from 2020 to 2021, going from 31.5 to 38.5 deaths per 100,000 residents and from 3,304 to 4,041 total deaths.19

In the same 2020–2021 period, the opioid-involved overdose death rate increased by 34.5% among Medicaid beneficiaries, going from a rate of 1,535.5 deaths per 100,000 to 2,065.2 deaths per 100,000 and from 517 to 807 total deaths. Opioid-involved overdose deaths among all North Carolina residents increased 23% from 2020 to 2021, from 2,771 to 3,395 deaths.19 Nationwide, opioid-involved overdose deaths increased by 17% in the same period.20

Key Takeaways from NC Medicaid’s Payors, Care Management Organizations, and Providers

To better understand these trends, key informant interviews were conducted with payors, care management organizations, and providers. Interviewees’ perspectives varied, with one payor seeing consistent year-over-year growth in utilization and another payor noting that telehealth is not as widespread as it once was. A majority of informants described reliance on one or more technology platforms to assist in the delivery of telehealth, with some attributing their major successes to telehealth platform functionalities. This included synchronous audio-visual telehealth platforms, asynchronous e-messaging platforms, and self-directed wellness modules, the latter being an area of interest for payors to continue monitoring the health of their members between appointments.

Several common themes emerged regarding the gap that telehealth can fill. One example is telehealth increasing access to care for beneficiaries, in particular after hours, thereby reducing avoidable emergency department visits. One payor mentioned that they have “encouraged pediatricians in particular to have at least between the hours of five o’clock and nine o’clock staffed because that is the number one avoidable category…having that option, not just the telephone call… but an actual view connection with the doctor at the other end who’s empowered to treat the patient’s condition… that’s the promise that telemedicine offers.”

Transportation challenges were among the most cited barriers to care that telehealth can resolve. One provider mentioned that in addition to addressing unreliable public transportation, telehealth provides an opportunity for patients who may have physical limitations to be seen without the hassle of scheduling non-emergency transportation or the risk of being denied coverage for this type of transportation.

Informants also cited continued barriers to telehealth, specifically as it relates to broadband and access to the technology required for two-way audio and visual virtual visits. One provider noted that while a video visit is superior to a phone visit, it is important to recognize that “some people are really too poor to have cameras… [but] they should have access to care too.” This provider explained that “these were not families that had a lot of resources, so we would make do with a telephone… [but] even calling people on the telephone is complicated because a lot of people use phones where they buy a card with minutes on it. They run out of minutes, then you lose them… it’s hard.”

Despite these barriers, interviewees noted that both providers and patients have become more comfortable with telehealth: “We’re all more savvy than we were… none of us had ever heard of telehealth before 2020, and now people are pretty good at it.” Payors also noted that member experience and satisfaction with telehealth is high, with one payor reporting all their surveyed members rated satisfaction with telehealth services as either “excellent” or “good.” One provider stated that telehealth has actually deepened relationships: “When a dog barks or when they hear a kid [yell] ‘Mom,’ it’s very humanizing. And with my families… we’ve grown up together, we’re very close. I actually felt like there was kind of a side effect of [telehealth], even deepening that relationship and that rapport, knowing that they’re thought of as a human being too, who’s living all this craziness.” This same provider noted the importance of using telehealth services both responsively and proactively: “We did primary care pediatrics and had an extensive period when the clinic was completely closed, so people had no access to health care whatsoever, so telehealth was an incredible lifeline. We used it both responsively—so people would call in and we do visits that way—but we also used it proactively—so we pulled up a list, for example, of all our patients with asthma and reached out to each and every one of them to see how they were doing, to assess their asthma control, make sure they had the medications they needed, things like that.”

Interviewees reported mixed reception of telehealth in the behavioral health space. While some praise the flexibilities provided by telehealth, one provider noted that “a lot of teens, I will be completely honest, hate telehealth. The video is very exposing to them, and it’s just too much looking at their own faces.” Despite this hesitation by some members, interviewees highlighted that telehealth can be a good option for folks who cannot find a physician in their area or cannot find someone for their specific condition. One provider mentioned the ability of their members to access specialized care for eating disorders. Another payor specifically called out increased access to medication for opioid use disorder and behavioral health providers via telehealth.

In speaking with their members, one care management entity found that behavioral health services are easier to use because the stigma is lessened. Another organization mentioned that telehealth increases member choice and is one way to mitigate workforce shortages: “We have such a workforce shortage, and many people are able to work from home… having behavioral health kind of catch up with that I think has been helpful in the ability for our providers to serve our members.” Telehealth in the behavioral health space is not going away; as one health system reported two-thirds of their pediatric psychiatric encounters occurring virtually even today.

Interviewees expressed excitement when forecasting the future of telehealth. One organization highlighted that “telehealth has evolved in both use and acceptance,” while another commented that “this is the really exciting part, and this is where I hope we’re going to have increased adoption in North Carolina.” Many payors and providers alike stated that they have plans to expand or further modify telehealth services to meet the needs of members. Though, one entity noted that restrictions on service offerings and reimbursement can make it “hard for us to be creating, innovative, and dynamic in this space.”

Limitations/Future Analysis

Limitations to this analysis include only interviewing a small subset of payors and providers that contract with NC Medicaid. Interviewing a larger sample of key informants to gather a more comprehensive picture of telehealth utilization in North Carolina could glean different results. This analysis also prioritized the analysis of telehealth services among those with OUD and MOUD. Future analyses should look at the rates of opioid-involved overdose by beneficiaries who were receiving telehealth versus those who were not. It could be argued that the beneficiaries most likely to be vaccinated were the same beneficiaries who were most likely to be using telehealth to adhere to social-distancing guidelines during the public health emergency. A beneficiary-level analysis of telehealth utilization before and after COVID-19 vaccination may provide a better understanding of the driving factors in the correlation between the two.

Conclusion

NC Medicaid has hurtled through the telehealth space since March 2020. Changes in beneficiary access and utilization of telehealth services can be described by analyzing claims data, CAHPS survey responses, and discussions with key payor and provider informants.

Three distinct phases overlay shifts in beneficiary telehealth utilization: 1) North Carolina’s modified stay-at-home order and gradual re-opening in the spring of 2020, 2) COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the early part of 2021, and 3) sunsetting of temporary physical and behavioral health services in the summer of 2022. As beneficiary COVID-19 vaccination increased, use of telehealth services decreased. Concurrent offering of telehealth services decreased from 2021 to 2022, despite increases in beneficiary comfortability and sustained satisfaction with telehealth services. However, telehealth utilization remains high, particularly in the behavioral health space.

Key payor and provider informants across NC Medicaid highlighted the important role that telehealth can play in providing continued care for members and increasing access to certain provider types and specialties, particularly in cases where transportation is a barrier. Though some aspects of care look different in the behavioral health space, telehealth can provide access to specialized services and increase provider availability in the face of the behavioral health provider shortage. Overall, payors and providers expressed continued interest in expanding telehealth services for their members and patients, respectively. However, telehealth presents a new set of challenges, as there is evidence of overuse, misuse, and fraud, with some arguing that telehealth should be paid less than in-person visits.21–23 Given the complex environment, NC Medicaid will continue to monitor the use of these services, promoting appropriate telehealth use for patients and providers alike.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Marisa Domino and the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research for their support in developing this article.