“[Addiction] is not a moral failing, or evidence of a character flaw, but a chronic disease of the brain that deserves our compassion and care.”

— Vice Admiral Vivek H. Murthy, MD, MBA, US Surgeon General1“The road to recovery is not linear. It’s not straight. It’s a bumpy path, with lots of twists and turns. But you’re on the right track.”

— Candice Carty-Williams2

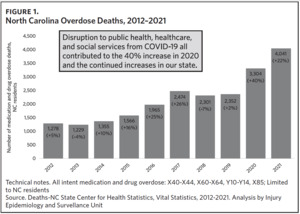

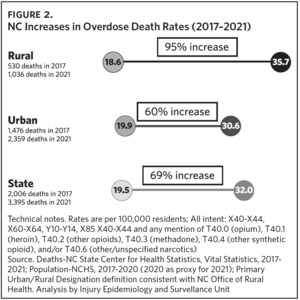

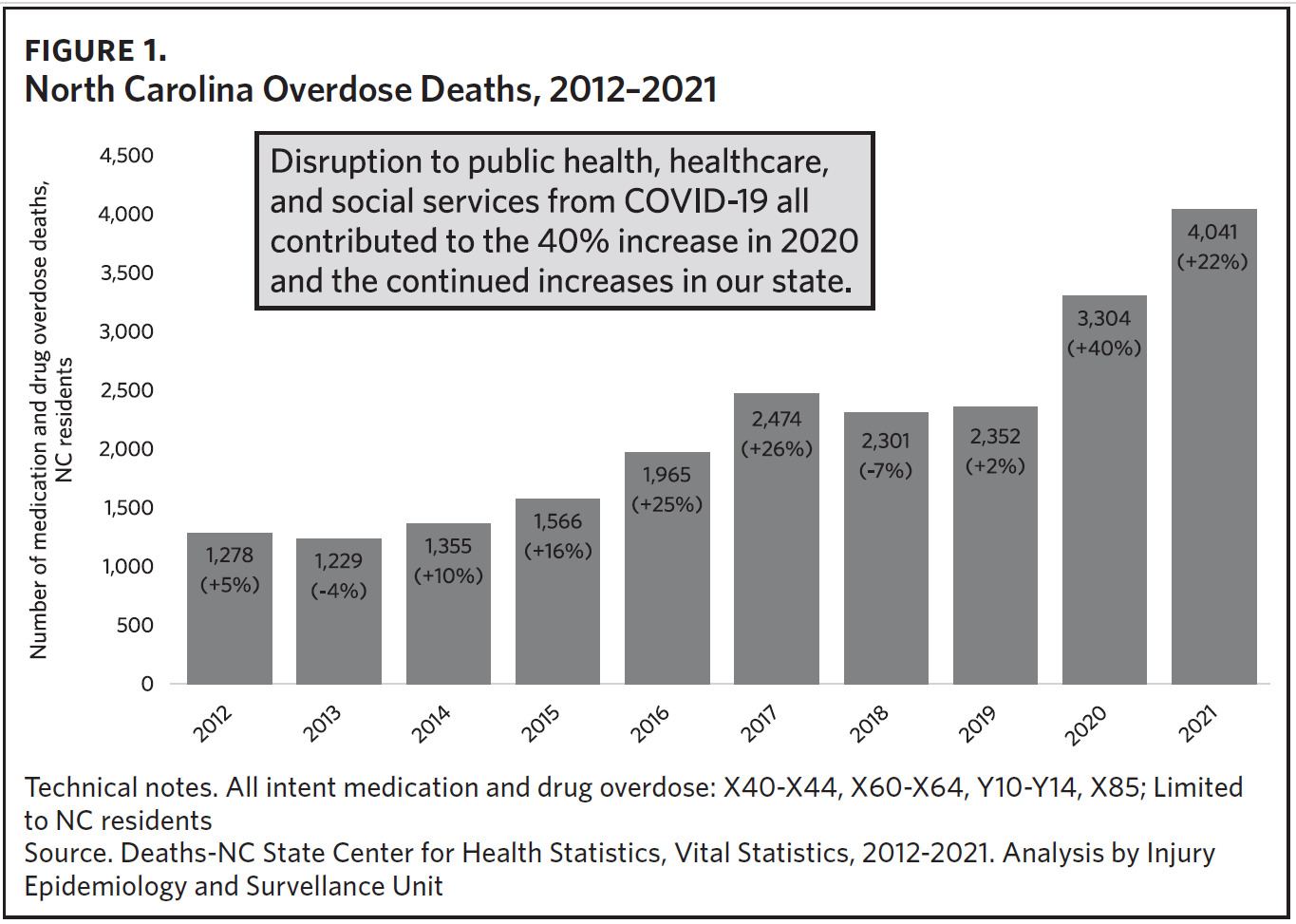

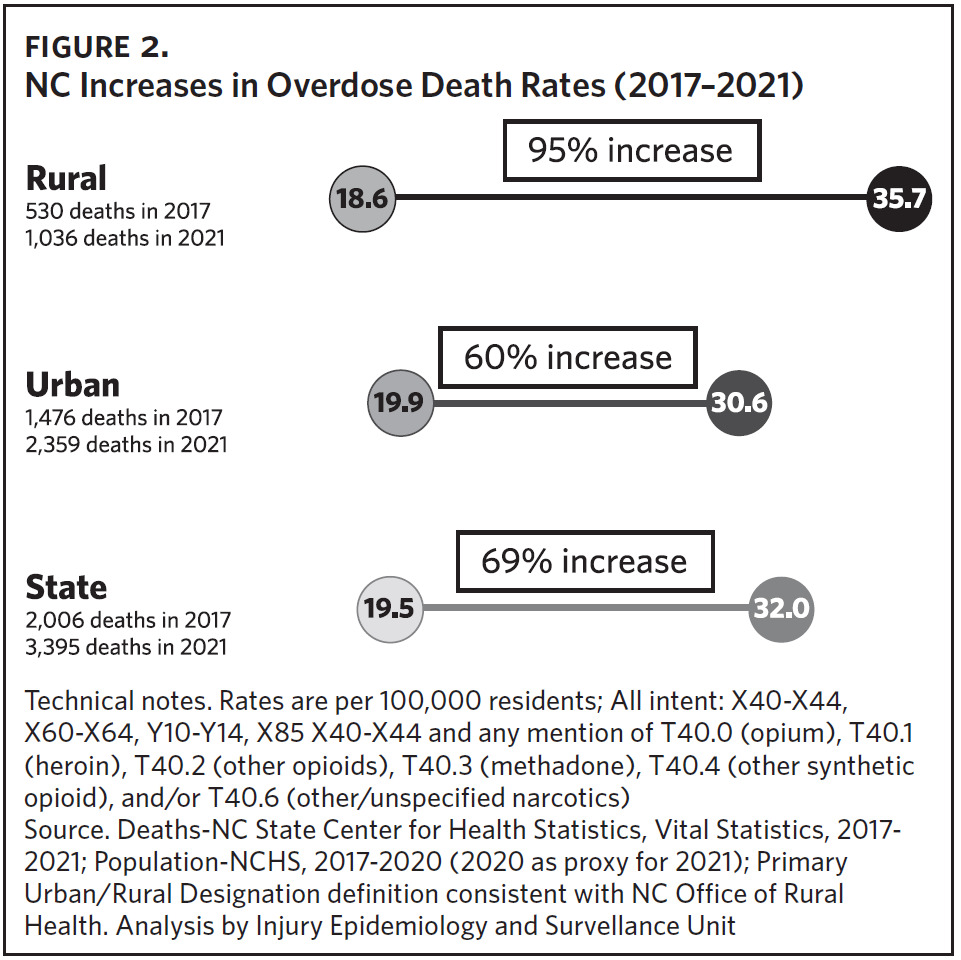

From 2020 to 2021, North Carolina experienced a 22% increase in overdose deaths. Disruption to public health, health care, and social services from COVID-19 all contributed to the 40% increase in 2020 and the continued increases in our state through 2021 and 2022.3 Emergency department (ED) visits for overdoses involving medications or drugs with dependency potential (such as opioids) increased 12% in 2021.4 Rural counties saw the largest increase in opioid-involved overdose death rates from 2017 through 2021. In 2017, North Carolina saw 530 deaths in rural counties due to opioid overdose, and in 2021 that number rose to 1,036 deaths; from 2017 through 2021, rates of overdose increased 69% across the state from 19.5 per 100,000 residents in 2017 to 232 per 100,000 residents in 2021.4 Illicit opioids, predominantly fentanyl, were involved in approximately 93% of all opioid overdose deaths in 2021.4

Unfortunately, most people with opioid use disorders are not getting effective, evidence-based treatment. According to the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), an estimated 2.5 million people aged 18 and older had opioid use disorder in the past year, yet only 36% of them received any substance use treatment, and only 22% received medications for opioid use disorder.5 Why is this?

Many people and communities lack access to basic treatment and lack understanding of how to even find treatment. Many avoid treatment due to the intense stigma attached to substance misuse, help-seeking, and use of medications like methadone. But one of the biggest issues we have dealt with here in North Carolina is lack of insurance coverage for adults, especially men with substance use disorders. In the NSDUH survey, individuals reported not seeking treatment for reasons including lack of health coverage and inability to afford the cost of treatment (24.9%), not knowing where to find treatment (15.8%), and concern that getting treatment might have a negative effect on their job (14.7%).5

Recently I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of passionate county advocates about opioid misuse and state strategies to address prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and overdoses in our communities. At the end of the talk, a gentleman came to speak to me. In hushed tones, he asked my opinion of long-term methadone use. His daughter had been on methadone for many years, was well into recovery, and had rebuilt her life in amazing ways. Despite all of this, his concern was his daughter’s prolonged use of methadone. Despite the evidence that his daughter was well—in fact, thriving—he had grave concerns that she remained “addicted” to opioids. After such a brief conversation, I don’t pretend to understand the dynamics of their relationship or any potential unaddressed trauma they were dealing with. I do, however, know something about the dynamics of the profound stigma we have associated with life-saving, evidence-based, effective opioid use treatment, especially medications.

Opioid use disorder is a chronic disease. Like other diseases, it has a progression of symptoms and a set of treatment protocols. Opioids affect brain chemistry in both short-term and long-lasting ways. In the short term, opioids cause feelings of euphoria and can reduce symptoms of pain. Over time, the brain becomes acclimated and needs more of an opioid to produce the same effect or to ease the withdrawal symptoms a person feels when they are not taking the opioid.6 Some people are more susceptible to the effects of opioids, and for some people intense cravings, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, and dependency can happen in only a matter of weeks.6 Opioid use disorders can lead to or exacerbate life stressors and usually, as the disease progresses, it takes a heavy toll on relationships, employment, and income. One sign of the disease is that the person continues to use even as it affects other parts of their lives or has serious physical health issues or legal implications. This is because as use progresses, the brain is changed in fundamental ways that reinforce continued use.6

These brain changes from chronic opioid use can persist for years even after a person stops using, making the potential for relapse high and underscoring the need for long-term treatment approaches. Effective treatment is typically a combination of medication for opioid use disorders (MOUD) and forms of therapy including individual, group, and family therapy. Often a person may need help rebuilding what they have lost (i.e., employment, housing) or even managing the legal ramifications of use. It is important to understand that opioid use disorders are chronic, like diabetes or hypertension, and treatments including MOUD are often needed long term in order to help an individual maintain their recovery. Common MOUDs include methadone, buprenorphine, Suboxone, Sublocade, and Naltrexone. These medications help to reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms and restore balance to the brain circuits affected by chronic opioid use.6

To put it all together, opioid misuse is a chronic disease that affects the brain. Treatment, including MOUD, is needed long term to help a person maintain their recovery. Many people in recovery count their success day by day. It is not uncommon to meet a person in recovery who will let you know that they are 100 days without using; 1,000 days without using; 3,000 days without using. Imagine maintaining the ups and downs of treatment, which may include a maintenance medication like buprenorphine or methadone, meeting with your psychiatrist, going to group therapy, being hospitalized for detox or overdose. All of those things can happen in the course of a month or a year, or the many years that the recovery process could take. Imagine doing this without insurance. Imagine that you are a person ready for treatment (which can be the hardest step) and you find a provider that you trust (which is also really hard), and you find transportation to that provider, and the provider tells you that the cost of one day of outpatient treatment inclusive of medications is $200. And you’re advised that you should come every day, for as long as it takes, to achieve and maintain your recovery.

Based on July 2023 population estimates and NSDUH prevalence estimates, there were an estimated 225,815 uninsured adults (aged 18–64) in North Carolina with a substance use disorder (SUD). States, including North Carolina, have limited funds for treatment outside of insurance, and often those funds—whether allocated by the General Assembly or by federal grants—need to be used for prevention, harm reduction, and treatment coverage for the people who are uninsured. From July 2021 to June 2022, 43,782 of these uninsured individuals (19.4% of the estimated uninsured with a SUD condition) received some form of SUD treatment using state-funded services. Said another way: from July 2021 to June 2022, only 19.4% of uninsured adults with a SUD condition in North Carolina received a state-funded treatment service for that condition. And for those who were able to receive such services, it is unlikely that those dollars are enough to cover the lengthy but necessary treatment needed to maintain recovery over multiple years.

North Carolina has more than 80 outpatient opioid treatment programs across the state that provide services, including MOUD, to more than 30,000 individuals. Conservative projections point to 30%–60% of those individuals now being eligible for Medicaid coverage. Studies show that among adults with opioid use disorders, those with Medicaid were significantly more likely to receive treatment than those with private coverage. According to the 2017 NSDUH, just over a third (34%) of adults with OUD received any drug and/or alcohol treatment in 2017. However, those with Medicaid were nearly twice as likely as those with private insurance to have received drug and/or alcohol treatment (44% versus 24%).7

NC Medicaid’s substance use treatment benefit is robust. Over the past several years, North Carolina has been one of few states that cover the full American Society of Addiction Medicine continuum of care for substance misuse disorders. This is a very good thing. It means that regardless of stage of recovery, people can receive the proper level of medically necessary substance use treatment including detoxification, hospitalization, intensive outpatient programs, counseling, and MOUD. Access to these benefits will change the lives of thousands of people in North Carolina.

Acknowledgments

No conflicts of interest were reported.