NC Medicaid is amid a transformation to value-based care models, which requires the consideration of models to best serve the 1 in 5 NC Medicaid beneficiaries dually enrolled in Medicare.1 Disjointed Medicare and Medicaid administration, financing, and care may contribute to suboptimal health outcomes and care experiences for beneficiaries.2 Integrating Medicare and Medicaid to improve care for dually enrolled individuals requires knowledge of the demographic, eligibility, and enrollment trends of these individuals throughout North Carolina.

In general, dually enrolled individuals use more services than individuals solely insured by Medicare or Medicaid, and per-person costs for dually enrolled individuals are substantially higher (some estimates as high as 1.5 times) than for the average Medicare beneficiary.2–5 Individuals typically qualify for Medicare due to age or disability, and the level and extent of Medicaid support varies based on income and asset limits and unmet health care needs. Inefficient communication and fragmented care are among many reasons for higher care delivery costs for dually enrolled individuals. Issues with communication and fragmented care may lead to suboptimal health outcomes, such as potentially avoidable emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations.2,6–8 Additionally, beneficiaries’ care needs, such as culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) or long-term support services,9,10 may vary widely within a single state. These issues are particularly impactful for the dually enrolled population, members of which tend to experience more functional limitations with activities of daily living and chronic conditions and receive less social support than Medicare-only beneficiaries.2

Within the past decade, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and individual states have made significant efforts to facilitate integration by aligning Medicare and Medicaid administrative processes, care delivery, and financing. Despite mixed results across states,11,12 national enrollment in integrated models increased from 160,000 in 2011 to 1 million in 2019.2 State initiatives continue to play a major role in improving alignment between the two programs and improving care experiences for dually eligible beneficiaries.13,14 Current efforts to integrate Medicare and Medicaid include the Financial Alignment Initiative (FAI) demonstration model, a capitated model called Program of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), and Medicare Advantage plans that serve dually eligible individuals, known as Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs).7 Among current integration efforts, PACE is the only program in North Carolina that integrates Medicare and Medicaid administration, financing, and care; however, PACE has restricted eligibility to beneficiaries aged 55 years and older who meet institutional level of care criteria, are willing and able to live in the community, and receive long-term support services (LTSS). D-SNPs are designed to support Medicare-Medicaid integration and require a contract with the state Medicaid program; however, the D-SNPs serving North Carolina currently do not meet the CMS criteria for highly or fully integrated. These distinctions suggest that while North Carolina may learn from other states’ experiences, each state needs to understand certain characteristics of its dually eligible populations (e.g., the presence of disability, socioeconomic status, and need for certain types of long-term services and supports or behavioral health services) when designing integrated care programs.

North Carolina’s large-scale transformation in the delivery of Medicaid from fee-for-service (FFS) to Medicaid managed care (MMC) began in 2021. Some Medicaid beneficiaries, including those dually enrolled in Medicare, were exempted from the initial conversion to MMC. Rather, at the direction of the North Carolina General Assembly (S.L. 2015–245), the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) published a report in 2017 outlining its strategy for providing medical, behavioral, and LTSS care to beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid through managed care using capitated contracts.1 Our study seeks to provide context and evidence base for the state to address the considerations raised in this report.

Designing a Medicare-Medicaid integration strategy for North Carolina requires understanding the dually eligible beneficiaries in North Carolina: who they are, what care they need, and what benefit delivery systems are currently available to them. This study advances knowledge by describing the North Carolina dually eligible population and enrollment in Medicaid programs using recent NC Medicaid administrative data. We also describe Medicare managed care plan enrollment trends across the state using public data. The findings in this study will inform North Carolina policymakers as they consider options for integrating the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Methods

Our study used restricted Medicaid enrollment data and Medicare state buy-in indicators to describe characteristics, eligibility, and the full-benefit dual-eligible (FBDE) population in North Carolina. Dual-eligible benefits may include Medicare cost-sharing known as “partial benefits,” alone or in addition to full Medicaid coverage, known as “full benefits.”

We focused on individuals eligible for full Medicaid and Medicare benefits because individuals eligible for partial Medicaid benefits (who are ineligible for full Medicaid services) have less to gain from integration.

Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment

Our FBDE cohort included individuals with full Medicaid benefits concurrently enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare, as determined by Medicaid data and confirmed by Medicare data. Included beneficiaries were dually eligible for at least 16 days of one month. Beneficiaries’ dual eligibility categories could change over time and thus were not mutually exclusive for reporting any enrollment.

Outcomes included Medicaid eligibility, eligibility changes, and benefit delivery system enrollment. We defined full-benefit eligibility categories as Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries with full-benefit Medicaid (QMB+), Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries with full Medicaid coverage (SLMB+), Medically Needy, and Categorically Needy in accordance with NC Medicaid data. Among FBDE individuals, SLMB+ and QMB+ individuals receive assistance from Medicaid with paying their Medicare premiums.15

Other FBDE individuals may classify as Categorically Needy (in general, receiving Supplemental Security Income) or Medically Needy, or qualify for other state-specific programs including Medicaid Aid to Families.16 We defined benefit delivery system enrollment using NC Medicaid program data. We did not require continuous eligibility for full benefits, so FBDE beneficiaries who had only partial Medicaid benefits at some point during the year were categorized as QMB, SLMB, or Qualifying Individual (QI). Benefit delivery systems providing full benefits included PACE, waivers, and FFS. Waivers included the 1915(c) Medicaid Home and Community-Based (HCBS) Waivers, known as Community Alternatives Programs, for youth under age 20 (CAP/C) and adults over 18 with disabilities (CAP/DA) to receive care advisors and LTSS. In North Carolina, 1915(b) waiver programs provide additional services for individuals with behavioral health or intellectual/developmental disabilities (BH/IDD) and traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Categories are not mutually exclusive.

To inform future state decision-making, we also identified individuals fitting NCDHHS-defined eligibility requirements for the future tailored prepaid health plans (TPs).

While implementation has been delayed as of March 2023, TPs are intended to deliver additional behavioral health services for individuals with BH/IDD or TBI. We stratified outcomes by age as of January 1, 2019, and identified demographic characteristics including beneficiary-reported sex, race, and ethnicity from Medicaid enrollment data. We also categorized beneficiaries’ county of residence as rural, urban, or unknown based on NCDHHS designation.17

Medicare Managed Care Plans

We measured Medicare managed care plan enrollment and availability by pairing Medicare Advantage/Part D Contract and Enrollment Data with the “Monthly Enrollment by Contract/Plan/State/County (CPSC)” file, both from CMS, for July of each year examined.18 We obtained state and county-level enrollment data for Medicare-Medicaid dually eligible beneficiaries with full Medicaid benefits from the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office’s “Quarterly Release of the National, State, and County Enrollment Snapshot” file.19 We used quarter two (Q2) enrollment data. The most recent Q2 data available was for June 2020.

For regional plans covering multiple states, we estimated North Carolina enrollment as total plan enrollment weighted by the fraction of North Carolina dually eligible individuals relative to all states serviced in the plan. We also categorized benefits in the D-SNP plans listed in the Medicare Advantage/Part D Contract and Enrollment Data from each existing managed care plan servicing North Carolina.20–35 Measures included existing managed care program penetration rates, or the percent of all FBDE beneficiaries enrolled in PACE or D-SNPs, and the geographic availability of and benefits offered by these managed care plans. We also compared D-SNP participation to other states chosen by geographic proximity.

Results

Overall Enrollment by Program Eligibility Category

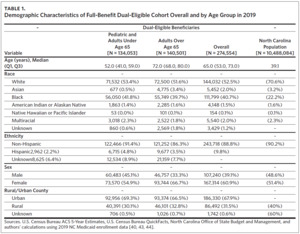

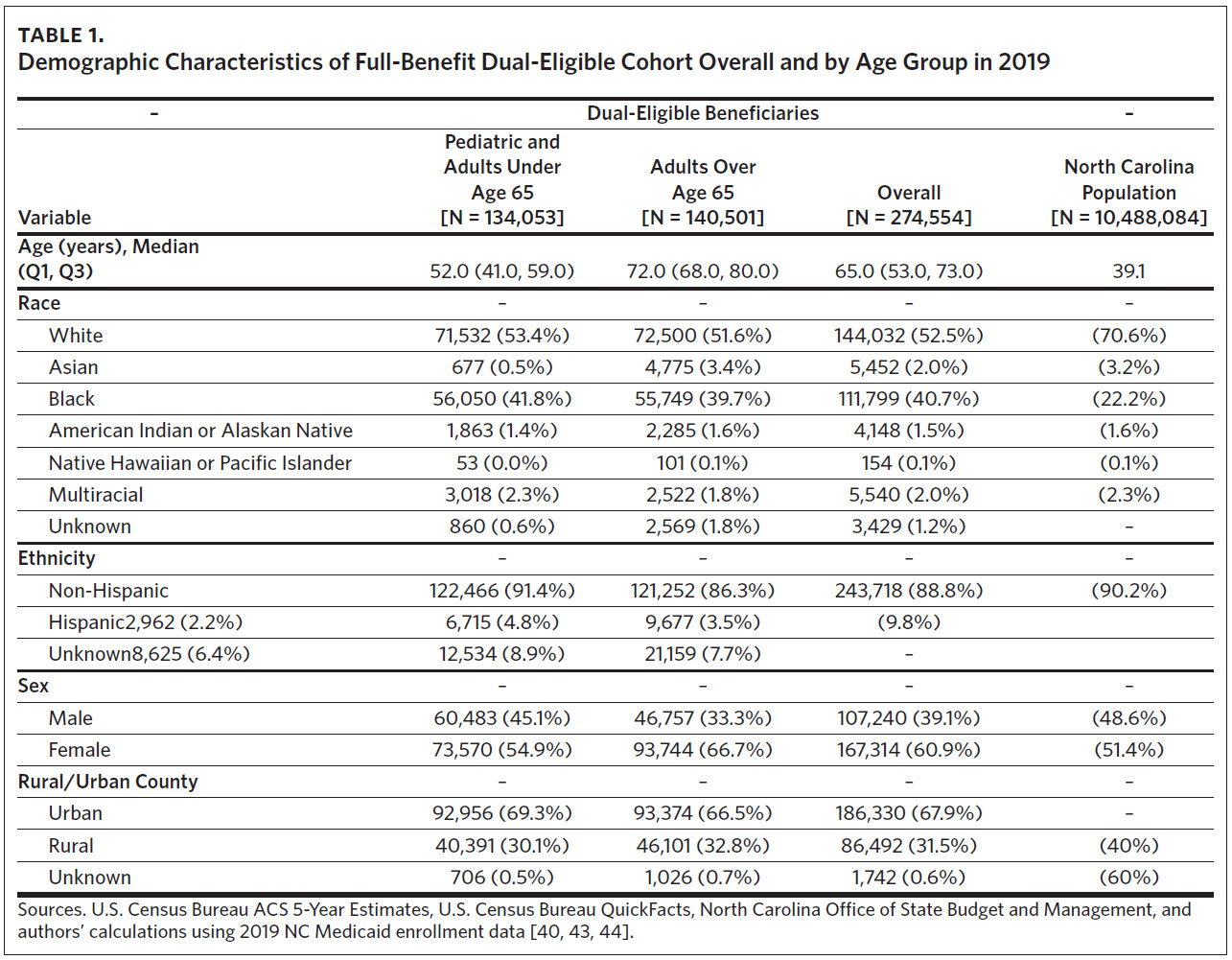

Of 274,554 beneficiaries in the 2019 FBDE cohort, nearly half (48.7%) were under age 65, with a median age of 52 (Table 1). Common race and ethnicities included White (52.5%), Black (40.7%), Multiracial (2.3%), American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) (1.5%), and Asian (0.5%); 3.5% were of Hispanic ethnicity. Nearly 70% of dually enrolled beneficiaries reside in urban counties.

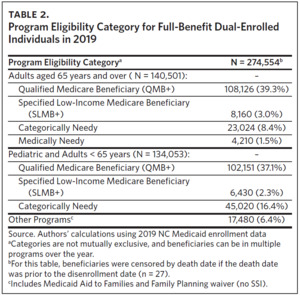

Most (76.4% [39.3% + 37.1%]) met QMB+ eligibility, and among QMB+, about half (51.4%) were eligible for Medicare due to age (Table 2). Few (2.3% and 3.0%) met CMS SLMB+ eligibility criteria among both eligible groups. Approximately one-quarter met Medicaid eligibility criteria for Categorically Needy, and among Categorically Needy, two-thirds qualified for Medicare due to a disability. Few (1.5%) met Medicaid eligibility criteria for medically needy and were age-eligible for Medicare. Another 6.4% of individuals were eligible for Medicaid benefits through other North Carolina-specific eligibility criteria like Medicaid Aid to Families.

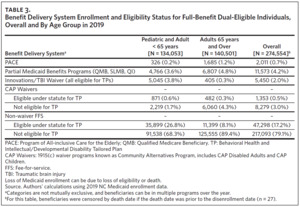

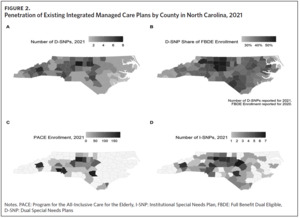

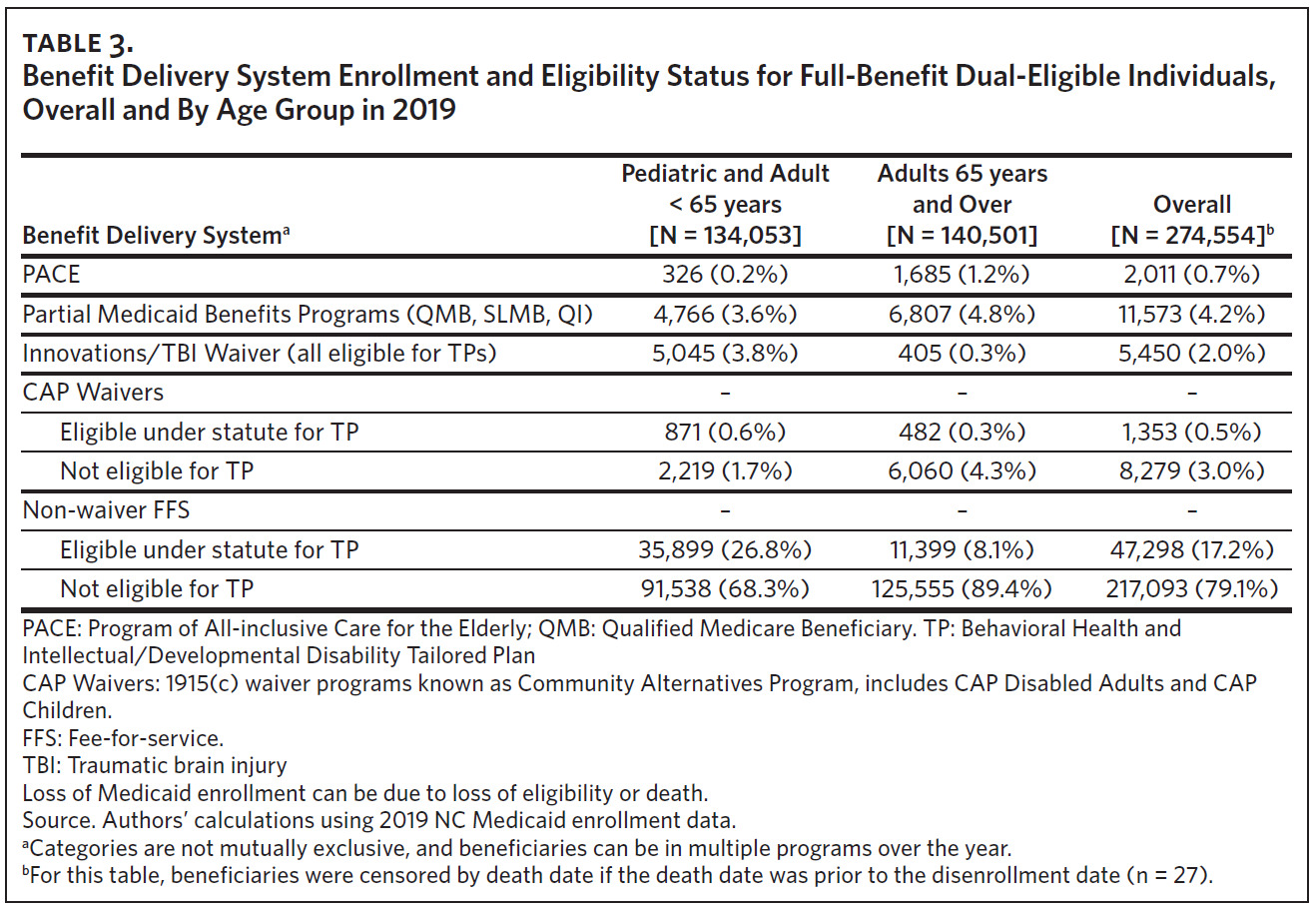

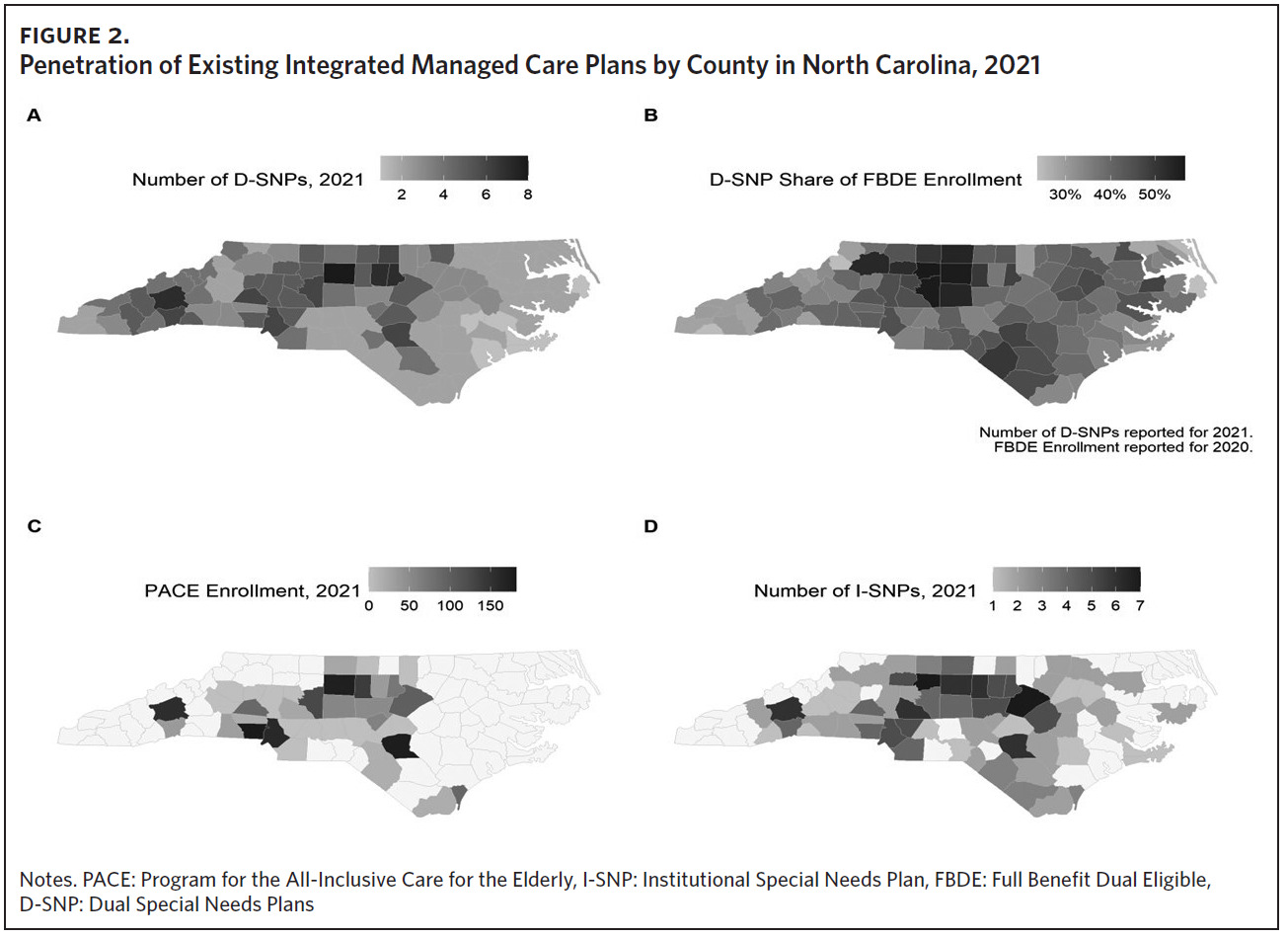

A majority of our cohort (96.3% [17.2% + 79.1%]) received Medicaid benefits through FFS (Table 3). Less than 1% of the cohort were enrolled in PACE in 2019 (Table 3). Most PACE enrollees were over age 65, but 326 of 2,011 total PACE enrollees (16.2%) were aged 55 to 65. North Carolina currently has 11 PACE programs (17 plans, some with separate offerings for dually eligible versus Medicare-only individuals) in 36 counties (Panel C of Figure 2). About 20% of the FBDE population, including Innovations and TBI waiver participants, would potentially be eligible for TPs, with a greater proportion under age 65.36

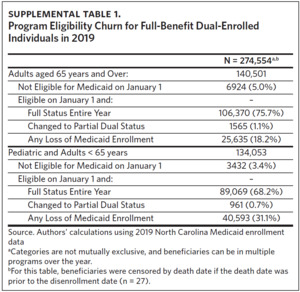

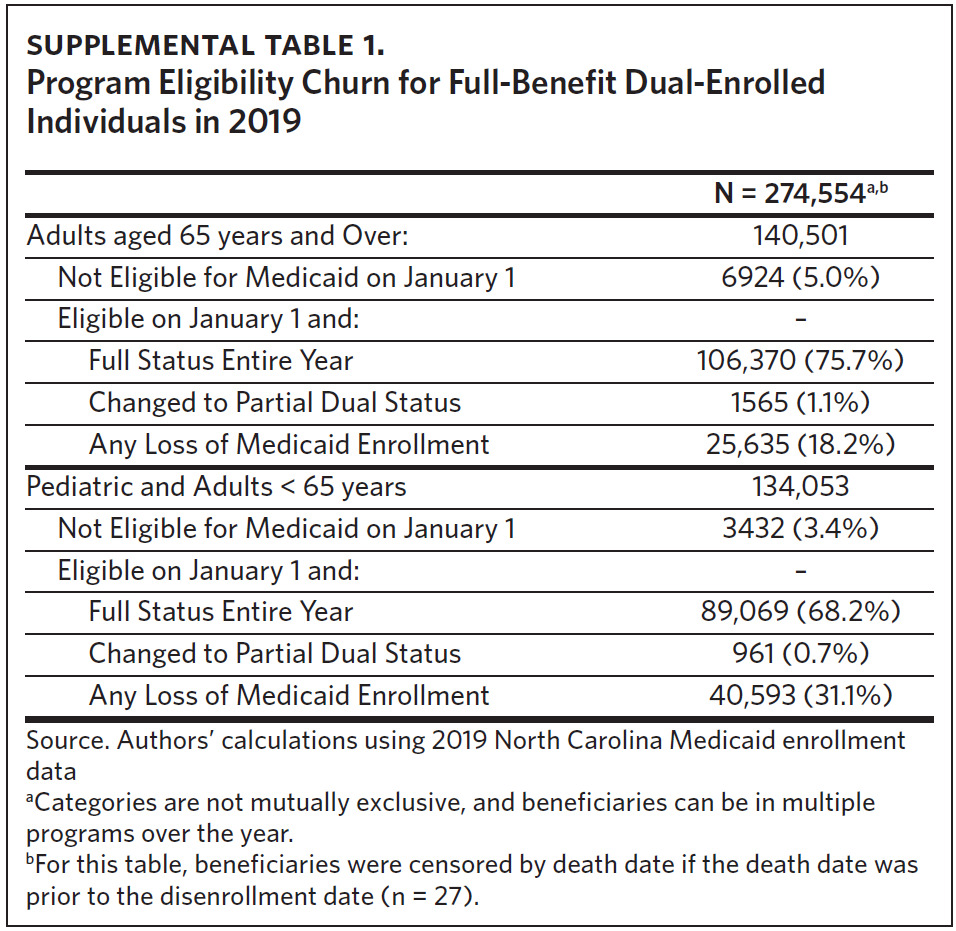

Three-quarters of the cohort (n = 195,439, 74%) were eligible for full Medicaid benefits for the entire year (Supplemental Table 1). Of those who lost full Medicaid benefits at some point during the year, over 60% were under age 65. Only 4% of beneficiaries (n = 10,371) were not full-benefit dual-eligible on January 1 but became eligible at some point during the year; individuals aged 65 and over account for the majority (67%) of this group. A small percentage (1%) of FBDE beneficiaries changed from full Medicaid benefits to partial Medicaid benefits in 2019.

D-SNP Availability and Participation

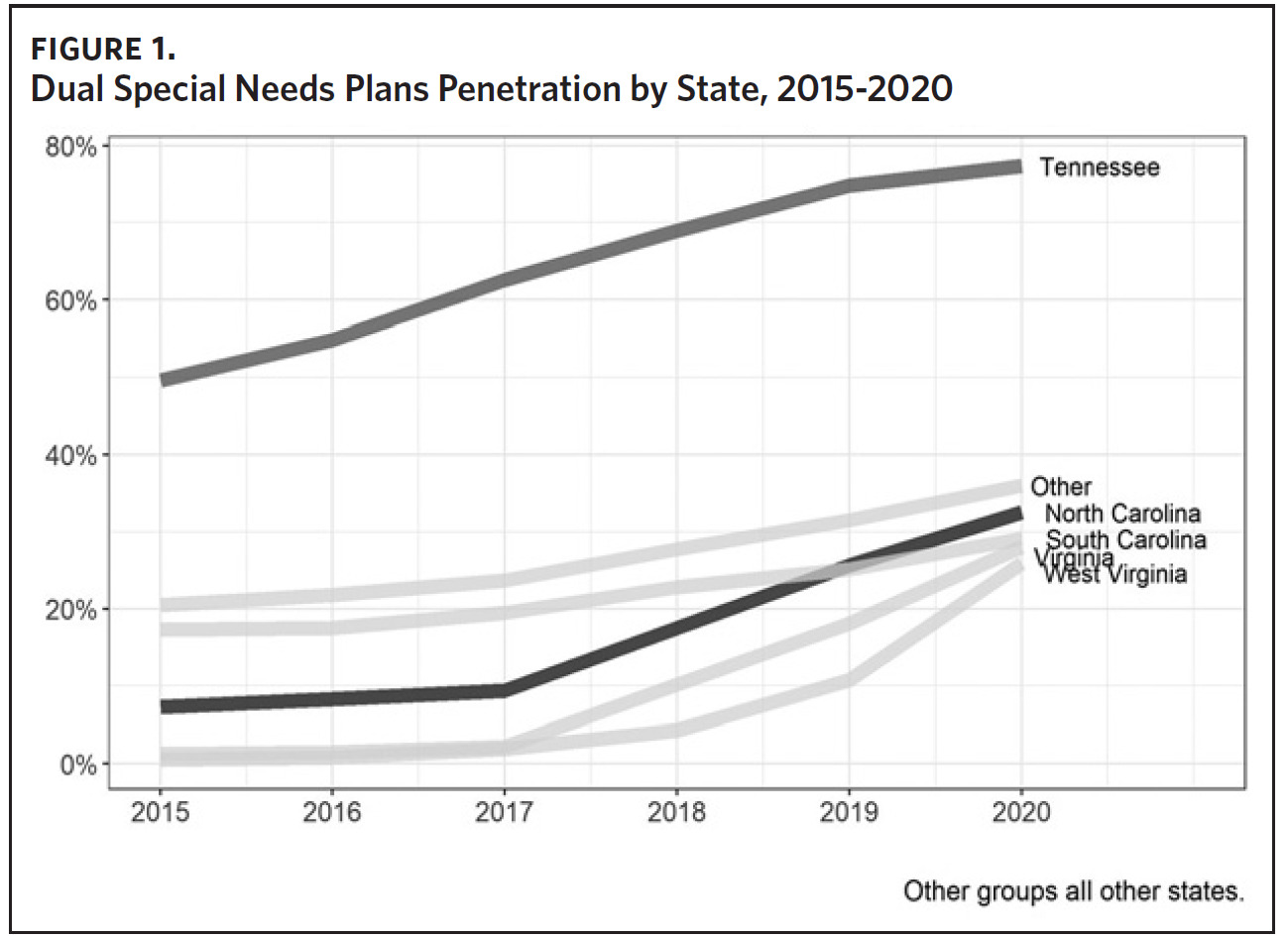

Enrollment in D-SNPs increased substantially in North Carolina from 17,479 (7.3% of FBDE individuals) in 2015 to 107,283 (32.5%) in 2021, reflecting a 25% year-over-year growth in 2020 and 2021. D-SNP penetration was in line with that of most neighboring states; the exception is Tennessee, which is highest among all 50 states (Figure 1).

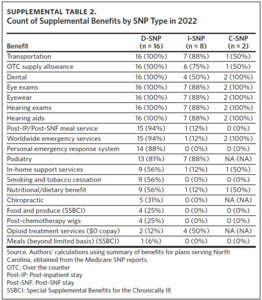

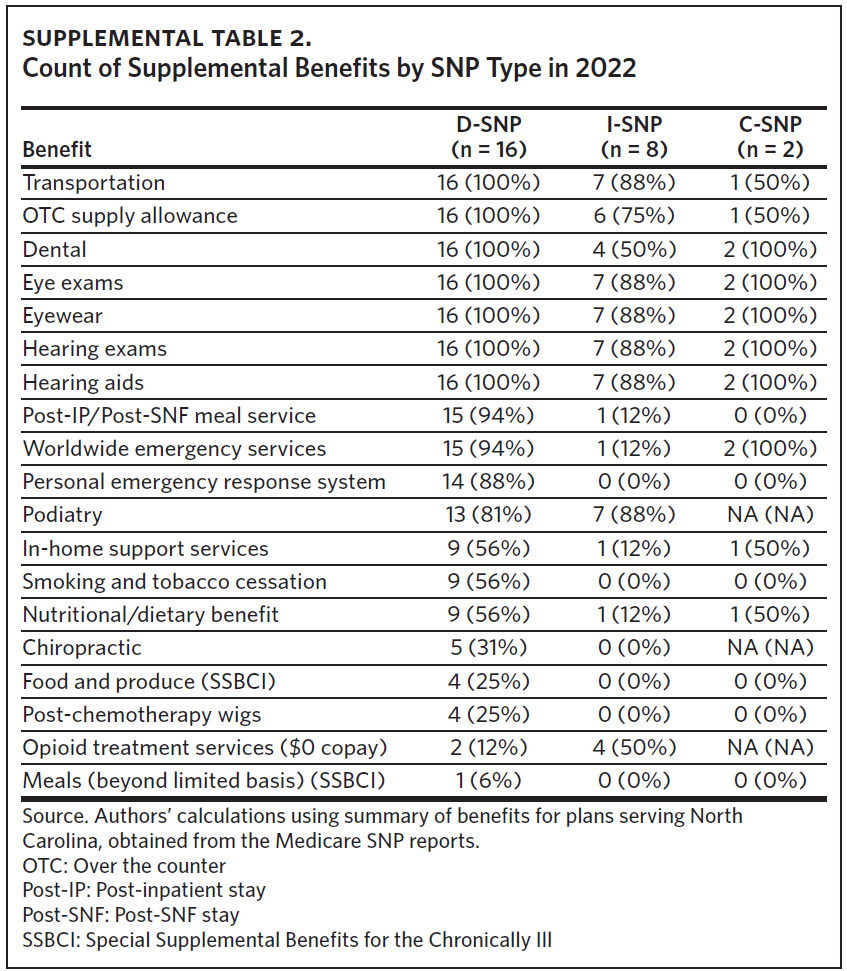

In 2021 there were 16 D-SNP plans available in North Carolina with at least one D-SNP available in all North Carolina counties. D-SNP penetration was higher in urban centers and adjacent counties, including the Triad region (Guilford and surrounding counties) and southeastern North Carolina (Cumberland and Robeson counties) (Panel B of Figure 2). Both regions had a higher portion of Black, Hispanic, and Native American residents, older populations, and elevated poverty rates compared with the state average.40,41 In addition to providing dental, vision, hearing, transportation benefits, and prescription drug benefits, most D-SNPs offered in-home support services, short-term post-skilled nursing facility or inpatient stay meal services, and smoking cessation programs as additional benefits (Supplemental Table 2).

Dually eligible enrollees who are residents of long-term care institutions may have the option to enroll in an Institutional Special Needs Plan (I-SNP). North Carolina had seven I-SNPs in 2021, with the largest concentration in the Triad and Triangle regions (Panel D of Figure 2).

Discussion

This study provides a timely, detailed description of beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid that may be valuable for North Carolina policymakers as the state seeks to integrate Medicare and Medicaid programs.

In 2019, we found that individuals eligible for full Medicaid and Medicare benefits were largely served by FFS Medicaid benefits, and Medicare benefits are increasingly provided under managed care plans like D-SNPs. Very few dual-eligible individuals were enrolled in PACE, the only fully integrated benefit delivery program in the state. This landscape analysis suggests there is a need to expand options that integrate Medicare and Medicaid services to improve care for dual-eligible beneficiaries in North Carolina. Leveraging the current PACE and D-SNP infrastructure may minimize disruption for dual-eligible individuals and their care partners. Additional research is underway to improve understanding of the diverse care experiences among dual-eligible beneficiaries and inform strategies for Medicare and Medicaid integration in North Carolina. The 2017 North Carolina Managed Care Strategy for Dual Eligibles stressed that North Carolina approaches for Medicare-Medicaid integration should minimize suboptimal access to care, poor health outcomes, disjointed experiences with the care delivery system, and high costs for beneficiaries. Medicare-Medicaid integration should ensure health equity in respect to the diversity of beneficiaries’ racial, disability, eligibility, and health care statuses. An integrated strategy may help minimize unnecessary disruptions in care due to loss of Medicaid benefits, particularly among adults under age 65 with disabilities, and leverage the existing D-SNP and PACE penetration to minimize disruption for FBDE individuals.

Based on this landscape analysis of dually eligible beneficiaries’ Medicaid enrollment, demographics, benefit plans, and existing D-SNP penetration, North Carolina should make the following considerations as they seek to integrate care for FBDE individuals:

Importance of Health Equity in Health Care Access and Delivery Decisions for the Dual-Eligible Population

Careful consideration should be given to these differences to help ensure person-centered, holistic care. As North Carolina considers various integration mechanisms, the choices could have important consequences for the FBDE population, which is diverse and has complex needs.42 We found an overrepresentation of Black people (41.8%) among dually enrolled beneficiaries compared with the Black population in North Carolina (22.2%),37 and about half of North Carolina’s FBDE beneficiaries were below age 65 and qualified for Medicare through disability.

The wide range of ages and disabilities of these beneficiaries require special consideration from policymakers, particularly as the state considers how best to support not only the beneficiaries, but the beneficiaries’ caregivers and families. North Carolina’s rurality poses specific challenges for equity. NCDHHS recommended phasing in capitated contracts in rural areas in its 2017 report because of the need to develop more robust provider networks in rural counties.

The high concentration of D-SNP plans in relatively populous regions of the state may support this need to develop more robust options in rural areas. However, delaying rural integration could disproportionately harm rural populations and further entrench existing inequities between rural and urban communities.43

The FBDE population also includes several groups with high acuity and complex needs. For example, we found that nearly 20% of the 2019 dual-eligible population would qualify for the TPs as specified in current guidelines. These beneficiaries will require additional behavioral health support.

Integration mechanisms could be used to enhance coordination of care for these patients, as well as patients who use services that were traditionally offered by local management entities/managed care organizations (LME/MCOs).

Disruptions in Care Due to High Rates of MedicaidBenefits Loss

Churn occurs when beneficiaries lose access to Medicare or Medicaid due to eligibility changes, incomplete re-enrollment processes, or voluntary changes in enrollment. Gaps in enrollment due to churn impact beneficiaries’ access to care and create administrative burden for the Medicaid program and providers seeking to coordinate care and improve outcomes. Our analysis found that FBDE beneficiaries under age 65 cycle in and out of full-benefit dual eligibility at over twice the rate as their counterparts over age 65. Considering the rates of churn among both groups, the state will need to consider who is eligible for any integrated products and the necessary processes to ensure continuity of care. Further, developing an implementation strategy that will minimize disruption of services for FBDE individuals, who are already likely to experience disruption, could ease the transition and improve buy-in from beneficiaries.

It is critical to understand churn rates among subgroups of the dually eligible population, such as members of marginalized communities, those eligible for behavioral health TPs, or beneficiaries utilizing LTSS. High-acuity behavioral health services are carved out of Medicaid standard prepaid health plans (PHPs) and will be provided by TPs (previously LME/MCOs) when they launch. Disruption in these intensive services may have substantial negative effects on beneficiaries. Developing strategies to minimize disruption of services may improve health outcomes of high-risk beneficiaries.

Opportunities to Leverage Current Plan Infrastructure and Enrollment

Leveraging the existing D-SNP and PACE penetration would be least disruptive for dually enrolled individuals as the state transitions to integrated managed care products, particularly among individuals currently enrolled in the programs.

Approximately three-quarters of D-SNP beneficiaries are currently enrolled in a plan managed by an entity that also manages a Medicaid standard plan. Of the five entities offering a Medicaid PHP in North Carolina, four entities offer the Medicare D-SNP plan in at least some North Carolina counties.44,45 The surge in D-SNP enrollment coincided with an expansion in the number of plans available to North Carolinians (six in 2017, nine in 2018, and 16 in 2021), and an increased focus by NCDHHS on enrolling dually eligible individuals in D-SNPs in 2017.46 However, D-SNP penetration varies by geography and strict eligibility requirements contribute to low (~1%) enrollment in PACE programs among FBDE individuals. Only one insurer has a statewide plan option for both Medicare and Medicaid, so expanding the service areas for other D-SNP plans could improve opportunities for alignment with Medicaid plans.

As the state considers integration options, assurance of high-quality option availability throughout the state will be important, as will careful messaging to beneficiaries, the majority of whom have elected not to enroll in a D-SNP. Policymakers may be able to take valuable lessons from other states’ integration efforts. For example, Pennsylvania and Tennessee engage in default enrollment of newly eligible Medicare beneficiaries served by a Medicaid managed care plan into an aligned D-SNP.46 While each state is unique in its demographics and political context, NC Medicaid shares some similarities with Pennsylvania and Tennessee.

Specifically, they each have large rural areas and diverse Medicaid populations; however, Pennsylvania and Tennessee have a longer history of using Medicaid managed care than North Carolina. Learning from other states’ experiences may facilitate successful integration in North Carolina.

Limitations

There are important limitations associated with this study. We restricted our analyses to describing enrollment and benefits plan participation for dually eligible beneficiaries in 2019 to ensure our results did not conflict with Medicaid actions during the COVID-19 public health emergency in 2020. We also opted to exclude health outcomes and utilization, as these were outside the scope of this project.

Finally, we measured churn as any loss of dual eligible status during the period; however, Medicaid beneficiaries may cycle in and out of Medicaid eligibility and different benefit delivery programs. As a result, we may have underestimated the potential disruption caused by churn and changing benefits over time.

Conclusion

Lack of integration between Medicare and Medicaid plans creates challenges and inefficiencies in finance, care, and administration that can adversely impact beneficiaries’ outcomes and experiences of care. Our findings offer guidance to North Carolina and other states considering strategies for Medicare and Medicaid integration to better serve a diverse, complex dual-eligible population. As North Carolina continues to develop its integration strategy, continued research and stakeholder engagement will be needed to inform and tailor the approach to improving health equity and health outcomes for beneficiaries and families.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of an initiative to provide technical and educational assistance to North Carolina to develop an integrated care model for dual-eligible individuals and is supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation (LJAF). The authors would like to express gratitude for their generous support. The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.