Findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study suggest that 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life-years worldwide were attributable to dietary risk factors in 2017.1 The US Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and obesity as diet-related chronic health conditions.2

In 2021, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report on diet-related chronic health conditions and federal efforts to address them.3 The GAO reported that cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke), cancer, and diabetes accounted for 52% of all deaths in 2018. Furthermore, in that same year, spending for these diet-related chronic health conditions contributed about 25% of the $1.5 trillion in total health care spending.

Improving Americans’ eating behaviors could prevent or delay the onset of chronic health conditions, help patients manage these conditions, and prevent complications.4 Importantly, there is evidence that healthy eating patterns among US adults could save billions of dollars in annual health care spending.5

Family physicians are a potentially important source of credible information that can be instrumental in enhancing patients’ health through better dietary choices. The American Academy of Family Physicians established a nutrition curriculum guideline in 1989 that is updated regularly,6 and family medicine (FM) residency curricula are required to include training in behavioral medicine, which is a valuable adjunct to understanding dietary behavior change. In 2017, the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored a workshop to identify factors limiting progress in the implementation of nutrition training in medical education. In an overview of that workshop, it was suggested that “it may be best to direct initial [graduate medical education] GME training for nutrition dietary behavioral intervention and the treatment of obesity” to primary care specialties such as pediatrics, family medicine, and internal medicine.7 Arguably, family physicians are at the center of health care, and are often the first point of contact for patients seeking health care services.8

In the United States, approximately 25% of older non-institutionalized people are at risk for malnutrition. In the inpatient setting, that risk rises to as much as 50%.9 Malnutrition in the inpatient setting is associated with an increased risk of falls, infection, fractures, and pressure ulcers. The comorbidities in hospitalized patients create health care costs of $15.5 billion (about $48 per person in the United States) annually.10

Studies suggest that most physicians believe nutrition is important to health, although there is evidence that physicians continue to feel ill-prepared to provide their patients with nutrition guidance.11–13 Medical residency training may be an appropriate time to provide family physicians with the knowledge and skills necessary to address nutrition as a component of patient care.

This study investigated the current state of nutrition training in FM residency programs as well as residents’ attitudes and self-efficacy regarding nutrition. Our primary research question was, “What is the status of nutrition training in FM residency education in North Carolina?” A secondary question of interest was, “What are FM residents’ attitudes toward, and sense of self-efficacy for, nutrition counseling in primary care?”

Methods

Data Collection, Participants, and Setting

Using email addresses obtained from the American Academy of Family Physicians Database access system, the link to a 24-item online questionnaire was sent to 384 FM residents in February 2023 and again about 4 weeks later (Appendix A contains the questionnaire). Both residency program coordinators and directors were also emailed in February 2023 and 4 weeks later, asking them to encourage residents to complete the survey. Family medicine residents in post-graduate-year (PGY) 1–3 (expected graduation from 2023 through 2025) were included in this study, while residents in their post-graduate year greater than PGY3 were excluded. The Cone Health Institutional Review Board granted exemption status to this study.

Survey Instrument and Outcome Variables

An anonymous survey was used after obtaining written permission from the developer,13 who had adapted a validated 45-item questionnaire14 on resident attitudes regarding nutrition in patient care. The survey was modified to reduce length, to include history of nutrition training, and to include questions of self-assessed proficiency in specific areas of nutrition.

The first survey item gave a brief description of the research and informed participants that the submission of their survey indicated informed consent. Survey item 1 also provided contact information for the lead author and the Institutional Review Board if participants had any questions. The next 3 survey items consisted of categorical demographic variables, including current post-graduate year, gender, race, and ethnicity, and questions 5 and 6 determined background of formal or informal training in nutrition. Survey item 7 provided instructions for completing the questionnaire. Using a 5-point Likert scale, the remaining survey items assessed participants’ attitudes regarding nutrition in patient care (questions 8–16, 24, and 25) and their comfort level (self-efficacy) in providing nutrition assessments and counseling to their patients (questions 17–23).

Analysis

Analyses explored associations of formal or informal nutrition training with nutrition attitudes and self-efficacy. Crosstabulations were used to describe the nature and degree of associations. For most tables, chi-squared tests were used to calculate P values to assess statistical evidence of association. In cases where there were expected counts less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the P value. Statistical analyses were performed using R software,15 and a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

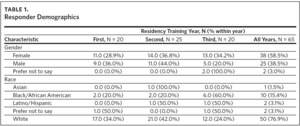

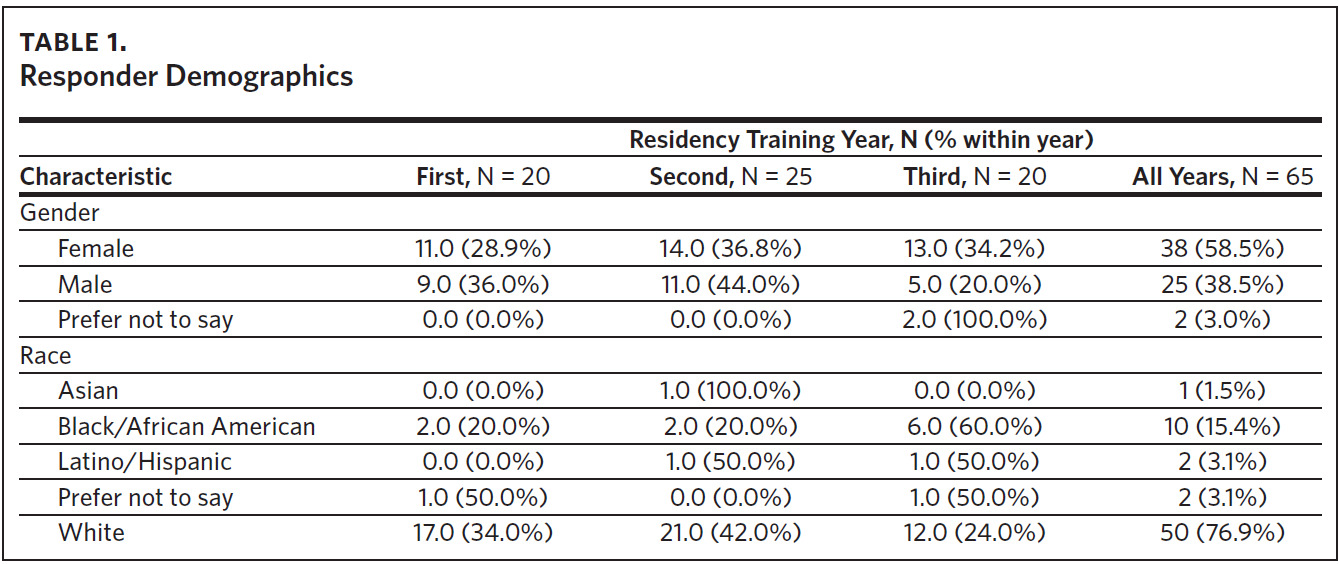

A total of 65 of 384 family medicine residents completed the survey, resulting in a 17% response rate. One responder failed to complete the last 4 survey items; analyses run with and without this participant’s replies yielded no statistically significant differences, so all available responses are included in the description of the results. Of the 65 responders, 38% (n = 25) were in their second year of residency training, while the first- and third-year residents each consisted of 31% (n = 20) of all responders (Table 1). Analysis of responses by PGY yielded no significant differences.

The majority, 59% (n = 38), of the responders were female, while 39% (n = 25) were male. The rest were either non-binary or preferred not to say. Among responders, 77% (n = 50) were White, 15% (n = 10) were Black, and the remaining were either Latino, Asian, American Indian, Pacific Islander, or preferred not to say (Table 1).

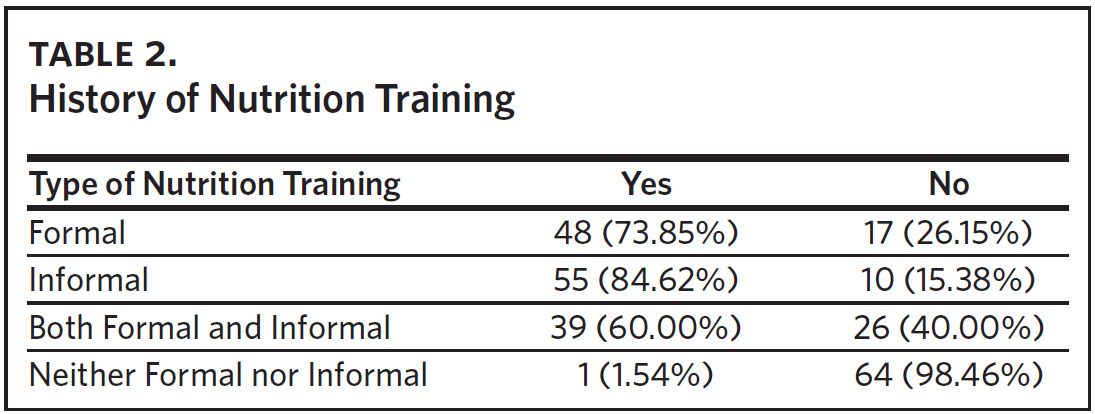

History of Nutrition Training

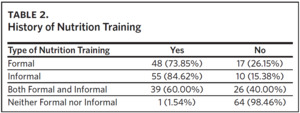

Ninety-nine percent of residents had received some kind of nutrition training, with only one resident reporting no nutrition training of any kind. Approximately 74% (n = 48) of all participants had received formal training (i.e., educational conferences, nutrition rotation or course) in nutrition, either in medical school or in residency. By comparison, about 85% (n = 55) had informal training (i.e., unstructured) during their medical education. A background of both formal and informal training in nutrition was reported by 60% (n = 39) of residents (Table 2).

A history of formal nutrition training was associated with greater agreement that physicians are not adequately trained to discuss nutrition issues with patients compared to those with no formal training: 88% (n = 42 of 48) versus 82% (n = 14 of 17), respectively (P = .023).

Informal nutrition training was associated with differences on 2 survey items. Of those with informal training, 51% (n = 28 of 55) reported feeling comfortable discussing dietary changes for patients with gastrointestinal (GI) problems versus 10% (n = 1 of 10) of those without informal training (P < .040); 93% of responders (n = 51 of 55) with informal nutrition training reported feeling comfortable discussing nutrition with patients regarding cardiovascular disease as compared to 90% (n = 9 of 10) with no informal training (P < .035).

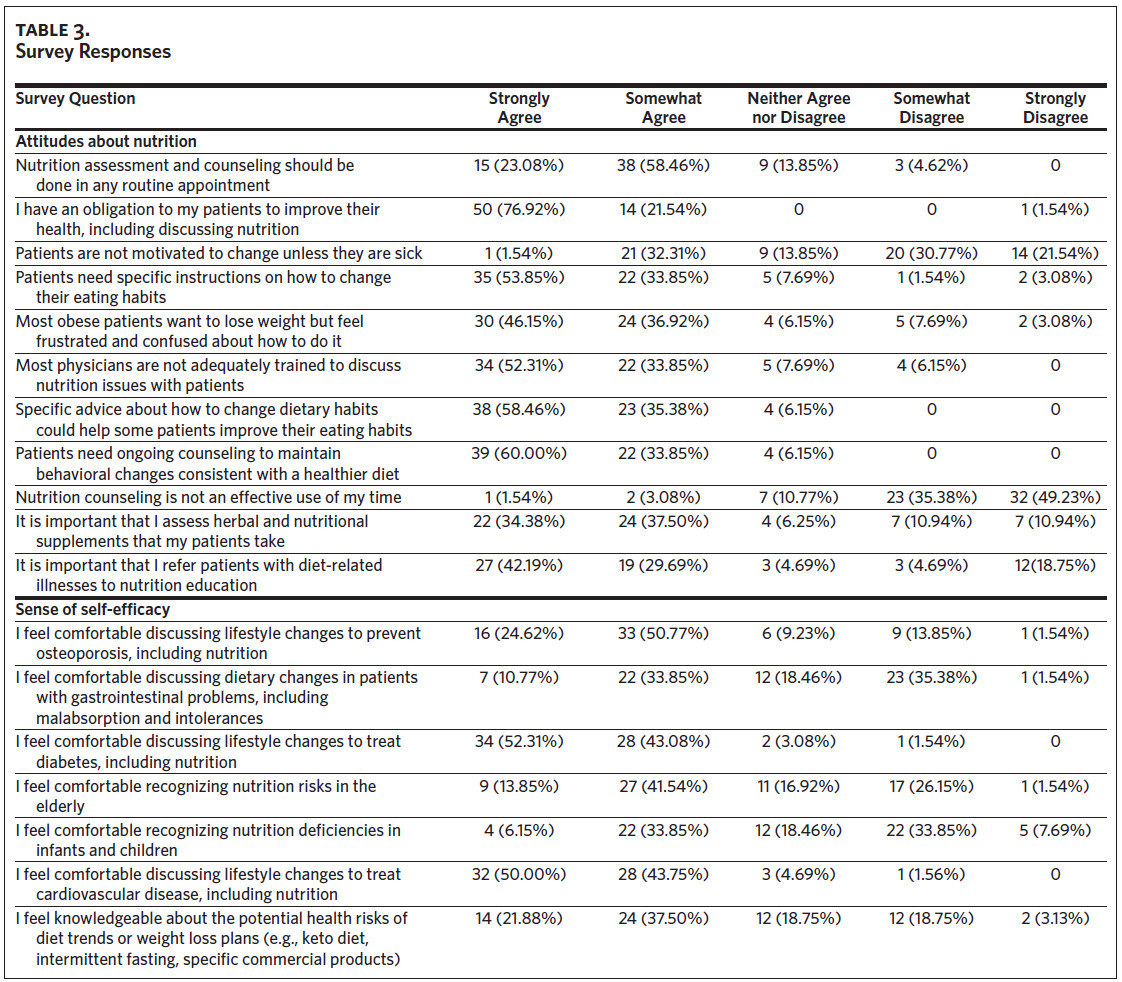

Attitudes About Nutrition

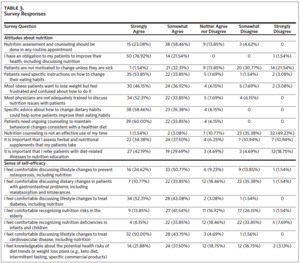

There was substantial agreement with respect to attitudes about nutrition: 99% (n = 64) agreed that they have an obligation to improve patients’ health, including discussing nutrition. There was 94% agreement (n = 61) that specific advice could help patients improve their eating habits and that patients need ongoing guidance to maintain dietary behavior changes. Eighty-eight percent (n = 57) agreed that patients need specific instructions on how to change eating habits, and 86% (n = 56) agreed that most physicians are not adequately trained to discuss nutrition issues with patients. Eighty-five percent (n = 55) disagreed that nutrition counseling is not an effective use of their time (Table 3).

Sense of Self-Efficacy

Most responders felt comfortable discussing lifestyle changes, including nutrition, to treat diabetes (95%; n = 62) or cardiovascular disease (94%; n = 61). Respondents did not, however, overwhelmingly express comfort treating specific subgroups of patients. Seventy-five percent of responders felt comfortable counseling patients about osteoporosis prevention, 10% were neutral, and 15% were not comfortable. Only 40% of residents agreed that they were comfortable recognizing nutrition deficiencies in the pediatric population, 18% were neutral, and 42% disagreed that they were comfortable. With respect to patients with GI disorders, 45% of respondents agreed that they were comfortable providing nutritional counseling, 18% were neutral, and 37% disagreed that they were comfortable (Table 3).

For the elderly population, 55% of respondents were comfortable recognizing nutritional risks, 17% were neutral, and 28% were not comfortable. Fifty-nine percent of respondents were comfortable discussing specific diets with elderly patients, while 19% were neutral, and 22% were not comfortable.

Discussion

A background of informal nutrition training was associated with increased resident confidence in counseling patients regarding both GI problems and cardiovascular disease. More than half (51%) of residents with informal training in nutrition reported feeling comfortable discussing dietary changes with patients with GI problems versus only 10% of those with no informal training. Likewise, with respect to feeling comfortable discussing nutrition aspects of cardiovascular disease, 55% of residents who had had some informal nutrition training strongly agreed they felt comfortable discussing nutrition for cardiovascular disease versus 20% of those with no background in informal nutrition training.

Formal nutrition training was associated with greater agreement that physicians are not adequately trained to discuss nutrition issues with patients versus among those with no formal training. This may suggest that their training increased awareness of the value of nutrition in medical care.

Among all residents, there was overwhelming agreement that specific and ongoing guidance can help patients maintain healthier diets, and that physicians have an obligation to help patients improve their health, including discussing nutrition. Eighty-two percent of residents agreed that nutrition assessment and counseling should be done in routine appointments.

In a study published in 2008, only 14% of internal medicine interns felt adequately trained to provide nutrition counseling, even though over 70% of them believed that nutrition assessment should be a part of routine primary care visits, and more than 90% felt obligated to discuss nutrition education with their patients.16 More recent studies confirm that primary care providers lack sufficient capability to provide nutrition care and counseling to their patients due to inadequate nutrition education during medical training.11–13,17–19

There is evidence of a discrepancy in physicians’ self-perceived nutrition knowledge and objective nutrition knowledge.20 Furthermore, there is variability in the amount and the extent of formal and informal nutrition training, and most medical schools do not meet the 37–44 hours of training recommended by the American Society of Clinical Nutrition.21 We know, however, that confidence in nutrition knowledge and the likelihood of providing nutrition counseling increases with nutrition training in medical school and residency.17,22 Despite the inverse correlation between good nutrition and chronic health problems such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, to mention but a few, nutrition education among physicians in training remains inadequate.11–13,16–19

Of note, most of the responders agreed that obese patients want to lose weight but feel frustrated and confused about how to do it, and that nutrition counseling should be an ongoing conversation with patients to maintain behavioral changes consistent with a healthier diet. Similarly, most of them (85%) believed nutrition counseling to be an effective use of physician time, which is in line with the perceived need for nutrition counseling to support healthy living. Inadequate nutrition education, however, may limit family medicine physicians from providing evidence-based nutrition education to prevent or treat chronic diseases, as seen in previous studies.16,17

A 2021 report showed that only 45% of accreditation and curriculum guidelines for medical education in 20 countries included any mention of nutrition.23 Citing evidence that accreditation systems have been shown to improve patient care,24,25 the authors recommend the incorporation of nutrition into accreditation frameworks, including undergraduate curricula, competency standards, and examination content for licensure.23

A report by the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic identifies opportunities likely to prompt an increase in nutrition education within medical education, including within undergraduate medical education (UME), graduate medical education (GME), step and board examinations, and continuing medical education (CME).26

Family medicine residency programs have the latitude to incorporate nutrition training into their curricula, as previously recommended by the current authors13,27 and others,28,29 without waiting for policy and accreditation changes to be mandated. For example, the inclusion of a registered dietitian/nutritionist (RDN) as a member of residency faculty provides a nutrition champion to teach both didactically and clinically. An RDN can teach the fundamentals of obtaining a diet history and providing dietary recommendations while modeling efficiency through the use of electronic medical record templates and a focus on the most common nutrition issues. In addition, a behavioral medicine specialist integrating principles of behavior change into the residency curriculum can promote residents’ effectiveness in guiding patients through lifestyle changes.

The aging demographics of the American population heighten concerns that medical education provides inadequate training in nutrition. Nutritional risk factors contribute to and exacerbate many aging-related health conditions such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and metabolic disorders, and malnutrition. Although legislation has been introduced to the United States Congress to broaden the diagnoses for which Medicare will cover seeing an RDN, currently the diagnoses are limited to diabetes and chronic kidney disease. This leaves primary care physicians as the sole providers of nutrition information in the health system. Equipping physicians with knowledge and tools to help reduce malnutrition alone could have meaningful benefits to both health care costs and outcomes. Shadowing an inpatient RDN even one time might help provide an appreciation for the health consequences of micro- and macronutrient deficiencies.

The current study included some limitations. First, using volunteer sampling for this study might have undermined the ability to have samples that are fully representative of the population being studied, thereby limiting the generalizations of the findings from the study to family medicine residents at large. Furthermore, it is not known if family medicine residents in North Carolina are representative of family medicine residents nationally.

Second, although the survey provided data on residents’ background in nutrition training, survey questions did not define “formal or informal” training. Indeed, all but one resident reported a background of formal or informal nutrition training, which is higher than previously observed.11–13,16,18 A better understanding of how residents interpreted “informal training” would be valuable in clarifying the role of nutrition education in resident attitudes and practices. In addition, the identification of the authors on the email request for study participation may have influenced the rate of reported history of nutrition training. A high response rate among responders from residency programs with which the authors are affiliated (n = 53), where both formal and informal nutrition training are provided, may have artificially inflated this variable.

The overall response rate of 17%, while typically considered low, was not surprising among the population sampled, however. FM residents have severe time constraints (work hour restrictions permit up to 80 hours per week). Expectations imposed on the residents often mean they work outside of their shifts, which rotate between night and daytime hours. FM residents are exposed to a vast number of surveys; those that are not required are seldom completed.

Historically, nutrition in medical school education is absent or is provided in biochemical terms (macro- and micronutrients) and very rarely provided after pre-clinical years. There is little to no culinary medicine teaching or education around food prescribing or food as medicine. These aspects of nutrition education have been shown to be efficacious.30,31 Further research should focus on developing a unified approach to nutrition education in US medical schools and the standardization of nutrition education in family medicine residency programs. This approach should be holistic and address social and cultural aspects of nutrition, involve participation in culinary medicine, focus on the impact of nutrition on population health, and simultaneously teach evidence-based tools to develop patient-centered assessments and plans.

Conclusion

This survey administered to FM residents in North Carolina suggests that residents feel their training in nutrition is inadequate, yet they feel that family medicine providers have an obligation to provide nutrition education to patients to improve health outcomes. Residents desire specific, evidence-based instructions for how to change patients’ eating habits.

In a time when we see government-supported research and initiatives to address food insecurity and nutritional quality of the American diet, numerous media reports and research on treatments for obesity, and centers of excellence created to promote food as medicine,32 we feel the education of North Carolina residents in the field of nutrition needs to improve. We must better engage our patients on the topic of nutrition. Nutrition should be a part of the patient-doctor relationship, similar to reviewing the patients’ vital signs. We have a duty to cut health care costs, and we have the tools to improve public health. We must get these tools into the hands of North Carolina medical residents. By dedicating more hours to practical nutrition teaching as recommended by the American Society of Clinical Nutrition, FM residents of North Carolina can feel more confident and empowered to serve their patients. In addition, medical organizations such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and their leadership can support integrating nutrition training into medical residency education by creating and funding competency-based nutrition training curricula.8

Acknowledgments

The authors have no financial disclosures or funding source to declare and no conflicts of interest to report.