Introduction

Beginning researchers over the past several decades have established adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as a critical public health problem impacting numerous health outcomes across the lifespan. ACEs refer to a variety of traumatic events and circumstances that children aged 0–17 experience, including abuse (verbal, physical, sexual), witnessing a death or abuse, living in a household with mental illness, substance use problems or an unstable household (parental separation, incarceration, etc.), or other community-related experiences (food insecurity, poverty, discrimination, etc.).1 Most data have indicated that roughly three in five US adults report experiencing at least one ACE during their childhood; further analysis has shown that more ACEs reported and accumulated is associated with increased risks for chronic health conditions or the clustering of conditions.2,3 These childhood experiences have been associated with increased risks for mental illness and substance use/misuse outcomes, smoking and obesity, cancer and cardiovascular diseases, and early death, among others, across the life course4,5; interestingly, this disease burden association also varies across geographic location due to potential differences in policies or support systems available.6 Further, these discrepancies in policies and support systems can exacerbate health disparities, particularly for historically marginalized populations.7,8 In sum, it has been estimated that the United States spends nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars annually to address the health burdens associated with ACEs, and cardiovascular disease is overwhelmingly the primary culprit due to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).4 DALYs measure the overall disease burden of populations and examine the loss of “healthy life” (inability to perform daily functions) due to the burden of a chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease.9,10 With this background, this paper seeks to provide an overview of risk factors for ACEs and mechanisms for cardiovascular disease stemming from ACES and the challenges and impacts for North Carolina specifically, and to present some potential opportunities to address ACEs and the intergenerational implications more effectively.

Adverse Childhood Experiences: Linkage to Cardiovascular Disease Across the Life Course

As with most public health challenges, it is best to take a life course approach to understanding the risk factors for ACEs and to further delineate why disparities exist.11 Life course approaches account for intergenerational exposures (physical, environmental, socioeconomic) that can impact human development biologically, behaviorally, and psychologically. Research over the past several years has illuminated the impact of historical trauma on epigenetic profiles, thus predisposing individuals to certain health risks.12 Therefore, when applied to ACEs, maternal health care and access to proper prenatal care can play a vital role; while limited research has been performed in this area as it relates directly to ACEs, evidence does suggest the care that mothers and their babies receive (or do not receive), both before birth and after, is essential to the proper development of a child.13 In addition, maternal (and paternal) ACEs are associated with an intergenerational risk for children; maternal mental health care, in particular, is critical.14 Next, early childhood care and educational development services are vital to children and their families. Without those, children will often lack the social support needed for proper social-emotional learning; in addition, the lack of care can exacerbate family and parental stress.15

Beyond the foundational first five years (ages 0–5), the community and surrounding environmental context becomes even more important as it pertains to risk factors for ACEs. This is very much rooted in the social and environmental determinants of health. The social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, housing, public education opportunities, environmental quality and physical infrastructure, and stress or discrimination, can serve as ACEs on their own; however, coupled with various forms of abuse, the traumatic experience can be amplified.16 In fact, recent critiques have argued that more attention needs to be directed at the social determinants or systemic drivers of health in order to prevent and reduce ACEs; in addition, tackling these root issues can help to break much of the intergenerational impacts.17–19

Lastly, it is important to mention the role of COVID-19 in creating new challenges for communities; it is likely that the pandemic led to further impacts on ACEs and has served as a traumatic event on its own.20,21 This may have been heightened in communities with fewer support resources and already vulnerable youth (i.e., LGBTQ, homeless). Further, parental burnout has been prevalent as people have been dealing with ongoing and evolving life difficulties related to the pandemic.

As it pertains to cardiovascular disease implications, there are two primary mechanisms by which ACEs can have the biggest influence: physiologically/biologically and behaviorally. First, much literature over the past several years has explored the role of chronic stress in health outcomes. Specifically, allostatic load, or physiological weathering, is the result of chronic stress and has been found to have significant impacts on the body’s physiological systems; this has implications for the development of such outcomes as cardiometabolic conditions (high blood pressure, diabetes) and increases the chances of chronic disease susceptibility in the longer term and across the lifespan.9,22 This relationship between ACEs and allostatic load can be mediated by the underlying social conditions (Figure 1). Next, ACEs have been associated with many of the health behaviors (smoking, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, alcohol/substance misuse) deemed as risk factors for outcomes including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol; each of these contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease.3–5 Furthermore, it is likely that the combination of allostatic load and behavioral patterns leads to the much greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease among those who have experienced ACEs and other traumatic events. Lastly, access to health care and clinical services as tertiary prevention is critical to managing chronic health conditions like cardiovascular disease. Research has found that those who have experienced ACEs are also much less likely to have adequate access to health care resources including health insurance as an adult, while having further needs for care.23,24

Challenges/Impacts on North Carolina

There are numerous challenges to addressing ACEs in North Carolina. Recent reports have found that approximately 60% of North Carolina adults acknowledge at least one ACE; even more concerningly, more than one-third had two or more ACEs.25,26 When exploring the data more closely, there are vast health-related disparities (i.e., rural/ urban, regional) found across the state associated with ACEs; those adults reporting ACEs were more likely to have children in their home (intergenerational risks), and the data used were from before the global COVID-19 pandemic, which likely has exacerbated these impacts. When related to direct cardiovascular disease risks, four or more ACEs were associated with increased risks for smoking, heavy alcohol use, obesity, and food insecurity.25,26

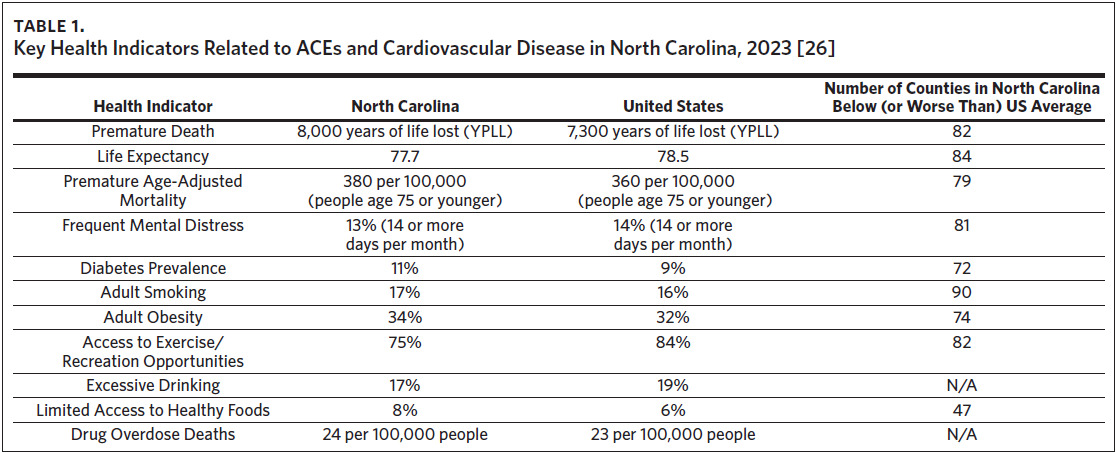

North Carolinians have a higher prevalence of diabetes, adult smoking, adult obesity, and limited access to healthy foods than the average numbers across the nation.27 Additionally, citizens report decreased access to exercise and recreation opportunities and the state has a slightly higher drug overdose death rate when compared to national averages. Within the state, more than 70 counties have increased rates of diabetes, adult smoking, and obesity, and limited access to exercise and recreation opportunities; many of these counties are rural and encounter numerous social and economic challenges concurrently (Table 1).

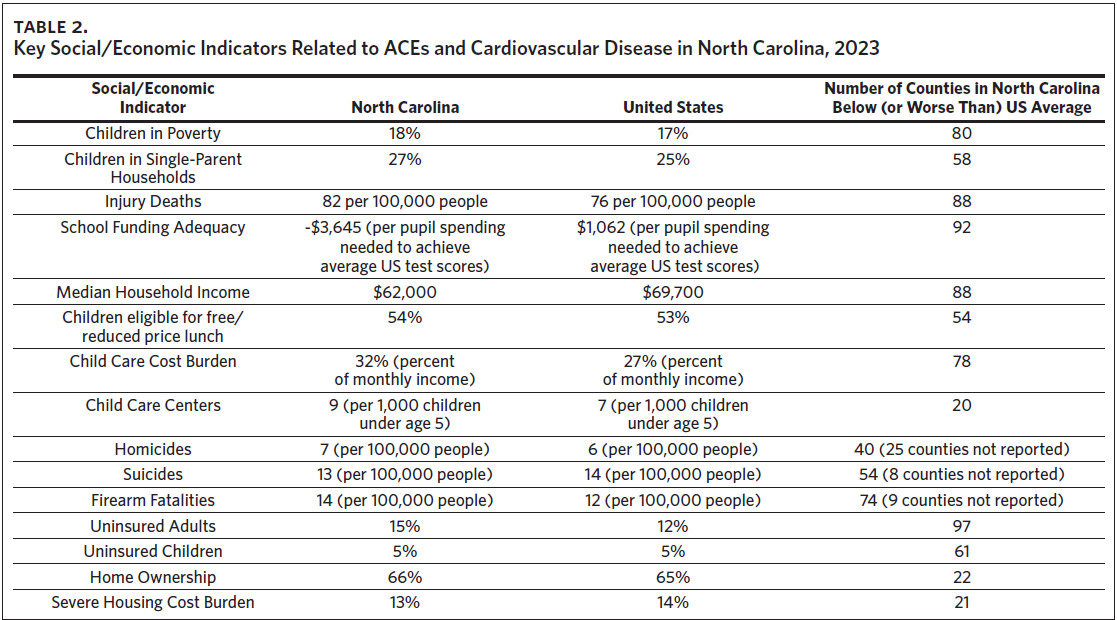

Regarding the root causes of both ACEs and cardiovascular disease outcomes, the state currently has challenges related to children in poverty as well as households with single parents. Disturbingly, the state has fallen way behind in recent years as it pertains to funding schools adequately27; this can lead to further limitations in the support needed for students that is often not found at home. Another area of critical concern is the excessive cost of child care and housing; interestingly, North Carolina is near the average nationally when it comes to housing cost burden, but there are some pockets of the state where housing has become a major challenge (i.e., Watauga County has a 21% housing cost burden rate, and the Eastern and Western regions of the state are much more rural and face unique challenges).27 The housing cost burden is a measure of the “percentage of households that spend 50% or more of their household income on housing”.27 Lastly, the state must address health insurance and health care costs; it is timely that North Carolina recently became the 41st state to adopt Medicaid expansion. Hopefully, this will lead to expanded opportunities for lower-income families who lack coverage and to alleviate some health disparities related to income and health care coverage.28

Opportunities and Potential Policy Solutions: Look Upstream and with a Life Course Approach

Too frequently, we examine health and social challenges independently and fail to incorporate a systems framework to understanding and addressing critical public and population health outcomes, such as how to reduce ACEs, thereby positively impacting cardiovascular disease outcomes over time. More commonly, the approach is to deal with the immediate and short-term treatment of disease in individual patients rather than taking a comprehensive multi-sector and population-based strategy. The public health framework urges us to go upstream and seek prevention mechanisms at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. As public health advocates, we must first reject the notion that bad parenting and individual-level factors are the major causes and educate the public more effectively about the root historical, structural, and social (primary-level) drivers of ACEs.29 Only then can we have substantive and sustained positive impacts.

Fortunately, there are some promising frameworks and resources available when seeking to address population-level risks for ACEs and the downstream influences on cardiovascular disease outcomes. At a state level, Washington State has been at the forefront of efforts aimed at reducing ACEs. Specifically, the state has worked to create a common language for people to understand the ramifications of ACEs and leaders have pulled together a diverse group of stakeholders (public, private) to work together on this initiative. In addition, state legislators have used ACEs data to inform policies related to prevention activities and passed legislation (HB 1965, 2011) to support efforts aimed at the primary prevention and root causes.30 California, through the Office of Surgeon General Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, is worth emulating, as it is using a comprehensive approach centered around health equity and systemic reforms.31

At the community level and relevant for diverse communities across North Carolina, there are further comprehensive frameworks that can inform action. The Center for Community Resilience at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health has provided much assistance to communities, both rural and urban.32 This includes a partnership with AppHealthCare, the local health department serving Watauga County, where the approach centers on a prevention model aimed at connecting the dots between community environments and the resulting ACEs impacts on individuals and families. AppHealthCare also focuses on addressing root causes (i.e., poverty, housing, economic mobility and opportunity, social capital) at the policy and systems levels. School leaders in Watauga County have adopted a Compassionate Schools approach, and multiple stakeholder agencies have partnered to form the Watauga Compassionate Community Initiative (WCCI).33,34 This group includes school officials, public health and social service agencies, political leaders and government officials, early childhood and other nonprofit agencies, and medical professionals working together to advocate for the community and to inform policies and practices (universal home visitation, family-friendly work policies, housing, etc.) aimed at reducing ACEs and assisting families in need. Above all, these efforts must be built for sustainability and impacts that can, over time, have significant decreases in cardiovascular disease outcomes.

Conclusion

Adverse childhood experiences are no doubt a pressing public health and societal issue of our time. It will take sustained efforts by public health and medical professionals, as well as political leaders, over time to incrementally make necessary reforms. Many of the issues involved are deeply rooted in historical trauma and systemic oppression, and until we address those, outcomes will not change dramatically. However, the evidence is clear: if we want to improve public health outcomes (i.e., improved quality of life, lower health care costs, increased productivity) for conditions such as cardiovascular disease, we must address the root social determinants of health. At the end of the day, the choice is ours: what kind of society do we want to provide for future generations? Our policies and practices should reflect the answer.

Acknowledgments

The author reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

_and_cardiovascular_disease.png)

_and_cardiovascular_disease.png)